It’s 1970, and for once, the world’s greatest soprano is silent. Interviewer David Frost has just asked her, “Who really is Maria Callas?,” la Divina takes a moment to answer. “There are actually two people in me,” she says, “There is ‘Maria’ and there is the ‘Callas’ that I have to live up to.” But which one must win? She pauses again. The tension-filled interview is the thread of a new documentary by Tom Volf, Maria by Callas, slated for release November 2nd, 2018. But when it comes to the 20th century icons we admire the most, here at MessyNessyChic, we often wonder– do the kids today even know who this is? So while our popcorn is heating up for the film’s release, we thought we’d do a quick show & tell of our fabulous Maria and the cult of ‘Callas’– just in case you might know anyone that needs some ‘filling in’ on one of the greatest divas that ever lived…

Leonard Bernstein called her, “the human Bible of opera,” Aristotle Onassis called her his ill-fated lover, and for her fans around the world she was simply larger than life, an unparalleled talent from…Italy? Greece? Atlantis? Her “regal” accent made her all the more enigmatic.

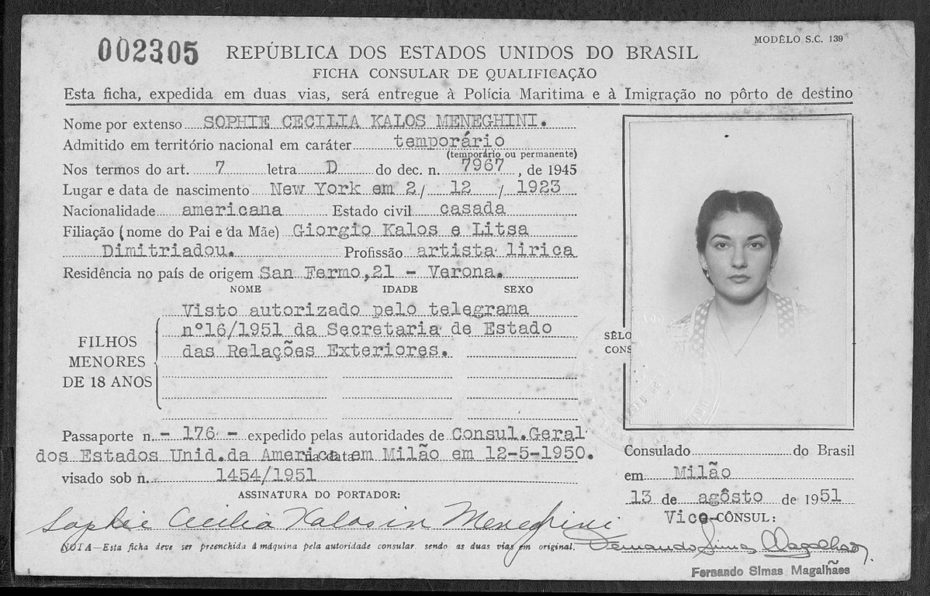

Contrary to what most people believe, she was born in New York City as Maria Anna Cecilia Sofia Kalogeropoulos. Her family had just immigrated from Greece, and set up house in 3-room apartment in Astoria, Queens.“Children should have a marvellous childhood,” she says in the documentary, “and I didn’t.”

“My sister was slim and beautiful and friendly, and my mother always preferred her,” she said, “I was the ugly duckling, fat and clumsy and unpopular”. Maria’s parents fought tirelessly, and berated her at the drop of a hat; for her mother, who’d also wanted a boy as a second child, Maria was born a disappointment. When her parents split ways in 1937, she was devastated to have to move to Athens, Greece with her mother — and her only consolation was singing.

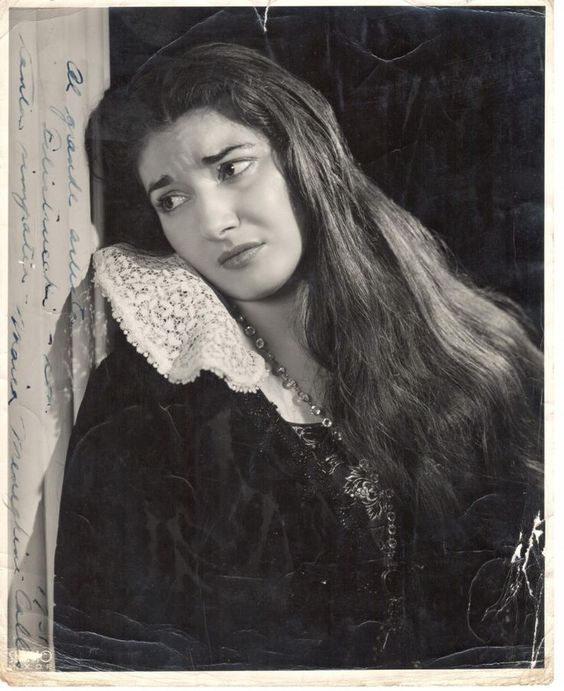

Teenage Maria.

Despite an unhappy home life, she quickly climbed the ranks of the Athens opera scene after her mother had enrolled her in the conservatory. Maria’s first teacher recalled “a very plump young girl, wearing big glasses for her myopia”. A hard-working student, who trained her voice for up to six hours a day, Callas was cast in small roles at the Greek National Opera. De Hidalgo was instrumental in securing roles for her, allowing her to earn a small salary and help her family get through the difficult war years. But opera was a cutthroat business.

“Even in rehearsal, Maria’s fantastic performing ability had been obvious,” said her old classmate, Galatea Amaxopoulou, “and from then on, the others started trying ways of preventing her from appearing.” Despite the harassment of her peers, she left critics slack-jawed after her 1942 role in Tosca. By 1945, at the age of 22, she was back in New York City living with her father, with the Metropolitan Opera impatiently waiting…

She auditioned for the Metropolitan Opera, and was promptly offered a contract and roles in Madame Butterfly and Fidelio, but she declined. It’s been said she turned down the role of Butterfly because she felt overweight for the role, didn’t like the idea of opera in English and was unhappy with the beginner’s contract offered to her.

S0 instead, she went to Italy, and spent the prime of her career there singing at all the major theatres in the country. She met her first husband there, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, an older wealthy industrialist who championed her career in Italy at the prestigious La Scala theatre for 10 years until they divorced in 1959.

The most remarkable thing about Maria is that, for many, her voice wasn’t classically beautiful. “Callas’s voice, considered purely as sound, was ugly,” wrote critic Rodolfo Celletti, “It lacked those elements which, in a singer’s jargon, are described as velvet and varnish… yet I really believe that part of her appeal was precisely due to this fact. Because for all its natural lack of varnish, this voice could acquire such distinctive colours and timbres as to be unforgettable.”

Critic Carlo Maria Giulini also had a fascination with her voice, against his better judgement. “It is very difficult to speak of,” he said, “But after just a few minutes, when you become friends with this kind of sound, [it gains] a magical quality. This was Callas.”

In fact, we don’t recommend reading any further without having some Callas playing in the background…

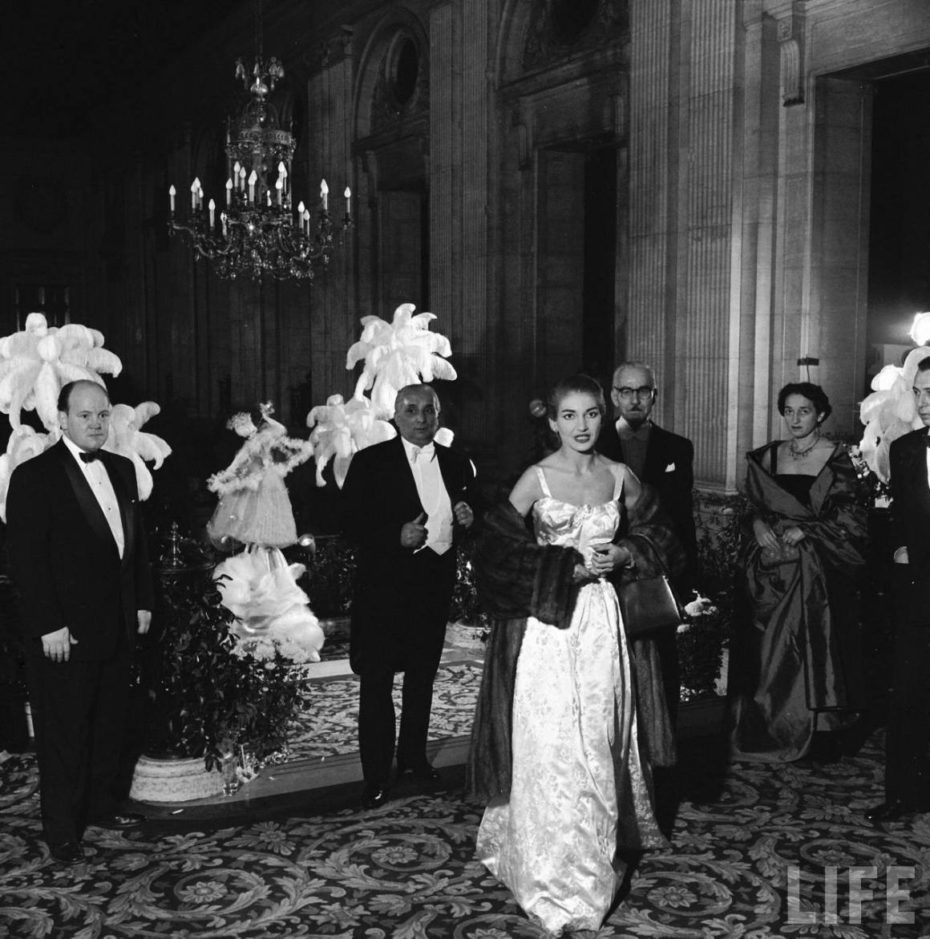

Maria wasn’t just another soprano. She was a new instrument, and everyone was a fan, from Grace Kelly to the Queen of England…

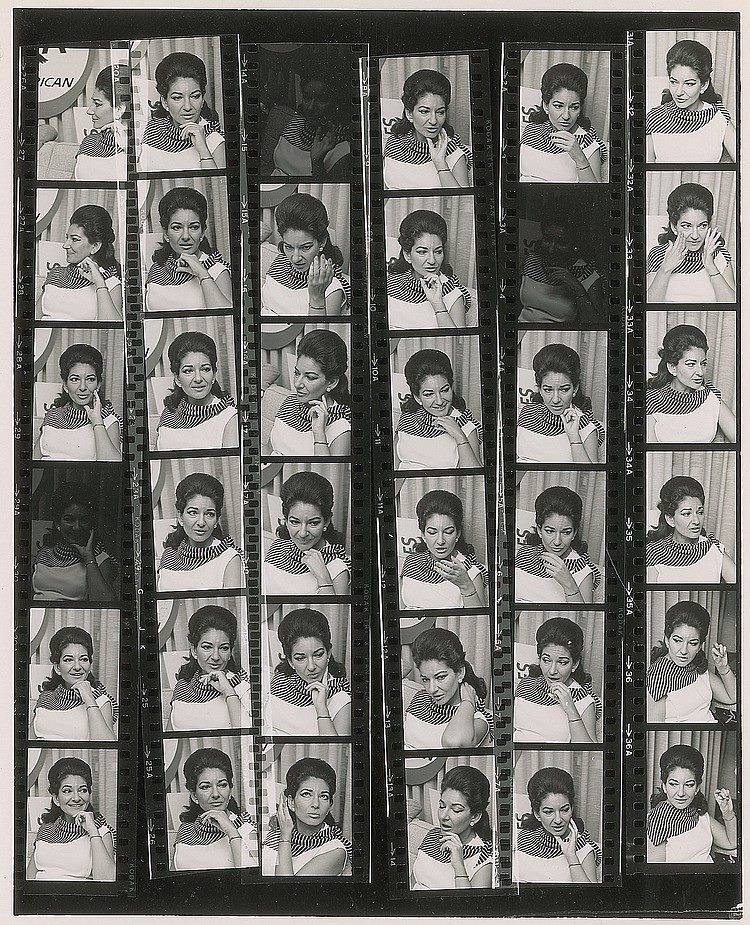

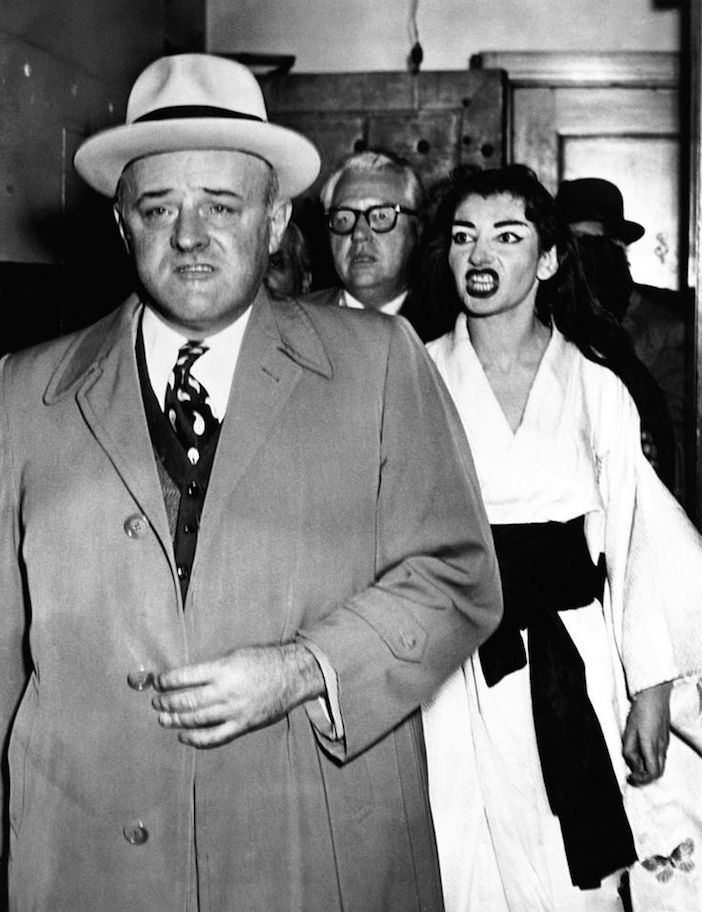

There was no one as simultaneously expressive and strong in character as la Divina. In 2006, Opera Newswrote of her: “Nearly thirty years after her death, she’s still the definition of the diva as artist”. But the press was rarely on her side, and throughout her career she was branded a prima donna, nicknamed the “Tigress”.

Callas was photographed with her mouth turned in a furious snarl as she was served with a lawsuit in 1955

Her media-imposed rival, Renata Tebaldi, was once quoted as saying, “I have one thing that Callas doesn’t have: a heart” while Callas was quoted in Time magazine as saying that comparing her with Tebaldi was like “comparing Champagne with Cognac. No, with Coca Cola.”

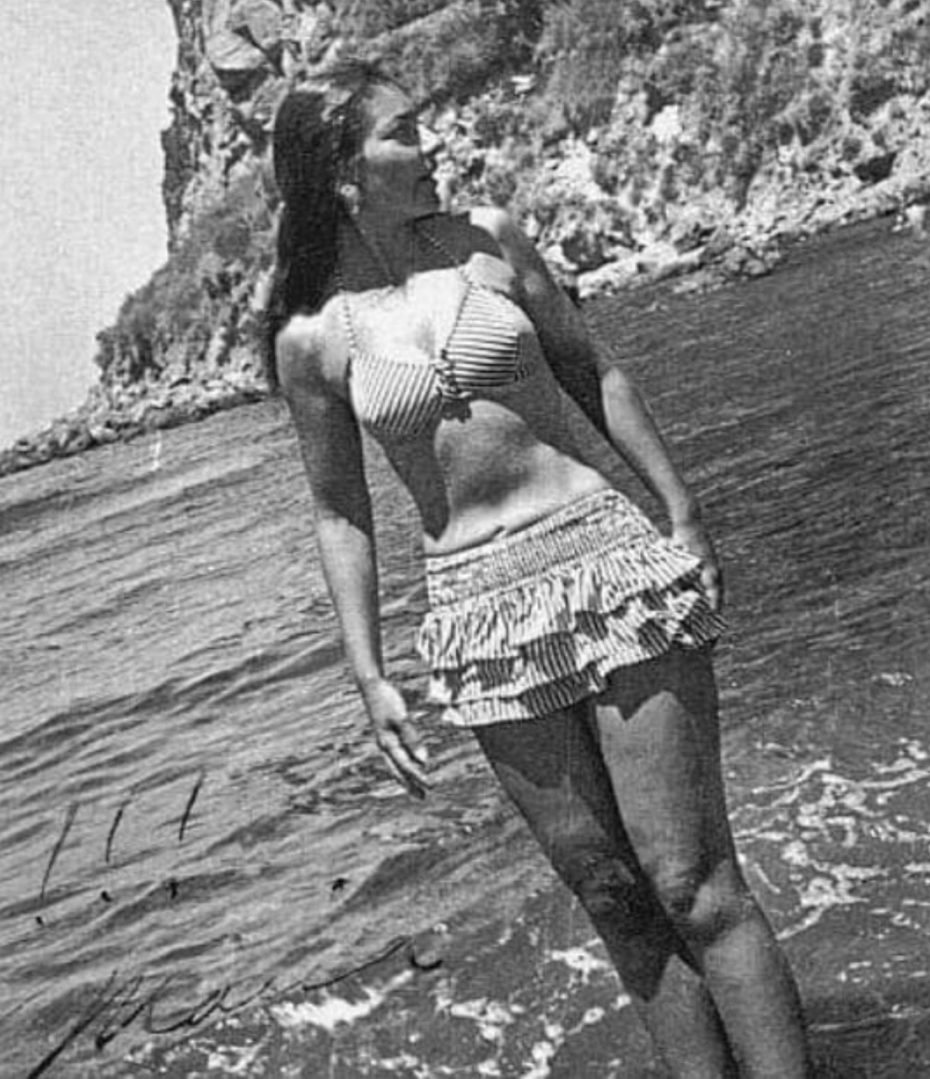

In the early 1950s, Maria underwent dramatic mid-career weight loss, which critics argued later contributed to her vocal decline. Callas recalled: “I was getting so heavy that even my vocalizing was getting heavy. I was tiring myself, I was perspiring too much, and I was really working too hard… And then I was tired of playing a game, for instance playing this beautiful young woman, and I was heavy and uncomfortable to move around.”

In 1953, she lost almost 80 pounds (36 kg). Along with her temperamental behaviour, the press exulted in speculating on Callas’s dramatic weight loss, suggesting she had used all kinds of unhealthy methods to lose the weight. One Italian pasta company even tried to profit from the press coverage, claiming she lost weight by eating their “physiologic pasta”, prompting Callas to file a lawsuit.

Her tenacity saw her relationship major theatres suffer, and both La Scala and the Met severed ties with the opera star during her career. “When music fails to agree to the ear — in other words, soothe the ear, and the heart and the senses, then it has missed its point,” she told Lord Harewood in 1968.

General Manager of the Met, Rudolf Bing said that Callas was the most difficult artist he ever worked with, “because she was so much more intelligent. Other artists, you could get around. But Callas you could not get around. She knew exactly what she wanted, and why she wanted it.” But even during their feud, Bing’s admiration for the singer never wavered, and he admitted to sneaking into La Scala once to listen to her during a recording session. The pair eventually repaired their relationship and Callas returned to the Met for two performances of Tosca.

She had conquered Covent Garden, the Metropolitan, Milan’s La Scala, etc., and for the public she was a bejewelled conundrum; the kind of woman with nerves of ice but a heart that sought relentlessly for love…

–Okay, it’s time for a style intermission, starring some of our favourite diva moments–

Calas and Grace Kelly far left

Kissing Romy Schneider

Callas with Marilyn Monroe in May 1962.

Here she is with Marilyn Monroe on the night John F; Kennedy’s birthday celebration, where she was also set to perform. It’s one of those pictures that blows your mind in retrospect: both Marilyn and Maria would become mistresses of Jackie’s husbands, Jack and Aristotle (respectively).

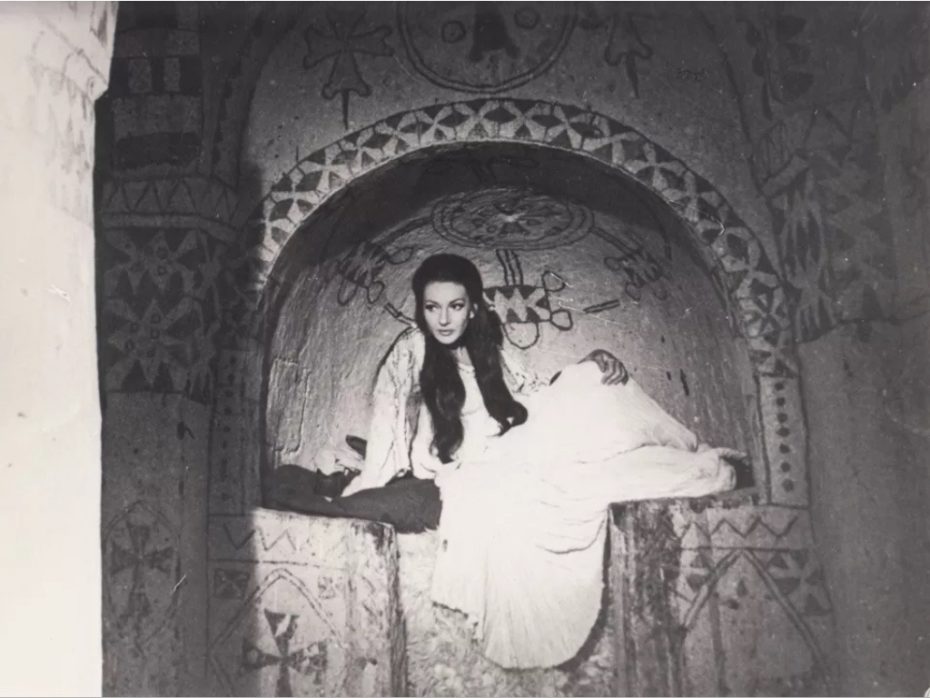

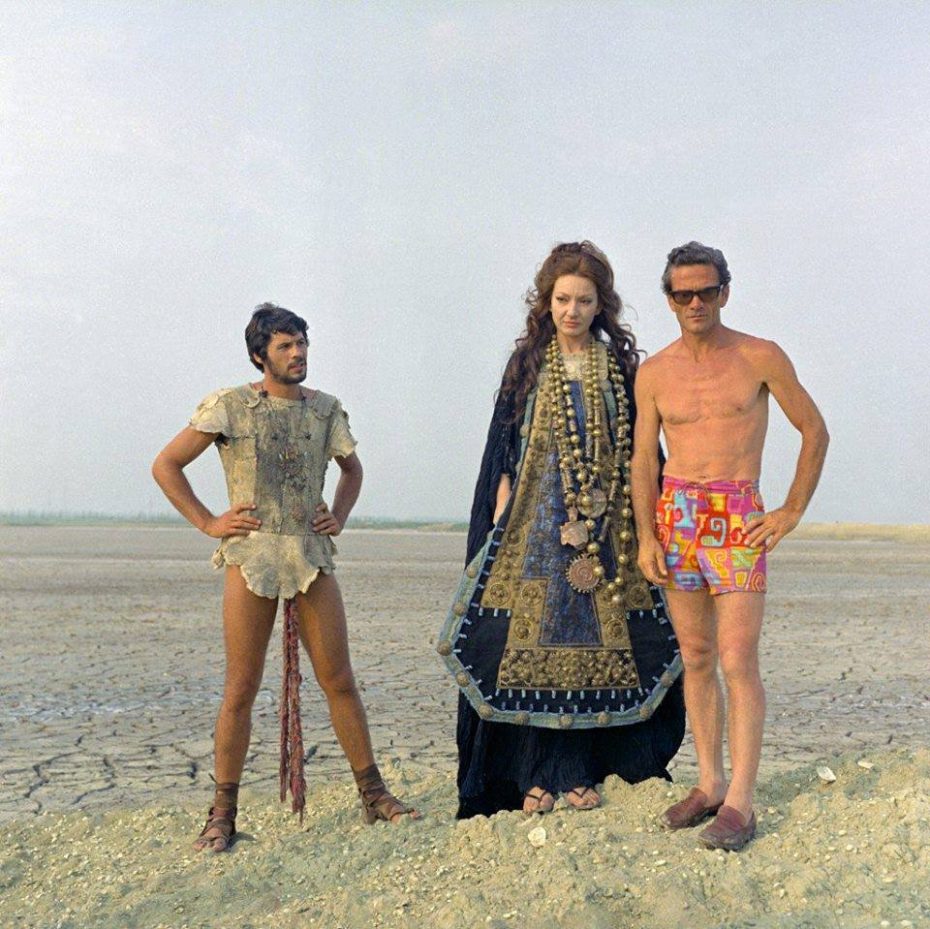

We could unfurl a hefty list of lovers, from singing instructors to movie directors like Pier Paolo Pasolini, who fell for her on the set of 1969’s Medea:

Maria and Pasolini on-set for Medea

But as The New York Times said in 1997, “There were essentially just two men in her life: her husband, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, 20 years her senior, who protected like a father and nurtured her career, and Aristotle Onassis, who lured her with promises of luxury and marriage.” Her love affair with Aristo, as she called him, was born on a yacht in 1959. Naturally.

Maria in the swimming pool of the Onassis yacht

Callas left her second husband for her fellow Greek Aristotle in November 1959 and for the next 10 years, effectively abandoned her career. In 1968, Onassis left a heartbroken and humiliated Callas for Jacqueline Kennedy. He thought that by marrying the First Lady, she would be his entree into American business life. Onassis told Maria when he admitted the affair: “I love you, I need Jackie.” But even while Aristotle was with Jackie, he frequently met with Maria in Paris, where they resumed what had now become a clandestine affair. When Onassis died, Maria didn’t go to the funeral, saying: “How would it look — his two wives by his side?”

Maria did end up back on stage, and used her career to heal her heartbreak. It was where she felt she was always destined to be, she explained, not as a woman but as the main instrument of an orchestra: the Callas.

Interest peaked? Put on your best cat-eye and watch the trailer below:

All images sourced from the Maria Callas Tumblr.