Every family has its black sheep. For the Bonaparte clan, it was Napoleon’s great grandniece, Princess Marie (1882-1962). She was not only a pioneer of psychoanalysis who actually saved Freud from the Nazis, but a staunch advocate for women’s sex research on some pretty taboo topics. You see, she was on a war path — a family trait, perhaps — to unlock the secrets of the vaginal orgasm.

She was born in the Parisian suburb of Saint-Cloud to Marie-Félix Blanc and Prince Roland Bonaparte, the latter of which was a descendant of Napoleon’s disinherited kid brother (seems she wasn’t the only black sheep). Her father’s family had lost nearly all of their fortune in the 1871 Paris Commune, and it wasn’t until he wed Marie-Félix, whose family owned most of Monaco, that real bank came back to the Bonapartes.

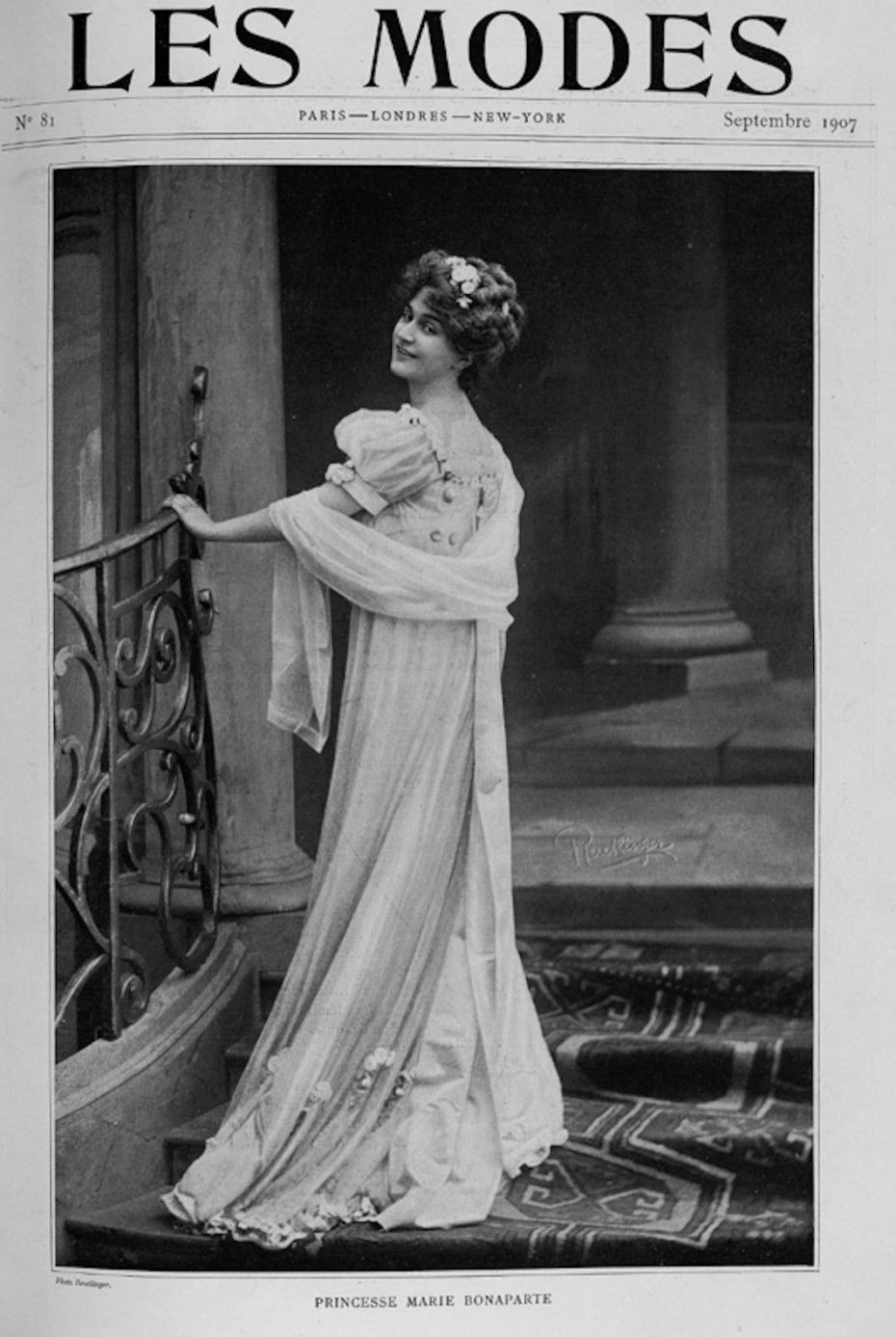

But it was hardly smooth sailing. Marie’s mother died in childbirth, and her hypochondriac grandmother shut her away from the world. So with no peers to play with and little room for socializing, she turned to her journal. “It is not surprising that she developed night terrors, morbid fears of illness and various obsessional anxieties,” explained NY Times journalist Anthony Sorr. By the age of seven, she’d filled five journals with what were essentially her first psychoanalytic observations. But by the age 16, she was in love and rather the It-girl:

