We thought we’d heard it all when it came to imposters. Clearly, we hadn’t met Pierre Louÿs. The French writer had Europe’s literary scene eating out of the palm of his hand, and was decorated as a Chevalier and Officier de la Légion d’honneur in his lifetime, two of his country’s highest honours, that would never have been awarded to him if it weren’t for one larger-than-life lie– Pierre’s ancient Greek, lesbian-erotica poet who never existed.

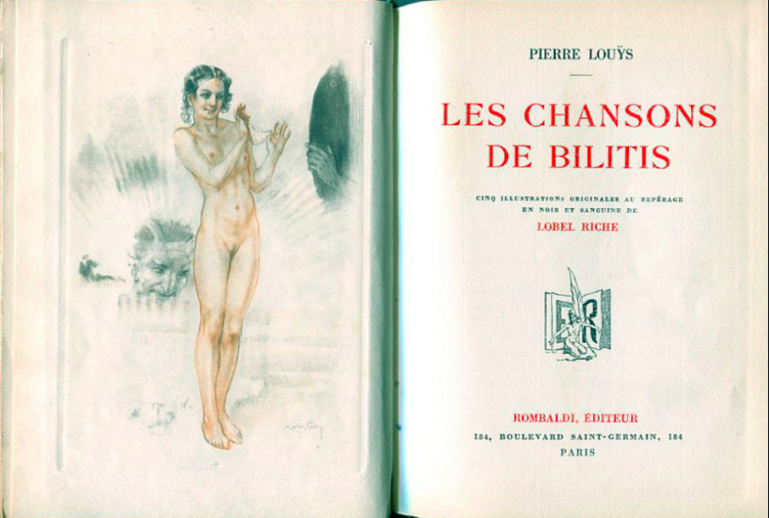

It was a lie well-catered to a literary crowd obsessed with antiquity. Louÿs claimed to have translated the newly discovered, erotic memoirs of Bilitis, a disciple of the ancient Greek poet Sappho, and published them in 1895 as Les Chansons de Bilitis (The Songs of Bilitis). He said she’d scrawled them on a cave wall in the 6th century, and that all he had to do was translate…

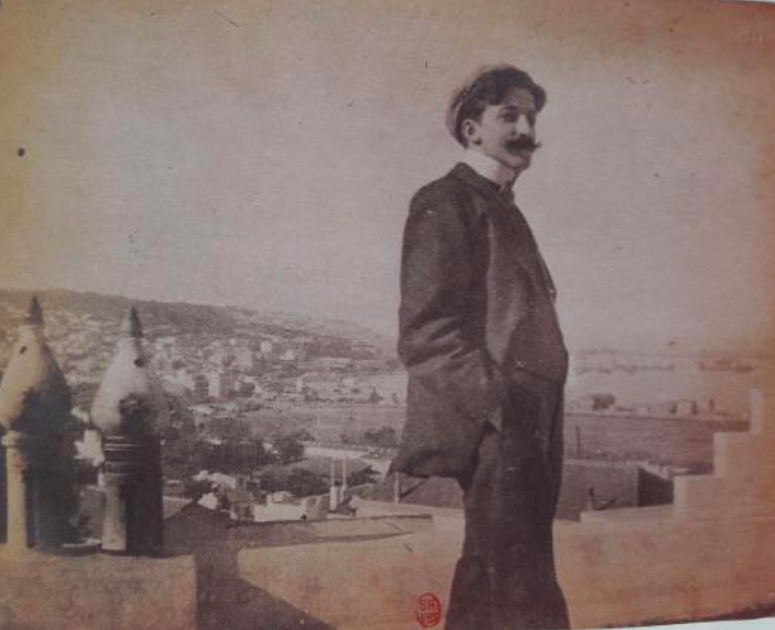

Louÿs was what you could call an expert amateur academic. Born in Belgium as Pierre-Félix Louis, he moved to Paris to attend the ridiculously exclusive l’École Alsacienne. By 1890, he’d started spelling his name “Louÿs” in a nod to his love for classical Greek literature (the letter Y is pronounced in French as i grec, or “Greek I”) — so his nom de plume was a bit of a give away in itself. He was a voracious reader, spoke several languages, and beefed up Bilitis’ credibility with a bibliography of ancient fake sources. He even claimed to know the exact location of the cave in which his “archeologist friend” discovered the writings. It sold like hot-cakes.

Oscar Wilde became a friend and fan, as did André Gide, Claude Debussy, and the Who’s-Who of Paris’ edgy art scene. And perhaps that’s why Louÿs willingly debunked his hoax not long after its release. It wasn’t enough to be merely the translator.

When he revealed himself as Bilitis, he was miraculously met with little reprimand. Why? According to scholar André Guyaux of the Sorbonne, Bilitis was never really written for women. “For anyone with a serious academic eye,” said Guyaux, “it was clear these were written through Louÿs’ perception of the lesbian gaze for him and his friends”. The character of Bilitis was a hybrid of women fetishised by Louÿs, like the Algerian woman Meryem mentioned in the dedication, and the enigmatic Zohra Ben Brahim:

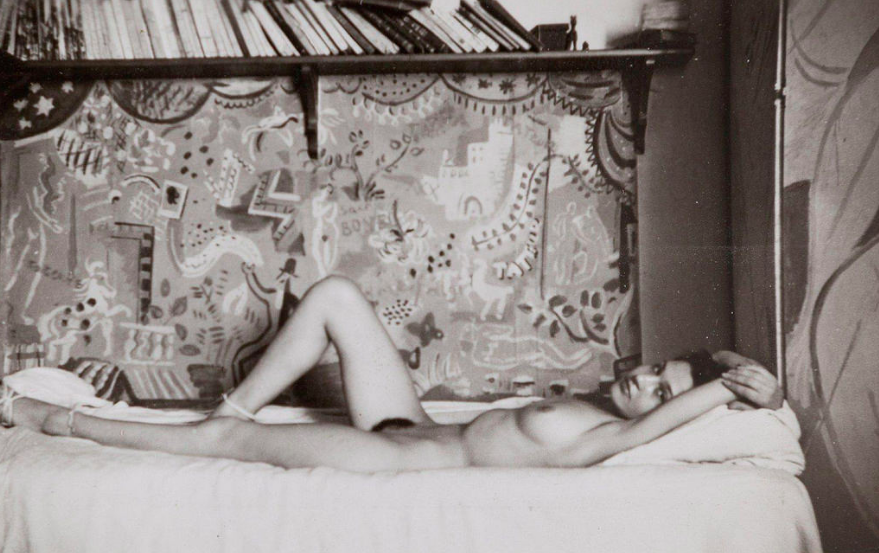

Brahim was especially close to Louÿs and Debussy, and eventually travelled to Paris with Pierre. What little we know about Brahim exists through the very problematic, exoticised accounts of Louÿs, who boasted that he took over 100 photographs of his ” little savage.”

“Zohra’s unashamed sensuality and her freedom from sexual hypocrisy formed…a pleasing contrast with the puritanical, and in Louÿs’ opinion, perverse moral code which governed French society,” explained scholar Jean-Paul Goujon. And ironically, even though Louÿs thought women would never read his work due to their “modesty of words and concern with appearing respectable”, Bilitis was soon reclaimed by womens groups and lesbian communities for their own self-empowerment.

LBTQ advocate and creative Natalie Clifford Barney, whose magical Parisian salon is worth another article entirely, genuinely saw herself in Bilitis and said the poems inspired her to create her own Sapphic writings. The United States’ very first lesbian civil and political rights organisation, the Daughters of Bilitis, also declared the text its opus.

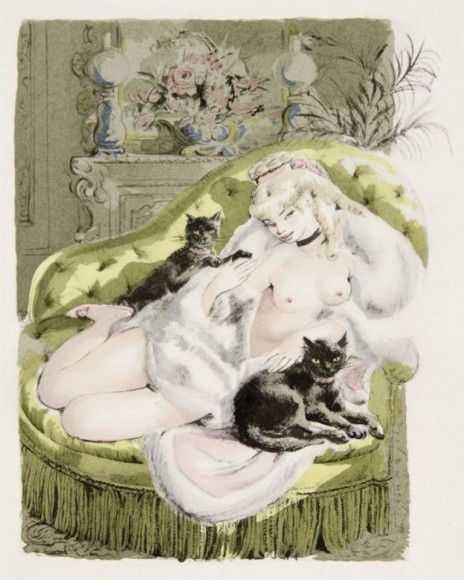

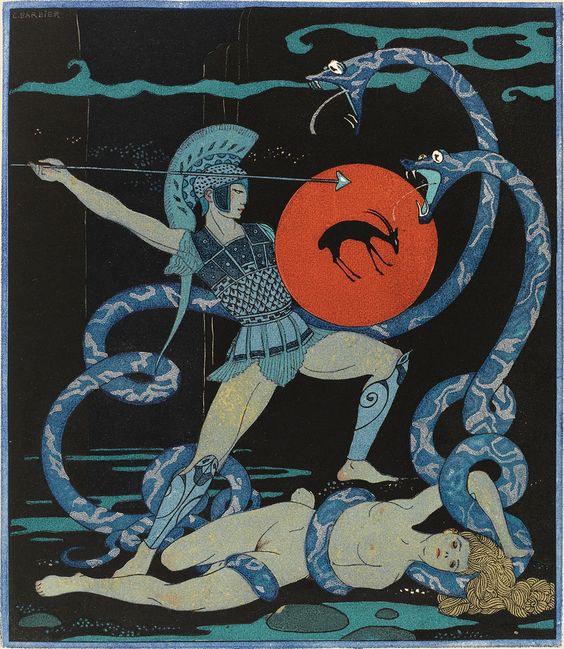

And that’s how Bilitis’ legacy was cleverly superseded by countless other works by creatives, like the Parisian erotica illustrator Suzanne Ballivet, a raunchy (and largely unrepresented) artist who’s still going to this day:

“The style itself is amateur…the structure, tone, everything” says Guyaux about Bilitis. With lines like, “she opened her tunic and tendered me her breasts, warm and sweet, just as one offers the goddess a pair of living turtle-doves,” we see his point.

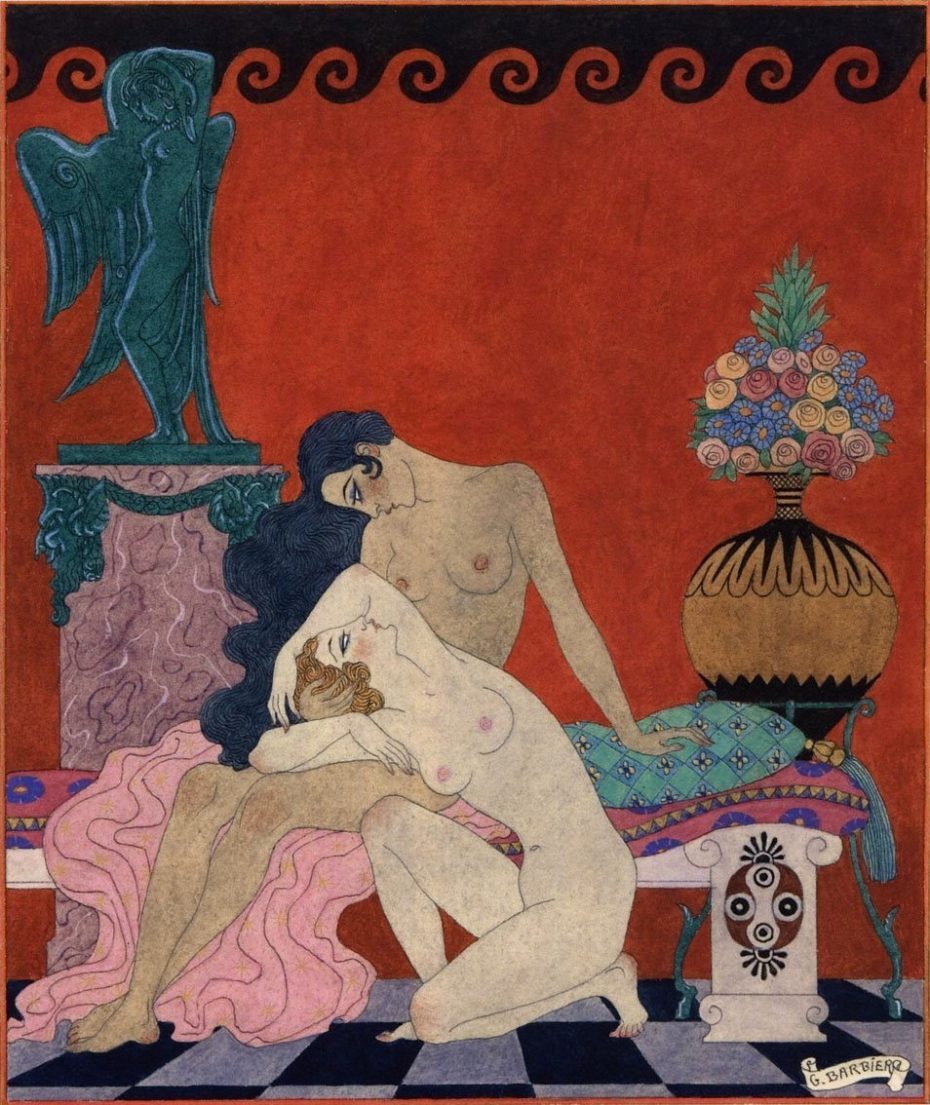

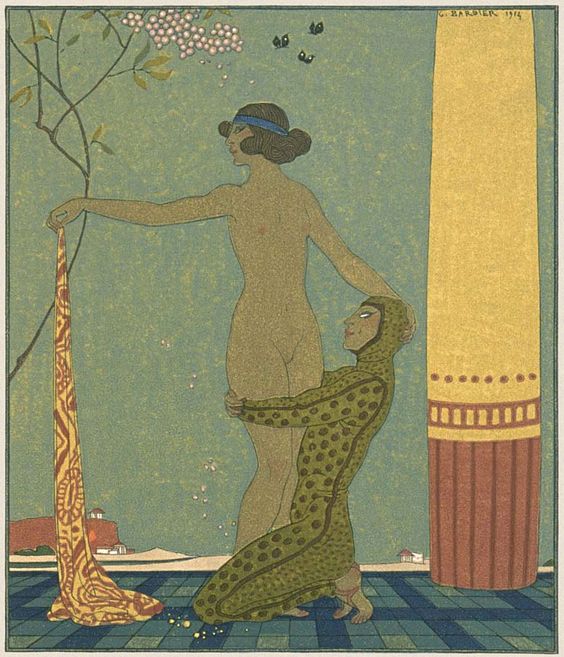

It’s solid smut. “At the very least,” ads Guyaux, “we got pieces of Debussy out of it.” Sure enough, he composed some lovely works for his friend’s poems, which also inspired illustrations by George Barbier, Foujita, A.E. Marty, and others…

Even though Bilitis was never a real person, you could argue that she existed through the eyes of the artists and advocates who took her story to heart — and then made it into a better one.