Their abilities don’t come from any artistic establishment. They didn’t have any formal training and they were not influenced by other mainstream artists. Hailing from places like Mississippi, Tallapoosa, and other rural pockets of the deep south, they’re the African American Outsider and Folk artists whose voices and colour palettes explored a world that wasn’t really documented, but whose legacies have often been pushed to the wayside by history. Their work explores everything from the painful legacy of slavery, to segregation; from the need for intersectional feminism, to the power of a simple gesture of love. And their work is as unique as it comes…

Margaret’s Grocery by Reverend Dennis

If you build it, they will come — and if you built like Rev. H.D. Dennis, you’ll go down in local legend. The story of his life’s work can be summed up in Margaret’s Grocery, a kind of shrine he built for his wife in memoriam of her first late husband, who was murdered at a supermarket robbery in the 1970s.

It was a traumatic experience for his love Margaret, and their little grocery store became a place for healing. It’s Starburst colour palette covered every inch of the place, and the Reverend used his WWII brick laying skills to construct a folk art palace like no other. If you ever find yourself off the Highway 61 in Vicksburg, Mississippi, be sure to stop for a gander…

Margaret’s Grocery has sadly fallen into ruin since the couples’ death, but is currently undergoing repairs. To learn more about visiting in the future, drop a letter in the Mississippi Folk Art Foundation’s inbox at Suzisnaps@aol.com.

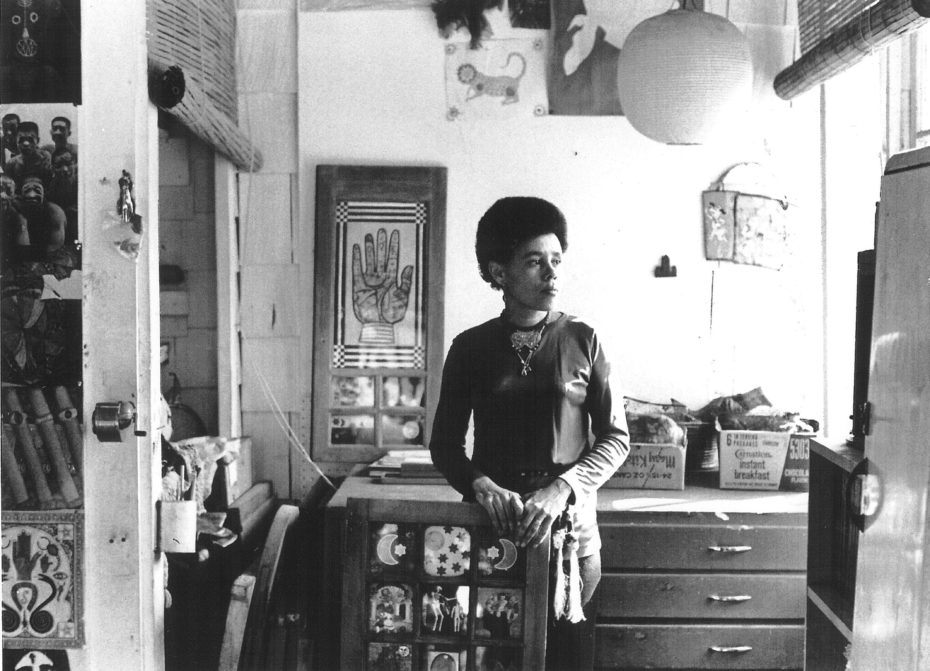

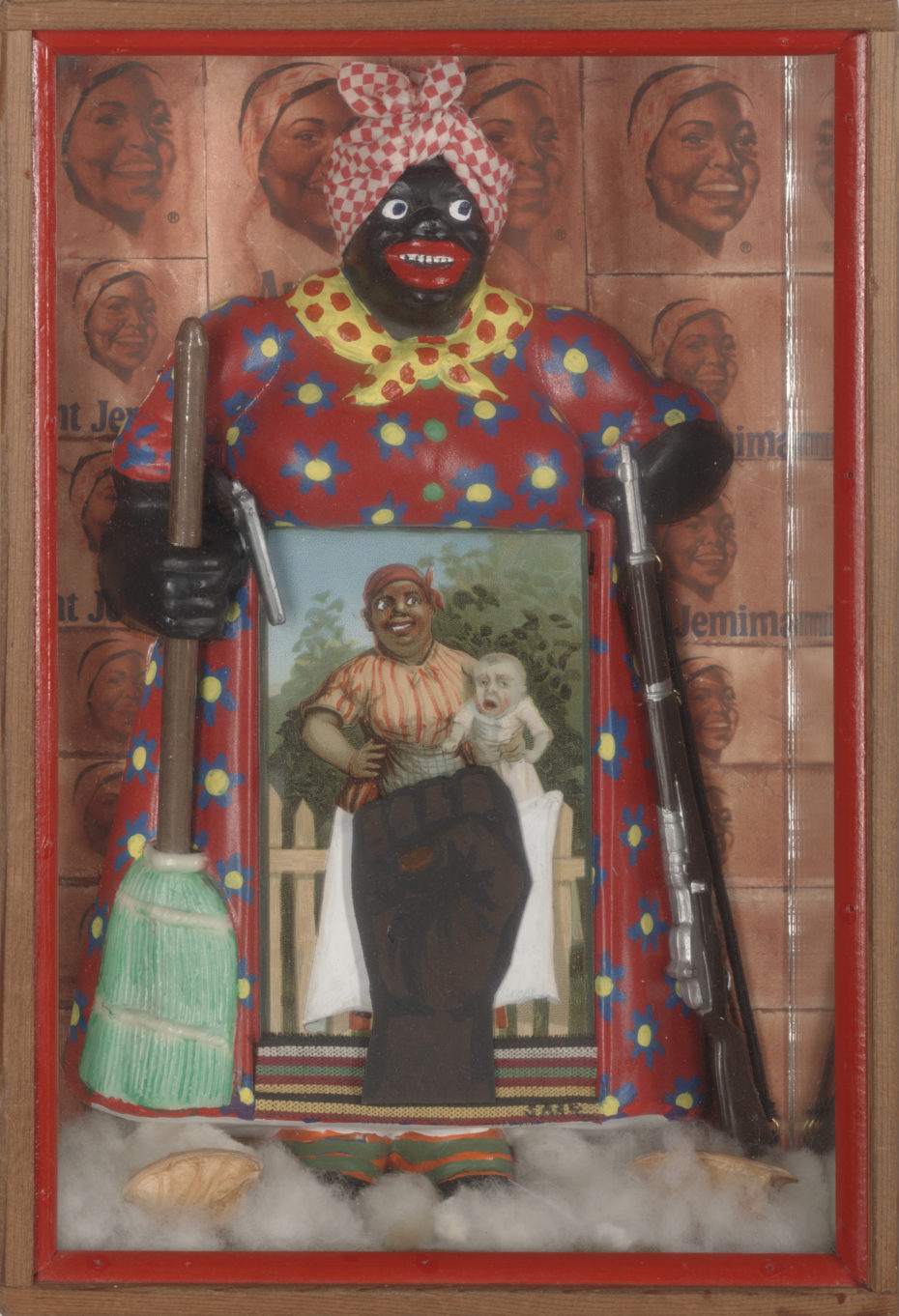

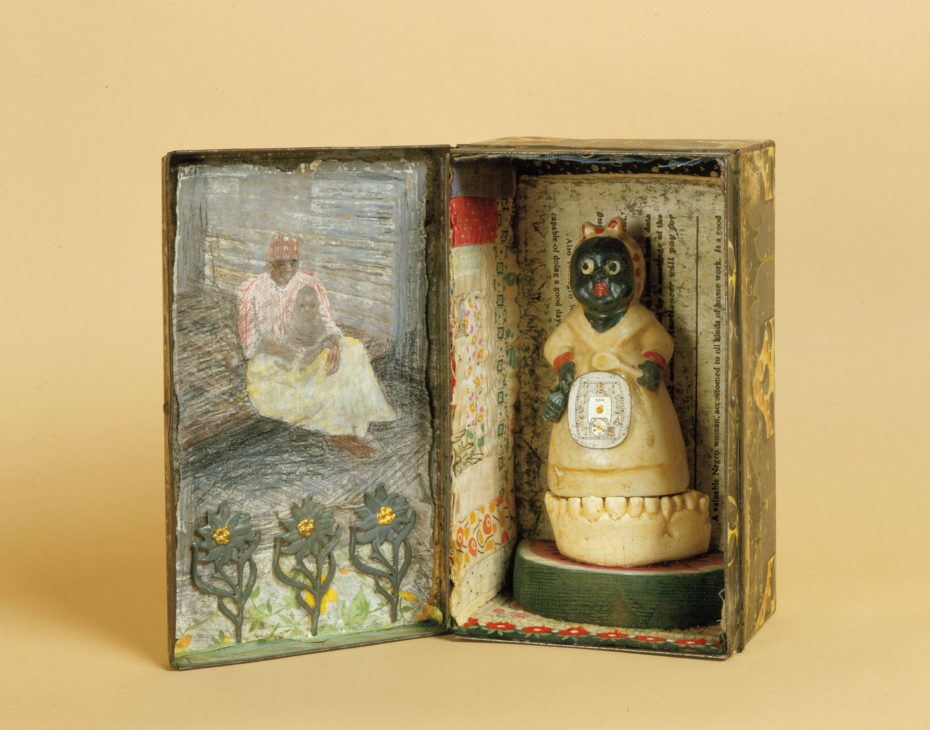

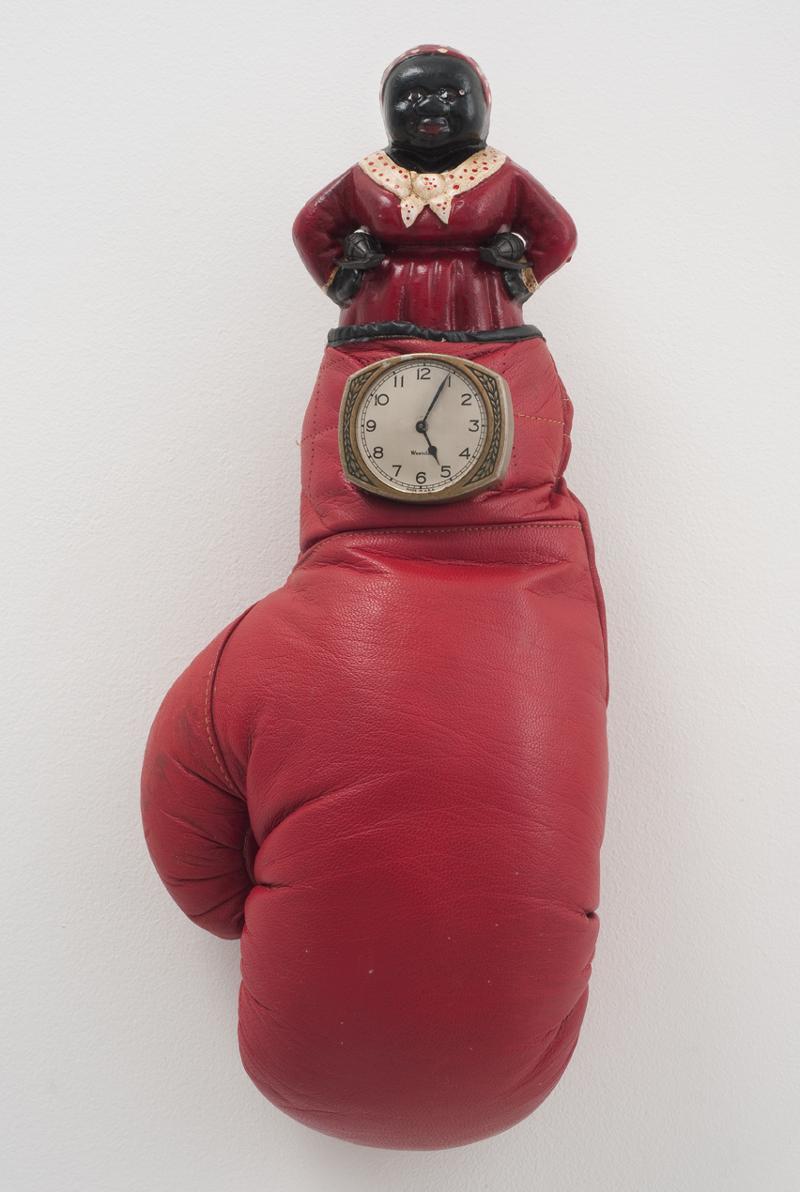

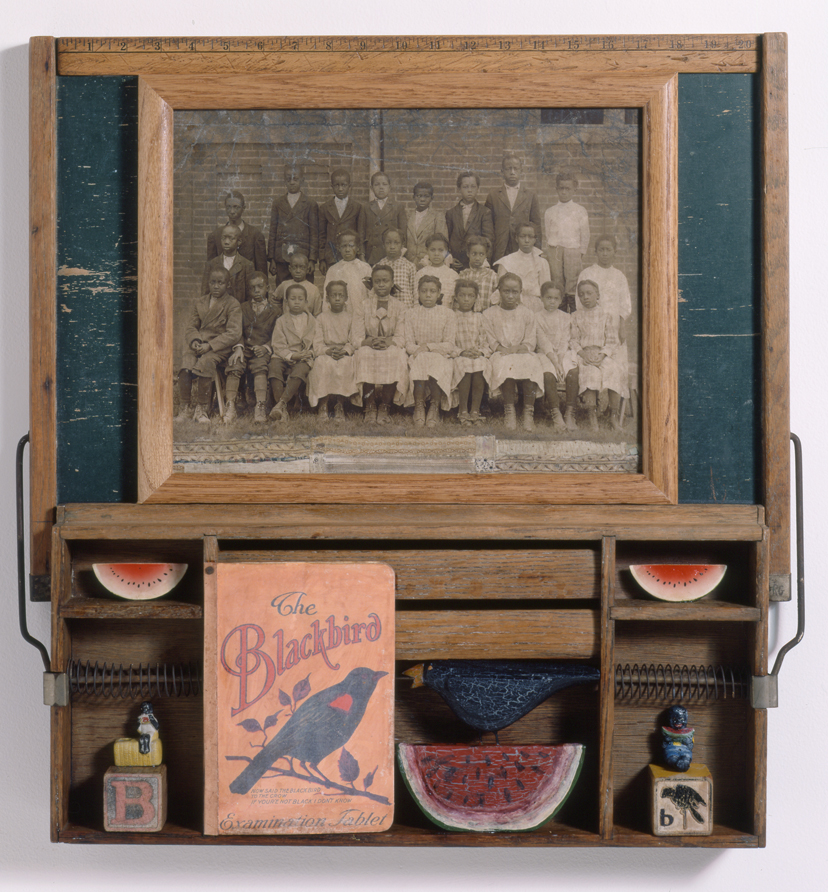

Liberating Aunt Jemima with Betye Saar

Where to begin with Betye Saar? She’s a triple threat as a fierce activist, artist and flea-market thrifter! Betye Saar spent a great deal of her career in art scouring flea markets and junk shops in search of memories (in the guise of advertisements, photographs, toys, household objects and musical instruments). Saar works with these instruments that represent how African Americans have been treated in this country.

One of her most revolutionary pieces was a simple California wine jug with a “black mammy” type label. “In scale, it is small — barely 18 inches tall — but its message couldn’t have been more explosive”, said Los Angeles Times reporter Carolina A. Miranda, “Imprinted on the bottle is a black power fist. It’s degrading kitsch remade into fiery cultural armament.”

A vital figure in the radical L.A. arts scene of the 1970s, she also belonged to the legendary New York-based, black artist collective, Rodeo Caldonia in the 1980s. She was particularly inspired growing up by LA’s Watts Towers, whose construction she watched with her very own eyes (whilst taking notes).

And did we mention she is cool as hell? (Here’s another reminder ↑).

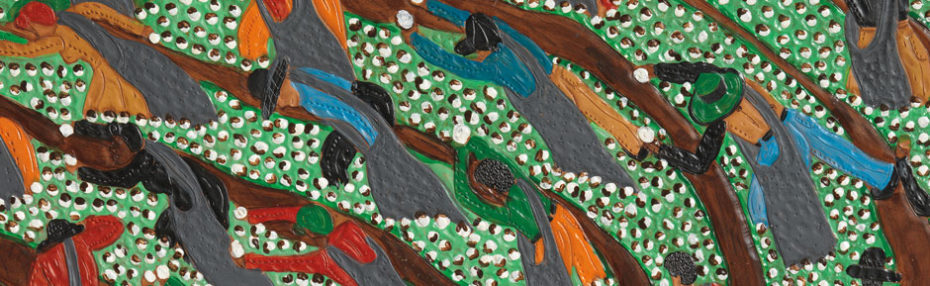

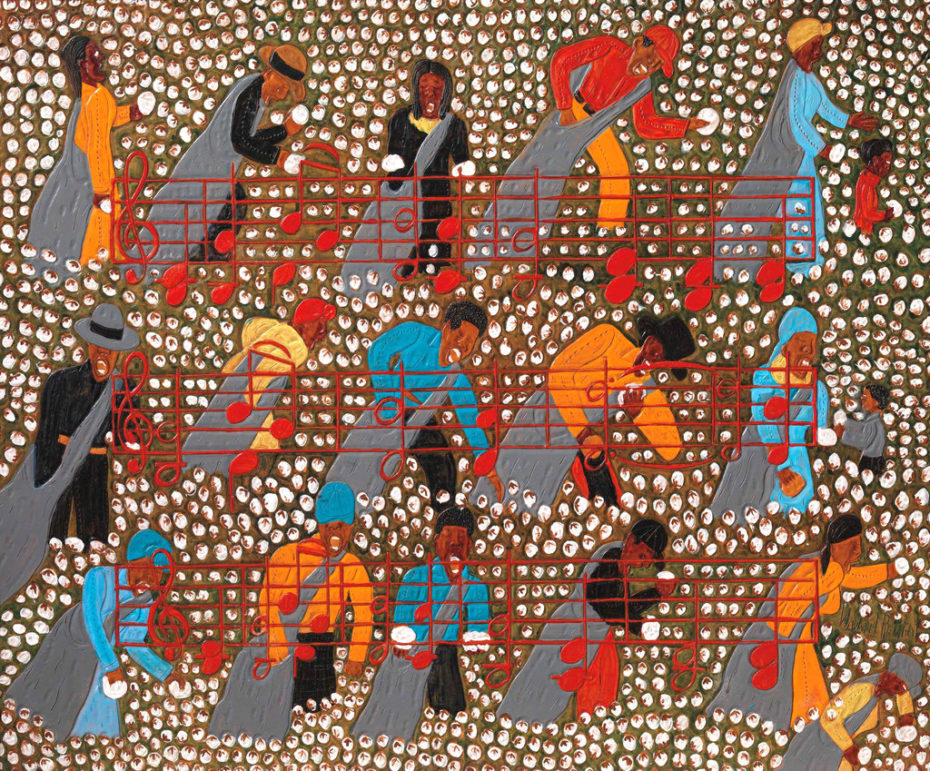

The Leather Paintings of Winfred Rembert

Rembert grew up in Cuthbert, Georgia, where he spent much of his childhood laboring in the cotton fields. Rembert stretches, stains, and etches on leather and creates scenes from the rural Southern town where he was born and raised.

A documentary film about his life, All Me: The Life and Times of Winfred Rembert, was released in 2011, available to watch on iTunes.

From the Graveyard to MoMa: William Edmonson

William Edmonson was the first African American man to have a solo exhibition at the MoMA. He’d spent the majority if his life doing odd jobs and working as a janitor at the women’s hospital in Nashville. When he lost his job there, he decided he was going to become a tombstone carver and after a while he started carving what he called his garden ornaments. They are incredibly architectural carvings, and modern too for 1930s Nashvville.

He sold his sculptures along with selling vegetables. He was first discovered by his neighbour Alfred Starr, a white businessman who owned a chain of movie theaters catering to the black community. Together with his wife, a painter, Starr introduced Edmondson to several artist friends, including a Harper’s Bazaar photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe, who began taking dozens of photographs of Edmondson at work in his backyard shop. She brought her photographs to the director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

He went on to sculpt a number of popular figures such as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and prizefighter Jack Johnson. He died of illness in 1951 and was buried in Nashville’s oldest black cemetery, but it’s unknown whether his grave was marked with a tombstone. If so, it has been lost and his exact grave site is unknown. And to think began his career as a tombstone carver.

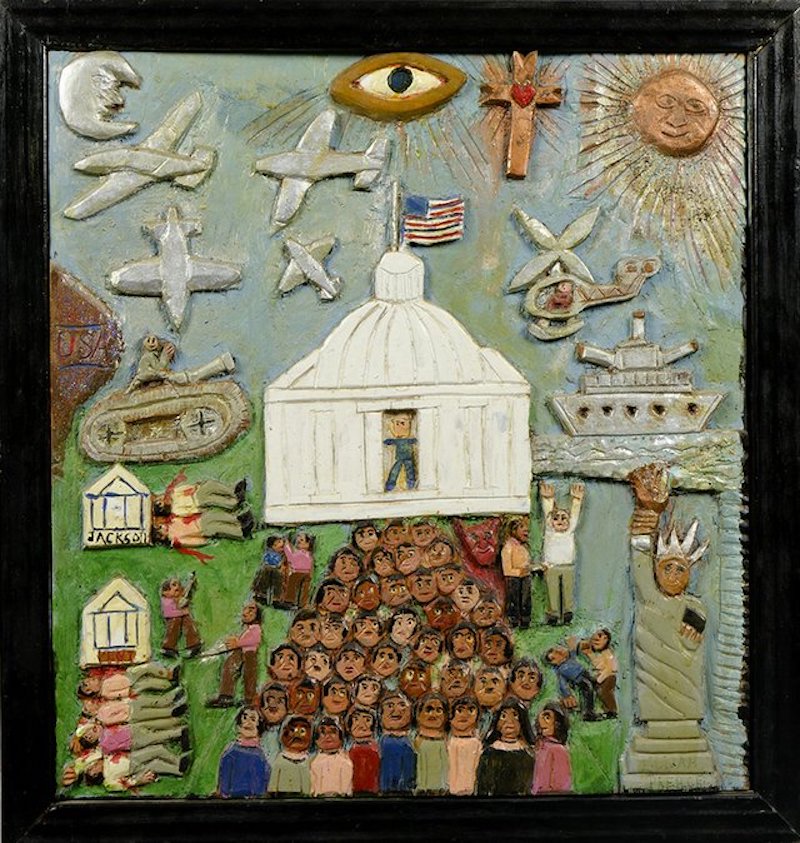

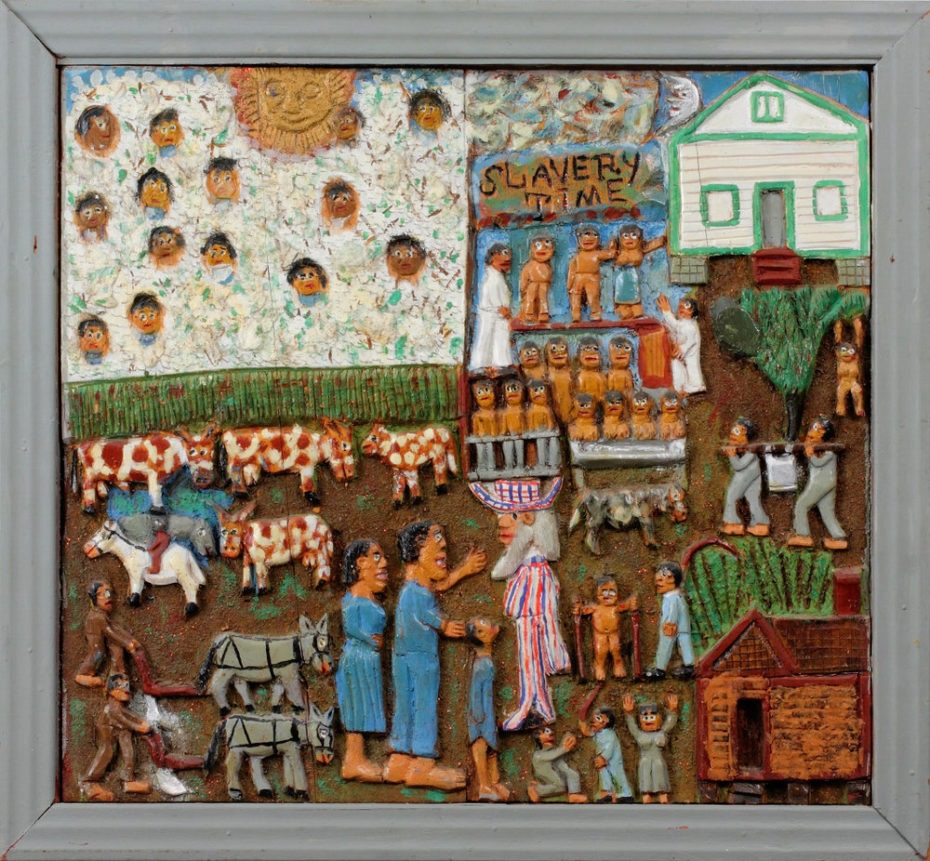

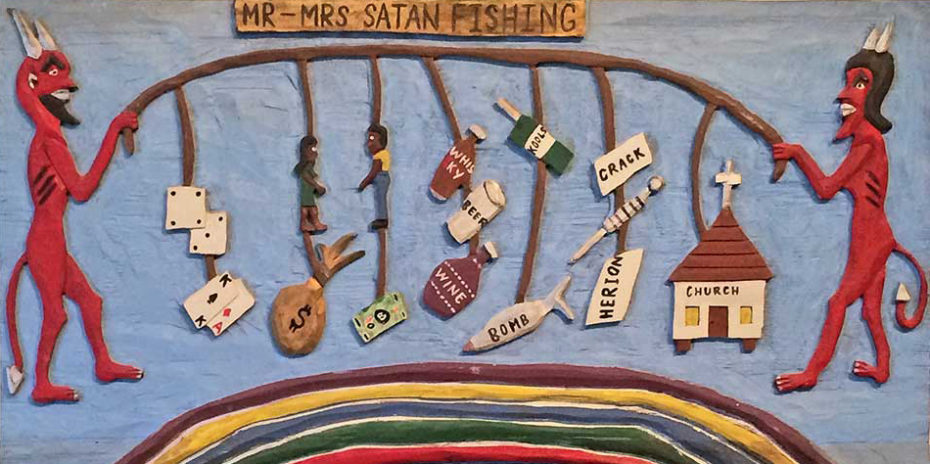

The Woodcarvings of Elijah Pierce and Leroy Almon

Born in 1892 as the son of a former slave, Elijah Pierce was made of staunch character. His older brother Tom gave him a pocket knife to whittle away in his free time growing up on a farm in Mississippi, and, well, the rest is history.

“I’d look at a tree, and I could hardly help it. I’d start carving,” he said, “I carved pictures of cows, hogs, dogs, Indians with a bow and arrow shooting, girls’ names … most anything I could think to put on the bark of a tree.”

He’d road trip around the country with his wife to share his treasures at churches, fairs, and with anyone curious enough to chat. Pierce was honored with the National Heritage Fellowship for his art and influence in the woodcarving community in 1982, 2 years before his death in 1984.

Then there’s Pierce’s prodigé, pictured above to his right. Leroy Almon was born in Tallapoosa, Georgia, and made his way as a shoe salesman and Coca-Cola Co. employee until he bumped into Elijah Pierce at a Baptist Church in Ohio.

When Almon lost his job in ’79, it was Pierce who gave him a new one as a curatorial assistant of sorts. Of course, it wasn’t long until Almon learned the ways of his trade, and carried on the low relief carving tradition with his pocketknife and chisel…

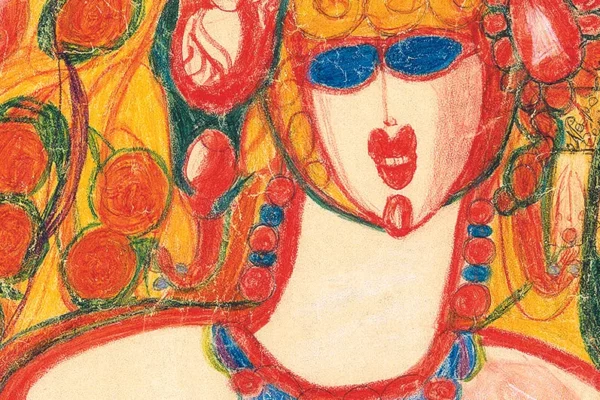

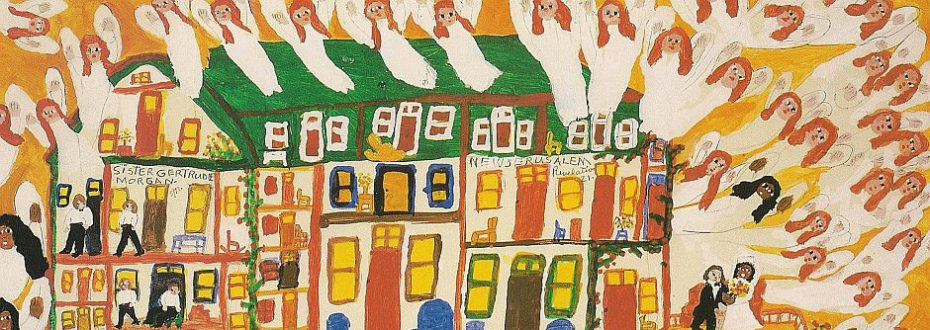

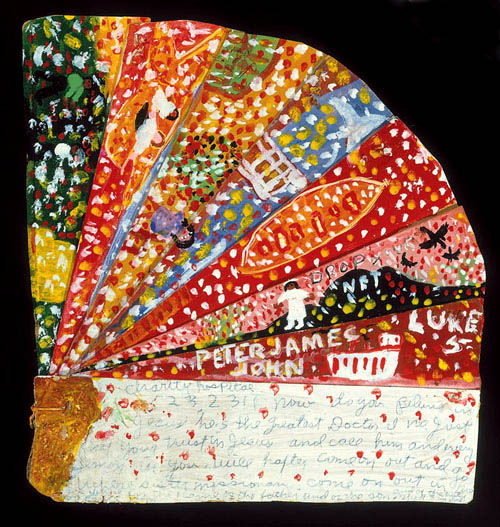

Preaching with her Paintbrush: Sister Gertrude Morgan

Lee Friedlander and Andy Warhol were both fans of her work. She lived in New Orleans where she worked as a street preacher. Around 1960, art dealer Larry Borenstein met Sister Morgan while she was preaching on a street corner in the French Quarter with a paper megaphone. He invited her to perform and exhibit work in his art gallery. Using inexpensive materials she had at hand, Sister Morgan painted on paper, toilet rolls, plastic pitchers, paper megaphones, scrap wood, lampshades, paper fans and styrofoam trays.

In 1956, Sister Gertrude Morgan had claimed to received a revelation from God urging her to paint, and used her early paintings as visual aids in her sermons and teachings, often with children. But in the 1970s, her work began being included in many groundbreaking exhibitions of visionary and folk art. Her self-taught skills show a sophistication composition and colour; stemming out from the canvas like veins. Outsider art is an often male-dominated field, but Sister Gertrude is a fine example of a female self-taught black artist.

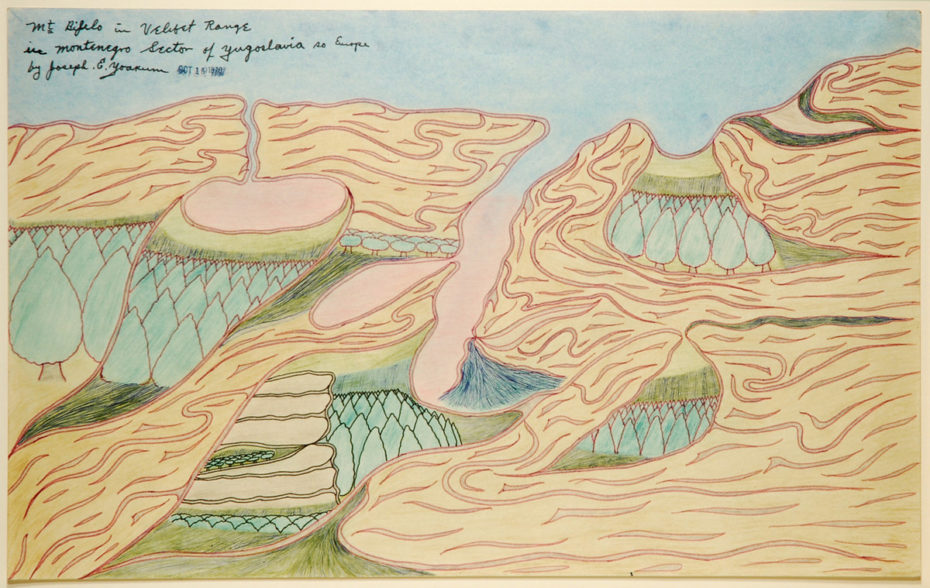

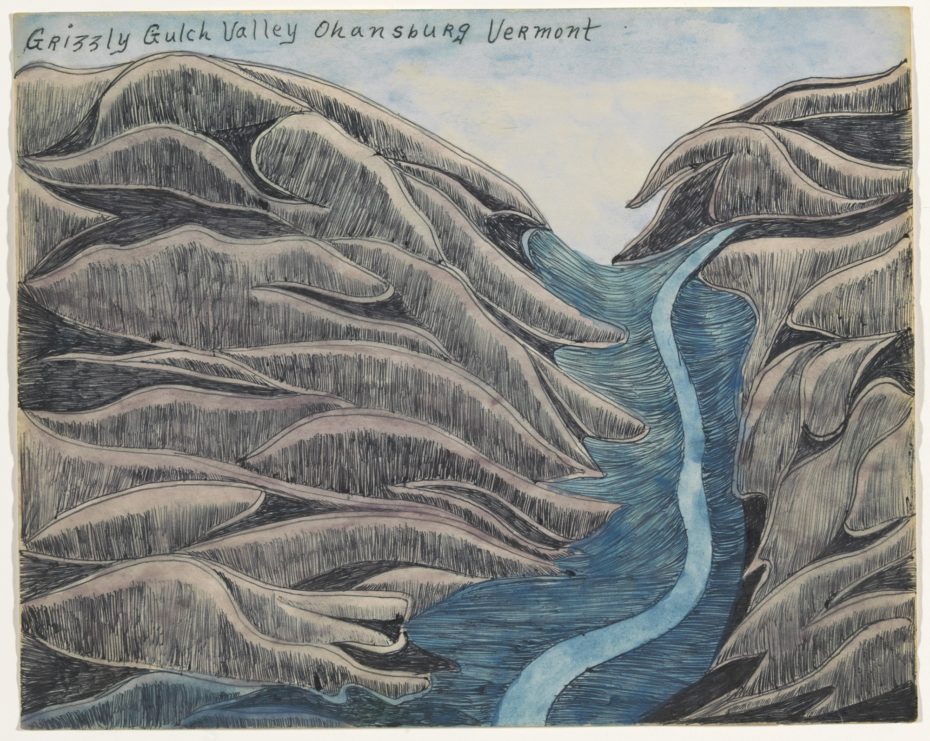

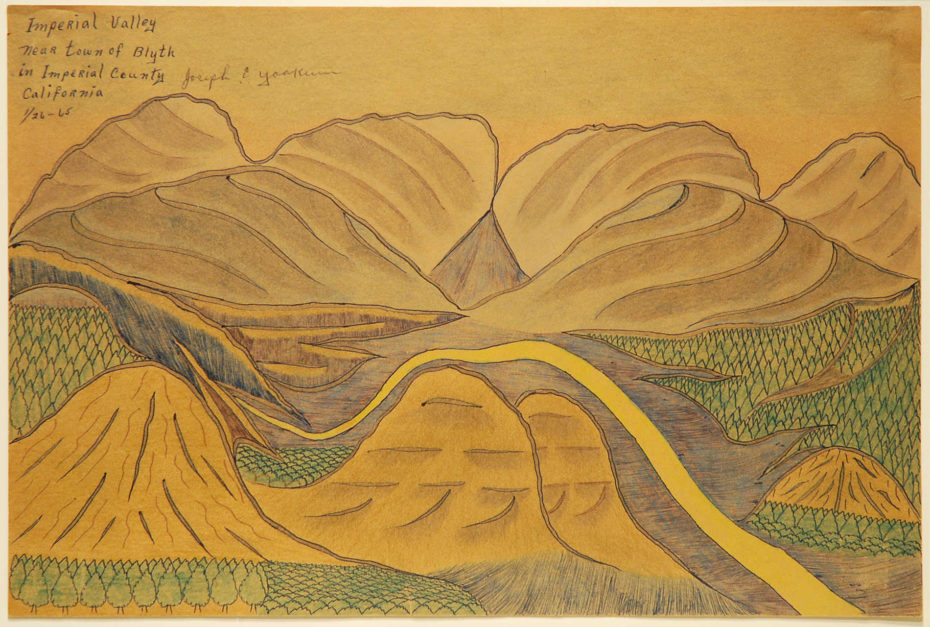

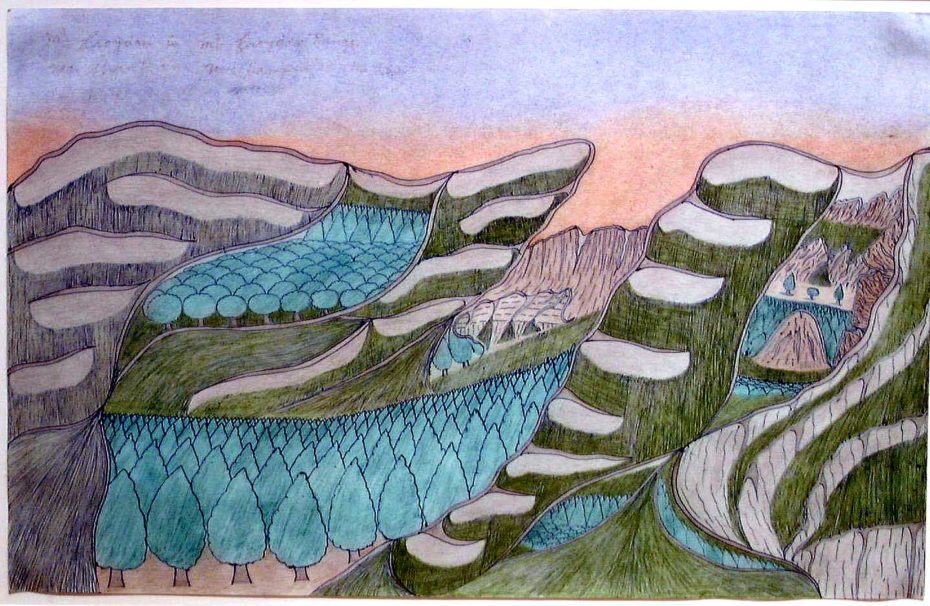

The Native American Dreams of Joseph Yoakum

Though his official records note that Yoakum was born in Missouri, he took pride in claiming he was born on a Navajo reservation; his mother a former slave of mixed Cherokee, African-American descent and his father a Cherokee Indian.

