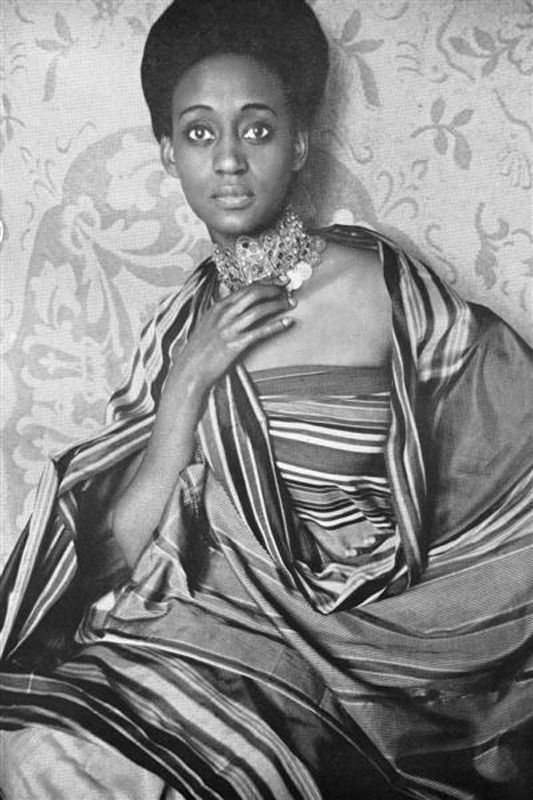

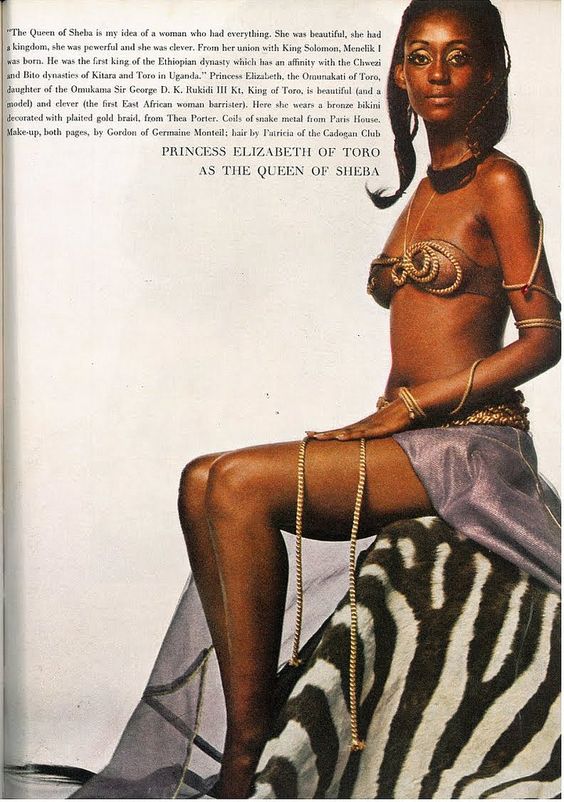

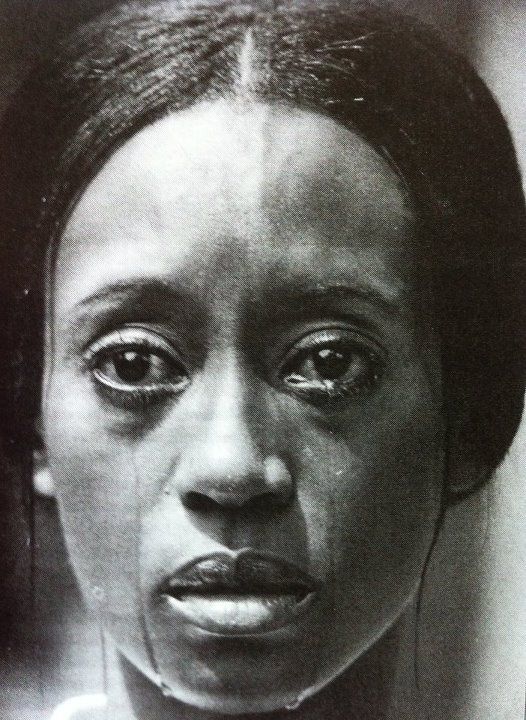

Today, we’re formally inviting you to shift your gaze to a lesser-known royal, deserving of her own spotlight: Elizabeth of Toro, the Ugandan Princess, lawyer, actor, top model, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Ambassador to the US, Germany and the Vatican in the 1960s. Her life reads like a trophy wall, and that’s only half of it. The Cambridge graduate was the first female East African to be admitted to the English Bar and later worked for, then escaped, Ugandan dictator, Idi Amin. She’s survived a brutal regimes, periods of exile and prejudice, and simply just isn’t you run-of-the-mill maiden. She’s our Vintage Muse du Jour…

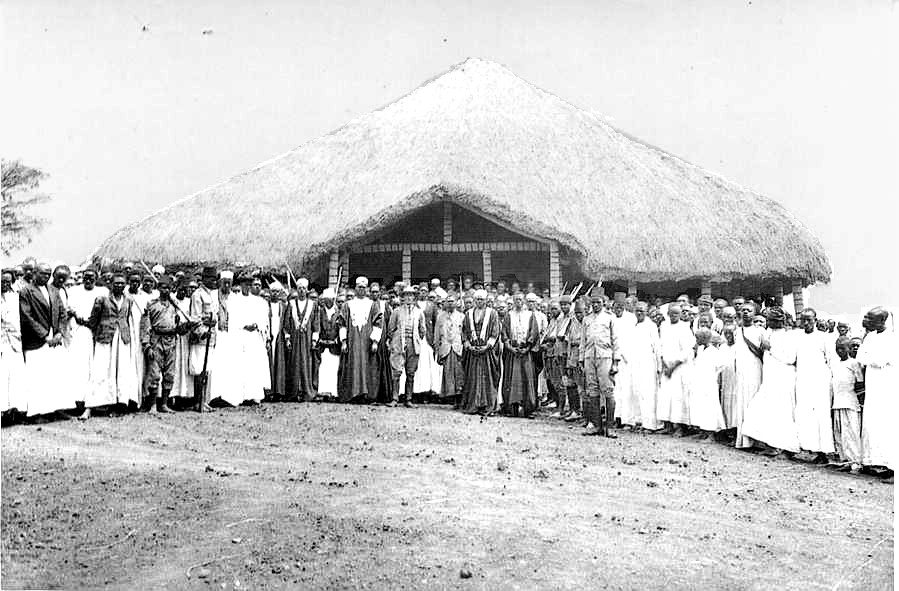

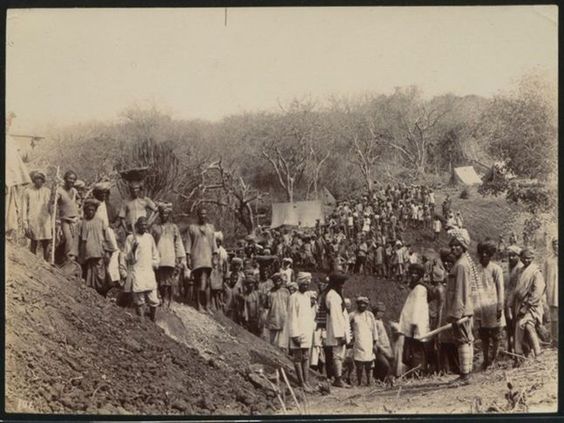

She was born Elizabeth Christobel Edith Bagaaya Akiiki of Toro in 1936, a princess in one of the five, 15th century-old kingdoms on the Ugandan border. The kingdom, which is actually called, “Tooro,” was affiliated with ancient Egyptian rule and practices; subjects buried their royals in the same way one would an Egyptian Pharaoh.

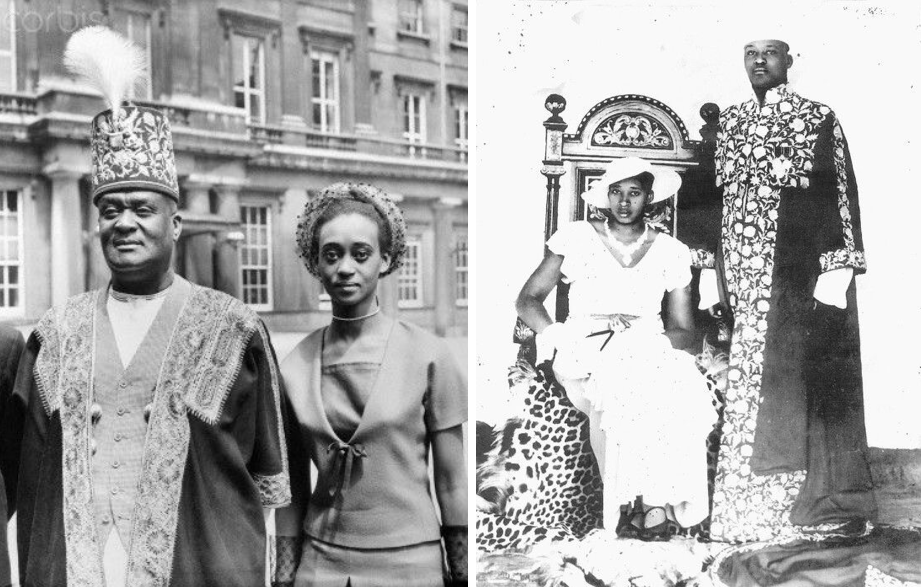

Here she is with her father (left image), George Rukidi, the “Omukama” or King. On the right is her mother, Queen Kezia, yet another woman of staunch character and chief advisor to her husband.

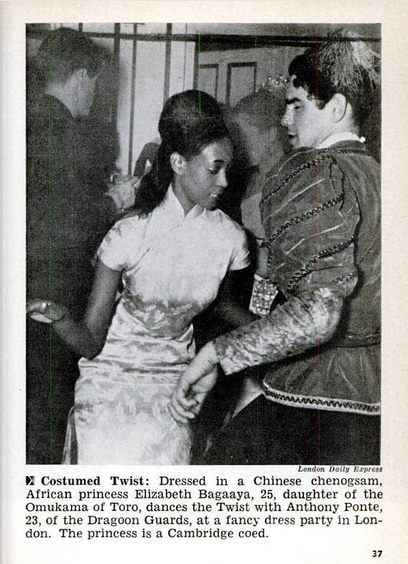

Tooro was still under rule of the British Empire — a reality that was a real two-sided coin for the Princess. On the one hand, Elizabeth had access to an excellent education; on the other, she felt as if she had to consistently prove herself to those in the upper crust schools. “I felt that I was on trial,” she later said, “and that my failure to excel would reflect badly on the entire black race.” One year later, she was admitted to the prestigious University of Cambridge to study law.

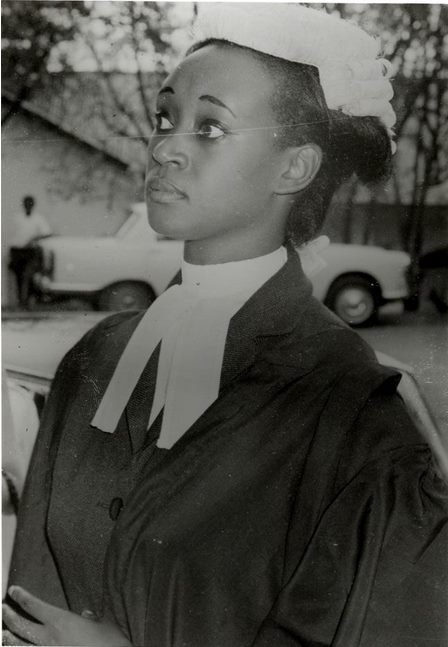

It would be the start of a long career for Elizabeth, who was the first East African woman to be admitted to the English bar and went on to have an illustrious career in politics within, and outside of, her own kingdom.

Once her father passed away, she explained in her autobiography, “I was the chief adviser to my brother, the King of Toro.” It was her word, in a way, that most resonated in the King’s ear…

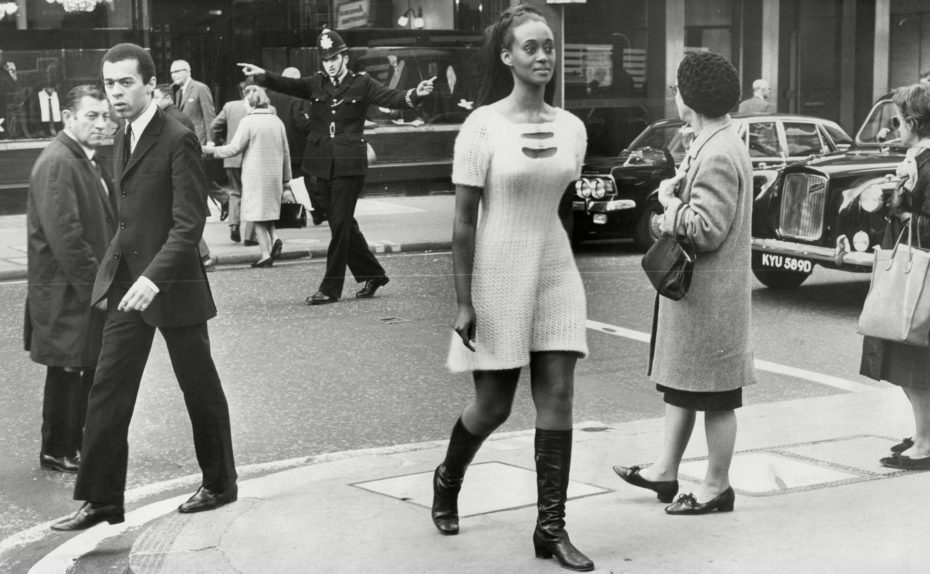

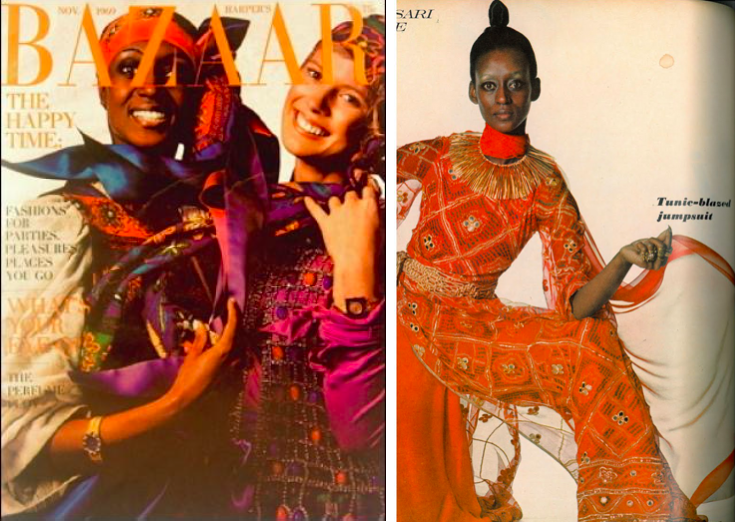

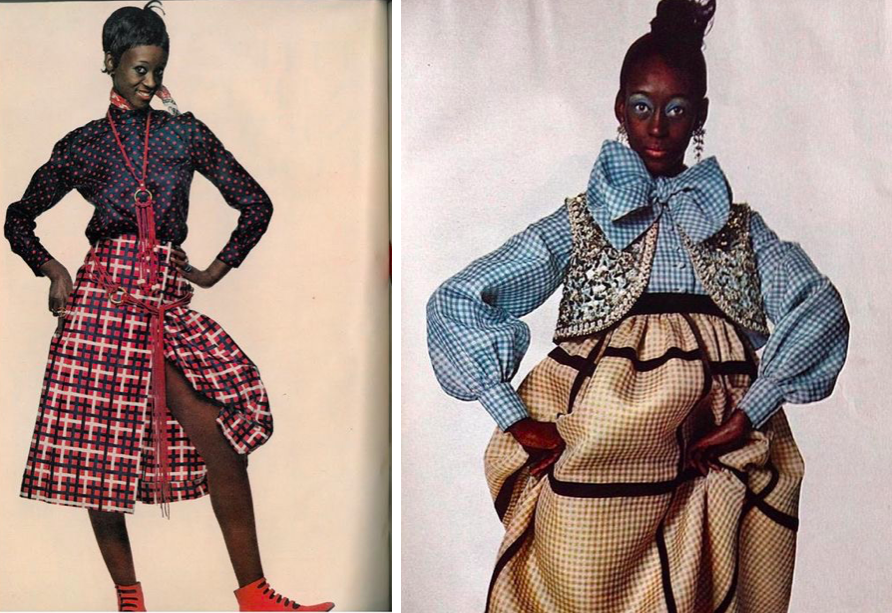

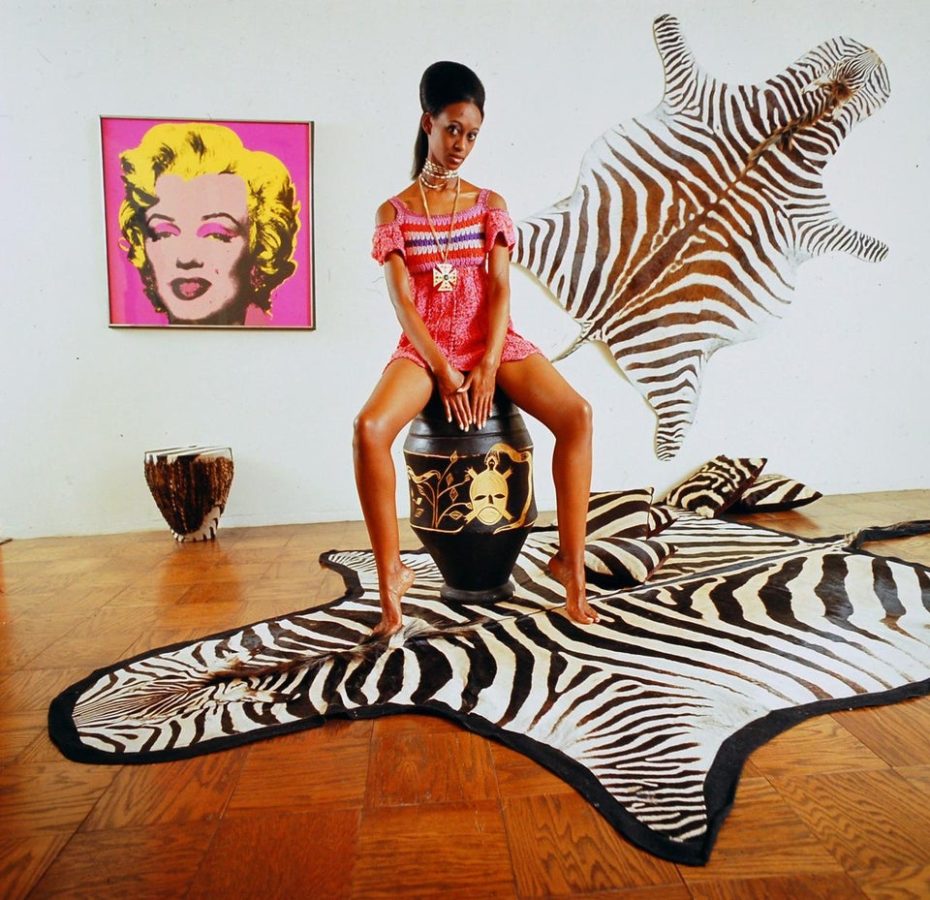

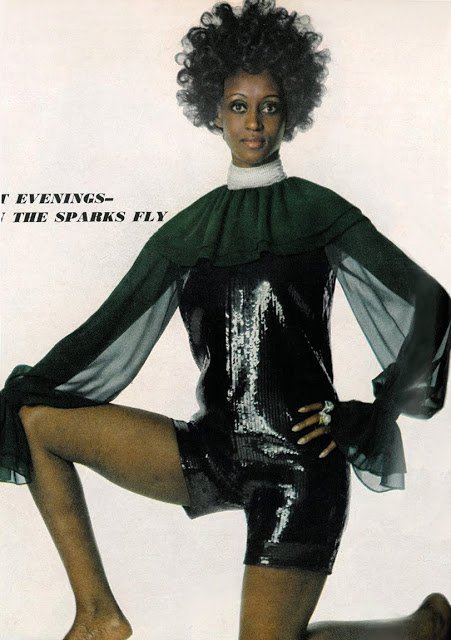

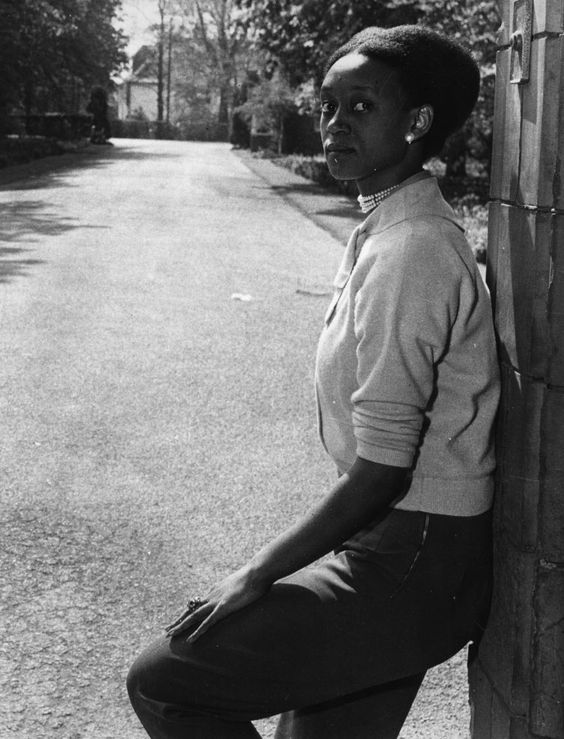

It was also a very tumultuous period for Tooro, whose monarchy was abolished in 1967 and wouldn’t be reinstated until the early ’90s. It was Princess Margaret, a friend of the Ugandan Princess, who jumped in to effectively save her from becoming a prisoner in her own land. Margaret, being the coolest one in the Royal Family (let’s be honest) flew her in for a fashion show in London in a gesture of solidarity, and a nudge towards another fun past-time for the Princess: high fashion.

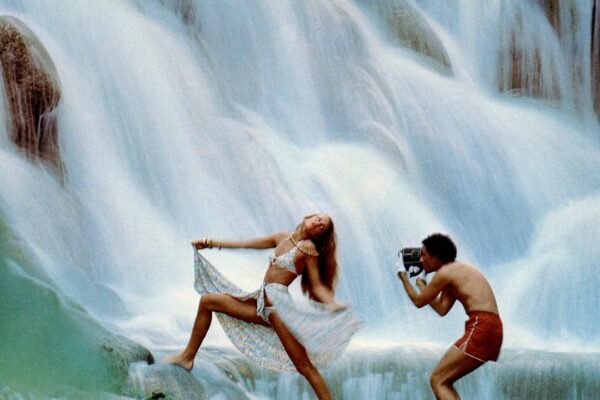

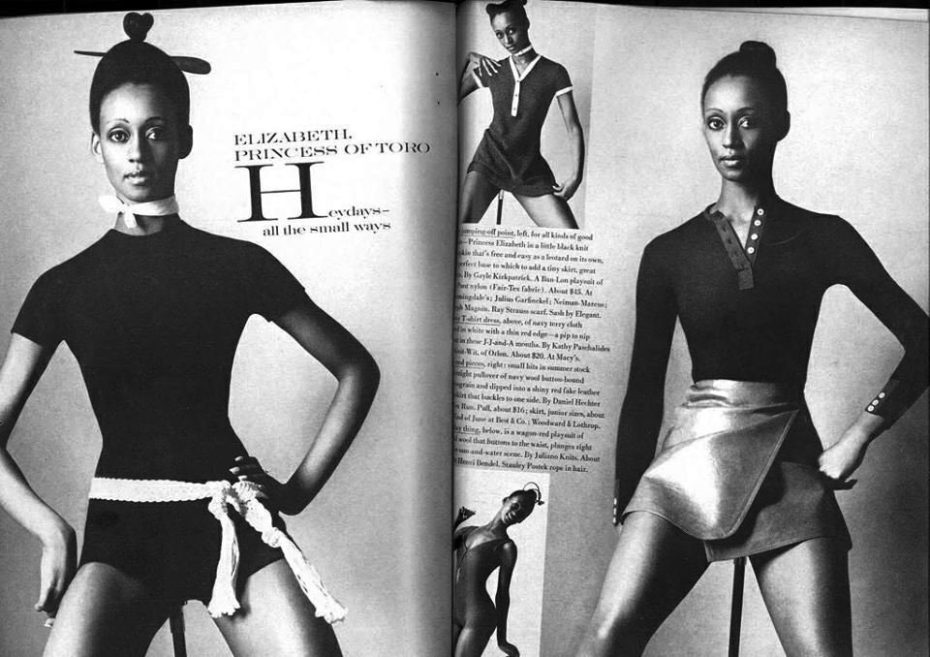

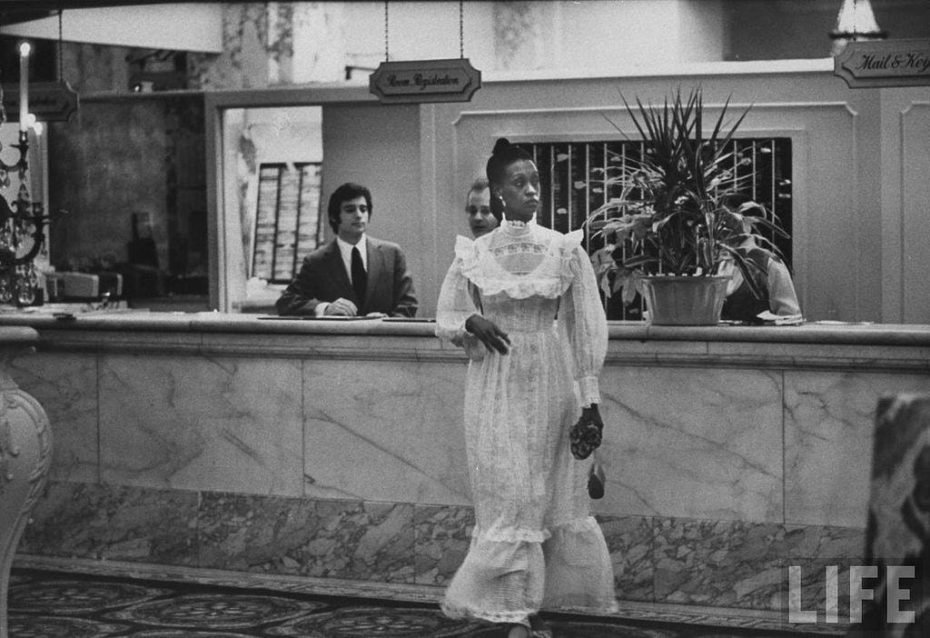

Elizabeth was instant hit, and even caught the eye of Jackie Kennedy Onassis, who convinced her to move to move to New York for a spill.

“I was featured in American Vogue, LIFE and Ebony and I was the first Black to appear on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar,” she wrote, “I have always been a symbol of what a black person can be in any field.”

She also starred in the film adaptation of author Chinua Achebe’s classics, Things Fall Apart and No Longer at Ease. The movie was “based on igboland, a region of eastern Nigeria,” explained Elizabeth, and “meant to expose the impact of Western civilisation on Africa.” She was on top of the world — but her homeland was at its own political boiling point.

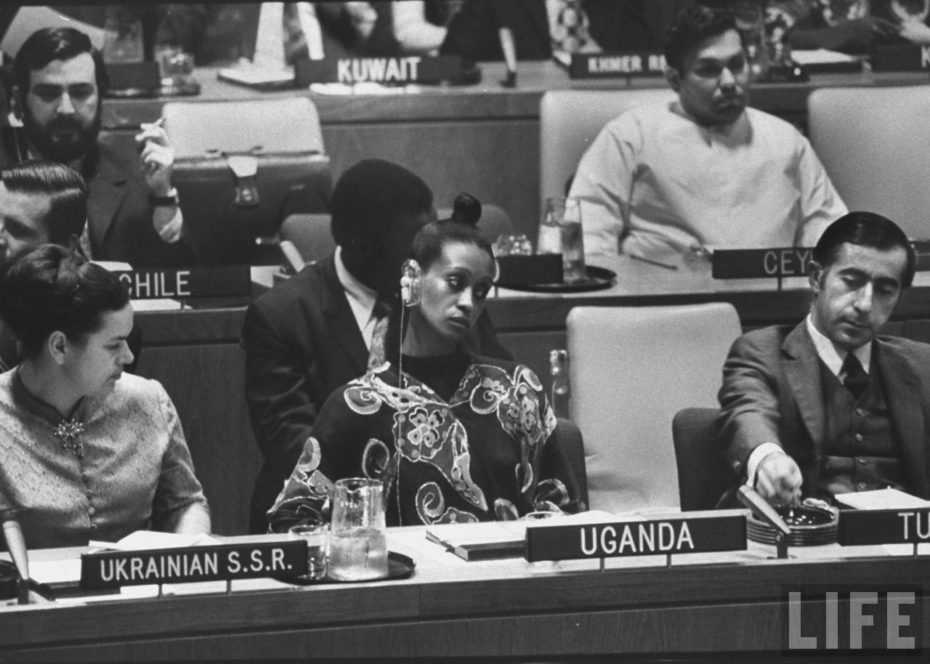

By the 1970s, the late dictator Idi Amin, “The Hitler of Africa,” had taken complete control of the country. He demanded that all Ugandans with Asian ancestry (about 60,000 people) leave their homeland in 90s days, ruling through violence, greed, and above all, instilling fear in his citizens. He offered Elizabeth a position as Minister of Foreign affairs, and let’s just say that when a dictator ‘offers’ you a role…well, you can’t really refuse. It was a harrowing period in the Princess’ life, and one that demanded a serious blend of smarts and social tact. It was a question of survival, but when she refused to marry Amin, she was fired.

“Some people who had been eyeing my post told Idi Amin that I was plotting to over-throw him,” she wrote, “and he had me placed under house arrest. But for international and local pressure, I would have been killed. I managed to flee into exile, only to return to Uganda in 1980.”

To this day, she remains an icon and inspiration to her people — but her story is still overlooked. “I wish to see Africa working towards the achievement of a real and authentic African identity,” she wrote about her work in politics, “as well as developing ways to ensure that our cultures and values are well promoted and protected. There should be a proper knowledge and documentation of our history, tradition and art, through which other people could learn and appreciate our concept of living.” Now that’s the kind of majesty that doesn’t need a title.