Without them, Paris would’ve stood still. They were immortalised in song by Serge Gainsbourg, and put into poetry by the cheeky Raymond Queneau. But by 1975, Paris’ metro ticket punchers, or poinçonneurs, were a dying breed. Their rise and fall traces the streamlining of the whole métropolitan system, which was inaugurated at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair to a crowd in awe — but mostly, relief. The population was bursting at its seams, and the lack of easy transport was driving Parisians mad…

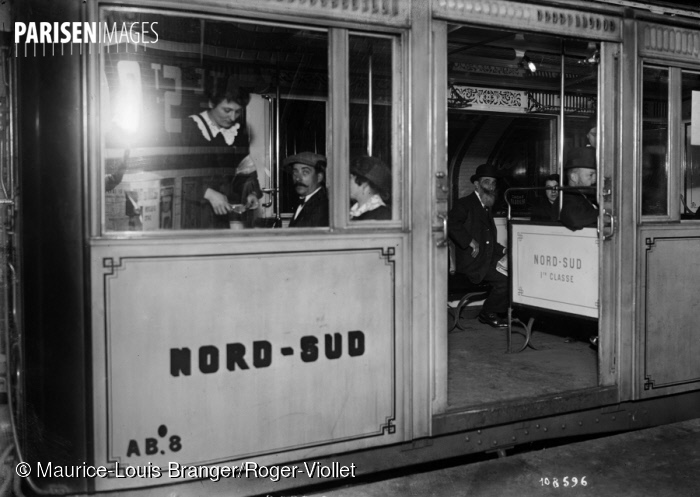

The Line 1: Porte Maillot–Porte de Vincennes was the first to open its First and Second Class car doors to the public (yup, that class segregation went on until 1982), and sold 30,000 tickets in its first day. The poinçonneurs were kind of the gatekeepers to those precious seats, situated in their little kiosks deep underground.

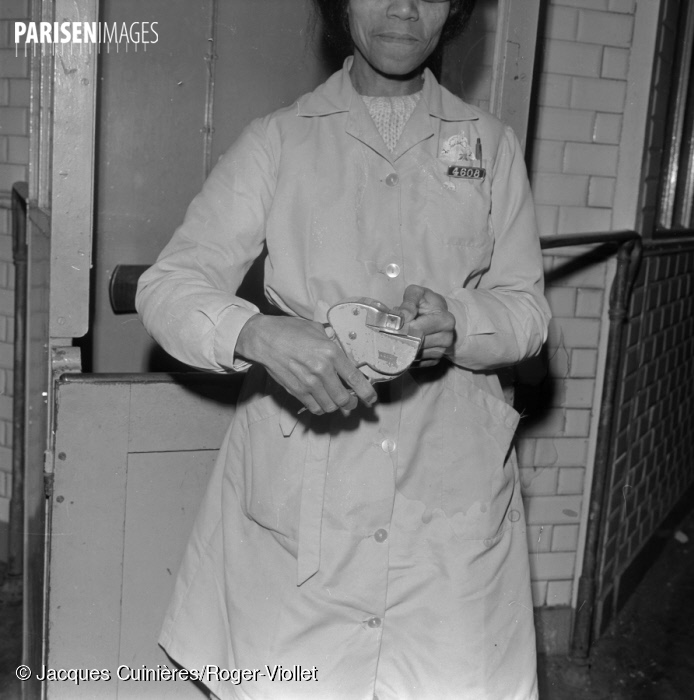

Ticket-puncher in a subway. Paris, in January 1947.

They weren’t all men, either; as the war unfolded, more and more women went to work:

Ticket-puncher in the Paris Metro (or Metropolitain), January 1947.

World War I. Woman working as a ticket-puncher in the Paris Metro (or Metropolitain).

World War One. Woman working as a ticket-puncher in the subway. Paris.

Ticket-puncher of the Paris Metro (or Metropolitain), 1960’s.

If you take the metro today, keep an eye out for the boarded up little kiosks, which sometimes looked quite cute with their pastel hues and windows:

Other times, not so much:

We can understand why Gainsbourg wrote his now beloved French ditty, Le Poinçonneur de Lilas (“The Lilas Ticket Puncher” in referance to the line 3 of the métro) in 1958. “I’m the Lilas ticket puncher,” he sings, “The guy you cross paths with but never look in the eyes. There’s no sun underground. To kill the time, I’ve got in my vest, a few excerpts of Reader’s Digest/ In that book it says that folks sit back, relax, and head to Miami, while I’m working like a slave at the bottom of the cave/ They say all work is good work, but I punch holes in tickets. I punch holes, little holes, always more little holes.” It was an instant hit not just because it was catchy, but because it was so darn relatable for anyone stuck working when they’d rather be on a slow boat to somewhere sunny…

We’ll leave you with a babyfaced Gainsbourg pretending to be a poinçonneur for his track, ankle-deep in ticket punches: