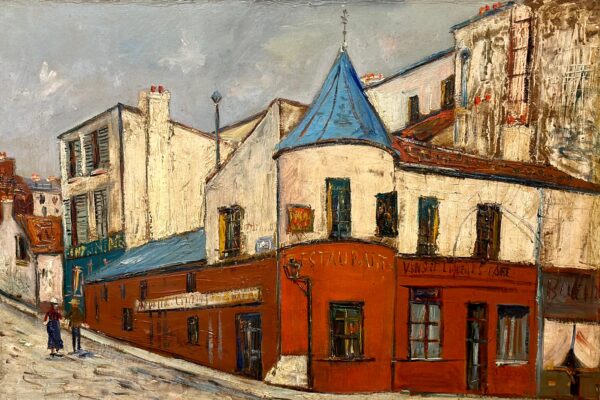

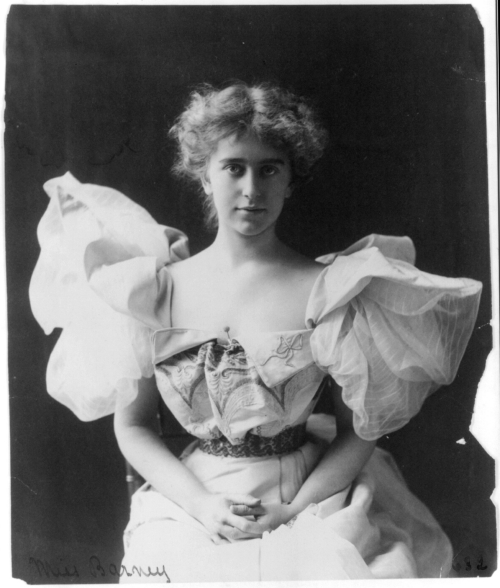

She was the kind of woman who never belonged to anyone but herself. At least, when it came to love. But for Natalie Clifford Barney, life overflowed with colour, creativity, and passion in Paris’ Left Bank during one of city’s most romantic periods. Think of her as a lesser-known Gertrude Stein, albeit one who curated a literary salon with just as much clout for over 60 years. Under the roof of her enchanting home in the 6th arrondissement, the likes of Colette, Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald, T. S Eliot, James Joyce, Rodin, Hemingway and other leading figures of the Lost Generation found not just a safe haven to be weird, but a temple for friendship. And not just any temple– a mysterious masonic temple.

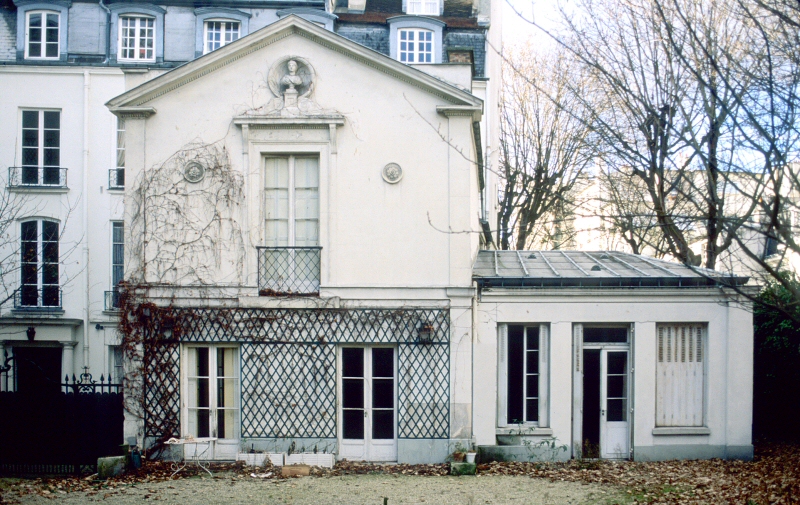

“What made No. 20 a kind of miracle on the Left Bank was its garden, a small oasis in a jungle of tightly packed streets,” wrote her friend Eyre de Lanux, “a remnant of the great 17th and and 18th century gardens which once stretched from the rue Jacob down to the Seine”. It contained a tiny Doric “Temple d’Amitie” (Temple of Friendship).

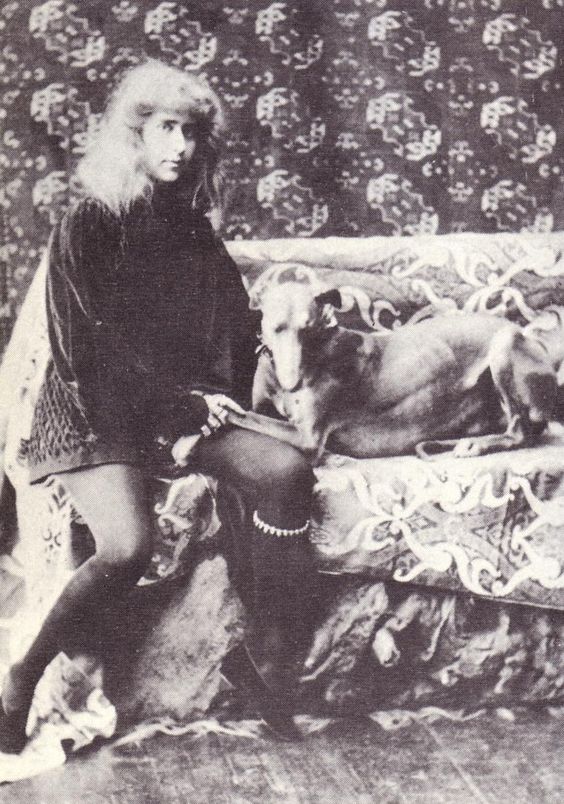

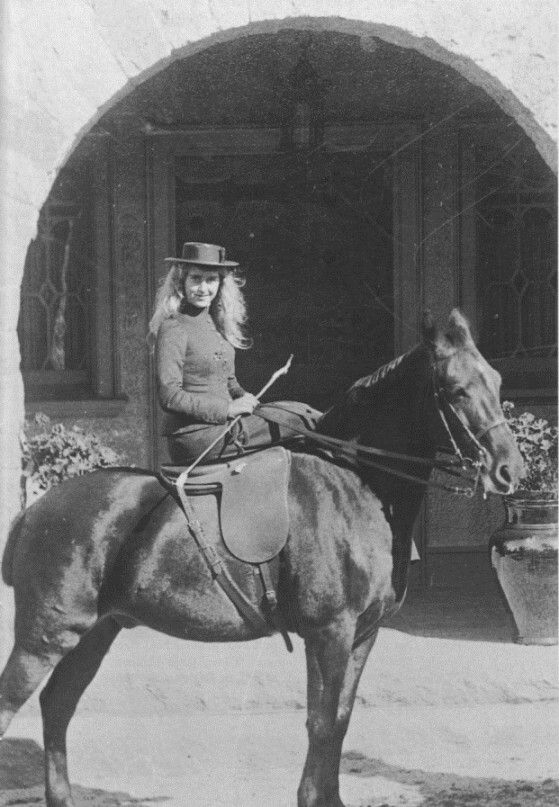

Barney’s life is bookmarked by a series of charismatic female lovers, but she always saw herself as a keeper of talent, not hearts. She became known as “the Amazon” and writers would spend hot summer nights in her garden, eating her famous chocolate cake and discussing the work of her idol Sappho, the first lesbian poet, and the sanctuary of her Greek island of Lesbos.

“We would have 20-60-100 people [over],” said de Lanux, “Somehow we could seat everybody. We served sandwiches, cakes, fruit, crystallised strawberries, tea, port, gin, whiskey, everything. The whiskey always disappeared fast when we had American guests.”

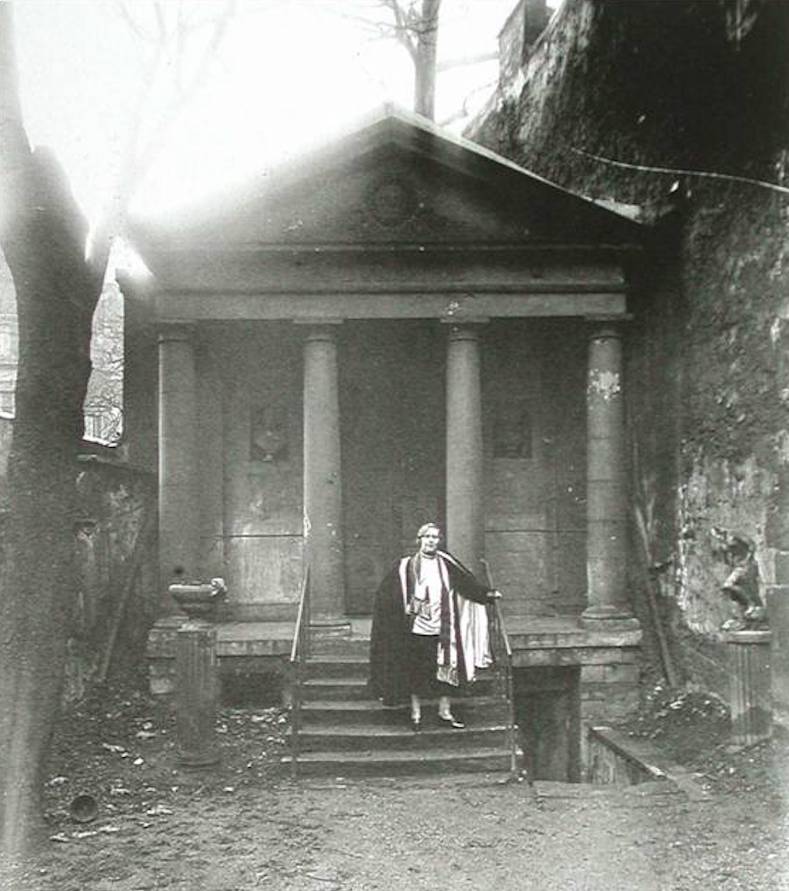

As Hemingway put it, “There are so many salons in Paris tended to by expats, but Ms. Barney’s seems to be the only one with an actual temple.” One of the most curious secrets of the Parisian Left Bank, the Doric structure’s origins are undocumented, but it’s believed to date back to the first empire in the 18th century. But what makes it so mysterious is the fact that local historians discovered that the Temple of Friendship is located exactly 500 meters from both the Mona Lisa at the Louvre and the sundial at the church of Saint Sulpice– (Da Vinci Code fans, eat your heart out).

These days, if you linger by the door of 20-22 rue Jacob, where Barney held court for so many decades, you may be able to sneak inside to get a peak of the legendary space with a link to some of the world’s most remarkable (and conspiracy-prone) sites.

Coincidences or a secret message? The intrigue doesn’t end there. The Germans cleared the Temple out during World War II, and found that it led to an underground cave and a passage going underneath the Seine to the Louvre. In fact, under the pen of Martin Langfield in The Secret Fire (2009), the basement of the Temple of Friendship becomes the secret rendezvous of esoteric circles during the War, allowing for access to the Parisian Catacombs.

There was also masonic star in the middle of the parquet, visible in the above photograph below, under the tenancy of Barney. The house on rue Jacob, however, was bought by one Nicolas Simon Delamarche and his wife in the late 18th century. Local historians uncovered records conserved in the French National library confirming that Monsieur Delamarche was initiated in a French masonry order in 1777, and it’s thus been suggested that the Temple may have been used in the initiation ceremonies for new candidates.

Miss Barney used the temple as a painting studio, supposedly, and for private one-on-one meetings with members of her salon. She decorated the interior with old rustic Spanish furniture. When she had guests, the fireplace would always be lit and open to visitors. As to the truth of its origins, Barney made sure the temple stayed true to its name as the “Temple d’Amitié”.

Barney’s neighbour once wrote:

“The only danger that I ran into on Jacob Street was the attraction of the shadow… the vague smell of invisible lilacs coming from the garden neighbour. This garden, I could only glimpse… I did not know that this haunt of restless leaves marked the favourite residence of Remy de Gourmont and the garden of his “Amazon”. Much later, I crossed the fence of the garden, I visited the small temple that rose to friendship”.

That neighbour was none other than the French writer Colette, who would a few years later find herself dancing in front of Barney’s temple of friendship — a virtue that she held in the highest regard. “I think friendship is the most lasting, and the freest of passing emotions,” said Barney, “I’ve never given up my friends. They’ve given me up, but I’ve never given them up.”

Rather than become a rival of Gertrude Stein, the two literary powerhouses became friends, and went for walks around the quartier every night with Stein’s dog.

In her 96 years on the planet, Barney published five volumes of poetry (all in French), and various other memoirs and epigrams. Most famously, she inspired the courtesan Liane de Pougy’s Idylle sapphique, or Sapphic Idyll, in 1901, and Radclyffe Hall’s legendary lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness, in 1928.

When you’re in love you never really know whether your elation comes from the qualities of the one you love, or if it attributes them to her; whether the light which surrounds her like a halo comes from you, from her, or from the meeting of your sparks.

—Natalie Clifford Barney

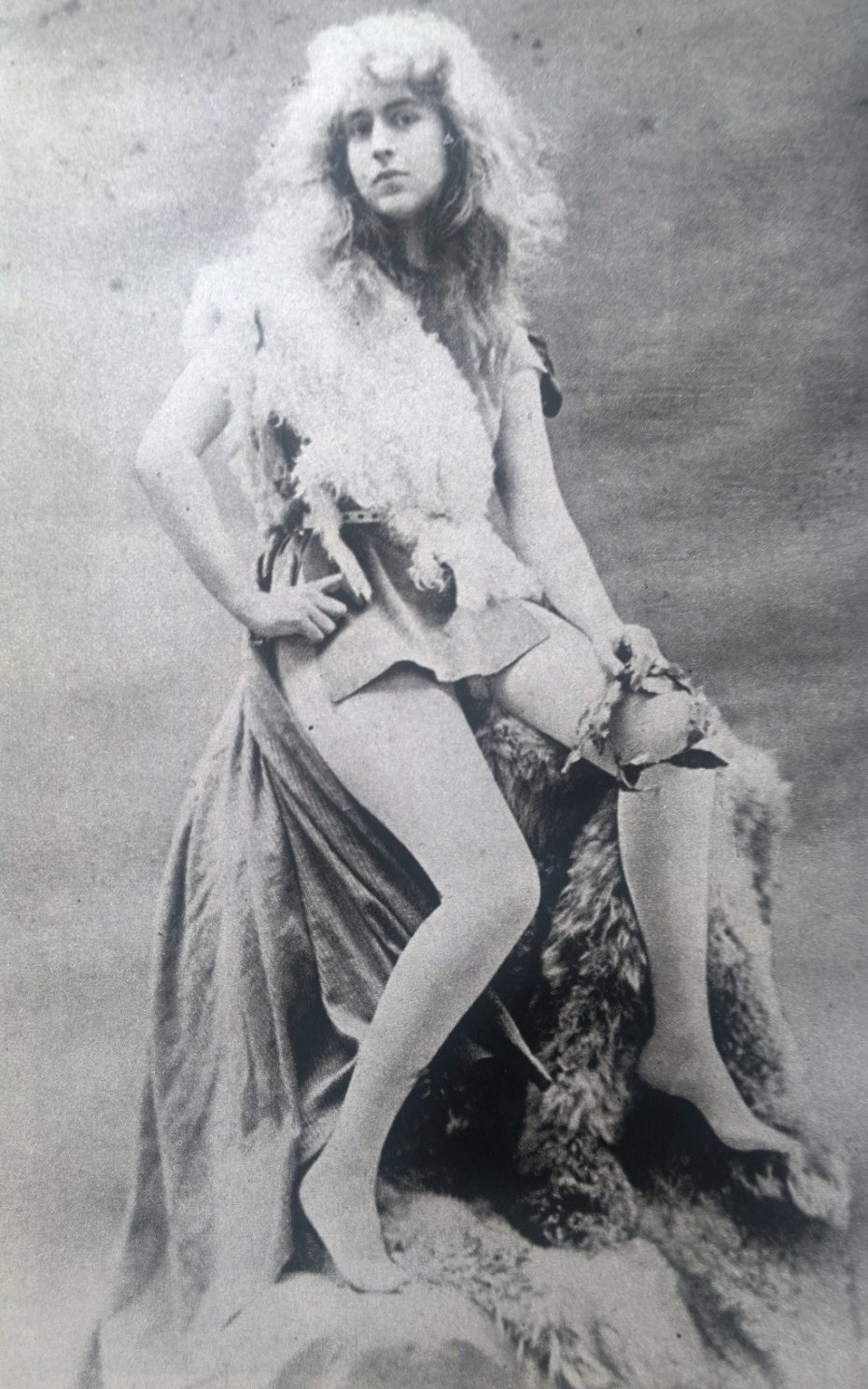

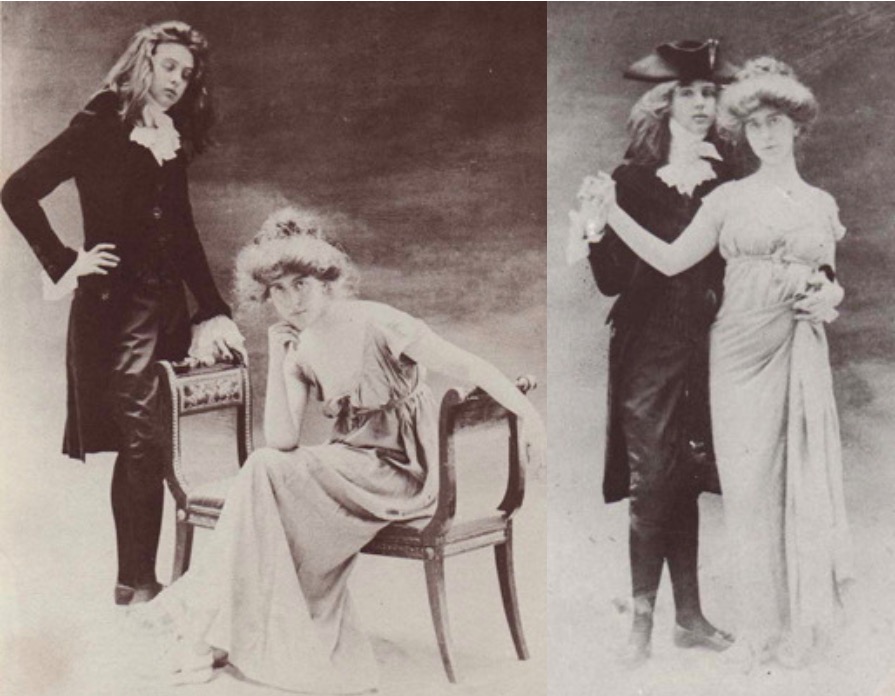

Barney was also unabashedly open about being a lesbian; “My queerness,” she said, “is not a vice, is not deliberate, and harms no one”. In her memoirs, she says she knew she was gay before puberty, and might’ve been one of the youngest ladies to ever charm Liane de Pougy, “the woman who ruled Paris from her bed“. In 1899, after seeing her at a dance hall in Paris, Barney dressed up in a page costume to knock on her door as a “page of love”, reciting Sappho’s fragments to win her over. It worked.

Barney originally hailed from Dayton Ohio. She came from serious railroad manufacturing money, and, as tends to happen to children in affluent families, was looking to rebel. She played rough, preferred to ride saddle-back, and seemed to have an inner compass for other other misfits with creative genius.

She was only 5 years old when she had an encounter that changed her life forever at a hotel in New York — if not only because the man’s niece, Dolly, would become one of her most influential lovers. “A young group of boys were throwing candy cherries into my blonde hair at this hotel,” she told the BBC in the 1960s, “And this man scooped me up on his knee, and told me a story”. It was Oscar Wilde.

