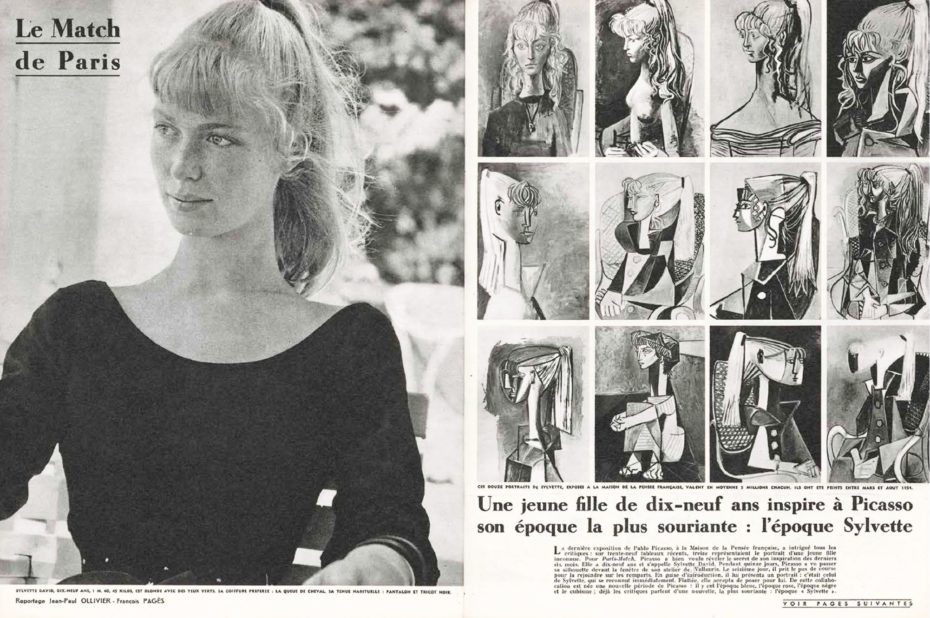

For a few Spring months in 1954, a melancholy Picasso found himself enraptured by 19-year-old Sylvette David. Of all the muses who bookmarked his life — and there were many — she’s fallen to the wayside of history as one of the most enigmatic and misunderstood. For years, critics wrote the body of work she inspired that summer as a footnote in the artist’s career. Yet the volume of pieces he made in homage to Sylvette, and her signature ponytail, was unmatched by any other woman in the artist’s lifetime. So who was Sylvette? And what made Picasso choose her over Brigitte Bardot? (True story).

AUCTION ALERT! At the end of 1954, Picasso gave Sylvette a 1954 copy of the Parisian art magazine Verve, which he signed and dedicated to her. The magazine, together with a ceramic bowl by Picasso and a selection of photographs by Villers and Edward Quinn from this period, will be offered in the Picasso Ceramics online sale at CHRISTIE’S until 1 July 2024. Sylvette David, now Lydia Corbett, has been a practicing artist since the 1980s. The sale will also present two of her original paintings, at auction for the first time.

The French Sylvette, now 83 and going by the name “Lydia Corbett” (but more on that later), came from arty stock. Her mother was an oil painter, and her father, an art dealer. “As a small child, she grew up free on a naturist island, Île du Levant, off the southern coast of France, moving during the war to a safe enclave in the eastern mountains,” reads her official site.

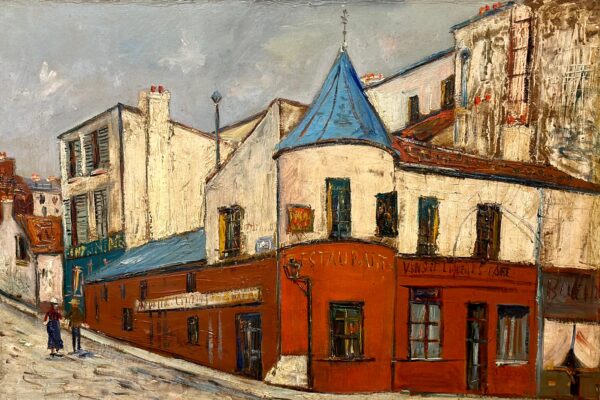

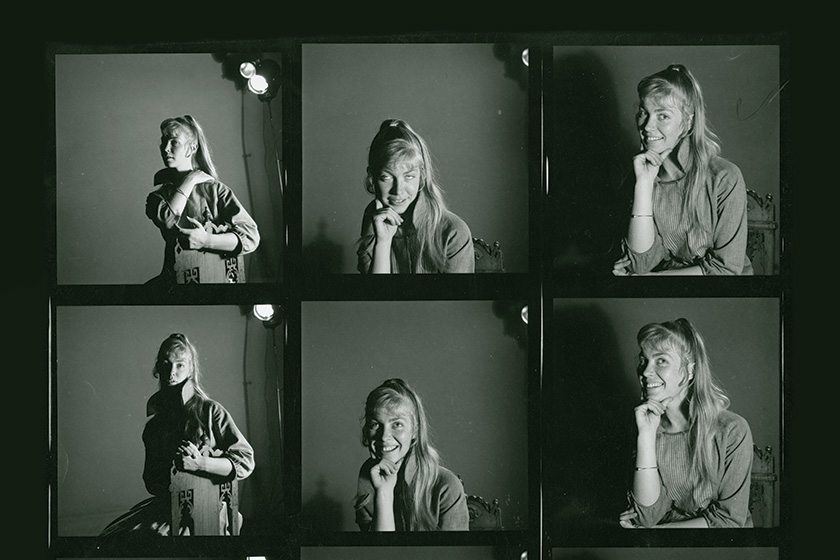

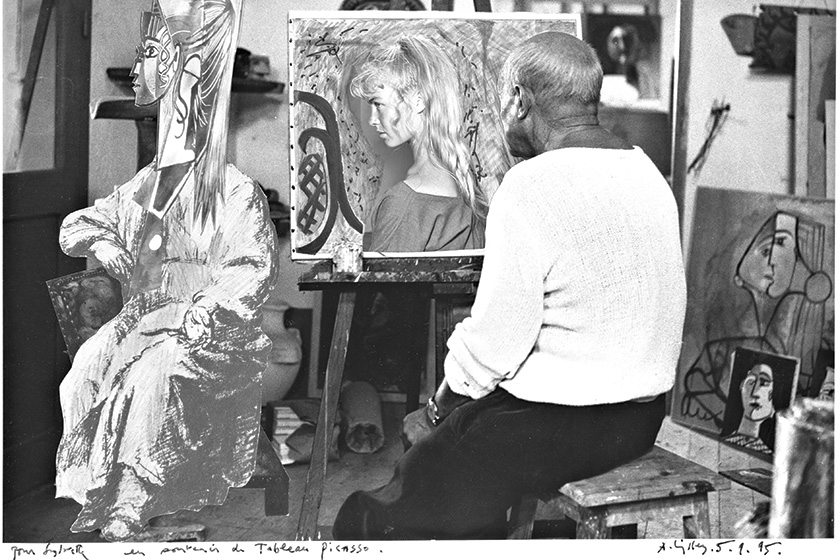

At one point she was living in a town called Vallauris on the Côte d’Azur with her fiancé, Toby Jellinek, who took many of these photographs. In other words, Picasso’s neck of the woods.

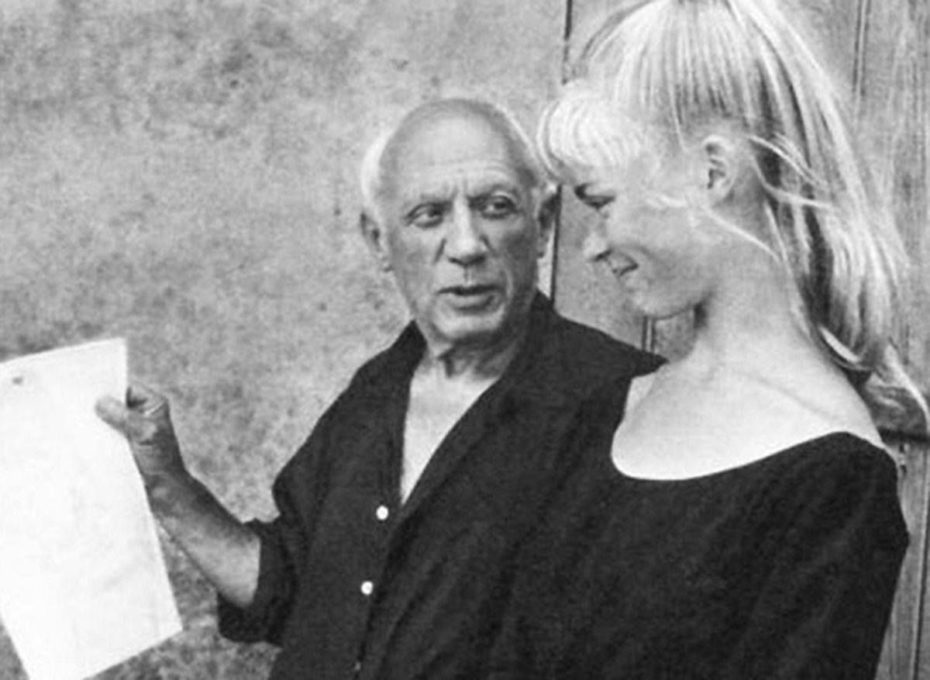

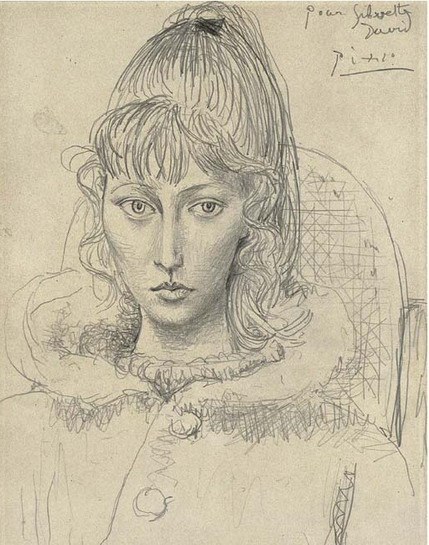

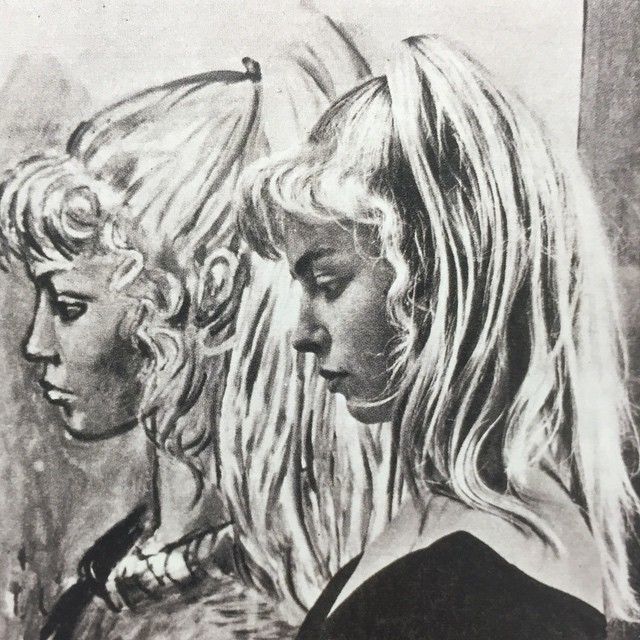

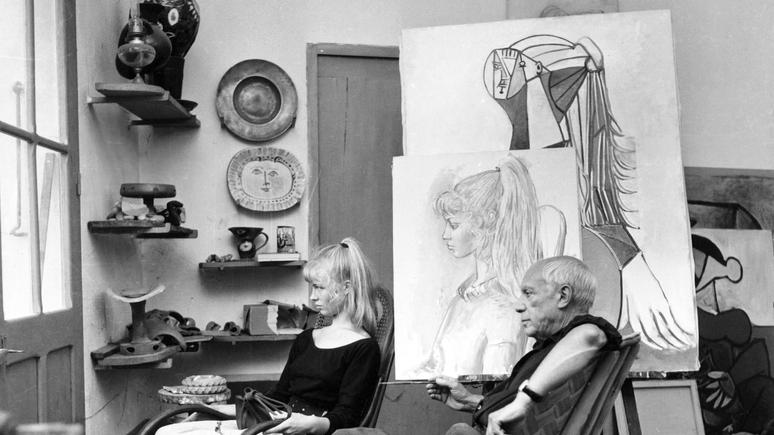

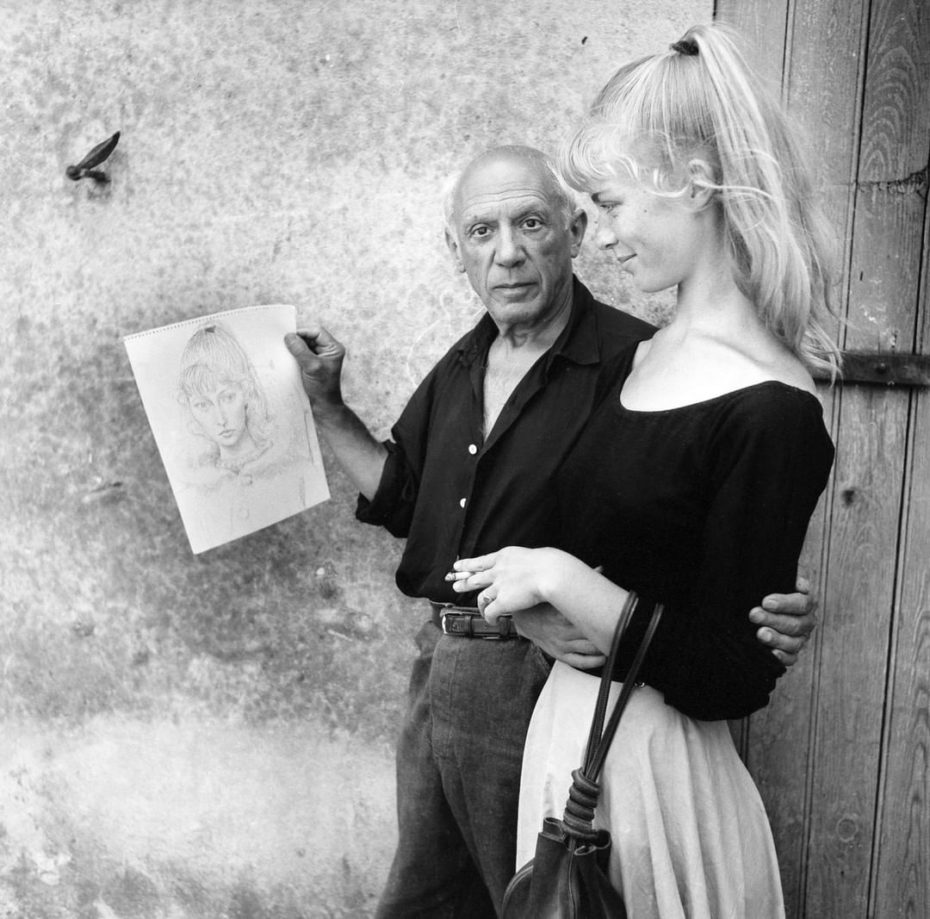

Later, he’d recall how Sylvette, this mystery girl with her charming high pony-tail, would walk past his studio every day and catch his eye. He began painting her from his memory, until she happened to see the artist holding up a sketch of what was a portrait of her face. “It was like an invitation,” she later said about the moment. She proceeded to waltz right into his studio, and Picasso, being Picasso, just said, “I want to paint you, paint Sylvette!”

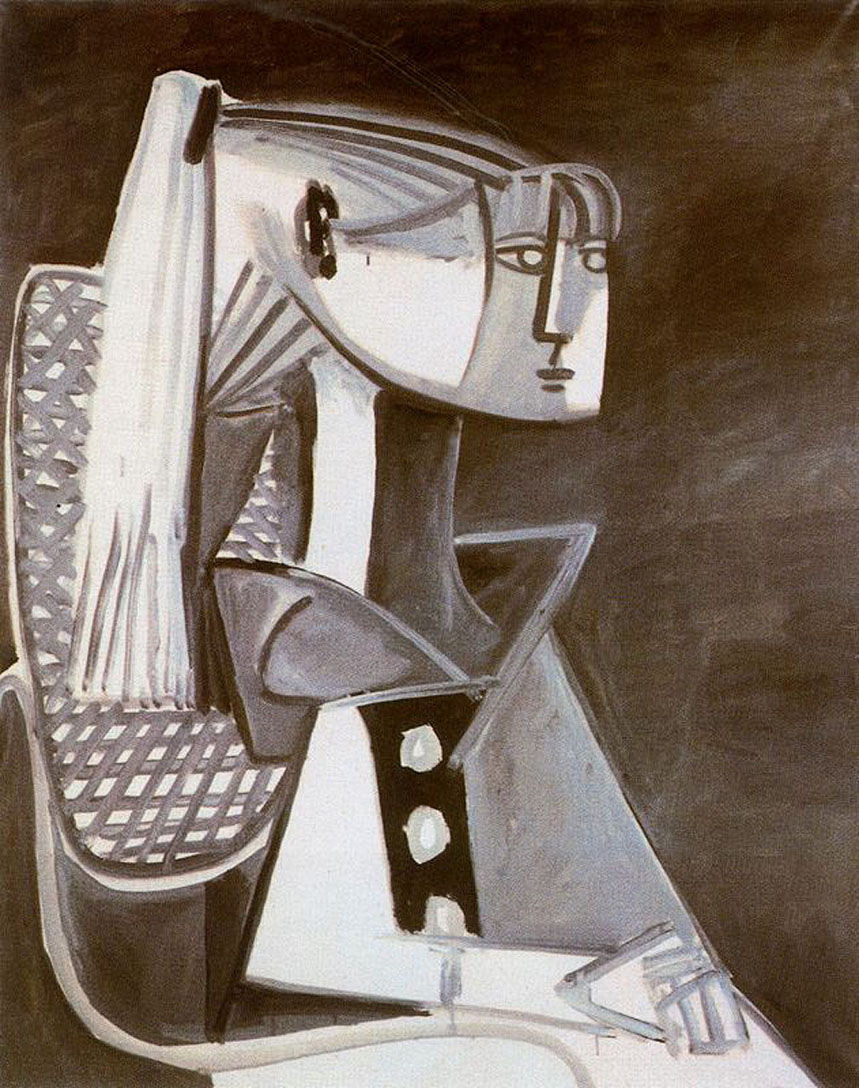

It was kismit. She would come over for hours on end, often posing in his rocking chair while he painted her, sketched her, sculpted her — you name the medium, he dabbled in it for Sylvette. That giant Picasso sculpture on Bleeker Street in New York City? That’s Sylvette. She was young but a whole lot of woman, with an energy that felt both relatable and ethereal. Also, that ponytail:

“I did it for my dad, whom I didn’t see very much because he was remarried,” revealed Sylvette. He had told her as a young girl, that he’d seen a Greek drama in Paris, and the girl in the play had a beautiful hairstyle, of a ponytail very high up, in the Greek manner. “That’s why I did it – for him.”

Picasso presented his collection of over 60 works in Paris to great acclaim, if not only because the art world wondered who this budding Mona Lisa really was. Even Brigitte Bardot, according to the muse, started sporting the look when she saw Sylvette donning it around Cannes.

In Brigitte’s biography, the screen siren wrote, “I went to see Picasso, but as he had already done Sylvette David, he didn’t want to do me.” (Finally, we discover why Picasso was the only man to resist Miss Bardot!)

“I thought that was very funny,” Sylvette later said in an interview for her own biography. “My life crossed their path – Bardot and Vadim – on the Croisette, in Cannes. We used to go there to look at the film festival, Toby and I. And we noticed each other, walking. She had brown hair, and she turned blonde after that. She became a beautiful blonde… I suppose she saw Paris Match, with me in it, and then went to see Picasso. She was more beautiful than me in a way: more sexy really. I wasn’t sexy; I was running away from sex! Funny, isn’t it? And Picasso could see that.”

Yet, as time went on, critics began pigeonholing the “Ponytail Period” nothing more than a footnote in Picasso’s career — an obsessional rebound from his split with former parnter, Françoise Gilot.

“The idea that this series lacks emotional engagement is a rather superficial psychological argument,” said Christoph Grunenberg, the director of Bremen’s Kunsthalle, to the BBC in 2014, “I don’t think you can reduce Picasso to a kind of flesh-eating vampire who feeds on other women and his subjects – it’s more complex than that.” For one, Sylvette was never even his lover. She didn’t even pose nude for the painter. Her fiancé, Toby, tried to keep a close eye on things as he did some work around the studio.

“Once, he took me into the barn where he kept his car”, recalled Sylvette to photographer Rosie Osborne in 2016. “It was an old Hispano Suiza, covered in dust. It was an amazing car. He opened the door and sat on the back seat. I hesitated, thinking, ‘shall I sit in there with him?, and then thought, ‘oh come on, don’t be silly.’ So I did. He sat there talking about all sorts of things and told me stories. He told me that creativity was happiness, and that any object can be interesting – that they all give you ideas. But he never touched me. He knew that if he had touched me, I would be off, like a deer!”

“Maybe it was her resistance to be seduced by him that made him need to see her,” he continued, “because he didn’t conquer her, he needed to conquer her on canvas and on paper and in sculpture…But even in the very sketchy portraits, where he tries to capture Sylvette in just a few lines and strokes, there is always great painterly expression. So one has to be very careful not to be judgemental.” Those in defence of the “Sylvettes” say they’re a testament to Picasso’s genius creative ability. “Suddenly, Picasso goes back to sheet metal,” adds Grunenberg about the range we get from the works, ” which he had used in his Cubist assemblage Guitar [1914]”:

Grunenberg’s observations are, in many ways, on the nose. But his vision of these muses as “conquests” is something Arne Glimcher of NY’s Pace Gallery would likely disagree with: “We’ve seen so much about Picasso as a misogynist,” he told The New York Times in 2014, “But someone who has so many women in his life doesn’t hate women. I think that’s ridiculous. Maybe he was not very good at maintaining relationships with women.” After all, he remained friends with Sylvette for the rest of his life. So what became of Sylvette?

Today, she’s a talented painter and ceramicist in her own right, living and working in a village in South Devon, England, under the name “Lydia Corbett” (she didn’t want to ride on Picasso’s coat tails). She told Country and Townhouse in a 2016 that the painter was like a father figure to her, and that the time they spent together influenced her own creativity more than she realised. “Picasso didn’t do small talk,” she said, “We would sit together in silence while he painted; this is where the artist goes – to an inner space, the visionary side of life. Through contemplation you go into another world…closer to your own soul…When you work spontaneously like this, beautiful things happen. ”

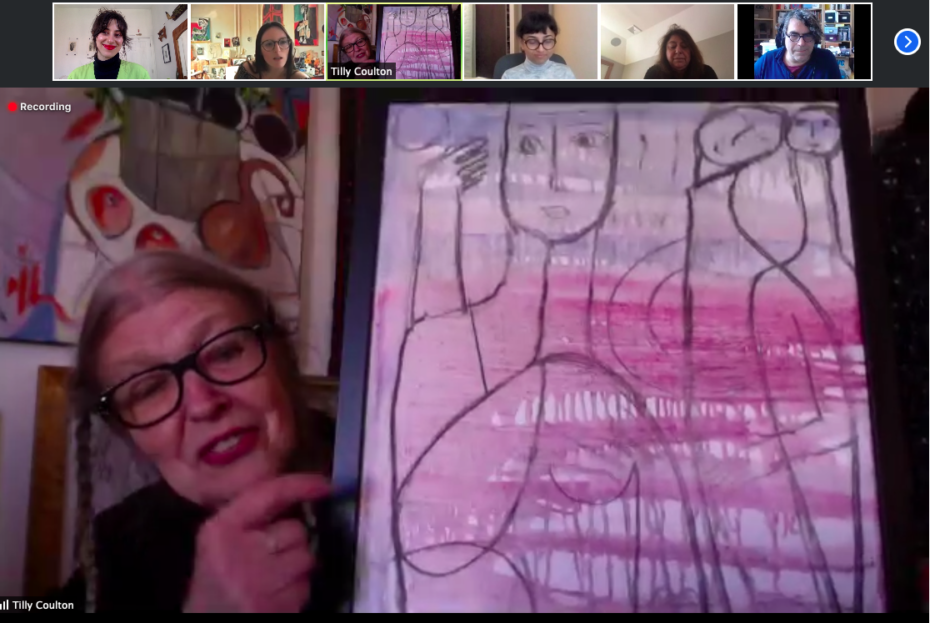

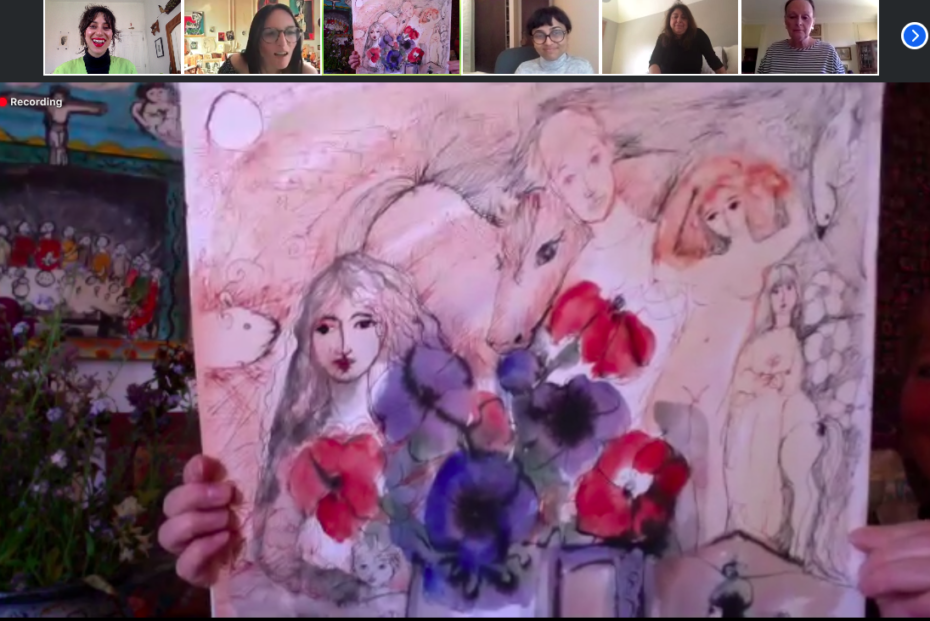

Check out her some of her wonderful art:

She has on online shop, where you can buy her beautiful oil paintings, watercolours, ceramics and prints. Her daughter Isabel is also a sculptor & woodworker, who’s art you can discover here. She also offers classes & workshops in Devon and artist residencies in the South of France.

There’s even a book, I was Sylvette, which is her engaging memoir about their time together. Discover more on her website.

We held a Zoom Q&A with Sylvette during the Covid-19 Lockdowns. You can re-watch all the wonderful moments in the full Video Event here in the Keyholder Vault:

We’ve also transcribed a few of the questions for everyone to whet your appetite…

Messy Nessy Chic: Hello, Sylvette! Or shall we call you Lydia? You sign your paintings both “Sylvette David” and “Lydia Corbett,” right?

Lydia Corbett: That’s right. The past, future, and present. I changed my name in the 1960s.

MNC: Your daughter, Isabel Coulton – who is also a talented sculptor – is also joining us just beside you – hello! [Isabel waves]

So, Lydia, the word “muse” has been with you for most of your life. How do you feel about that?

LC: To me it was a miracle, really. I felt I was nothing. I was afraid of everything. I’m very confident now, but I was shy when I was 19-years-old. I didn’t say a word. Picasso actually painted me with no mouth one day.

MNC: How did you first meet?

LC: When I was sitting on a poterie– there were terraces in Vallauris, France, where I lived with my boyfriend Toby [Jellinek] – and we would sit there drinking coffee. Picasso had a studio just above the hill. He could see us sitting there, and I think he was looking and wondering, because he came with a painting of a girl with a ponytail over the wall.

We all saw it and thought – Oh! That’s an invitation. So we opened the gate, rushed in, and it was like a miracle really. He was already very famous [he was 73, Sylvette was 19]. Also, we came in with another lovely young girl – more sexy than I – and he still said, “Oh, no. I want to paint Slyvette!” while I just thought I am lacking! [laughs].

MNC: What was a typical day like at his atelier in Vallauris, France?

LC: I just sat in his studio in a rocking chair, very quiet while he painted. Picasso left his body outside the studio door, and walked in with his spirit. I think that’s magical. We were both in a state of contemplation, maybe. I was very quiet. But he noticed I like smoking [cigarettes] which I learned in a school in England [laughs] so he would buy me a packet and put it on the table near my chair, and I could smoke as much as I liked. And he did too [smiles]. He smoked Gauloises, which come in a big blue box with a lady in Spanish dress. He would make a pyramid on the floor and say, “Look! We’ve smoked all this” [laughs]. It could have been an art installation.

MNC Audience member: What was Picasso’s temperament like when you were around him?

LC: Oh, he liked playing games. He wanted me to laugh I think. He’d put on funny glasses with a moustache and a Gary Cooper hat. All sorts of tricks. He would draw a spider on the floor, for instance, and then forget about it and jump so high! One day I had the hiccups, so he jumped up with a knife as a joke and I thought Oh my he’s gone mad! [laughs]. But, it stopped my hiccups. One day we visited the old poterie, and upstairs there was this little bedroom, a lot like Van Gogh’s “Bedroom in Arles,” and he began jumping up and down on the bed!

MNC: And of course, Picasso has the reputation of being with many women.

LC: Oh, yes – but he didn’t flirt or touch me at all. There was another day we were sitting in his car, a big old Hispano-Suiza in a barn full of cobwebs. He opened the door, sat in the corner and said, “Come in, we’re going for a ride without a chauffeur!”I hesitated to go in – but I thought, Ok, come on, Sylvette! Don’t be silly. So I sat with him, and he was very, very noble. We went for a ride in our imagination, I suppose, down memory lane.

I had a hard time hearing what he said because he had a very strong Spanish accent. And I wouldn’t dare say, “Oh what did you say? I didn’t get that.” I was sitting quietly, listening. He talked about this poetry. About his friend who died. He was living between the past, the present, and the future. We all do that. He told me stories of his life in Spain with the circus people and animals. He loved animals. Birds. The dove. I’ve been very inspired by Picasso, and I always put the dove in my pictures. It’s the spirit of hope.

MNC: What advice would you give today to your 19-yr-old self, about to meet Picasso?

LC: I would’ve asked more questions. But I wouldn’t be different. I’m still innocent in the mind, and young in spirit. Maybe we would have been lovers. Who knows. I might have fallen in love because he was very handsome, even at 73-years-old. But I saw him more like a father figure.

It’s funny, I feel I am closer now to Picasso than when I was young.

MNC Audience member: What did beauty mean to you when you were young, and how has it evolved?

LC: Well…I don’t know. When I was young I didn’t think very much about beauty. I didn’t like myself at all!

I was simple minded and shy. I didn’t talk. People used to have dances outside in Vallauris at the square, for example, and I loved to dance but Toby didn’t, so I couldn’t. At that time you couldn’t dance on your own like you can now. I think I was very closed-in.

MNC: We’re quite hard on ourselves when we’re young.

LC: Yes, you don’t know what you see. Picasso saw something special. He showed me how to love my body by drawing it.

One day I came in to the studio and Picasso had done a portrait of me with my breast out and said, “I hope you don’t mind,” and I thought Well, I bet he wants me to pose in the nude… but I was much too shy. It’s a shame I didn’t! Now I would have lovely nudes. Children are so frightened and full of complexes.

MNC: You partially grew up on a small naturist island off the Côte d’Azur?

LC: Yes with my little brother. We used to swim, and eat fish and run through the bushes with bare feet. But I wasn’t that happy. I don’t know why… I had lots of problems in my youth. I felt separate from other people. I’ve always felt separate. Some people are like that. Maybe Picasso saw that, you know? He was quite an open man. He could see my fears. He could see I had been hurt.

MNC Audience member: Why did you start wearing your hair in that iconic ponytail?

LC: My father went to that beautiful Greek tragedy, Antigone, and he told me the actress had this ponytail – amazingly high. Sometimes it would fall around me like a cape. It was beautiful.

MNC: There’s also that wonderful photo of you coming out of the beaded doorway wearing that – what was it, the fabric of that skirt?

LC: Oh yes! The little squares. My mother made it. Cotton gingham, black and white. I never liked to show my legs. Always long skirts, long sleeves.

MNC Audience member: It’s been suggested that Brigitte Bardot’s whole look was also inspired by you. Can you speak about that?

LC: Toby and I were walking down the Croisette des anglais in Cannes one evening, and there we crossed Brigitte and [Roger] Vadim, her first husband. She had dark hair then. After that she turned blonde and did my hairstyle. She looked beautiful! Very sophisticated, of course. Not simple like I was. I was a natural type, while she was in this [stylised] film industry.

MNC: At that point, Picasso’s “Ponytail Series” of you – over 60 works – was a sensation. You were in Paris Match magazine. How did you feel about that fame?

LC: I was in a railway station one day waiting for someone when this tall man came and said, “Here’s my card.” Nothing else. I looked at it, and it said “Jacques Tati.”

MNC: A legendary filmmaker.

LC: I love Jacques Tati. But I told myself, no never the film industry. I was frightened of the industry and of men and the stories you heard at the time for girls. Hollywood was also interested, but I wanted to be a painter. That’s what I had always liked.

MNC: You really began professionally painting in your forties, and now you’ve even been exhibited at the Tate! How did you come into yourself as an artist?

LC: Well my father had a gallery in Paris. I didn’t see him very often but he inspired me a lot. My mother was a very good impressionist painter. Little by little I thought, I’m becoming better. [A prominent] gallery in London finally said, “We’ll try you in a show with nine artists. If you sell all your work we’ll take you on.” I sold them all. Shall we share some paintings?

MNC: Please!

MNC: What’ve been your other artistic influences?

LC: All the Italian painters. Giotto. Piero della Francesca. The Flemish, with their beautiful Madonnas. Rembrandt. My mother and father.

MNC: Are you fully self-taught?

LC: Yes. I learned nothing at school [laughs]. I thought it was dreadful.

MNC: What do you think Picasso would say about your art?

LC: I wonder [laughs]. I think he would like my current work better. It’s less fiddly, with better storytelling. Here’s another new one called “Tenderness.”

MNC Audience member: Did he ever pay you for your work as his model & muse?

LC: He offered, but I said no. We were very poor actually. So Picasso paid my boyfriend Toby to do a cutout of that sculpture in New York City. That was very thoughtful, I thought.

MNC Audience member: What do you think you learned from each other?

LC: I would be honored if he learned something from me, because I was like a blank chalkboard. He drew on my heart. I can’t forget Picasso. My work is full of him. He did thank me one day; he said, “I was very grateful you were here with me at that time,” because he’d lost his [first wife] Françoise Gilot, and the children [when they split]. And he gave me two artworks. I was very spoilt really.

I always liked older people when I was young, because they had wisdom. I love to know the truth. I’ve always been looking for god, really. Now I look back, and I know that just sitting like that with Picasso, in contemplation, was a kind of meditation.

MNC: Would it be fair to say Picasso became your muse?

LC: A muse with a muse, that’s true! I paint him and Toby often.

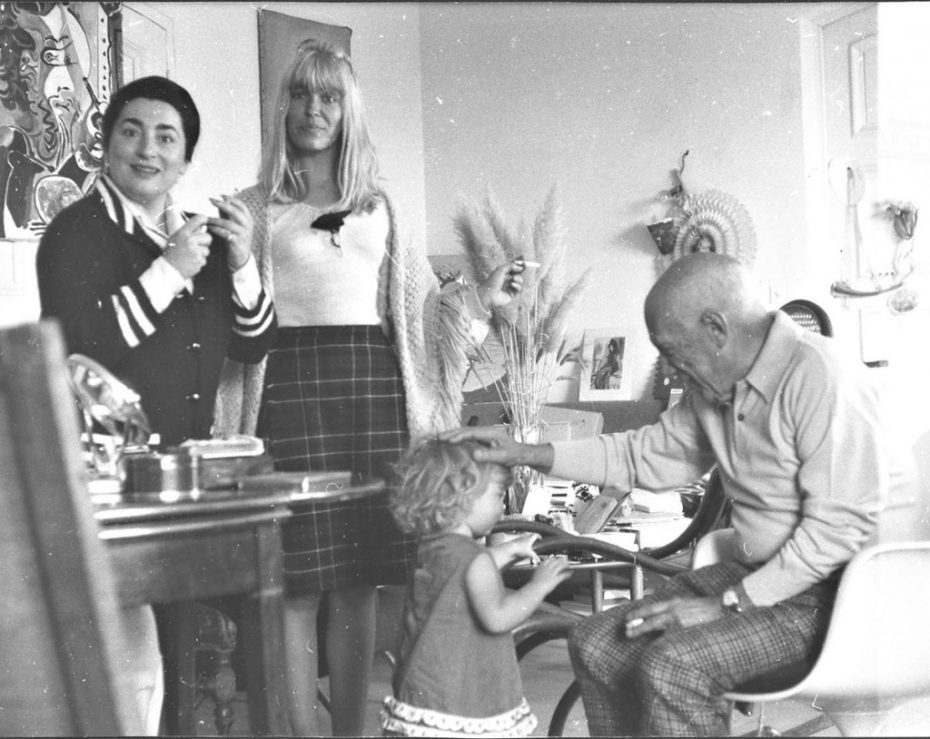

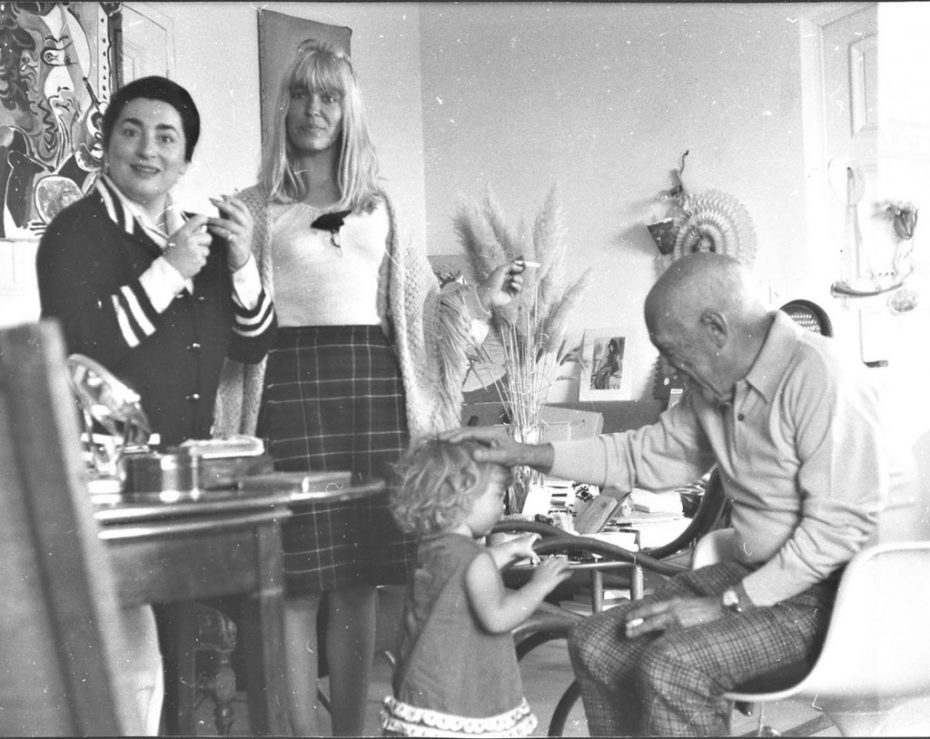

MNC: Do you remember the last time you saw Picasso?

LC: Yes I saw him with Isabel in 1963 – or ’65? He had moved houses. It was hard to see him, but we made a lot of noise at the gate and finally the gardener opened the door. Jacqueline [Roque] was there. She was very kind, smoking cigarettes – and I was too [laughs]. Isabel was making Picasso go round and round in a chair! She was so funny with her little curly hair. He said, “Oh she really looks like a proper English girl, like a Gainsborough painting.”

MNC: Where do you find happiness?

LC: For me, the happiest moment is sitting still in the present. Paint a bit. Go for a walk, and meet nobody. We are very lucky, human beings. We have different levels of understanding. Dimensions. I sing a song of amazement.

MNC: Lydia, thank you very much for speaking with us. This is a call we’ll never forget.

LC: Thank you, all of you. And I wish you all happiness in finding yourselves – your true selves.