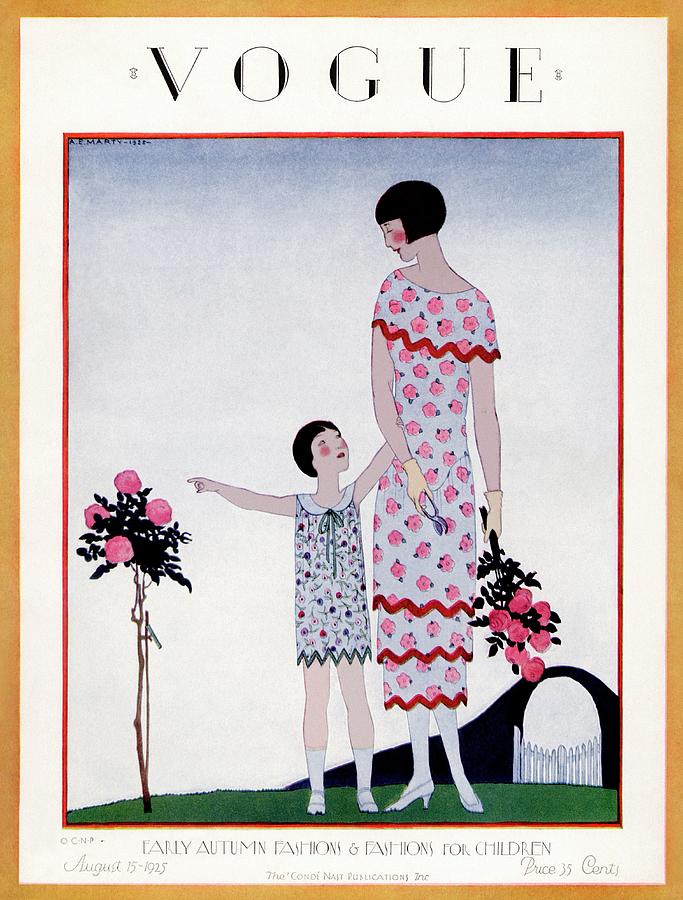

Pochoir was a damn delicate practice, and it was inextricably bound to the star of Paris’ Golden Age of Illustration, André E. Marty. The Frenchman and his stencil-centric drawing or pochoir method defined the aesthetics of a generation, especially for the high fashion set.

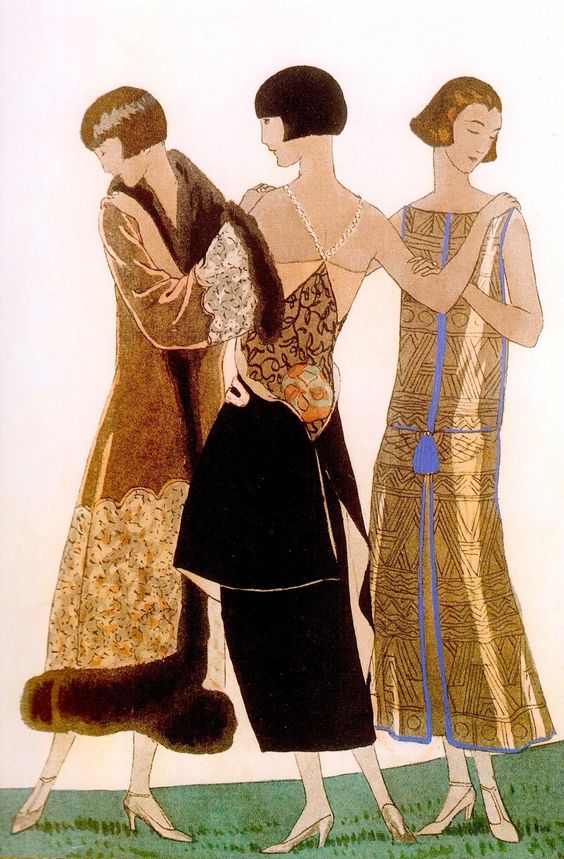

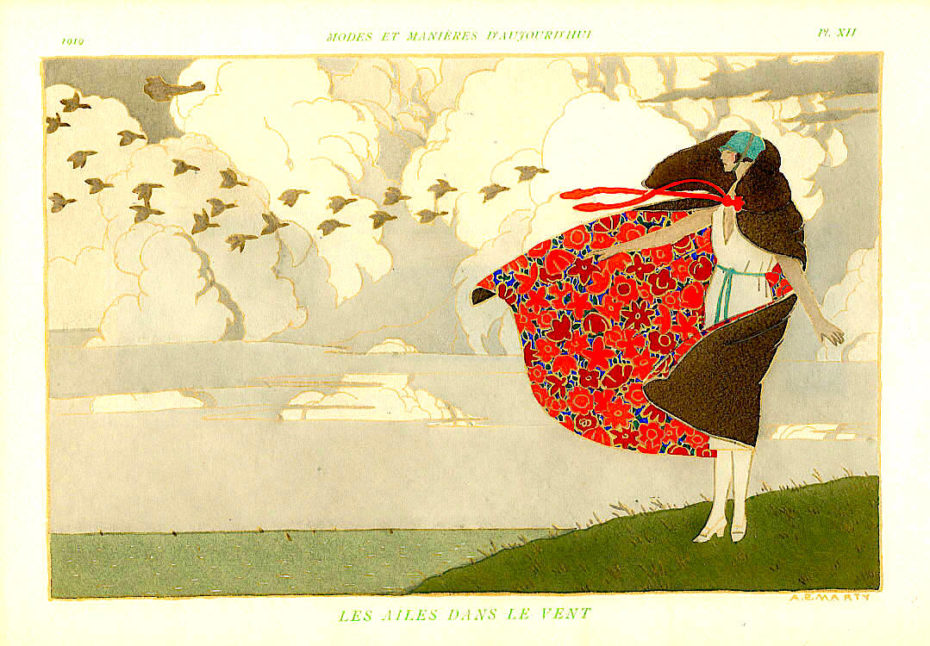

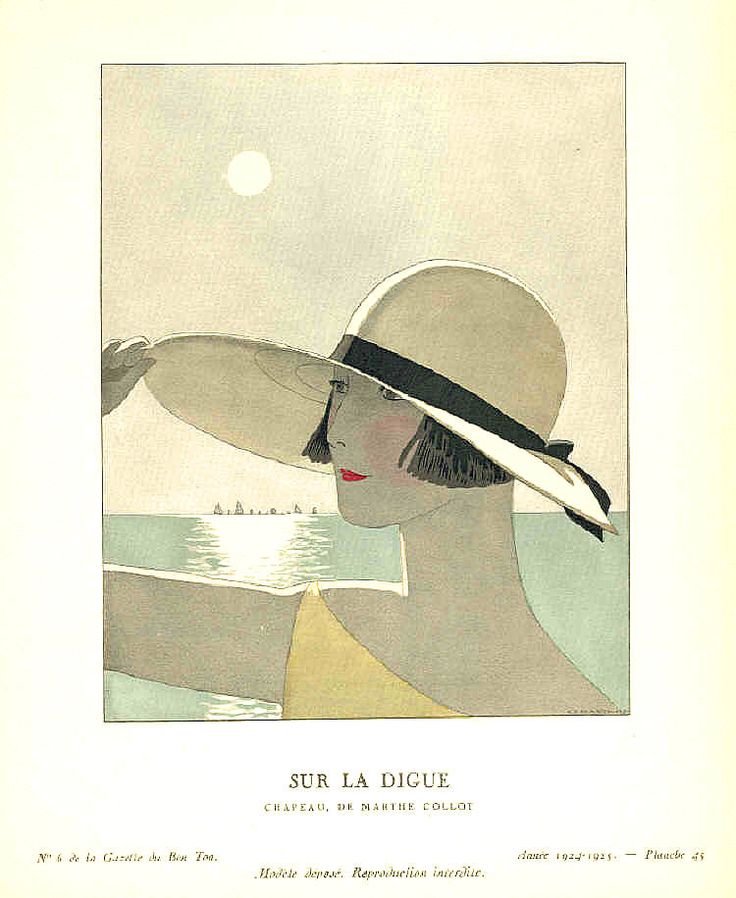

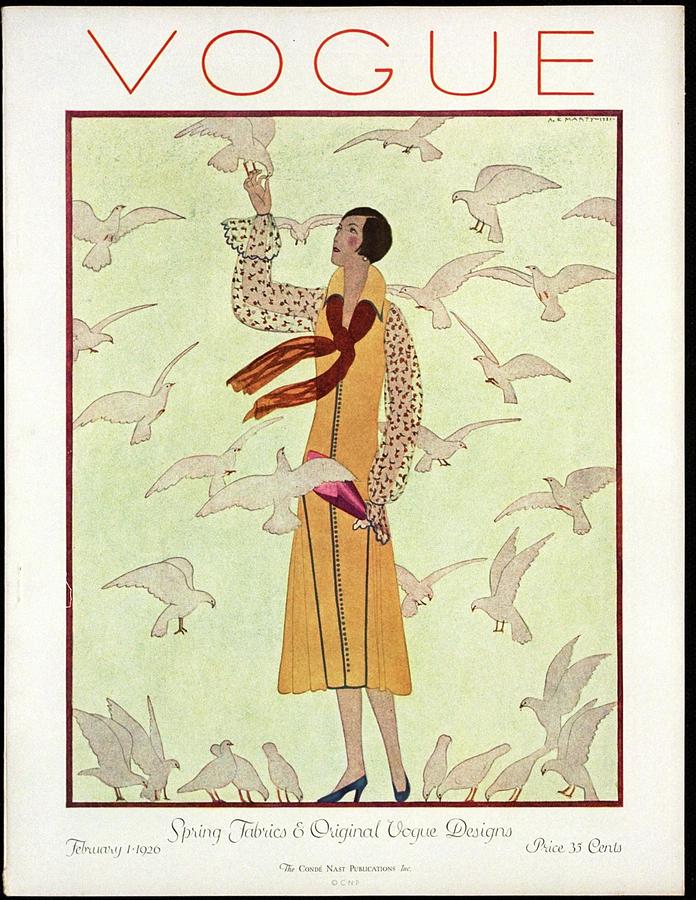

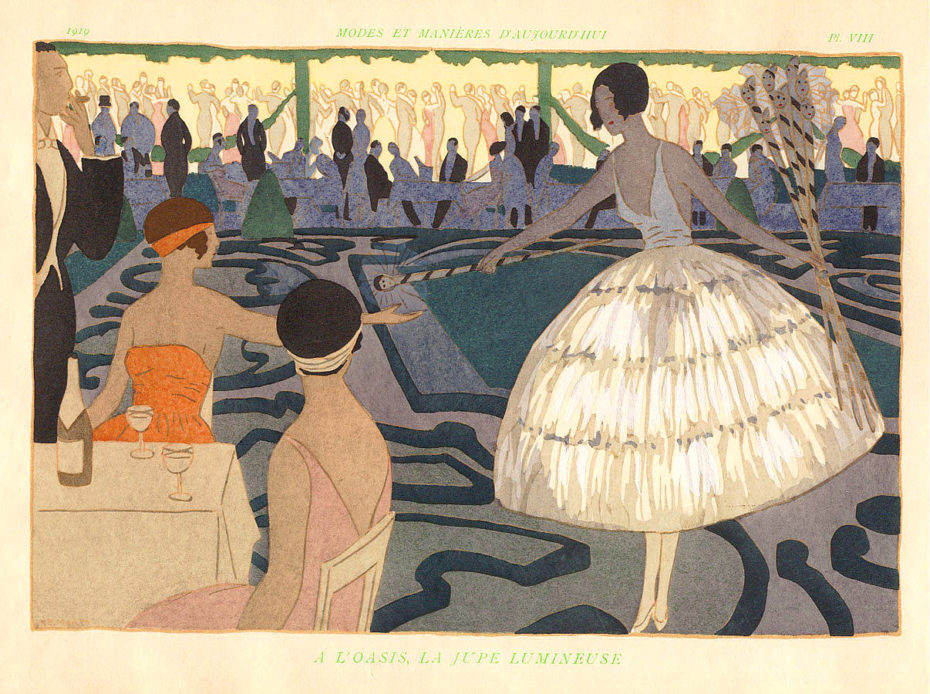

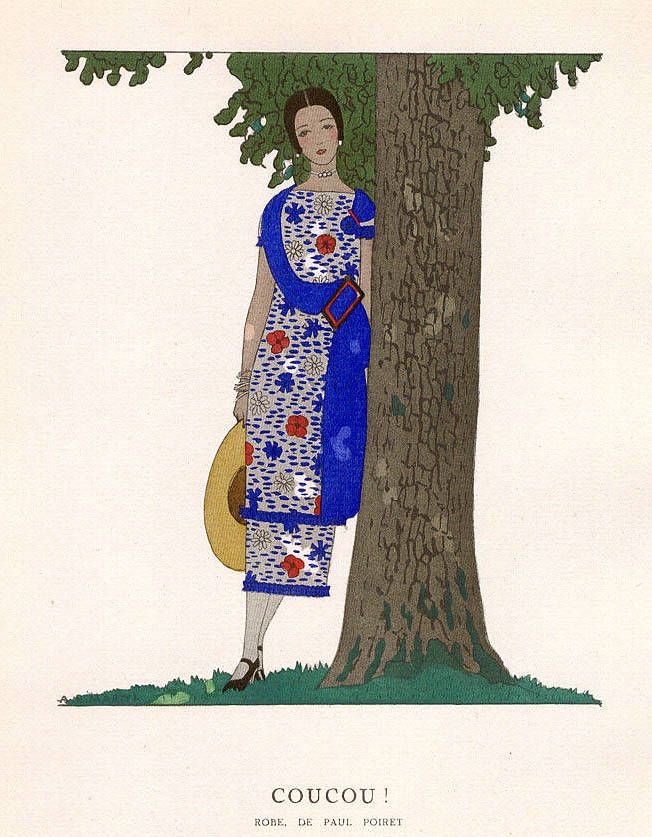

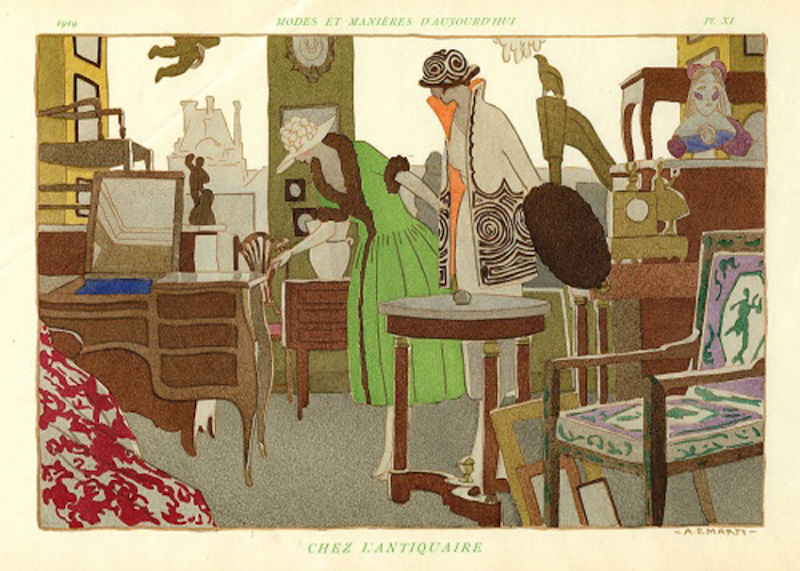

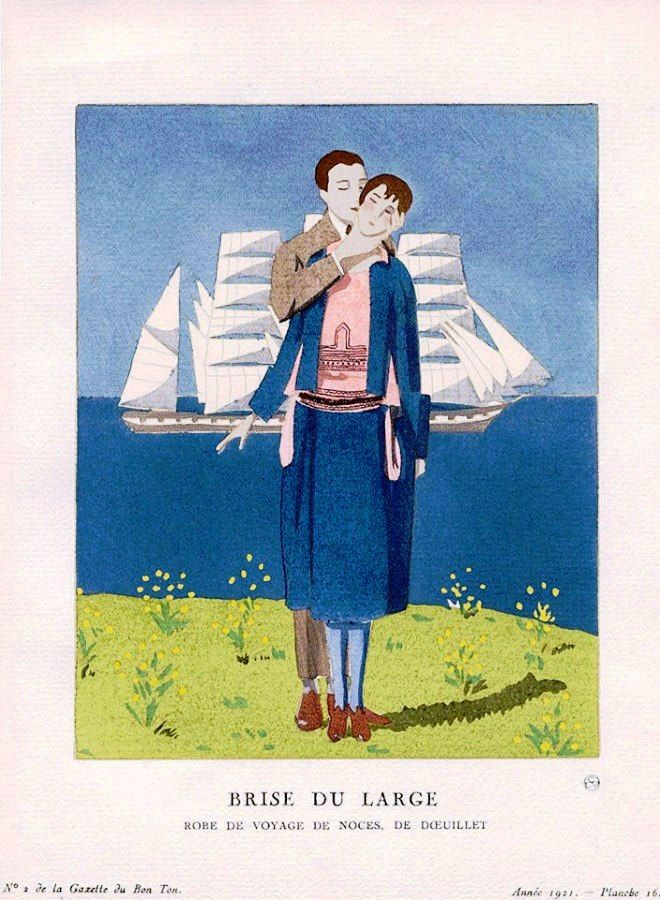

There was “an outpouring of luxury fashion publications that used pochoir” at the turn-of-the-century, explains Cassidy Zachary, author of Fashion and the Art of Pochoir: The Golden Age of Illustration in Paris. “This highly refined, painterly technique consists of applying layers of gouache paint or watercolor to achieve bold blocks of saturated color, [producing] works of visual artistry previously unrivalled in the history of fashion illustration.”

He studied at Paris’ Fine Arts School, and Montmartre’s Atelier Cormon, famous for fostering talents like Matisse, Soutine, Van Gogh, and others. He even served on the jury for the International Decorative and Industrial Arts Exposition in 1925, which was kind of the cradle for Art Deco.

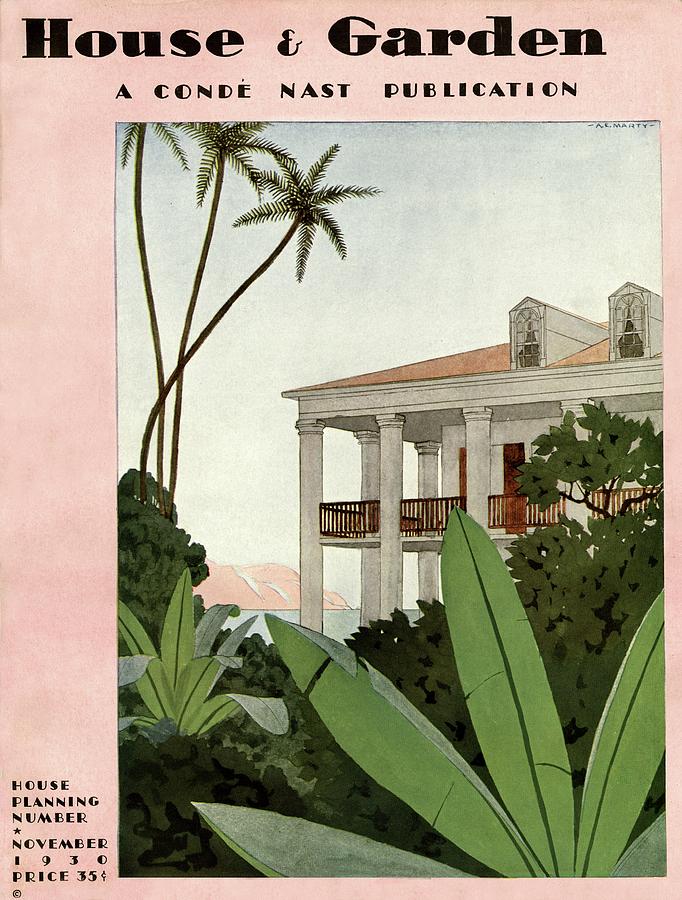

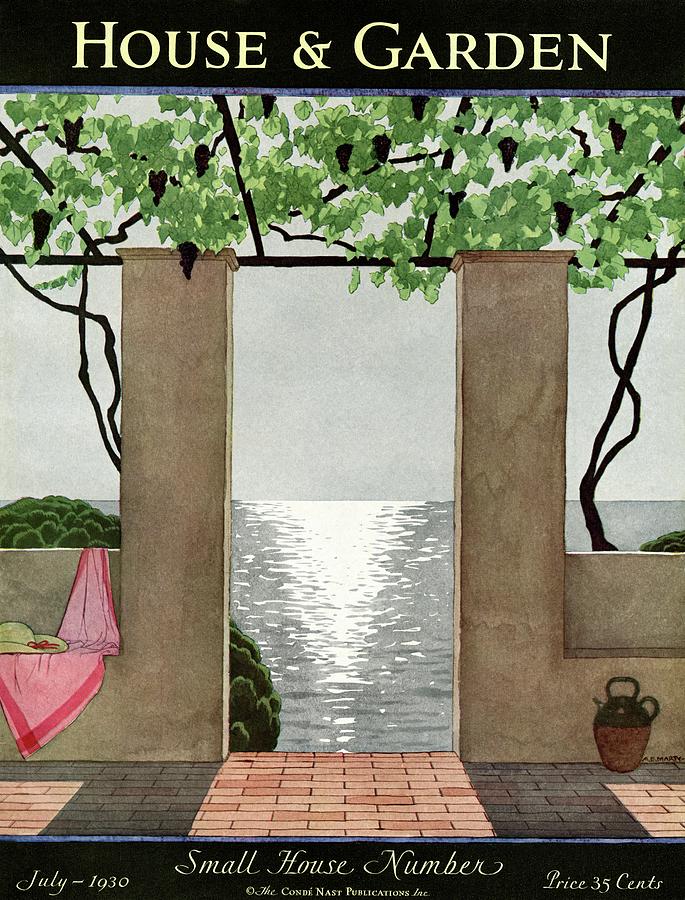

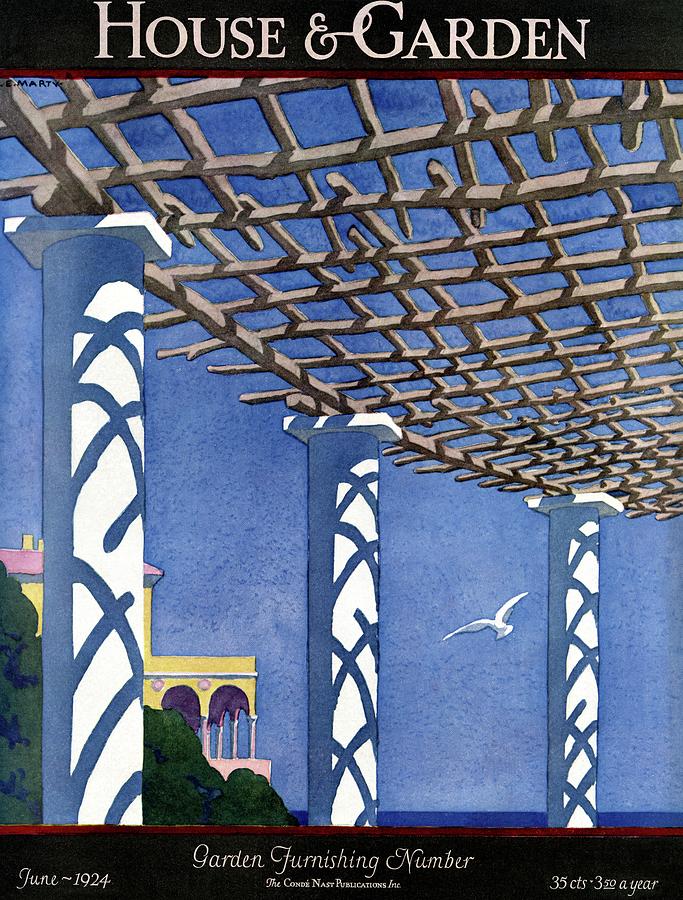

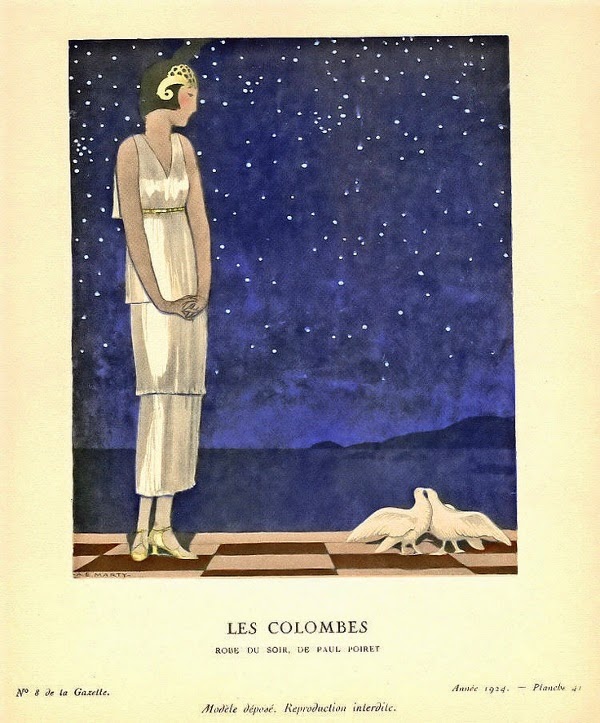

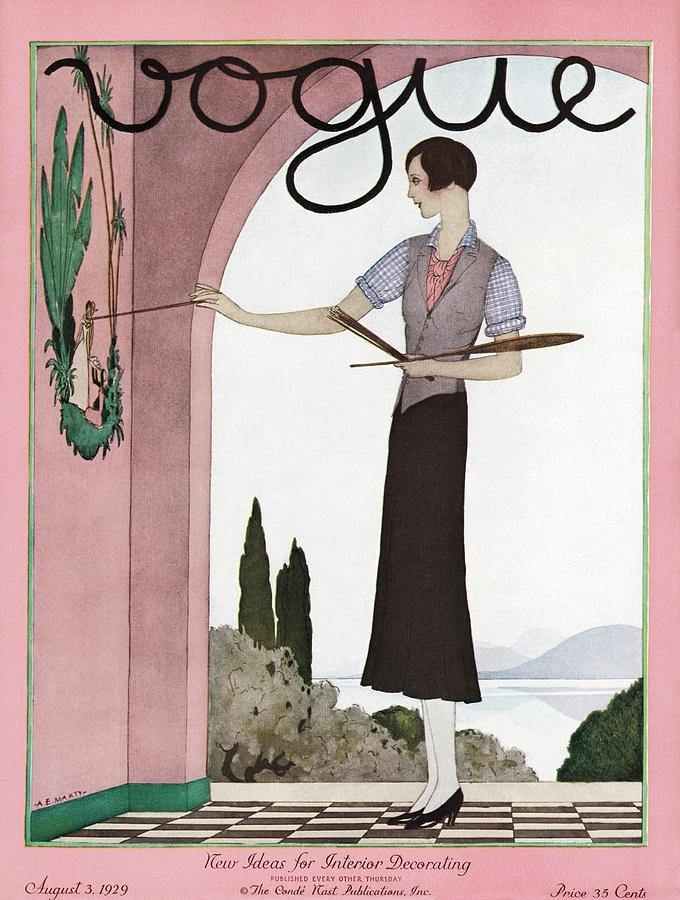

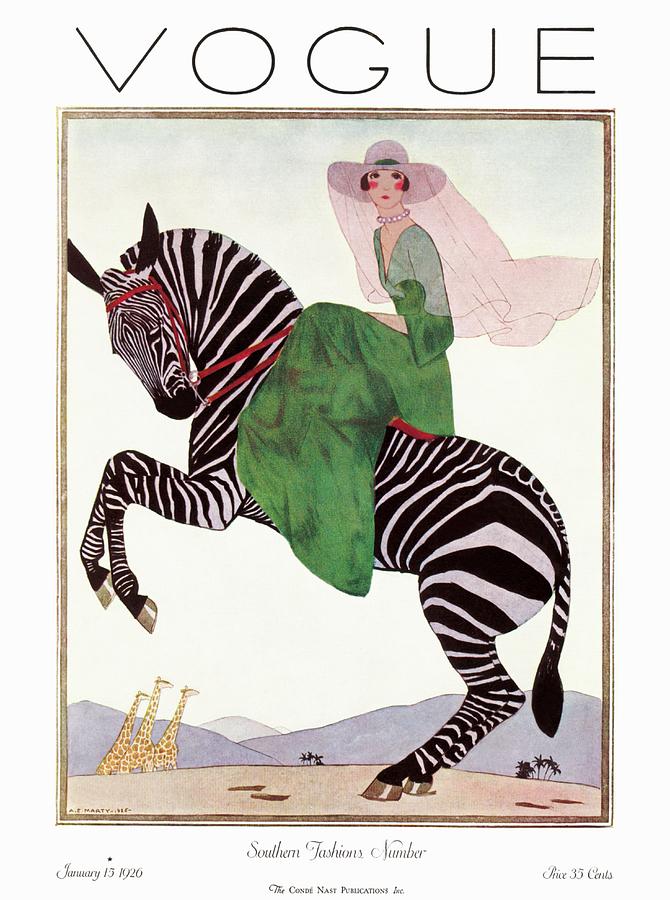

When it came to his illustration career, working with Vogue was just the tip of the iceberg. Marty was one of only four regularly contributing artists for the popular, pochoir Paris fashion magazine, La Gazette du bon Ton, and was regularly commissioned for pieces in Fémina, Vanity Fair, House & Garden, and even dabbled in costume and set design in the 1930s.

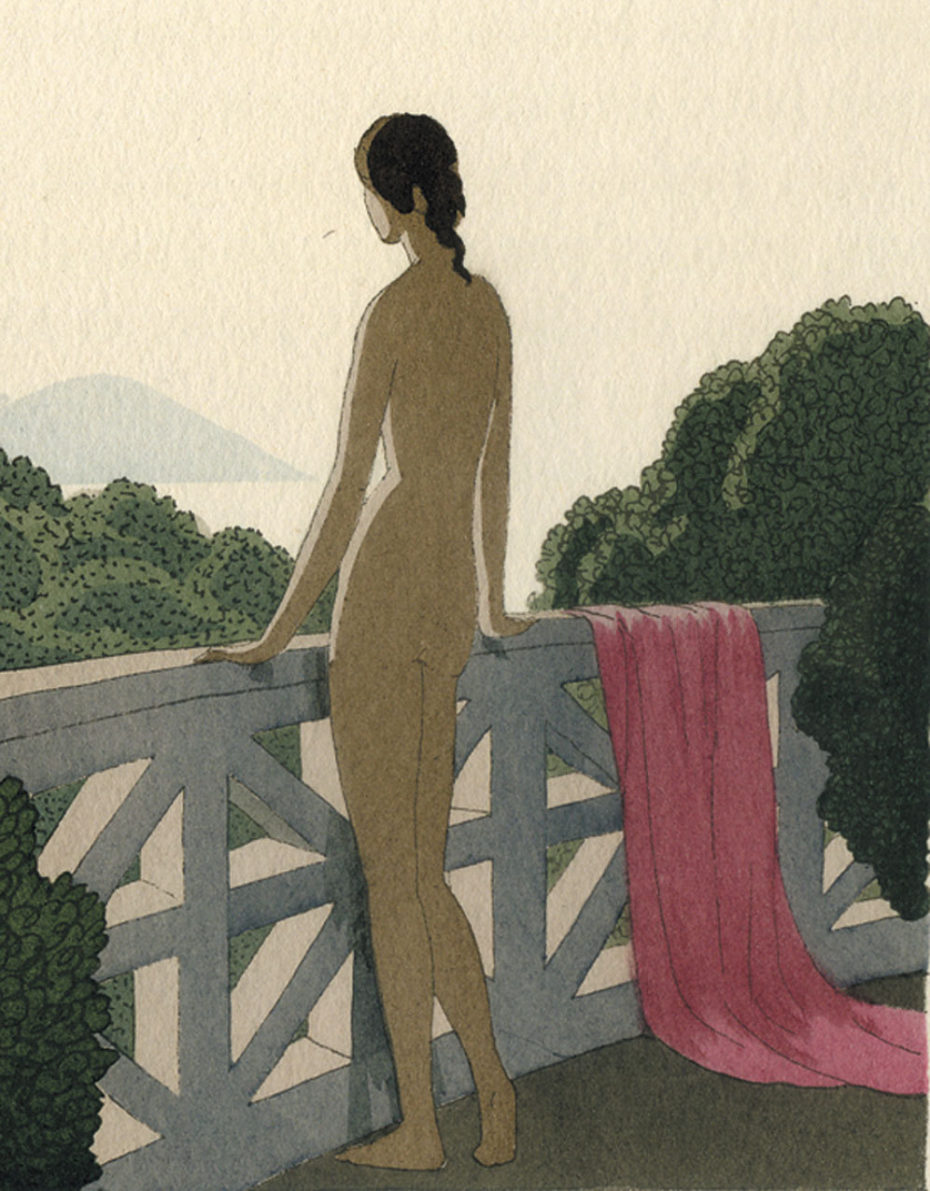

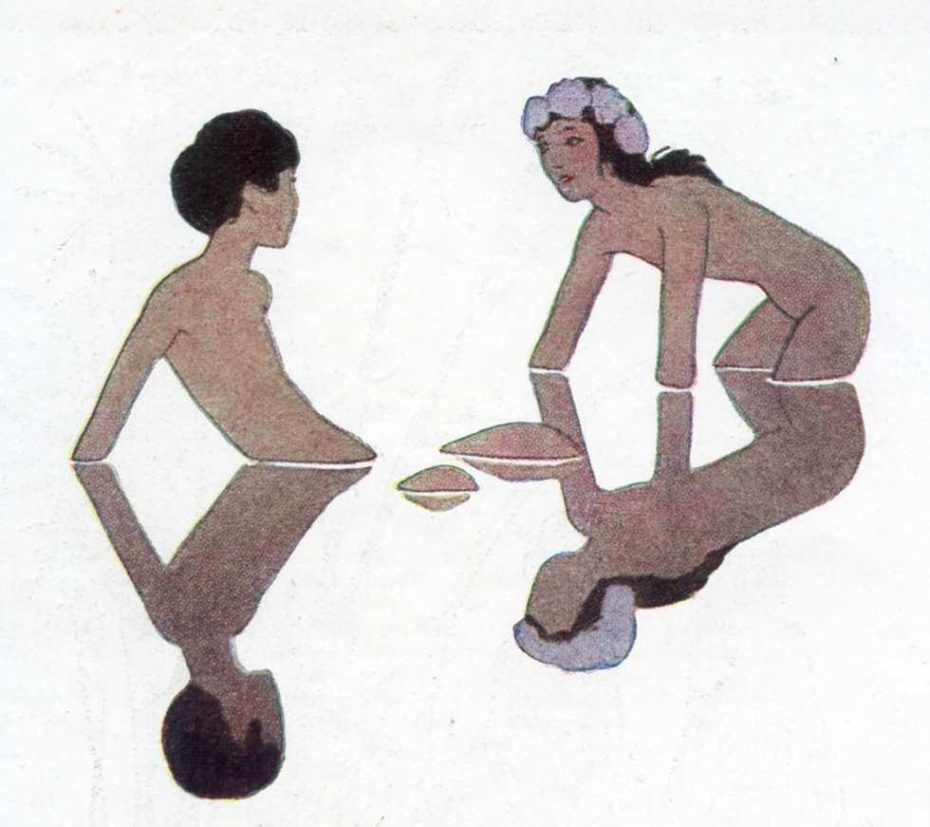

But this wasn’t just Art Deco. It was a dream world, and most importantly, one made accessible. Not everyone could afford a Dior frock, but almost everyone could fall into the romance of the pages of fashion zine for a few francs. And honestly, Mr. Marty’s art is still the perfect mini-vacation for your work-obsessed eyeballs.

The drawings are often sparse, and filled with pale sunlight…

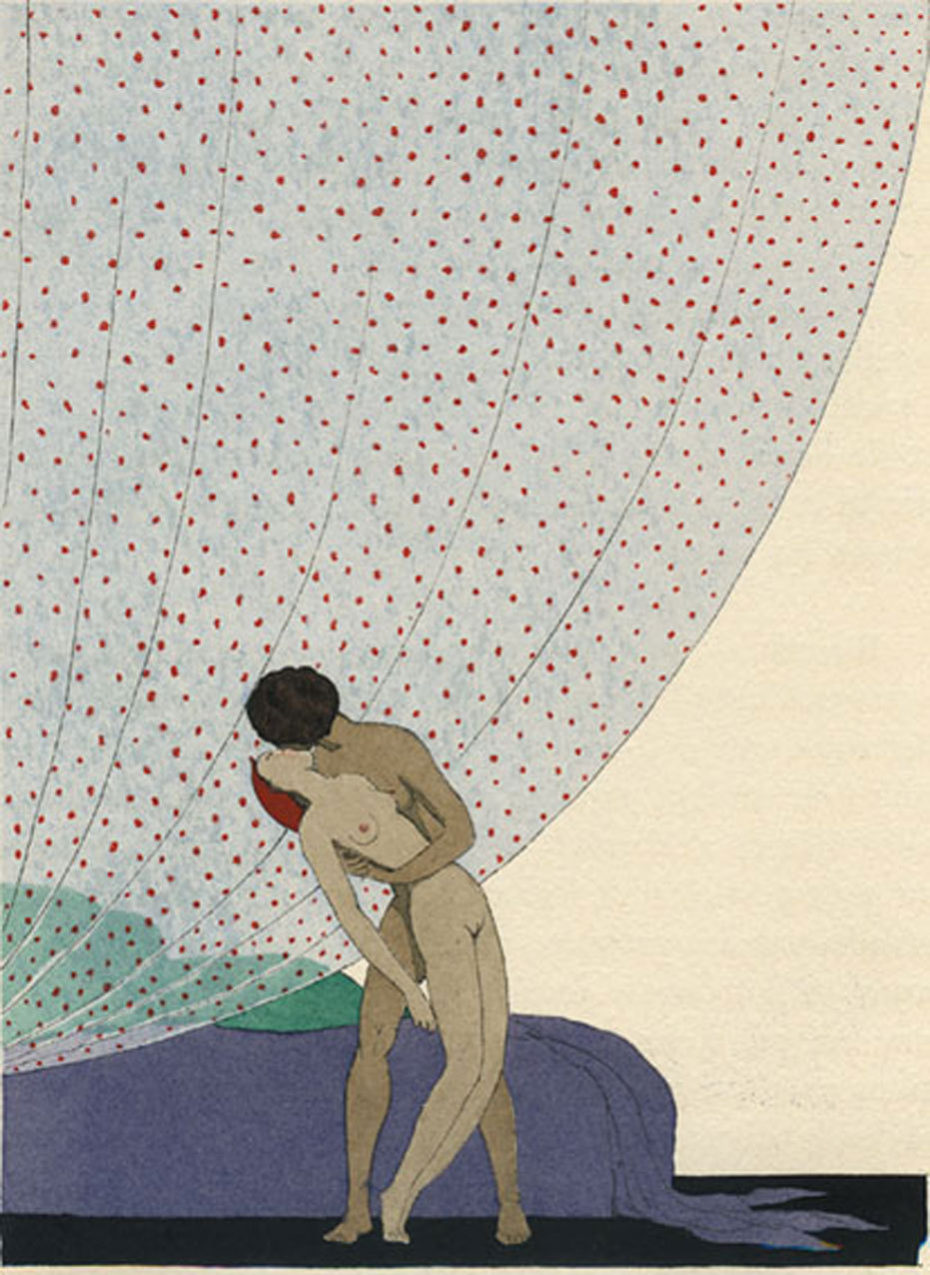

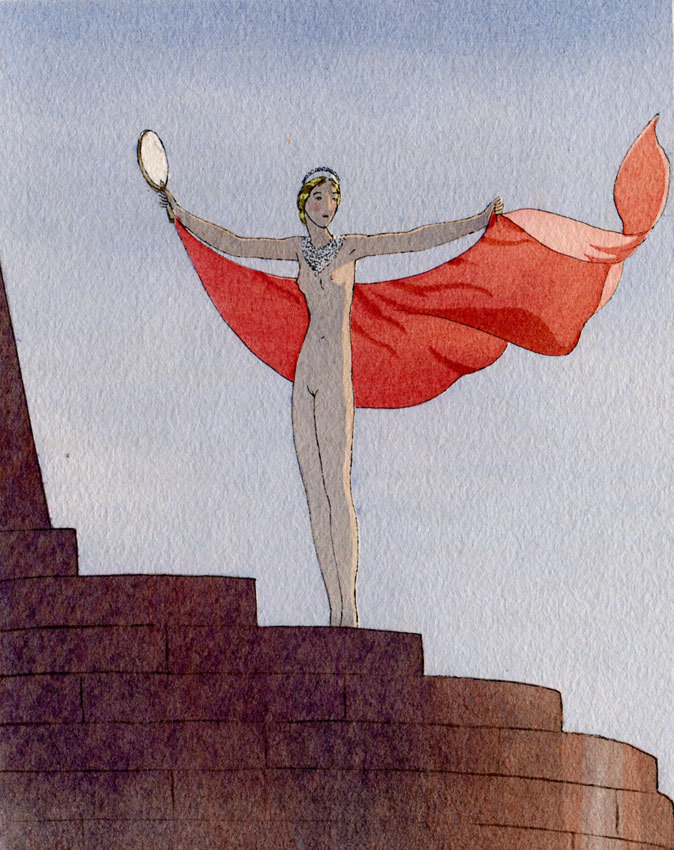

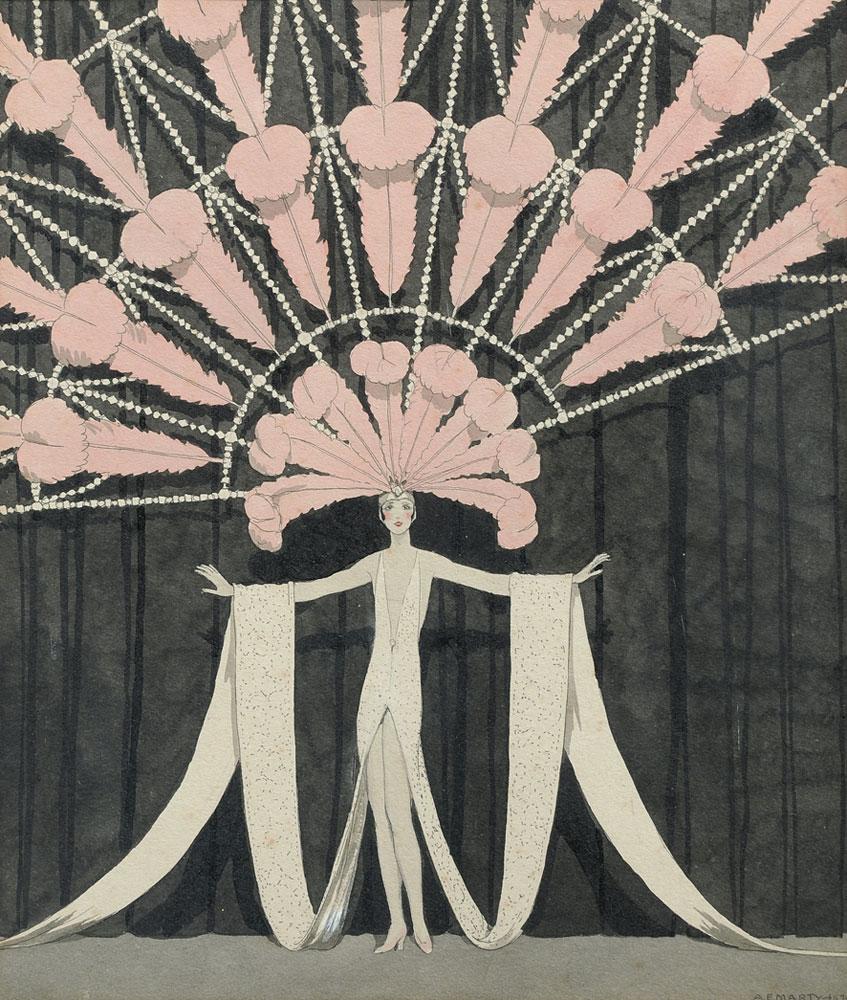

Or saturated with the deep blue and purples of, say, a parade on the night of Bastille Day, or a showgirl’s stage…

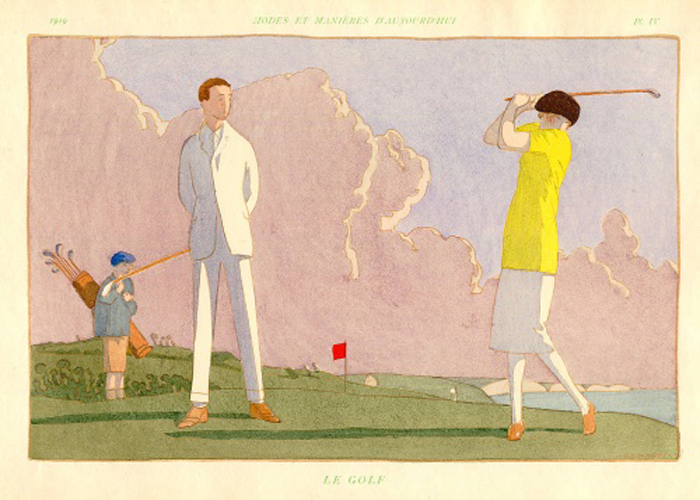

His swank-neck flappers are are both graceful and at the cutting edge of what it meant to be a modern woman (i.e. donning a Menswear-inspired vest! Playing golf! Riding a zebra, because why not!).

There was a cultural and social revolution underway, and the Flapper wasn’t just a symbol for fun, but female autonomy. In fact, she showed that the two went hand-in-hand. Marty’s only job was to capture that spirit as it was (fashionably) blossoming…