Unfortunately, she was in love with her father’s black-mailing secretary, who didn’t reciprocate her feelings and threatened to publish her letters to him. Heartbreak ensued, and then, in a twist of fate, she found herself in an arranged marriage with Prince George of Greece, who was tall, handsome, kind — the total package.

But he was in love with his uncle Waldemar, which is a can of worms we just won’t open today. Regardless, Marie and George had a solid, albeit platonic marriage that lasted until his death.

Marie and George.

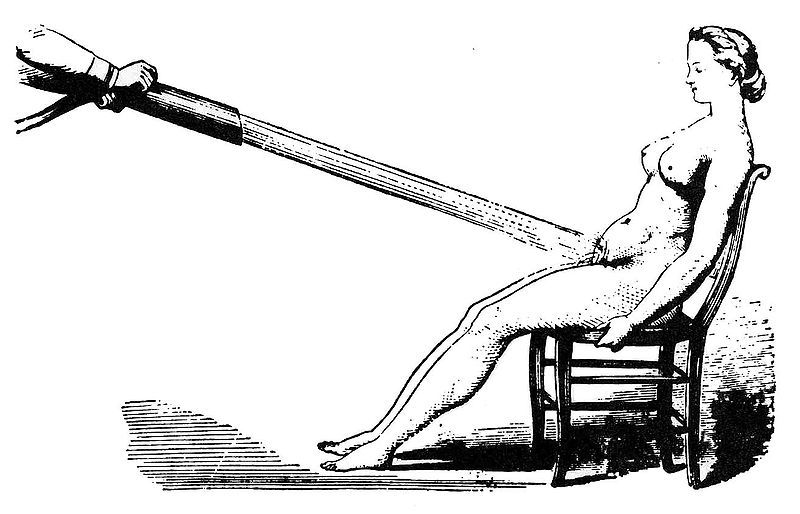

She started taking high-profile lovers like handlebar-stache donning French Prime Minister, Aristide Briand. There was only one problem: Marie couldn’t climax. The doctors classified it as frigidity, a term used to describe a female’s inability to respond to sexual stimulus, as closed the book. Why would a woman need to enjoy intercourse, after all?

It was the kind of orgasm that eluded Marie her entire life, and her quest to find it turned into an obsession linked with her own neuroses; she examined over 200 vaginas for her 1924 morphology study, “Considerations on Anatomical Causes of Female Frigidity”, and had three unsuccessful surgeries on her clitoris to try and cure her frigidity.

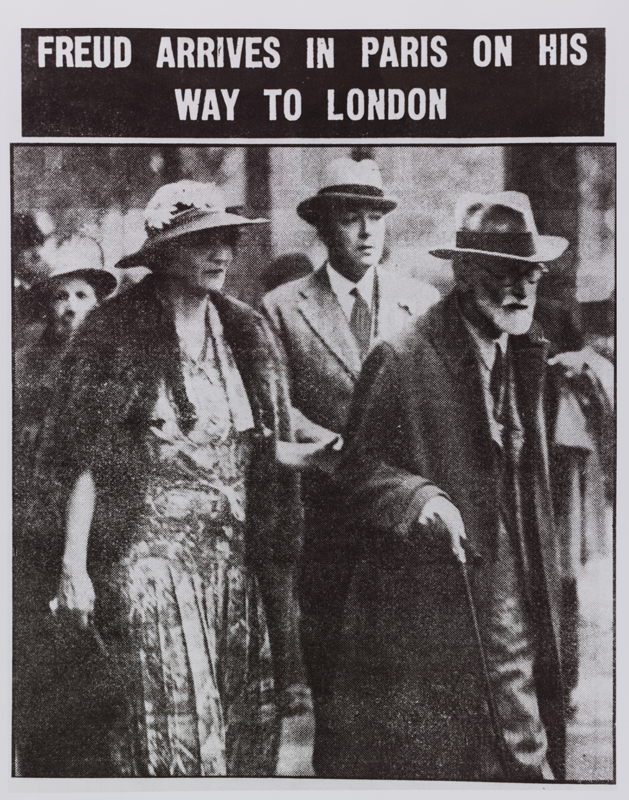

Martha Freud, Marie Bonaparte, William Bullit and Sigmund Freud. Arriving at Gare de l’Est, Paris, France, 5 June 1938

Enter Freud, who was serendipitously working on Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety when he met Marie in 1925. They became incredibly close friends and colleagues, with Freud dedicating two hours to Marie every day before work to analyse her own neuroses, as well as his.

“The great question that has never been answered,” he told her, “and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?'” In retrospect, and especially through a feminist lens, you couldn’t pick a more unlikely pair. But it worked.

Marie films Freud in his Vienna study.

Marie fell-in with the whole psychoanalytic scene, helping Freud’s work take off in France, and gaining fame in her own right despite publishing her research under the pseudonym, A. E. Narjani.

Marie with Freud in Vienna.

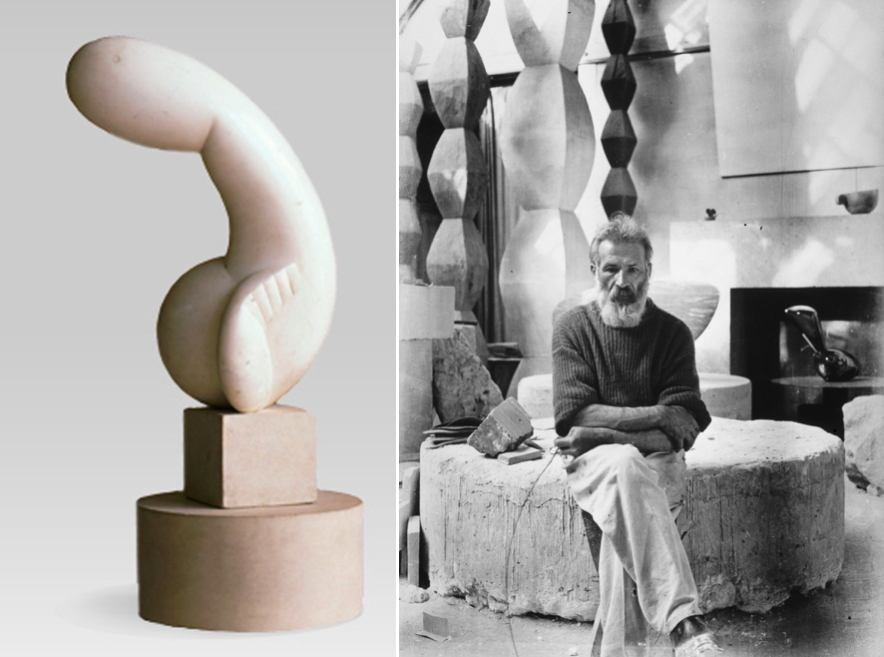

After all, how anonymous are you when an artist like Constantin Brâncuși makes a sculpture of you like this? He called it “Princess X”:

“Oh, she was a splendid old thing!” said one of Marie’s friends, the psychoanalyst J.C.M. Sym about the princess’s work. She was passionate, and curious. Once, when confronted by a flasher in Paris, she simply said, “Sit next to me and tell everything!” One has to admit, she does always seem to have a knowing smirk on her face…

And her work wasn’t limited to her own libido. She financed numerous scientific institutions, like L’Institut Pasteur, fought to abolish the Death Penalty in France, and saved about 200 Jews from death in WWII, along with her pal Freud. When the Nazis demanded a fat ransom to release him from England, Marie came running. As for her thoughts on her famous relative? “My great uncle, Napoleon, was the ultimate mass murderer” she wrote in her autobiography. “But I always had a thing for murderers, they are so interesting.”

If you want to learn even more about Marie, there’s a dramatic French biopic starring Catherine Deneuve in the title role. Here’s the scene in which she discusses her operation with her doctor: