The truth is, surrealist art was a man’s world. Its founder, André Breton was an unrepentant misogynist who believed women could not hold a central position in art. Dali too, could be patronising of his fellow female surrealists. When asked about our favourite bohemian queen of Paris, Leonor Fini, he said of her work, “Better than most, perhaps. But talent is in the balls”. So it should come as no surprise really, that it’s taken us this long to discover Maruja Mallo, one of the leading contributors to the Spanish Surrealist movement who was just as fascinating as her friend and fellow Spaniard, Salvador Dali.

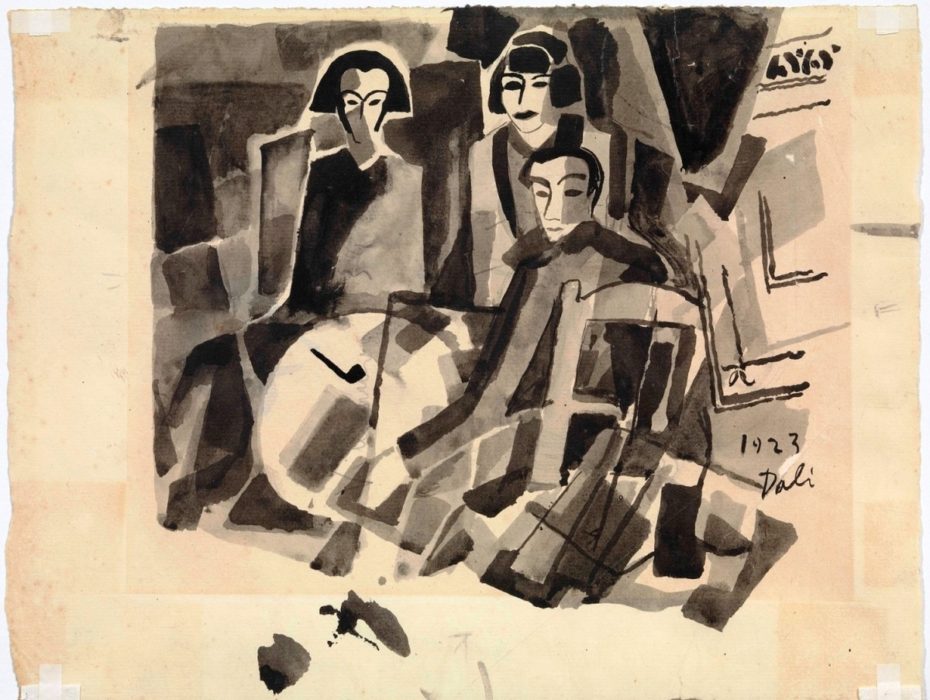

Mallo and Dali became friends at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid in the 1920s. This was the time when she would become part of the “Generation of ’27” an influential avant-garde group of poets that arose in Spanish literary circles during the mid 20s– the answer to Paris’ Lost Generation and England’s Bloomsbury group.

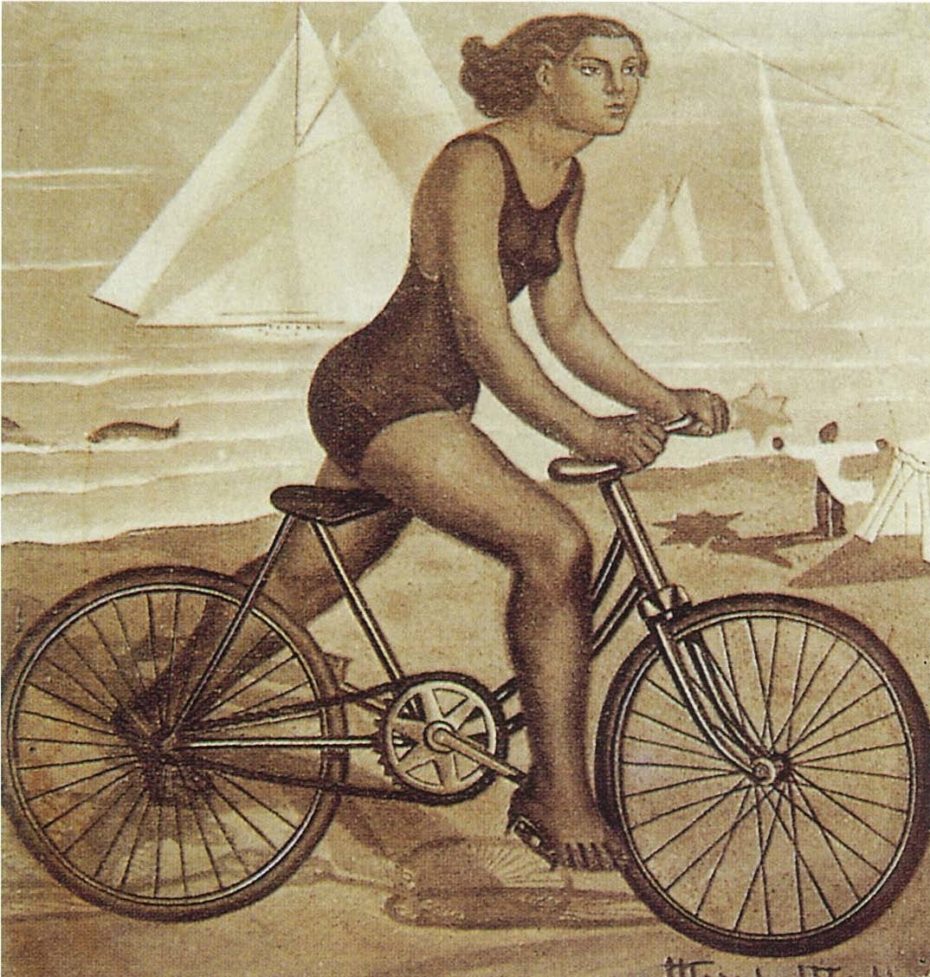

Salvador Dali and Maruja Mallo, Café de Oriente 1923

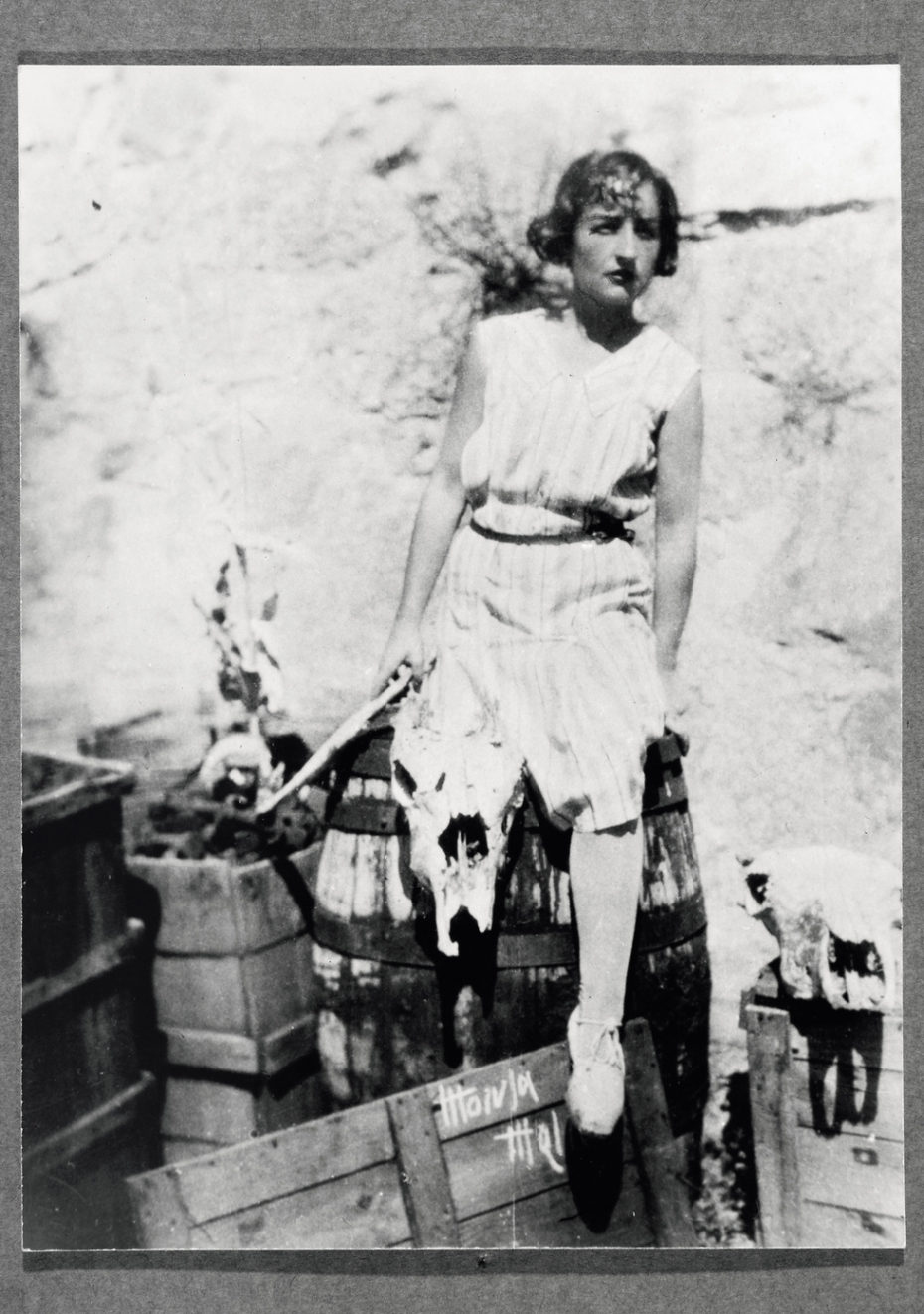

Mallo was one of few women in the group and had open but intense relationships with several of the members including poets Pablo Neruda, Rafael Alberti and Miguel Hernández, affairs that would later eclipse her own work. But during her prime, she was constantly praised by the major art critics for her brilliant skills and her audacious innovations.

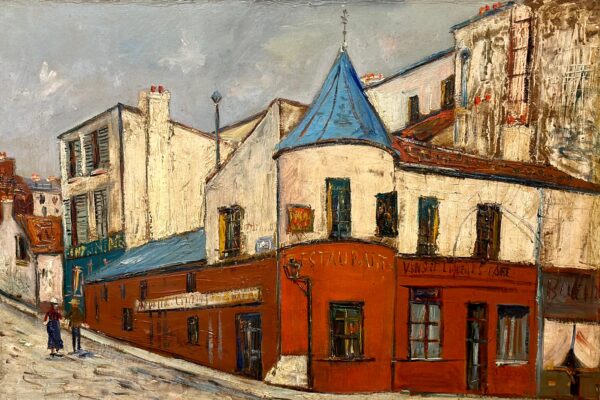

Ramon Gomez de la Serna, the high priest of the literary salon “El Pombo,” called her “the painter of fourteen souls,” and the Pope of the surrealists, André