The dandy Wilde’s words sparked something in Barney, but it was through her own tireless efforts that her salon attendees, and particularly its women, felt supported. She also fought tooth and nail with her father to publish her work due to its “lesbian undertones,” writing under the pseudonym Tryphé until his death.

She chose Paris for its liberal society, and became bilingual in French (she’d already studied it in the States). In 1927, she founded L’Acadmie des Femmes, or, The French Women’s Academy in 1927. It was an answer to the boys’ club that was, and still pretty much is, L’Acadamie Française, a 40-person society founded under Louis XIII meant to celebrate the brightest French citizens in the Arts and Sciences called “the Immortals.”

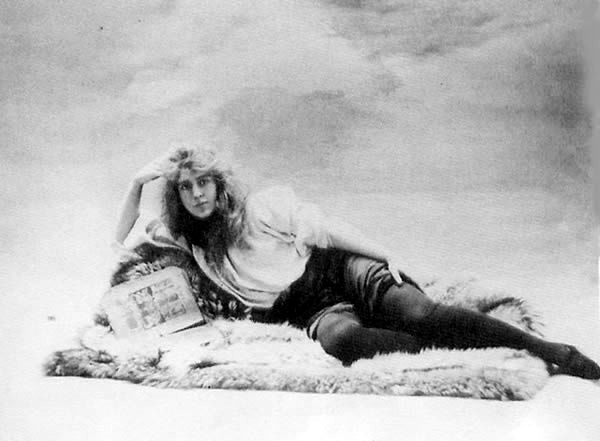

Of course, we can’t talk about Barney without drawing up brief compendium of her lovers, who meant just as much to her sexual autonomy as they did her creativity. First came Eva Palmer-Sikelianos, who Barney saw as a kind of medieval maiden with her “ankle length red hair, sea-green eyes, and pale complexion”.

She would actually end up marrying a man, Angelos Sikelianos, a Greek poet and playwright who helped her revive the Delphic Festival in Greece in the late 1920s:

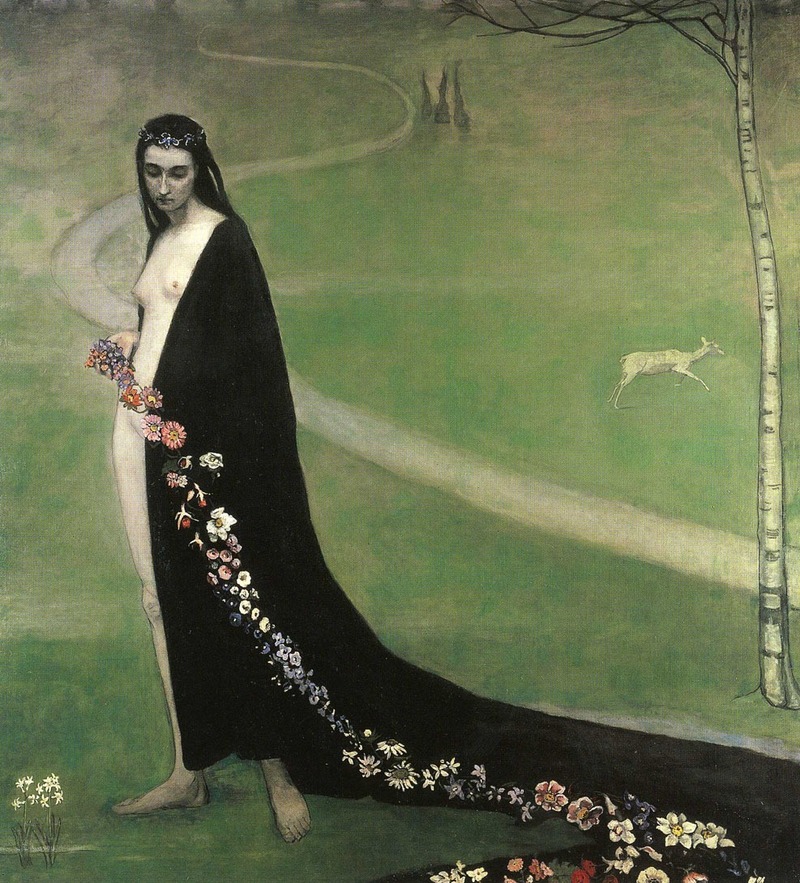

Then there was Renée Vivien. Barney was impressed by the young Brit’s French poetry, saying it was “haunted by the desire for death”. She became Vivien’s muse in Paris, and together they made a pilgrimage to the island of Lesbos to love freely and study Sappho’s fragments.

