Phoebe Roberts.

It’s Edwardian Era Glasgow, circa 1914, and the stress mounting in St. Andrews’s Hall is unbearable. Flocks of Suffragettes and policemen are waiting for the woman of the hour, Emmeline Pankhurst, to magically surface and fight against her own arrest — the tension is so palpable, you could cut it with a knife. Or karate-chop it, which is exactly what “the Bodyguard”, a top-secret secret society of feminists, decided to do. They were corseted, they were clever, and they could flip a man over like a pancake.

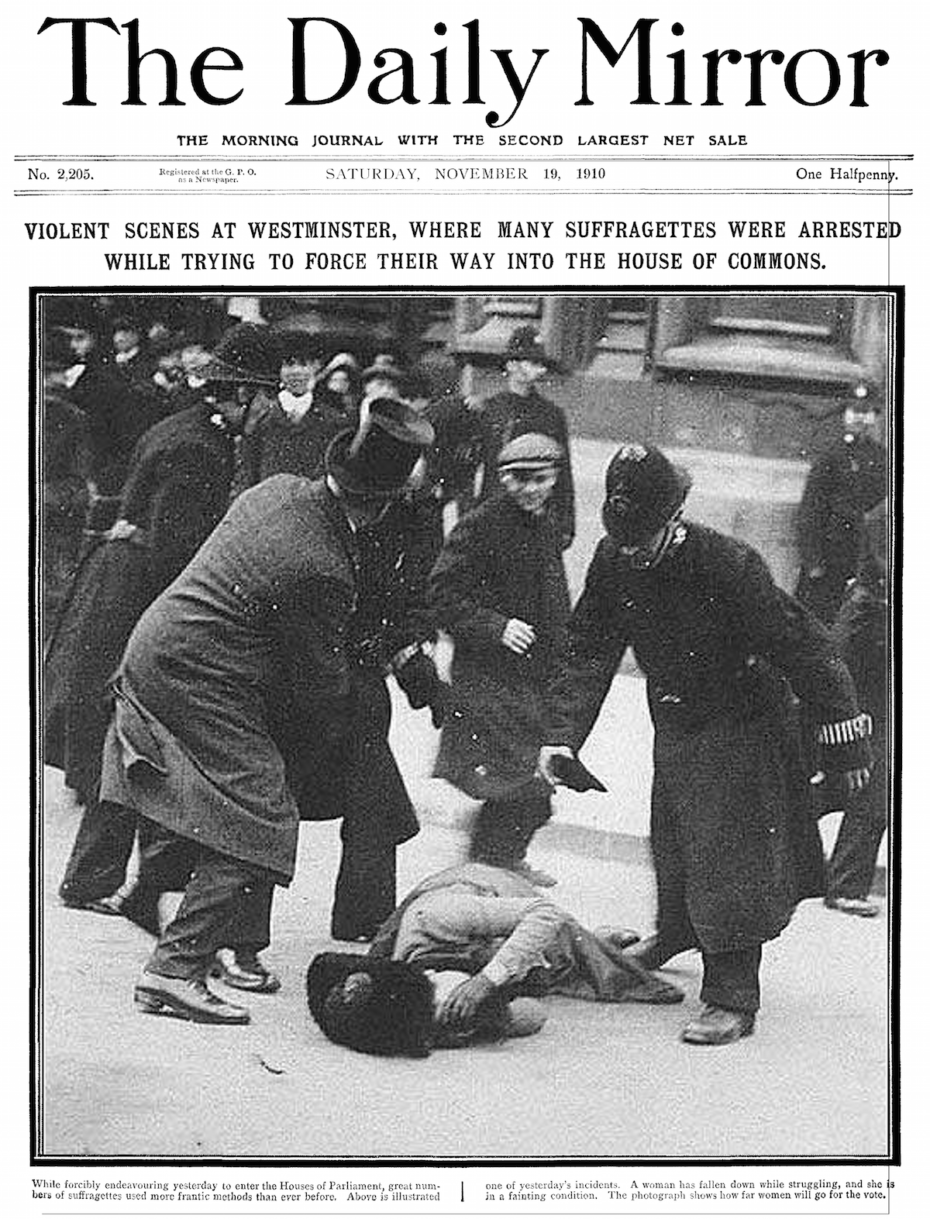

It sounds like some kind of amazing feminist genre fiction, but it’s true. “The struggle became increasingly bitter between women and the police,” explained BBC journalists Camila Ruz and Justin Parkinson in 2015, in an article about the discord between women and the government in the fight for justice. Suffragettes, you see, were being jailed and thrown into a cycle of what the police called “Cat and Mouse”, wrote Ruz and Parkinson, “[They] were arrested and, when they went on hunger strike, were force-fed using rubber tubes.” When they reached a reasonable weight again, officers released them with the intention of tossing them back behind bars.

One of the boiling points that led to the assembly of the Bodyguard was “Black Friday,” the infamous 1910 rally that saw 300 women march on Parliament. So many were battered and sexually assaulted — two even died — that it became clear they had to learn to defend themselves. “Women started putting cardboard over their ribs for protection,” write Ruz and Parkinson, and it was women like Sylvia Pankhurst (below) and her mother, Emmeline, who began seeking out martial arts training:

Sylvia Pankhurst

Garrud’s school for young women.

“We have not yet made ourselves a match for the police, and we have got to do it,” explained Sylvia in a speech, “I advise you to learn jiu-jitsu…Don’t come to meetings without sticks in future, men and women alike. It is worth while really striking. It is no use pretending. We have got to fight.”

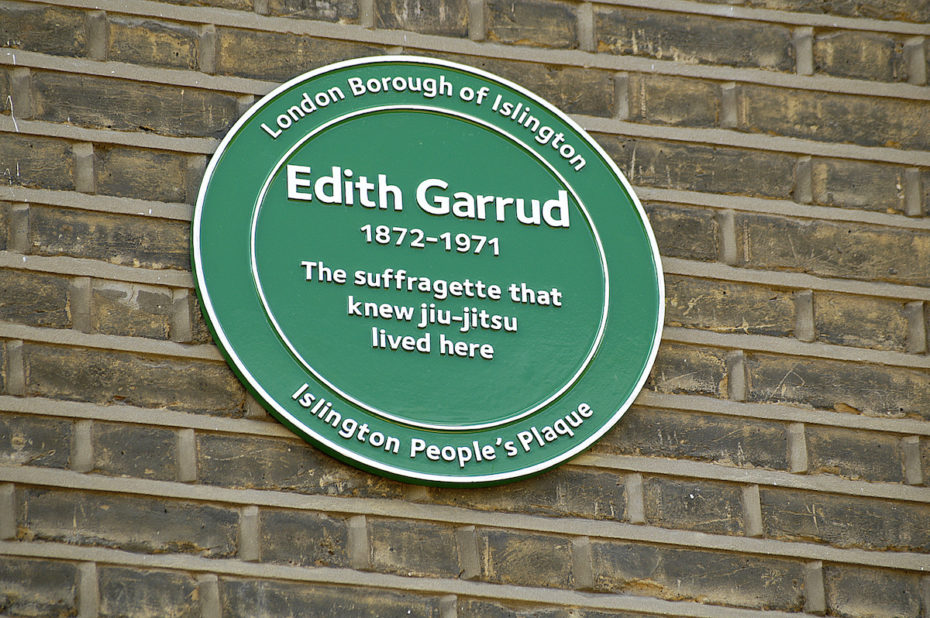

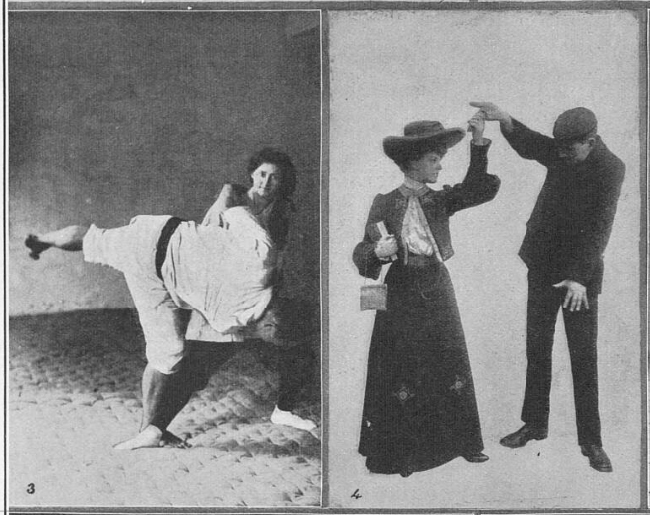

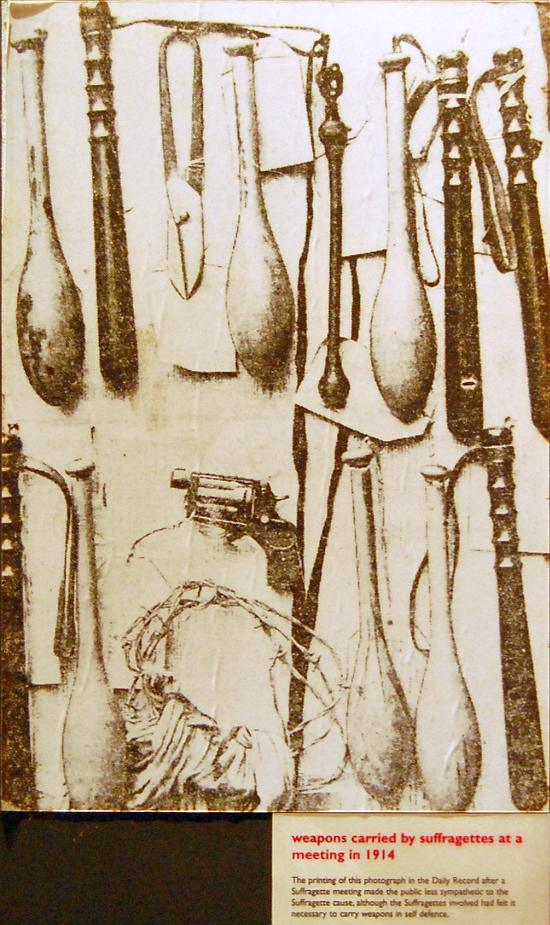

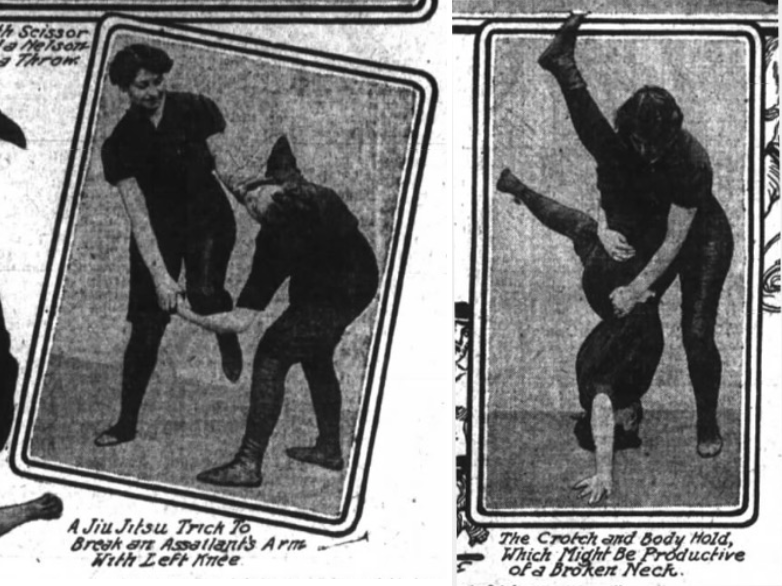

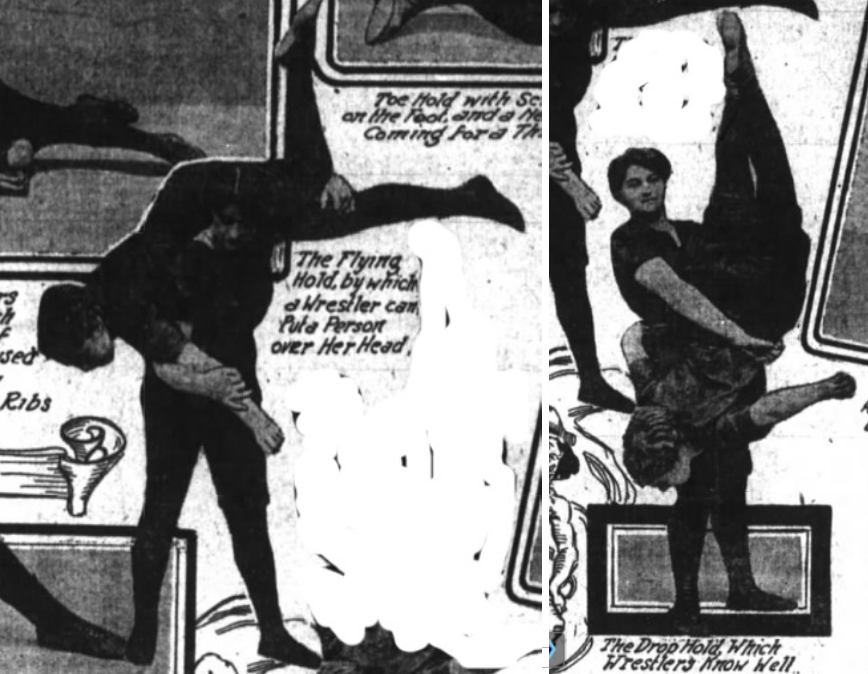

Enter Edith Garrud, the jiu-jitsu master who taught the women, “the thinker’s mode of self defence,” explains historian Dr. Emelyne Godfrey. Garrud was one of the first female Western instructor of the martial art form in the West, and at Pankhurst’s urging made it the a hidden back bone of the women’s movement. Prior, they’d only had small bats and crude weapons to hide in their bonnets and garters. Knowing jiu-jitsu, however, meant possessing an invisible (and much safer) tool.

In a way, it’s the underdog’s martial arts form, because Jiu-jitsu relies on understanding how to use an opponent’s weight to one’s own advantage. “Jiu-jistu literally means ‘the soft art’,” explained Garrud, who was herself only 4ft. 11 inches, “it’s the balance of art an leverage, as easy as A, B, C, and as easily learnt as a child learns to walk.”

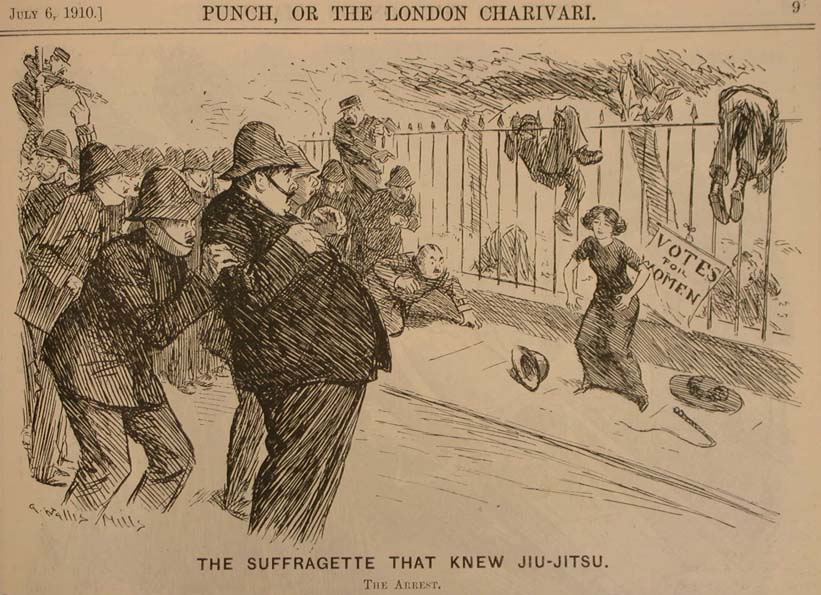

Needless to say, the press couldn’t get enough of it. They called the women, “Amazons,” and ran caricatural articles on their happenings. They paid no mind, and eventually a small battalion of 25-30 women — those willing to risk it all — volunteered to be the collective “Bodyguard” of the movement’s most important figures, like Pankhurst. And thank goodness, because on March 9th of 1914, they had to come out in full force to save her.

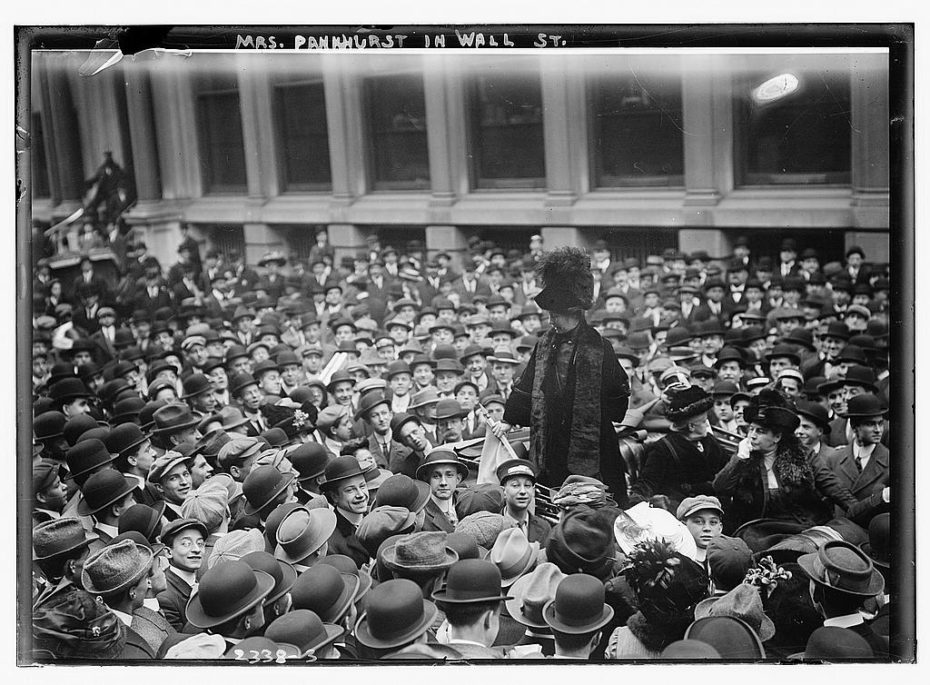

Today, the violent episode is known as “The Battle of Glasgow”, but you likely won’t learn about it in history class. It was during a Suffragette rally in Scotland, and police were waiting impatiently to arrest Pankhurst, who snuck in under-cover as a mere attendee. Her martial arts training, you see, had taught her just as much about the art of confrontation as it had enemy manipulation, and by the time Pankhurst took to the stage (with a throng of disguised “Bodyguards” behind her), police were dumbfounded.

Suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst.

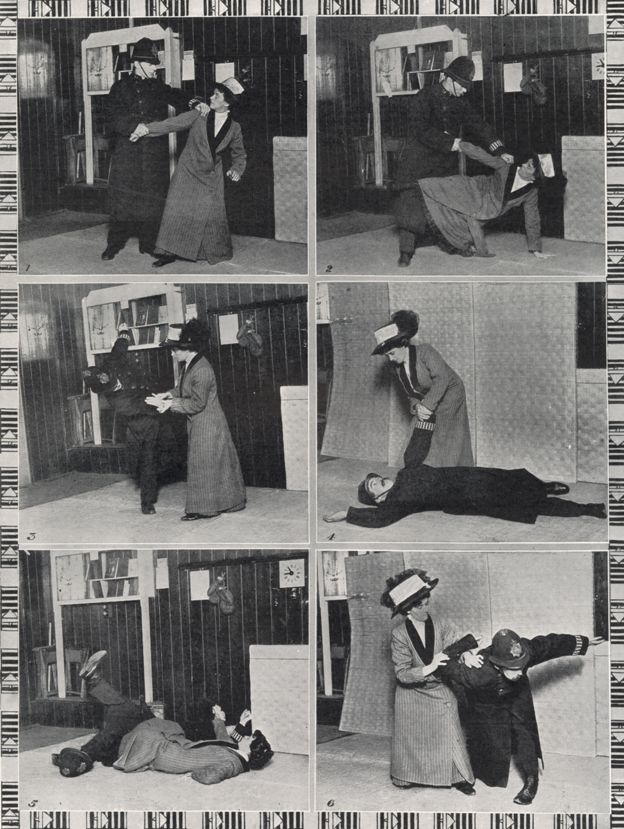

They eventually arrested her that day, but not without an impressive fight on the women’s end; when officers threatened them with bats, the Bodyguards whipped out floral bouquets filled with barbed wire; when men tried to grope them on the way out, they could disarm them with a mere twist of the pinky finger. They hadn’t won the fight yet, but their message was made clear: women united are a force to be reckoned with. It wouldn’t be until 2011 that Garrud finally received a posthumous plaque to commemorate her contribution to Women’s Rights:

We’ll leave you with a little tutorial on how to open up a can of whoop ass à la 1926: