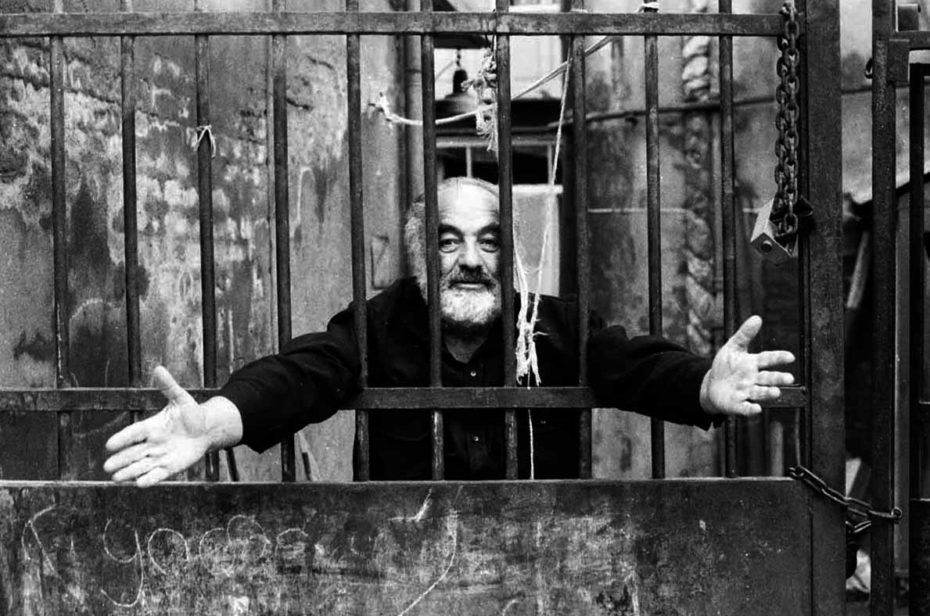

It was a pretty epic Round Table, albeit one held in vain. Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard, Yves-Saint Laurent and other creative power-houses had joined forces with one impossible goal: to save Sergei Parajanov. “In the temple of cinema, there are images, light and reality,” said Godard, “Sergei Parajanov was the master of that temple.”

Locked up by the Soviet government in a gulag and robbed of his ability to express himself, any cinephile today will tell you about the tragedy of the years the Georgian filmmaker spent behind bars for non-existent crimes. Most importantly, they’ll tell you about the defiant beauty made by the one they called, “the Madman”…

There’s little talking, and lots of eye candy. He invented his own cinematic style, charged with Surrealist symbolism and piercing gazes, and although Sergei studied film he insisted that one is either born a director, or not, and that “it’s not something you can learn”. It is, however, something you can hone.

The Georgia he grew up with was pulsing with cutting-edge art and culture, but that all changed when Russia took control in the 1920s. Parajanov held fast to his love of ornate Georgian traditions, particularly in pieces like Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors that played the fine line between collective memory, truth and ritual. Sound cryptic? That’s how you know it’s a Parajanov film.

Then there was the immense scale of his pictures, which were often filmed on sacred sites and filled with an eclectic cast, i.e. flocks, herds, and biblical pairs of animals. “A brilliant horse is acting in the film,” Parajanov said of a white stallion once. Scene stealers were everything from a room filled with sheep, to a towering wall of Persian rugs.

But his projects always ran against the new government’s grain. Nearly all of his film projects and plans from 1965 to 1973 were banned and the ones that did conform to Soviet censorship, Parajanov later disowned as “garbage”. They were by Parajanov, but without any of his spirit due to the limitations of Soviet Realism-approved dialogue and cinematography. It’s an inadvertent testimonial of just how suffocating the government was for artists who never had full creative control over their work.

In 1965, Parjanov broke with Soviet Realism and exploded onto the avant-garde scene with Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, a film influenced by Andrei Tarkovsky that turned him into a Surrealist darling and unexpected figurehead for the Ukranian Nationalists. They saw it as a love letter to their once free country. His work was banned, and had to be smuggled into Western Europe.

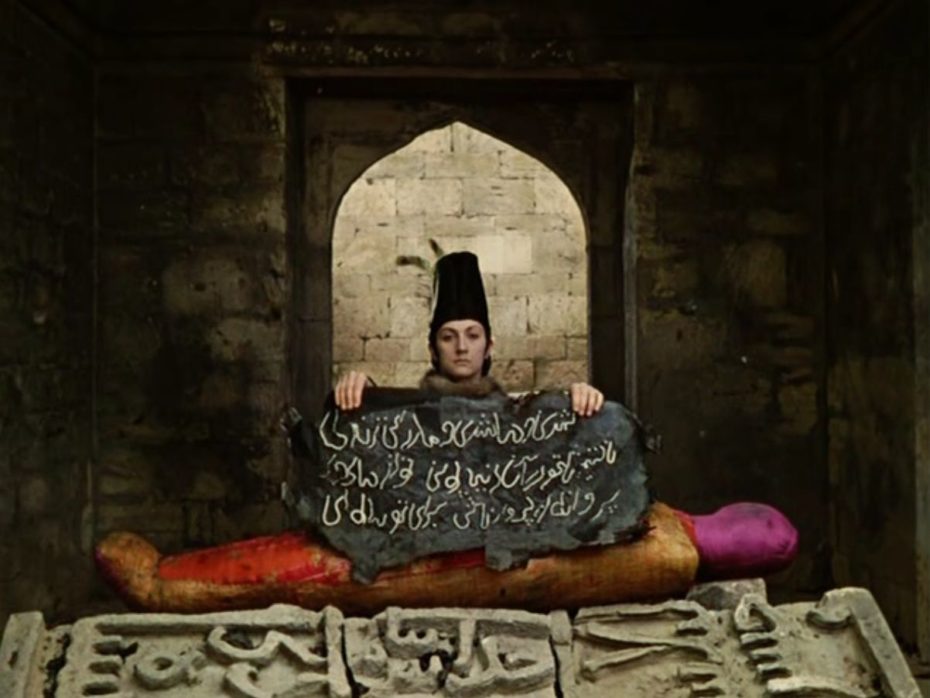

The year 1969 was the boiling point. The film now considered his masterpiece, The Colour of Pomegranates looked tame on paper as a biopic of 18th century Armenian poet Sayat-Nova — but in reality, it celebrates the survival of Armenian culture in the teeth of oppression and persecution.

“There are specific images that are highly charged — blood-red juice spilling from a cut pomegranate into a cloth and forming a stain in the shape of the boundaries of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia,” writes film critic, Frank Williams.

You feel as if you’ve stepped into the old masters paintings at the Louvre.

By the early 1970s, the Soviet authorities had grown increasingly suspicious of Sergei and his “inflammatory” movies. That he was bisexual did not help him find favour with the Soviets either. In 1973, he was wrongfully sentenced to five years in a Siberian labour camp for the “a rape of a Communist Party member, and the propagation of pornography”. During this time, it’s said he made about 800 works of art out of anything he could find—dolls, drawings, sculptures — which were taken and destroyed by guards who called him mad, save one guard who only said, “the director is very talented”. In reality, his incarceration was meant to send a brutal message to the Ukranian nationalists who loved him…

Even when he was released, Parajanov was “silenced”, as he said. He tried to get back on his movie making, but struggled for another ten years until the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1980s. When he died in 1990 at only 66, he left his final work unfinished, leaving the world to wonder what other visions of his were lost to time.

Luckily for us, there’s a Parajanov museum in Armenia that’s not only a moving tribute, but seriously gorgeous:

And last but not least, his films. Watch the trailer for The Colour of Pomegranates below: