Meet the latest maverick of the architecture world to steal our hearts, Bruce Goff. Lesser known amongst design laity, but just as groundbreaking as his fellow Midwesterner and mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright, Goff’s work was quite simply jaw-dropping. Case in point? The domed, technicolour house above. It might look like a groovy LA pad from the 1970s, but this baby was built in the Middle of Nowhere, Illinois (drumroll) in 1948…

“He was a child prodigy who built his first house at age 14,” says the LA Conservatory about the only pupil Frank Lloyd Wright ever openly praised. “A musician who translated notes into buildings”, Bruce Goff was an architect with no formal academic training, and yet, he’s responsible for some of the most iconoclastic architectural designs of the American West.

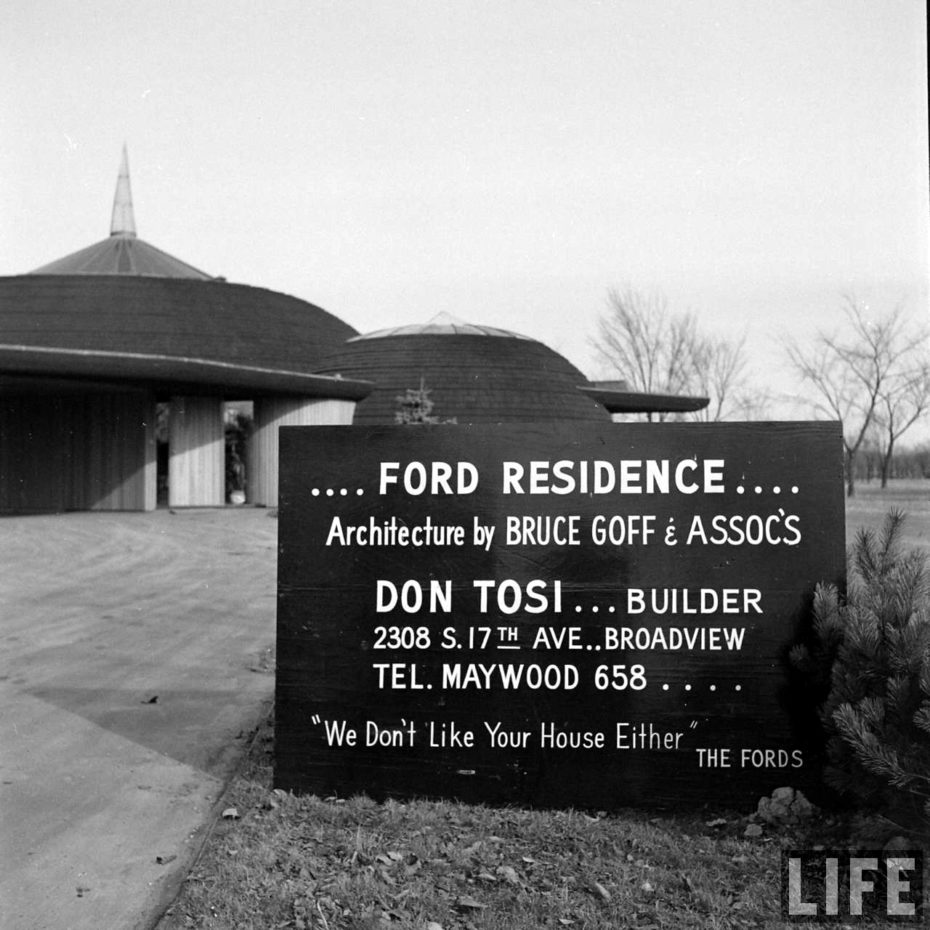

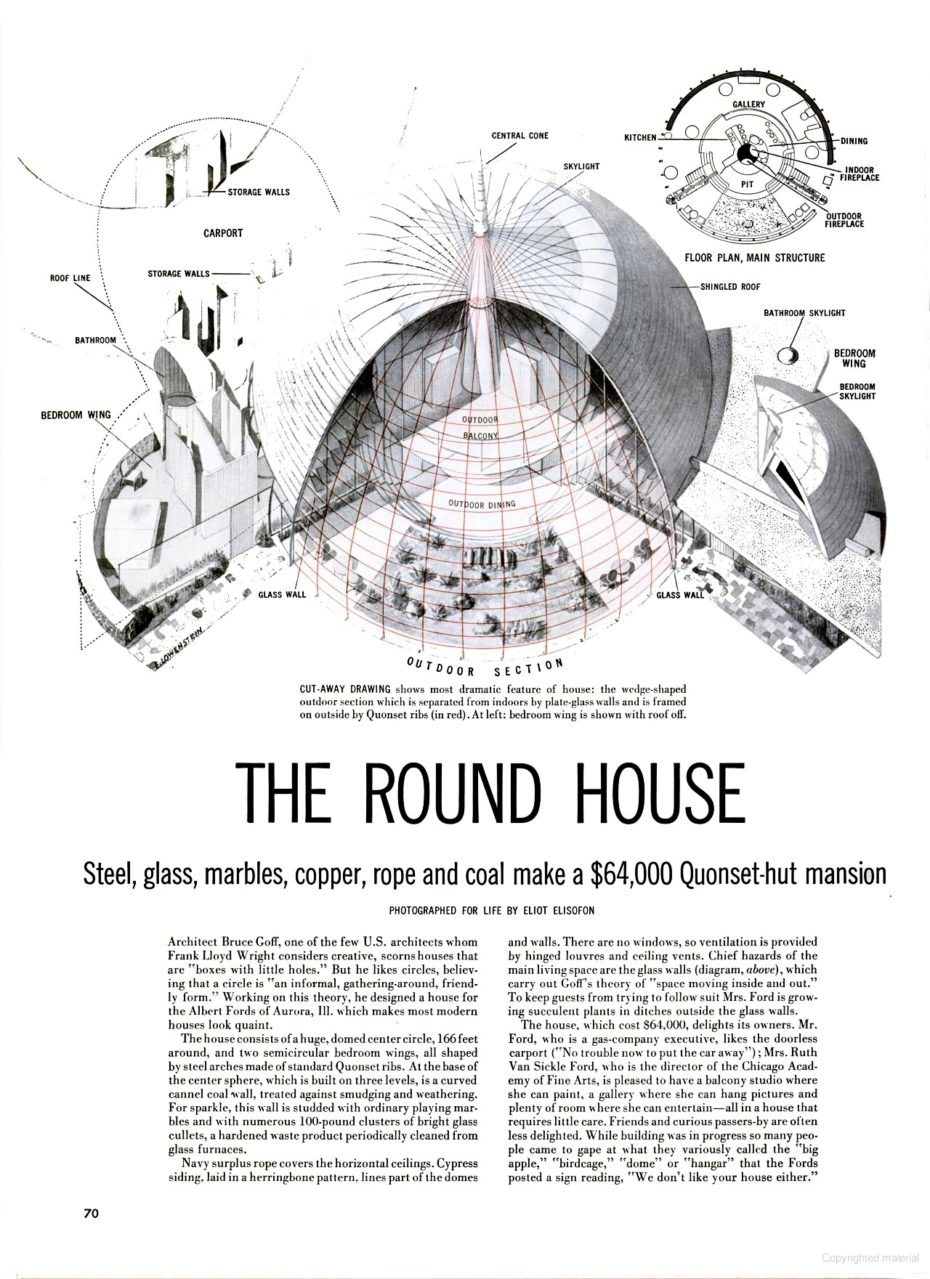

The Aurora house was easily mocked by conservative tastes in Illinois. Critics called it “The round house made of cannel coal”, poking fun at Goff’s unorthodox use of materials like coal and exposed steel ribs. Luckily the couple who commissioned it, Mr. and Mrs. A.G. Ford, had a staunch sense of humour…

“There’s a sign outside the new home [they] are building here,” wrote Evening Citizen in 1950, “It reads, ‘we don’t like your house either’. That retort is designed to ward off wise-cracks, because the Fords’ new house invites them. The structure looks like a big apple buried in the ground with two tangerines alongside.”