But their’s was always a tempestuous relationship. Vivien wasn’t on-board for a non-monogamous relationship. They fought constantly, and Vivien suffered from alcoholism and depression. In an attempt to save her from her depression, Barney went looking for a new home in Paris, where the couple could start fresh, and it was at this time, in the Spring of 1909, that she found the enchanting property at rue Jacob with its temple of friendship. Barney paid 6000 France a month for the house. But Vivien would never have the chance to make a home there with her.

“Her life was a long suicide,” said Barney about her love’s death in 1909, “Everything turned to dust and ashes in her hands.” Indeed, Renée Vivien committed suicide right before they moved in.

Afterwards, Barney took lovers like the Duchess of Clermont-Tonnerre, and Colette; Oscar Wilde’s niece, Dolly, and American portrait painter Romaine Brookes, with whom she had her longest relationship.

In fact, it was only Wilde who gave Brookes a run for her money, and the painter finally threatened to leave her. Perhaps not the best tactic to win over Barney, who once said, “I love the love of those who are far enough away. It becomes whatever I wish to believe it.”

On a sidenote, Brookes’ work is also worth checking out:

Barney tended to her salon into her old age, having welcomed everyone from Proust to Truman Capote into her temple, and even allowing for the filming of Feu Follet, the 1963 film by Louis Malle in which Jeanne Moreau’s character explore its gardens. But before you dive into that, have a visit with Barney herself at the temple:

By the second half of the 20th century, following the war, the salon fell into a period of silence. Many of the friends and great writers that had passed through her temple had died or left Paris years ago. The garden became overgrown, vines almost engulfed the temple and the home began falling further and further into disrepair. The world seemed to have forgotten rue Jacob by the 1960s, and the house eventually went up for sale. A 90 year old Miss Barney was still living there as a tenant, but the new buyers took her to tribunal to have her evicted so they could begin renovation. The tactless eviction shocked Paris and even The New York Times protested the careless treatment of Miss Barney and her historic salon.

“My living room is a monument of contemporary literature: no one has the right to modify it,” Barney protested in 1968. An architect was summoned to her apartments to review its state and decided work should begin without delay. The builders and carpenters descended on 22 Rue Jacob and began destroying 60 years of history– gutting everything except the kitchen. The new owner had plans to convert the temple into a rented studio, but thankfully, their plans were thwarted, and the pavilion was classed a historic monument. Unable to live on a construction site, the American poet left the house, vowing to return the following Spring. In 1972, at the age of 96, Nathalie Barney died at the Hotel Meurice, where she had found refuge. She never did get to return to her temple of friendship.

At first, when an idea, a poem, or the desire to write takes hold of you, work is a pleasure, a delight, and your enthusiasm knows no bounds. But later on you work with difficulty, doggedly, desperately. For once you have committed yourself to a particular work, inspiration changes its form and becomes an obsession, like a love-affair… which haunts you night and day! Once at grips with a work, we must master it completely before we can recover our idleness.

—Natalie Clifford Barney

A sad tale indeed, proving the term “Lost Generation” more appropriate than ever, but one that nonetheless adds new intrigue and questions for us regarding the literary circle of early 20th century Paris. As they gathered in Nathalie’s back garden, dancing in front of the Masonic temple after dark, was it always just literature on the agenda? Could it be that some of the 20th century’s most important literary figures were also practicing freemasons? Was Hemingway a member of the shadowy cabal of the Illuminati? It sure makes for a fun conspiracy theory!