Something else they forgot to tell us about in history class: Black Wall Street. Why is it that our textbooks neglected to tell us about the African Americans who opened their own banks, did business with the Rockefellers and prospered as entrepreneurs decades before the Civil Rights Movement?

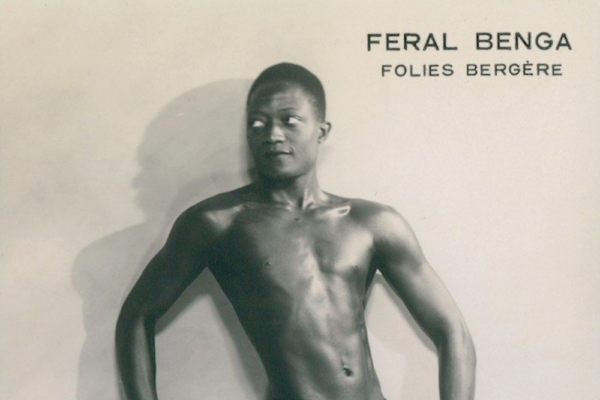

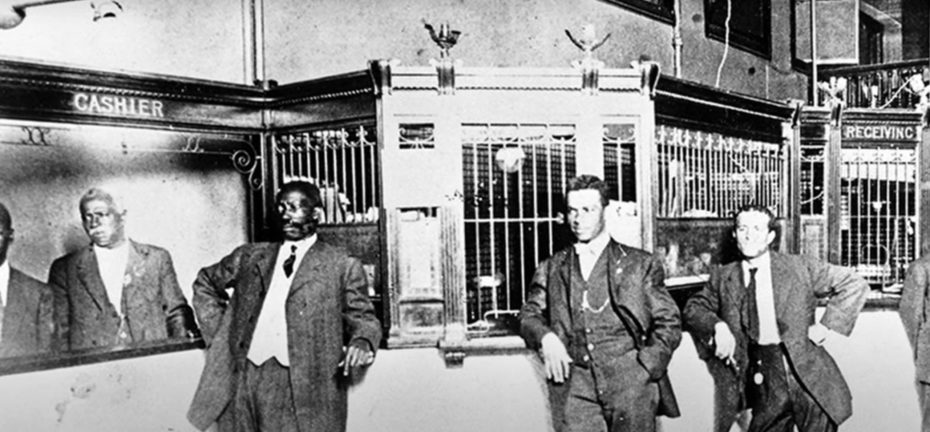

Yes indeed, long before desegregation, America had a black middle class that was thriving alongside pockets of the white elite. If you look hard enough, you can dig up historical photographs of African Americans dressed in tuxedos and top hats, driving high society cars and running busy financial offices. They are images that are all too unfamiliar, seemingly presenting an alternate version of black history far removed from the Jim Crow horror stories and civil rights struggle we’ve always been shown. But for a brief window in history there, Black Wall Street was headed for a very interesting future…

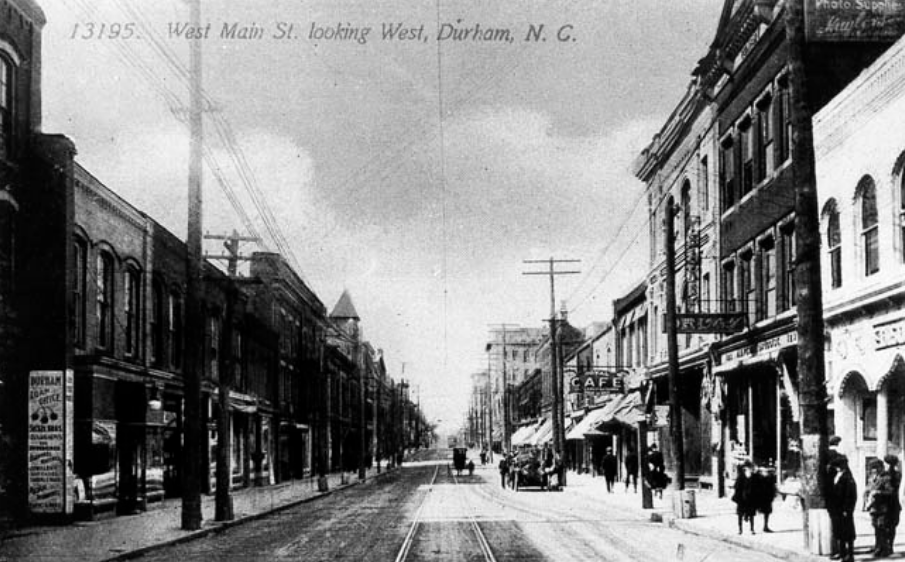

Durham, NC, Richmond, VA and Tulsa, OK; these are the three American cities at the centre of this story. Together, they blossomed into what became known nationally as “Black Wall Street,” a turn of the century trifecta of African American economic success, from the smallest of mom-and-pop-shop owners to bankers and oil barons. Commerce that was owned by, run for, and benefitting of black communities were precious but growing anomalies in post-Civil War, Jim Crow America. And Black Wall Street was at the epicentre of it all…

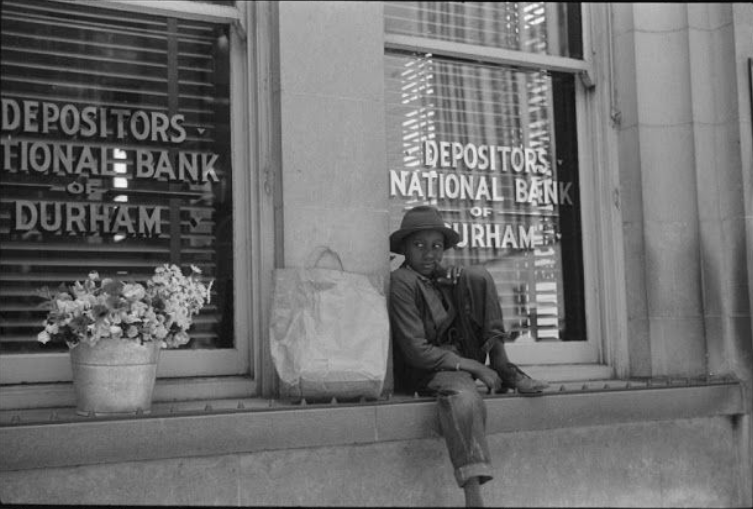

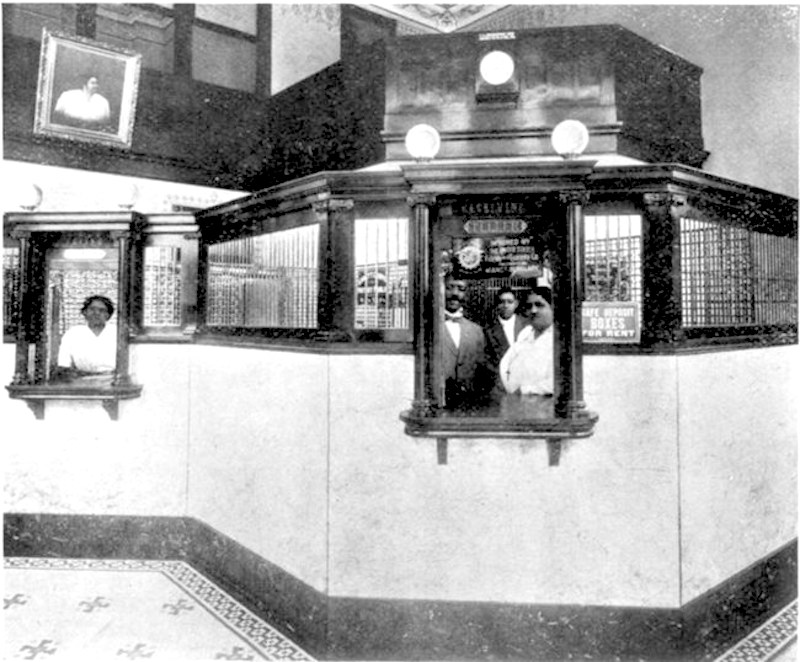

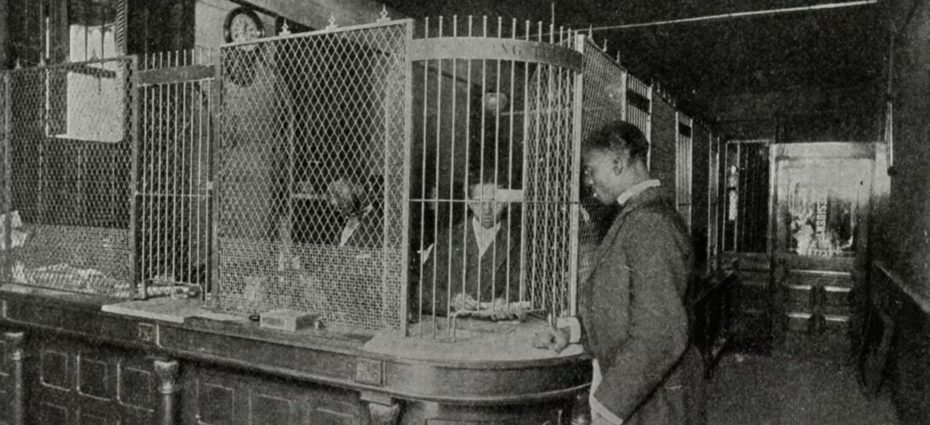

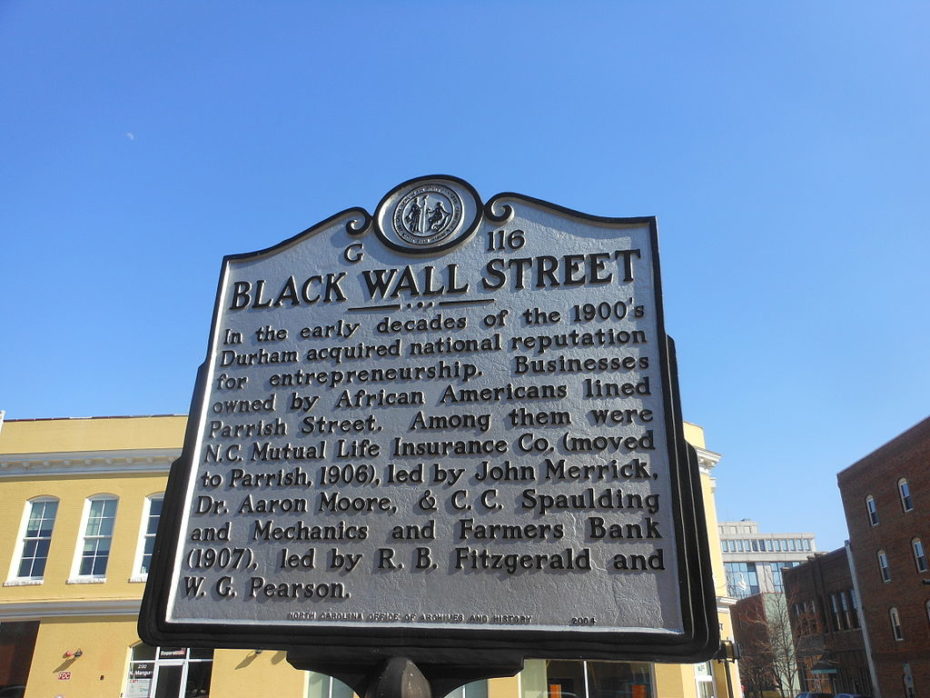

The very first African American Bank was founded in Durham, NC, also home to North Carolina Mutual insurance, which to this day, remains the largest and oldest African American life insurance company. Durham’s Perrish Street was like the Champs Elysées of black business owners, truly becoming the world’s epicentre for black finance.

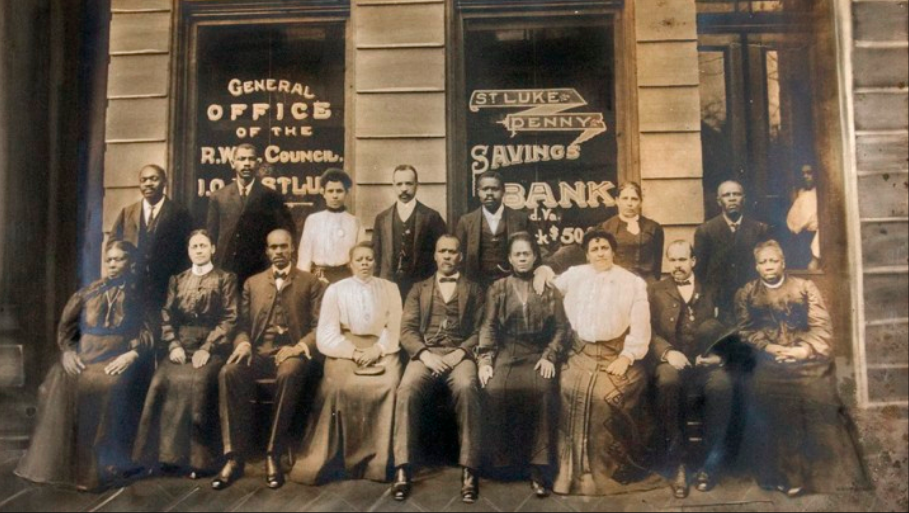

Over in Richmond, Virginia, whose Jackson Ward neighbourhood had a booming business and entertainment scene, the first ever bank to be chartered by a black woman in America, opened in 1903 by Maggie Walker. St. Luke Penny Savings Bank survives to this day, the oldest continuously operated African-American-owned bank in the United States.

Walker’s bank had something so few banks do: real, honest to goodness heart. “Let us put our money out at usury among ourselves, and reap the benefit ourselves,” she’s quoted as saying, “Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

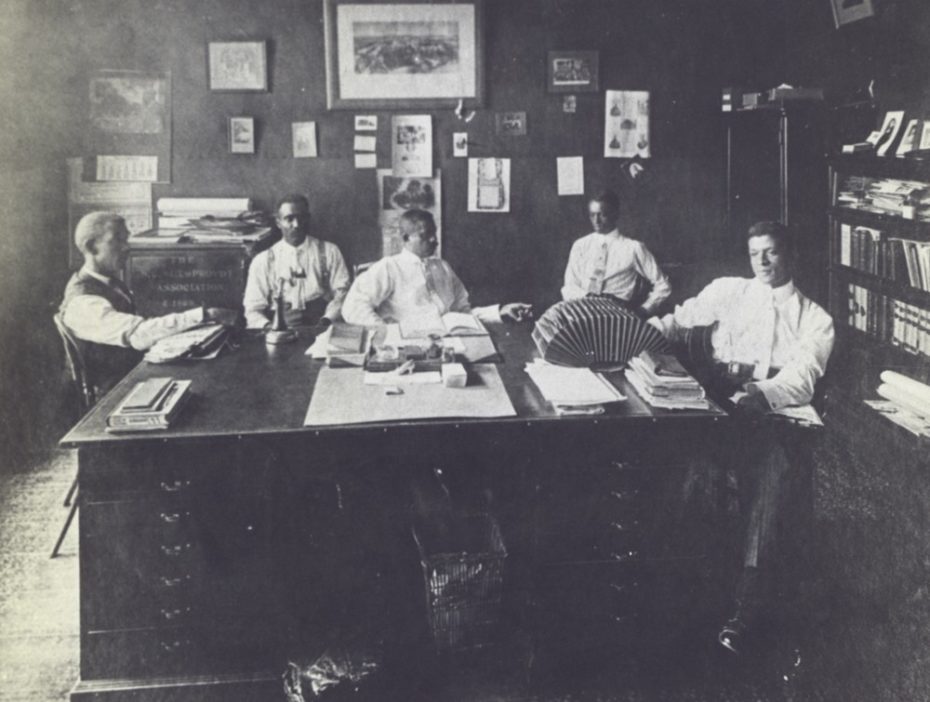

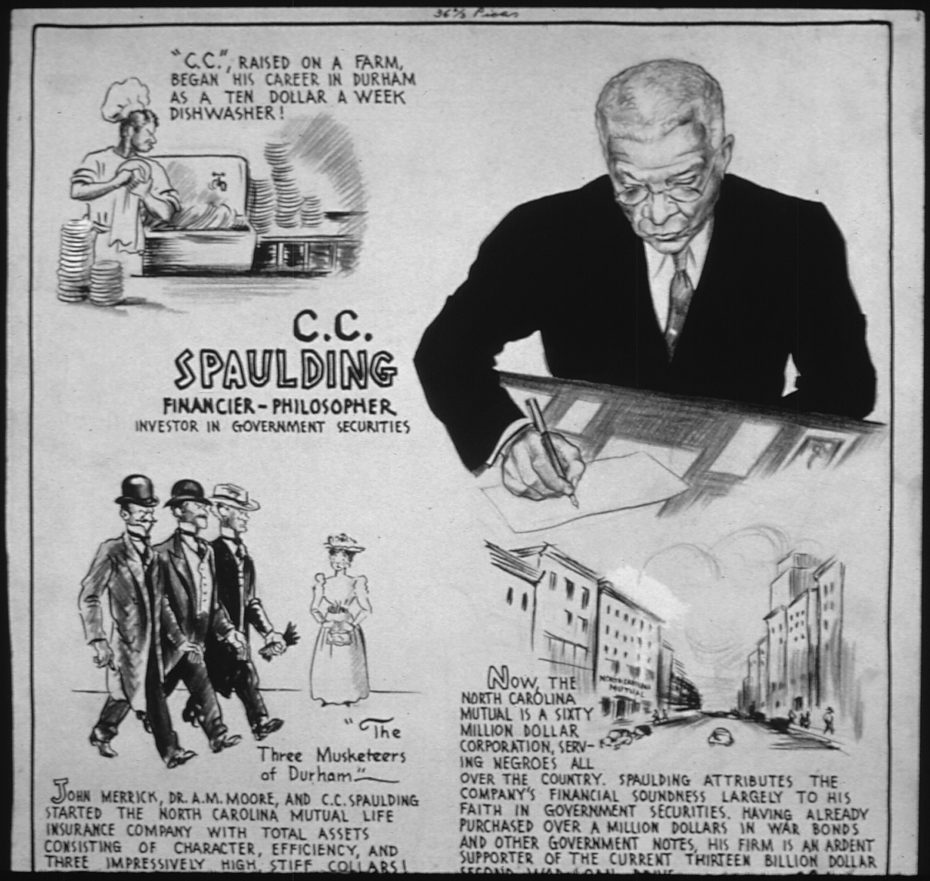

Further into the heart of the Deep South, Durham’s overall business savvy can be largely traced back to the efforts of two African American entrepreneurs: John Merrick and Charles Spaulding. Merrick was actually born into slavery, making his success not only a story of wits and grit, but heroism. He learned how to read in a Reconstructionist school, and prospered in the barbershop business before eventually breaking into insurance with North Carolina Mutual.

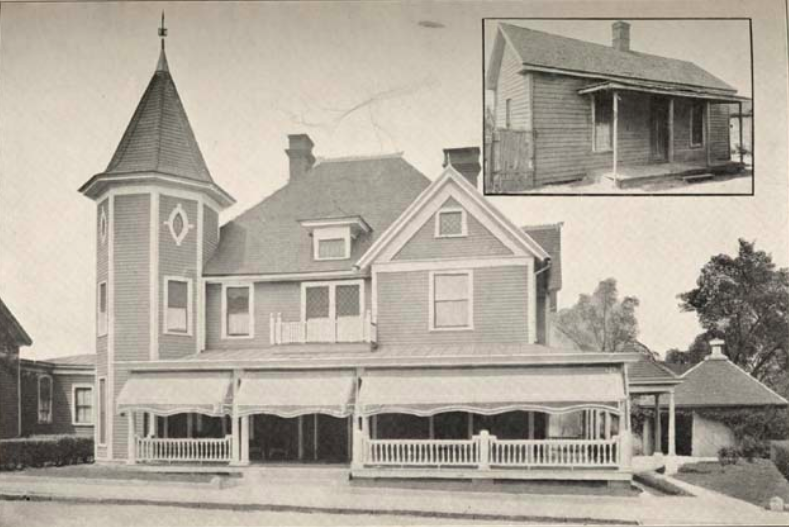

Eventually, he sold it for $4,986,344.40, making him one of the world’s most successful black entrepreneurs to this day. At a time when black home-ownership was a complete anomaly, his digs weren’t half bad either, especially impressive when juxtaposed with a snapshot of his very first house:

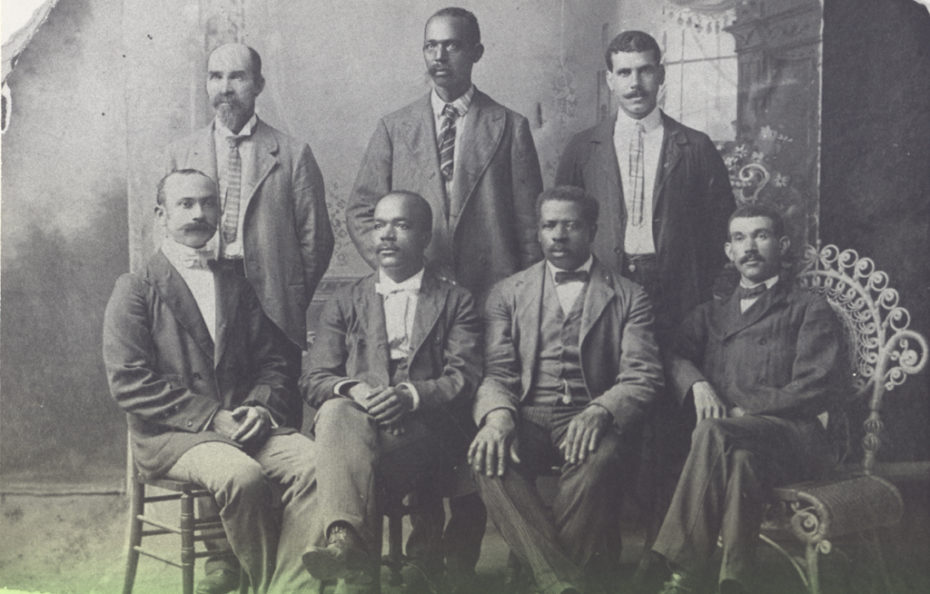

Merrick and Spaulding were often heralded as the epitome of Booker T. Washington’s “black captains of industry.” Durham’s wealth depended on important figures in the African American community like Booker T. Washington to engage with the white elite.

Philanthropists and entrepreneurs like Andrew Carnegie, William Howard Taft, George Eastman and John D. Rockefeller himself, who all became prominent investors in African American businesses and educational programs.

Black schools, for example, received little funding from the local government and such large investment in black enterprises, particularly from white individuals, was very unusual for this time in the south.

That’s not to say the wealth was equally distributed, particularly Durham’s poorer community of Hayti. Nor was it entirely possible without select white benefactors, and more ironically, without segregation…

Before integration, in cities like Durham, the only place that an African American could bank with was the black-owned bank that was providing loans and boosting black businesses. With the Civil Rights Movement, white-owned banks were forced to desegregate and the money that once flowed into black banks ended up on the white Wall Street. The money travelled further away from the communities, and once the gates of integration were open in America, black wealth began to hemorrhage, fast.

“We started to lose a lot of our businesses and support for our businesses,” president of the National Bankers Association, Michael Grant, told The Atlantic. “That was the toxic side of integration.”

Our final stop is in Tulsa, and it’s bittersweet. During the oil boom of the 1910s, the area of northeast Oklahoma around Tulsa is flourishing. Its Greenwood neighbourhood is a place of limitless opportunities, where the dance halls run all-night, black-owned boutiques are opening up and down the main thoroughfares and a high rate of black home ownership sets it apart from other American towns. Segregation has created a need for black individuals to produce and supply the goods they aren’t allowed to buy over on the white side of town. The result is a self-sufficient economy for the suburb, making the most of the divide to help Greenwood small businesses grow.

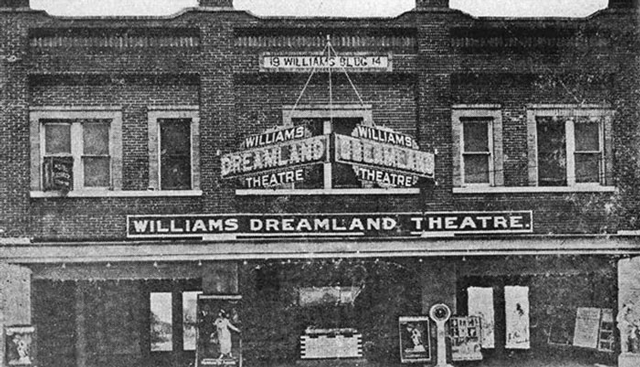

Here’s a shot of John Wesley Williams and his wife, Loula Cotten Williams. “John was an engineer for Thompson Ice Cream Company,” says the Tulsa Historical Society, and “Loula was a teacher in Fisher. The family was the owner of Dreamland Theatre”:

By 1921, the Greenwood neighbourhood, had came to be known locally as “the Negro Wall Street” (now referred to as “the Black Wall Street”). The buildings on Greenwood Avenue housed the offices of almost all of Tulsa’s black lawyers, realtors, doctors, journalists and other professionals. Records at this time count approximately 600 black-owned businesses, 30 grocery shops, two movie theatres, six private airplanes, a bank, a hospital, and a school system.

Then, in the span of a night and a day, that all changed one Spring in 1921 with the Tulsa Race Riot.

It began with the arrest of a young black man, who was temporarily arrested for the believed assault of a white elevator operator named Sarah Page while on duty. Today, most evidence leans towards a case in which Rowland simply tripped over Page while in the elevator. Regardless, something wicked was unclenched that day in Tulsa.

The unfurling of the Riot — which was really more of a massacre, as the word ‘riot’ implies a more level playing-field between opposing parties — reads like a textbook case of racist, sheeple hysteria. First, the white-owned Tulsa Tribune broke the story. That led to mobs congregating in front of the Court House were Rowland was held, which led to a crowd of about 75 black citizens (many WWI veterans) coming to protect Rowland. Soon there were thousands of furious whites before them.

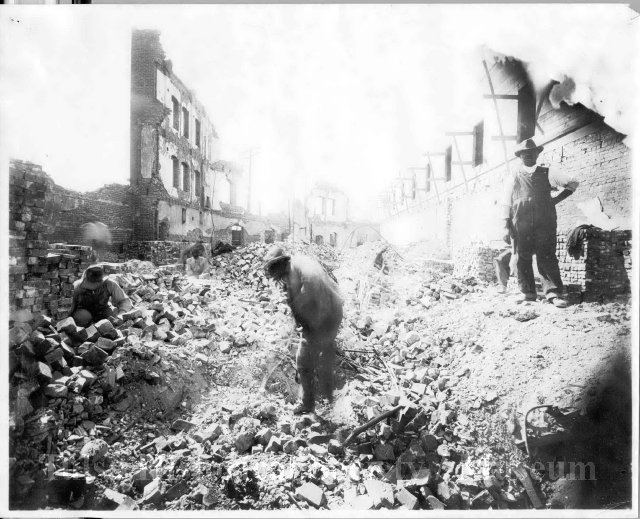

By 11pm, the Oklahoma National Guard was called in to officially “detain” black residents. Every single business was burnt to the ground, and 9,000 citizens were left homeless in the winter. It was the biggest riot America ever saw; total devastation of a vital community at the hands of a racist mob.

In the midst of such violence, there were instances of camaraderie and community strength; a number of white residents, such as the Zarrow family (below), hid black citizens in their homes and stores, and the Red Cross was invaluable in providing aid. But recovery wasn’t easy. The financial loss to the black community equalled to billions of dollars today. Nor was the city ever quite the same again; ugly memories were swept under the carpet.

Even though Greenwood rebuilt itself, and while Durham and Richmond continued to thrive into the 30s and 40s, Black Wall Street would soon become a forgotten chapter in history. This rare footage shot by Reverend Solomon Sir Jones, documented African-American life, culture, and success in Oklahoma a few years after the Tulsa Race Riots. His films demonstrate the nuance and diversity of the Black community during this period.

Desegregation played a curious role in its decline. When African Americans were allowed to shop in other (white) neighbourhoods, they often did, and once that captive market was dispersed into the broader market, it was the beginning of the fall. In the 1960s, the government’s urban renewal efforts, contributed to the further decline of these communities, arguably inflicting more permanent damage than any race riots.

This is a history that has not been recaptured in a format that’s accessible to most Americans. Digging up these lesser-known pockets of history are vital to better understanding how Black Wall Street disappeared and why. These are complex, difficult discussions, however if we’re going to look to a better future, we must also remember the past– the good and the bad– and talk about it. And most of all: be inspired by it. Because is this not the ultimate American story? These pioneering entrepreneurs of Black Wall Street– barely out of slavery, with all the odds against them– who built successful companies and businesses from nothing– are these not the ultimate heroes for any young and ambitious individual striving for success? Because if they could do it…heck. Budding entrepreneurs, past, current and future captains of industry, let’s raise a glass to America’s Black Wall Street.