Goff was born in rural Kansas, and spent most of his life living and working in Oklahoma. “His father spotted his incredible drawing talent early on,” says the Conservatory, and helped his son to “secure an apprenticeship with the architecture firm of Rush, Endacott & Rush at the age of 12.”

He became chair of the architecture department at the University of Oklahoma and designed hundreds of structures, yet his legacy has not just fallen, but crumbled to the wayside. Why? Undoubtedly, because the cooler-than-thou designers of the coast turned up their noses at his brand Midwestern kitsch, which dared to say that what feels zen, and, frankly, insane, could both occupy the same space. His buildings, whose materials were often unorthodox and sometimes impractical, were much more an exercise in philosophy than practicality.

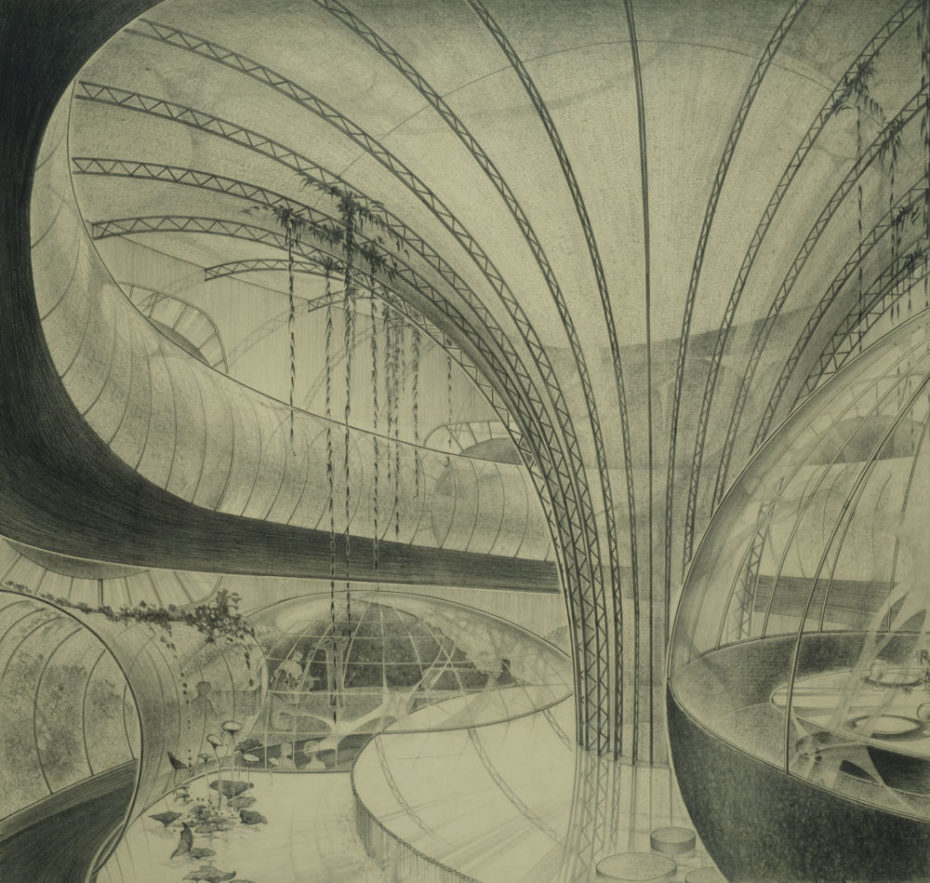

He died in 1983, survived by structures that had a knack for feeling both futuristic and folkloric, a fleet of Native American spaceships if you will, by using waste glass, feathers, redwood shingles and Quonset ribs. Just check out Shinenkan, which burnt down in the 1990s, but was the most surreal bachelor pad:

“It had clear plastic strips, known as cellophane rain, streaming from a skylight,” a pair of newlywed architects told the NY Times in 2003 who’d stayed at the house the year before it was destroyed by arson. They were die-hard Goff fans, a rarity in the design community in the ’90s, and still have fond memories of the night they spent inside its crystalline walls. “[There were] dime-store glass ashtrays affixed to the windows for a kaleidoscope effect,” they said, “and walls made from pieces of coal. The whole place was a big bed, more or less.”

Studio Interior, photo by Nelson Brackin.

Despite being praised in the media by his birthday twin bud Frank Lloyd Wright (both June 8th Geminis), Goff was just too weird for the design community. The relationship between Wright and Goff was a curious one, with the former becoming both an admirer, friend, and mentor to the architect. What started out as a flurry pen-pal exchanges became a lifelong creative relationship, with Wright as Goff’s sole cheerleader in the design industry, always pushing him to go the extra mile and, actually, to completely avoid formal architecture study. In another lifetime, we like to think they’d of been partners of a killer, super weird agency…

Goff (left) with Frank Lloyd Wright.

“His midcentury houses across the Midwest are symbols of both a heartland-born eccentricity and a distinct Modernism,” wrote Times journalist Amanda Fortini in an effort to uplift his work, “So why has he been forgotten?”

In a 66-year career, he designed over 500 projects for folks of all walks of life…

The Glenn Harder House in Mountain Lake, MN. ©Anthony Thompson

Oh that? Just a Japanese-style hobbit house in the middle of a corn field.

“In our era of restrained minimalism, when architecture is almost always the province of the rich, it may be that Goff, with his aesthetic idiosyncrasies and affinity for middle-class Midwestern clients (schoolteachers, farmers, salesmen, small-town newspaper publishers), still has lessons to teach us. His daring, elaborately imagined homes are often dismissed as corny, but they possess a warmth, an earthiness and a wild ingenuity that serve as an antidote to the soberly luxurious.”

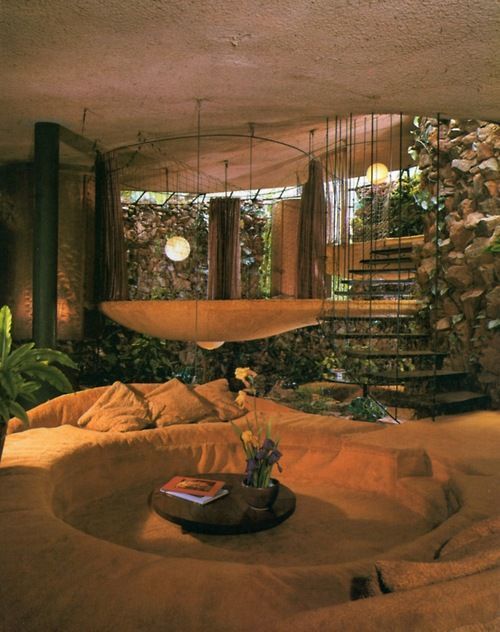

We couldn’t agree more, and it’s a tragedy many of his masterpieces have been destroyed. One of the greatest losses was the 1955 “Bavinger” house, which looked like a kind of eccentric pirate ship plopped down in rural Oklahoma…

Bavinger House. Wikimedia Commons.

According to ArchPaper, no one was living in the home that Goff considered the ultimate ode to creating organic, regenerative living. “This house begins again and again,” Goff said, “Gertrude Stein talks about the sense of not being in the past, present or future tense, but in the ‘continuous present.’ I was thinking in those terms.” The walls were made from hundreds of tons of local “ironrock” that Goff has dynamited from a local field, and he upcycled an oil field drill stem to uphold the building, whose only walls were curtains and glass at the many, mounting platforms of its coiling blueprint.

Interiors were auctioned off of the crumbling house in 2015, and it was razed to the ground.

Tracking down which structures are still standing and open to visitors can be a bit of a saga with Goff, so we’d suggest visiting his last masterpiece, a serene pavilion for Japanese artworks, at LACMA. Plan your pilgrimage here. In the meantime, we’ll leave you with some more of his greatest hits…

Frank House, Sapulpa, Oklahoma, 1955 © Jeff M. Jones

Durst House 1958 © Ben Hill

Triangle grille panels, Bartsville Oklahoma, photo by David Alan Milstead.

The Riverside Studio was built in Tulsa in 1928, originally built as home

The Strukus House, Bruce Goff’s last masterpiece built in 1982 in Woodland Hills © Michael Locke

Octagonal Nicol House 1964 © Roy Inman