Paris: The Birthplace of Communism explained

Belleville is a neighbourhood in the East of Paris that has a vibrant multicultural community. It’s French, it’s Chinese, it’s Vietnamese, it’s Moroccan, Tunisian, it’s Jewish, it’s Muslim, it’s Christian, it’s even part hipster too. And they all co-exist here peacefully. On the main boulevard, you’ll find a hodgepodge of Asian restaurants and markets that alternate with Arabic pastry shops, Tunisian-Jewish coffee shops and bohemian dive bars. And you can’t leave Belleville without trying a world-class bowl of Vietnamese Pho soup. But as we head up the hill, you start to notice something a little more peculiar about Belleville. There’s an air of rebellion in the neighbourhood that gave birth to Edith Piaf, who according to legend, was born under a streetlight on the corner of Rue de Belleville. And do you want to know what else was born here? It’s no legend, it’s more like the elephant in the room. Communism was born here– not in revolutionary Russia or in Maoist China. Communism was born right here in this quaint little Parisian village.

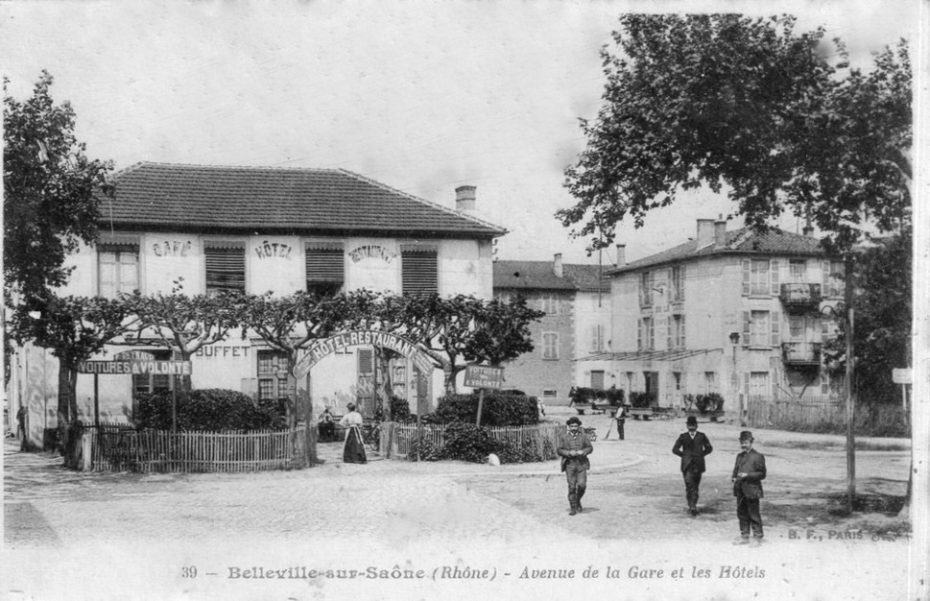

Belleville started out as a provincial wine-making village on a hill, made up of working-class folks and until 1860, it wasn’t actually part of Paris as we know it– and you can probably find a few residents who still don’t believe it is. Until quite recently, if you were to spend time in this neighbourhood, you could detect a different Parisian accent, even a different dialect of French, spoken only by the residents of Belleville. Along with several other villages around Paris like Montmartre in the north, you could say Belleville was like its own isolated mini state of Parisians that pretty much did most of the hard labour for the bourgeoisie. As such, it became quite the hotbed for the worker’s struggle.

Okay, hang on, it’s time to fill you in on some forgotten history.

Aftermath of the Prussian Siege of Paris

We’re all familiar with the French Revolution right? Remember Marie Antoinette? Well almost 100 years after that, France had just lost a really stupid war against the Prussian empire (what is now Germany), and France was about to literally hand over the city of Paris to the Prussian army. This new puppet government wanted to see the old French monarchy restored (and go back to its old ways of “Let them eat cake!”). So for the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy, the surrender was actually a pretty good deal– it was going to leave the Prussians to deal with the rising unrest of the working class in Paris, who by any standards seemed like the only true patriots left in the country. But the working class didn’t like the idea of giving up their city to the Germans, and they certainly didn’t want anymore “sun kings” and power-crazed monarchs.

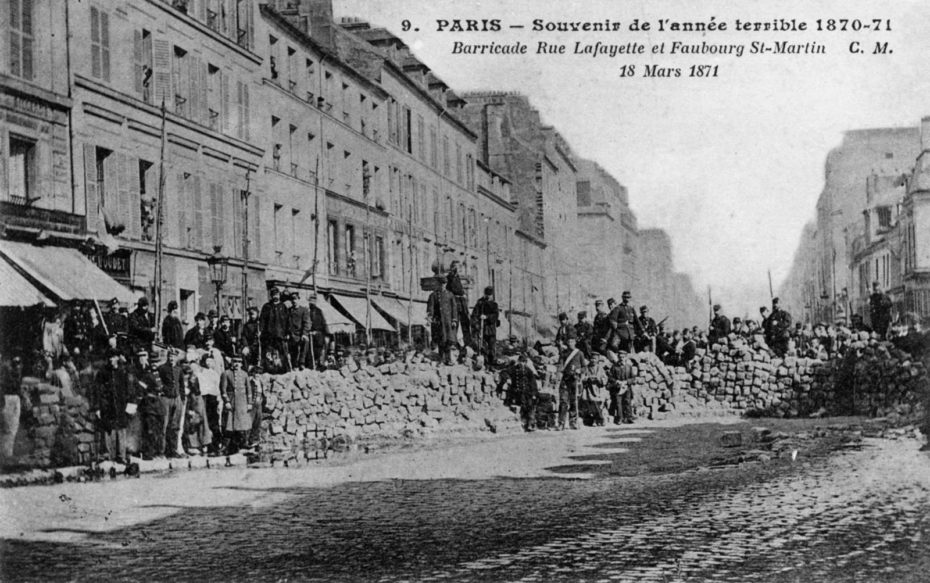

So they decided to take over the city themselves and start a pretty major revolution. Except this one kind of got shoved under the carpet of French history. You might not have heard much about the Paris Commune of 1871, because it’s an event that would still scare the crap out of any modern western government.

In a nutshell, for 72 days in 1871, ordinary working class folks actually managed to seize control of Paris and set up their own government in the capital. Never before in history had any government ever claimed to represent the interests of the working class. It was a major deal.

For the brief amount of time that they were in power, it almost seemed like they had things in order and that they were actually getting at something. These weren’t just disgruntled hooligans looking to stir up trouble– this was a real movement of forward-thinking people and middle class intellectuals from all across Paris, who came together to fight for justice. And they wanted pretty basic things, like better living conditions, better wages and for Paris to have its own mayor.

In the short time they had, the Commune’s government even managed to abolish night-time baking– so that the working class wouldn’t have to be up all night baking croissants for the rich.

Women were a huge part of the Commune too, way ahead of their time, fighting for things like free education and the right to divorce. Women especially, fought to the very end during the Paris Commune. They not only chaired committees, but also built barricades and participated in armed battle.

Louise Michel, a French teacher, writer and poet who was an active member of the Paris Commune and earned the nickname “Red Maiden of Montmartre,” later wrote in her memoirs, “oh, I’m a savage all right, I like the smell of gunpowder, grapeshot flying through the air, but above all, I’m devoted to the Revolution.” She was exiled to New Caledonia in 1873.

The radical Parisians were made out to be godless socialists who were drinking the wine of the rich. Troops from Versailles were sent in to slaughter anyone that looked like they might be a radical. If you had rough hands from hard labour or spoke French with a funny accent, you were shot on site. People were killing each other in the streets, left right and centre. It was chaos. Paris was a complete war zone.

It’s thought somewhere in the neighbourhood of 15000 Parisians were killed in one week, and it went down in history known as “the Bloody Week”. And Belleville was at the centre of it all– the last frontier. Almost half of the neighbourhood’s population was wiped out in a bloody final battle against the French government. They held out to the very end.

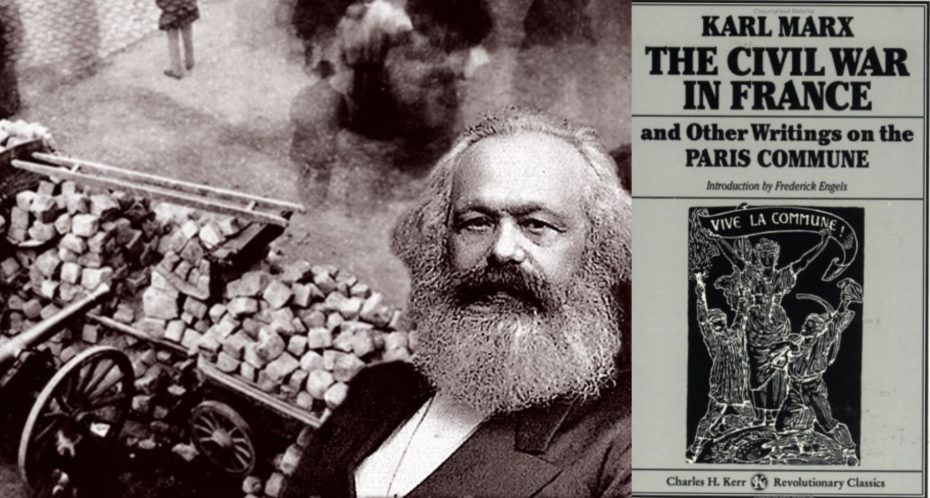

While the Paris Commune didn’t have much time, it could be considered as the first real attempt to work out a communist society in practice. And for a certain someone, it served as the blueprint of communism. Enter Karl Marx, you know, the guy who wrote the Communist Manifesto. He actually spent several years living in Paris leading up to the Commune and his manifesto was heavily inspired by the revolutionary Parisians who fought against what he called a “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

There’s no hiding the fact that Belleville is still home to the headquarters of the French communist party. It’s a very official and austere-looking building sticking out like a sore thumb on a busy roundabout in Belleville. And inside it pretty much looks like a futuristic Soviet space centre; a textbook example of Soviet brutalist architecture.

The Communist party was founded in 1920 and was once the largest French left-wing party in the country. They only dropped the hammer & sickle symbol from their membership cards in 2013. But before you start imagining the communist takeovers being plotted inside here– despite appearances, today the building actually serves more as a leftist cultural and exhibition centre, and you can even rent it out for events and soirées.

The political party might not exactly live up to its name any longer, but the location of its HQ is no accident and alludes to the very first roots of communism right here in Belleville.

So how does the communism of the Paris Commune relate to the Soviet & Maoist model of communism? It’s safe to say that the Bolsheviks and Maoists lost their way rather early on in their own revolutions. And when Moscow sent troops into Afghanistan, it was basically the final nail in the coffin for communism. Crazed dictators, secret police and cultural repression? That wasn’t exactly the plan of the Paris Commune.

You can find clues to their manifesto today at the Bellevilloise, an old labor cooperative created in the aftermath of the Paris Commune to give working people access to political and cultural education. It was a popular meeting place for the working class and still proudly displays the hammer and sickle above the door. They have a great Sunday jazz brunch, pop-up vintage sales and fairly-priced cocktails on the roof terrace. And while that might seem like it might epitomise the recent gentrification of this neighbourhood, somehow throughout Belleville, there’s this unmistakable sense of rebellion and capacity for resistance and adaptation, which allows the neighbourhood to retain its own political and cultural identity.

Around Belleville, keep an eye out for carvings of ghostly faces on the wall. Get a little closer and you’ll see the words carved around the skulls: “Vive la Commune, 1871”. It means the revolution is still very much alive.