Yoakum left his family’s farm when he was just nine years old to join the circus and traveled across the U.S. with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and the Ringling Brothers as a billposter. He later traveled to Europe as a stowaway.

He returned to America in 1908 and spent most of his later life moving around the country working odd jobs. He worked in a coal mine to support his family. In 1946, Yoakum was briefly committed to a psychiatric hospital and soon after began drawing on a regular basis.

He was discovered in a coffee shop in Chicago in 1962, where he’d hung some of his drawings. Halstead, an artist and instructor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, became the greatest promoter of Yoakum’s work during his lifetime. He believed that his story was “more invention than reality… in part myth, Yoakum’s life as he would have wished to have lived it.”

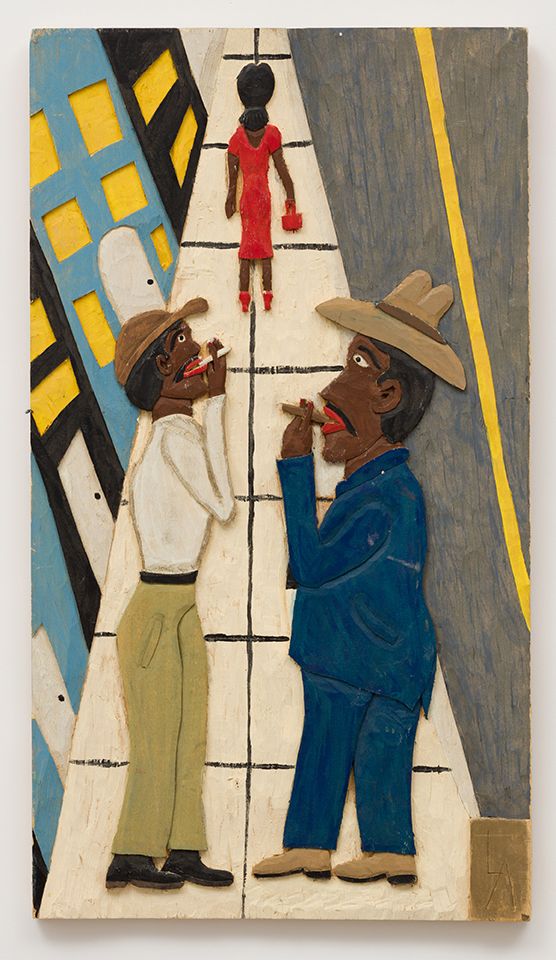

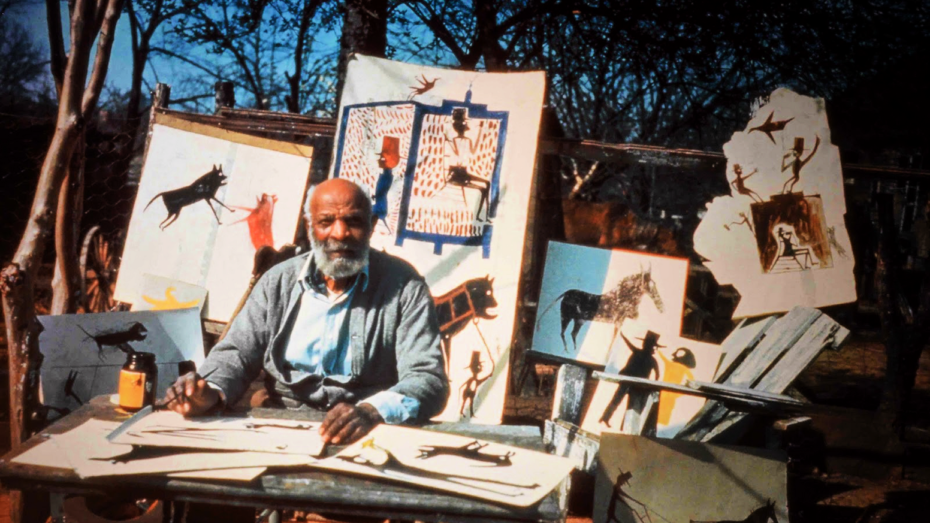

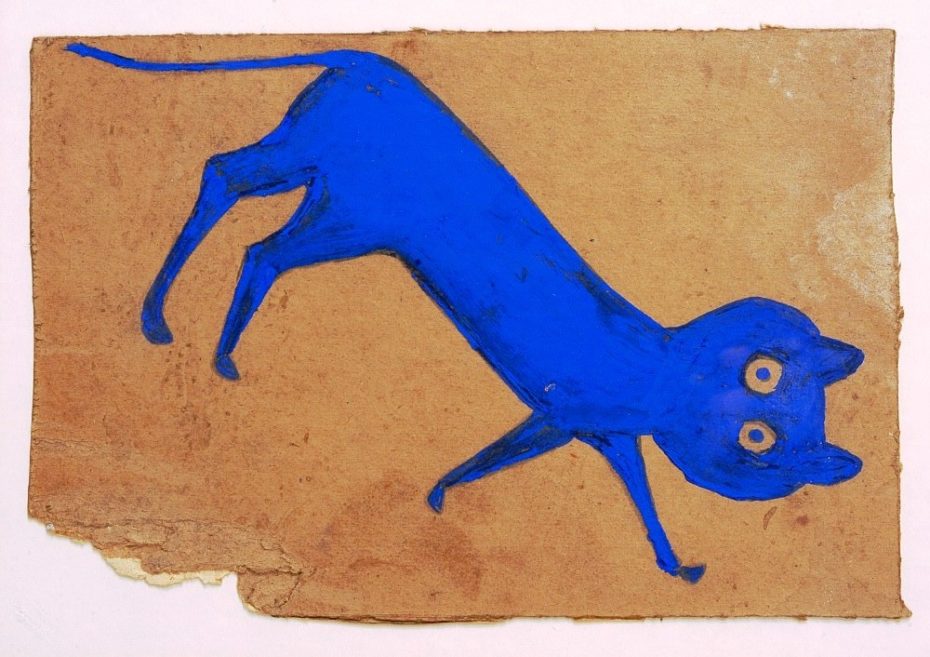

Chasing Ghosts with Bill Traylor

Bill Traylor lived most of his life on a plantation and moved to Montgomery, Alabama in his old age. Suffering from ill health, he couldn’t find a job and spent a lot of his time sitting on a doorstep in a very vibrant african American part of the city. He began to draw what he saw.

Known for creating abstract constructions of his memories of plantation life and animated figures, instead of disappearing, Bill Traylor soared…

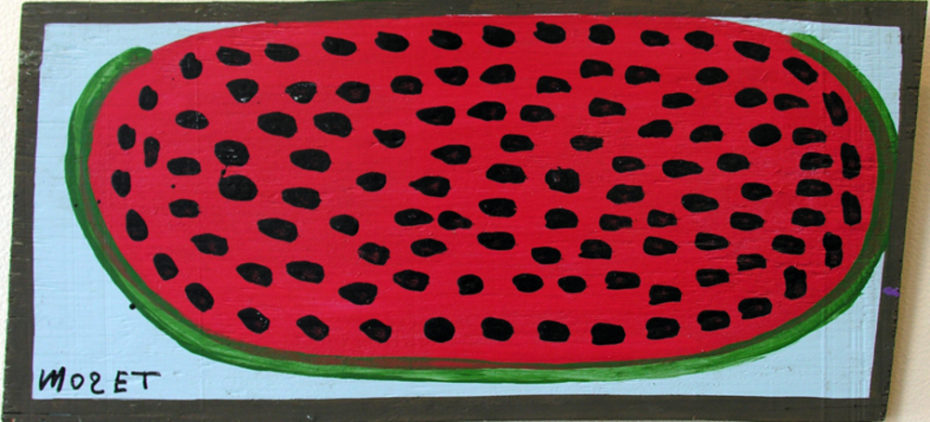

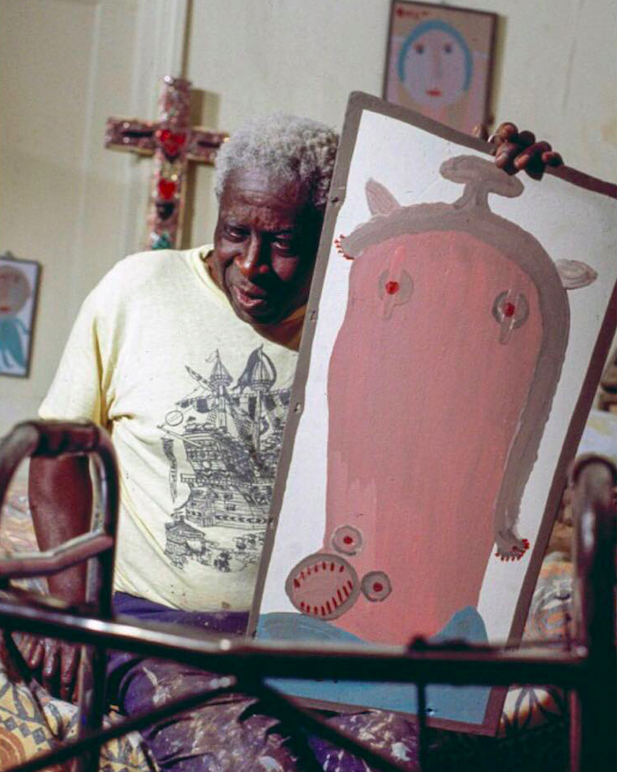

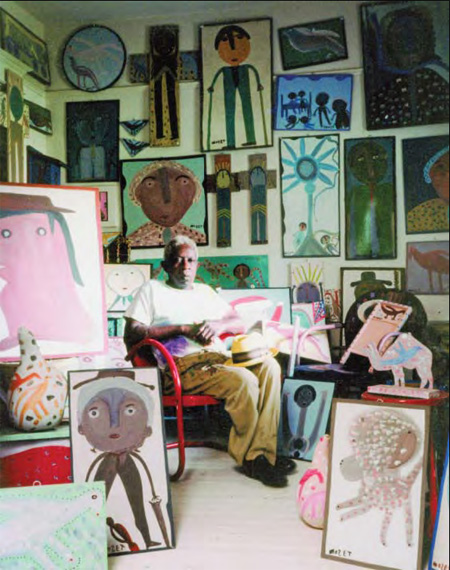

Will the Real Mose T please Stand Up!

Moses Ernest Tolliver was one of 12 children and had 13 children of is own. Relatives of Tolliver have imitated his style and signed their work as he did, with his signature backwards “s”, making it sometimes difficult for collectors to find an original painting. Since his death in 2006, a true Mose T painting is valued in the thousands of dollars and his work hangs at the American Folk Art Museum in New York and the Smithsonian Institution.

His art not only tells the story of his own creative vision, but his strength in the face various physical disabilities. He was born in 1924 to sharecropper parents in Montgomery, Alabama. “Tree roots, that’s what I started with,” he said, “Old tree stumps. I found them things out in old vacant lots. I seen somebody with some when I was ’round about maybe eighteen or nineteen.”

First he decorated the trees, and later made his own paintings to dangle from them in his yard. His art began as a release from depression and drink and he often credits his dyslexia as an inadvertent factor in his gravitation towards a medium that required no language — just paint. “I used to get cow heads and paint them. Cow bones too,” he said, “If I could find some of them things now it would sell better than anything in this house. I done some fish stuffing too. People give me fish to fix up. ” His backwards “Mose T” signature has since become iconic.

Tragedy struck in the 1960s when his legs were crushed by a load of marble from a furniture factory he worked in. It was a blow to Tolliver, but a time in his life when he started churning out incredible self-portraits. By the 1980s his plywood paintings had actually become quite famous, with even Nancy Reagan becoming a fan of his work. When he died in 2006, it was as one of the most cherished African American folk artists in modern history.

In an age where anyone can find both inspiration and an audience through a handheld device, the idea of an artist being removed from society; the thrill of discovering such talent in obscurity, seems less and less possible. But there will arguably always be art that truly can’t be taught, and perhaps this can help paint the picture of where this outsider movement is headed.