Breton himself acquired one of her works at a Paris exhibition in 1932. So what happened for her name to be forgotten?

At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, devastated by what she perceived as the end of the Republic and the demise of freedom, she exiled herself to Argentina. The decision saw her male counterparts of the Surrealist movement isolate and even boycott her, erasing her from the history of the Spanish avant-garde. From then on, Mallo’s name was only mentioned in Spanish art history for her scandalous affairs with the key vanguardists, labeled as a mere “mascot” or “muse” of the Generation of 27.

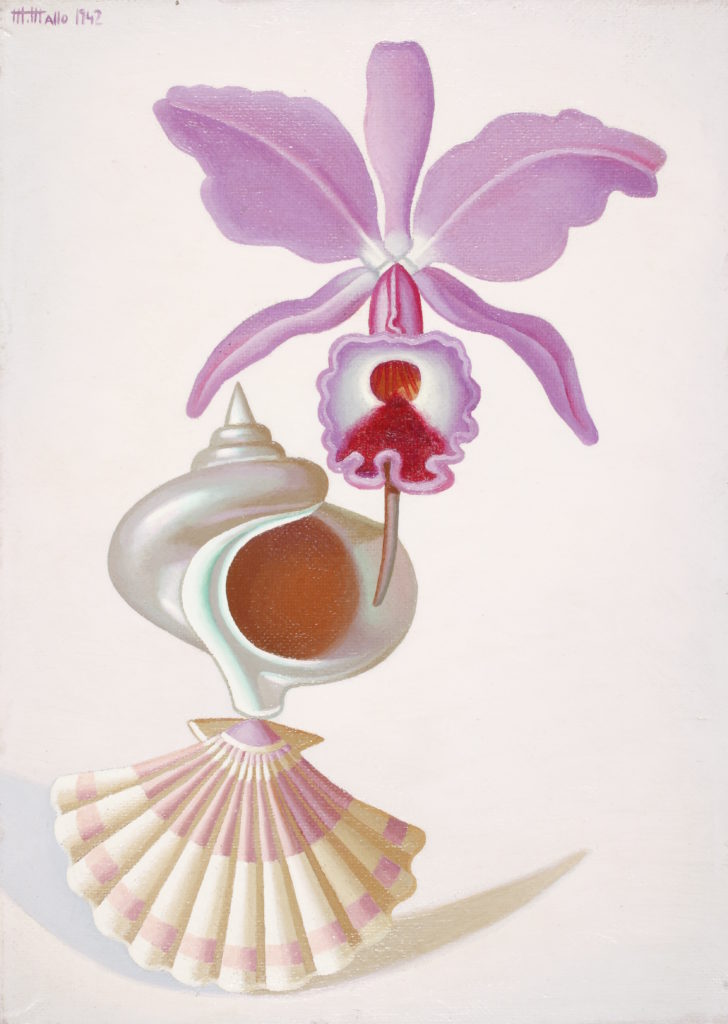

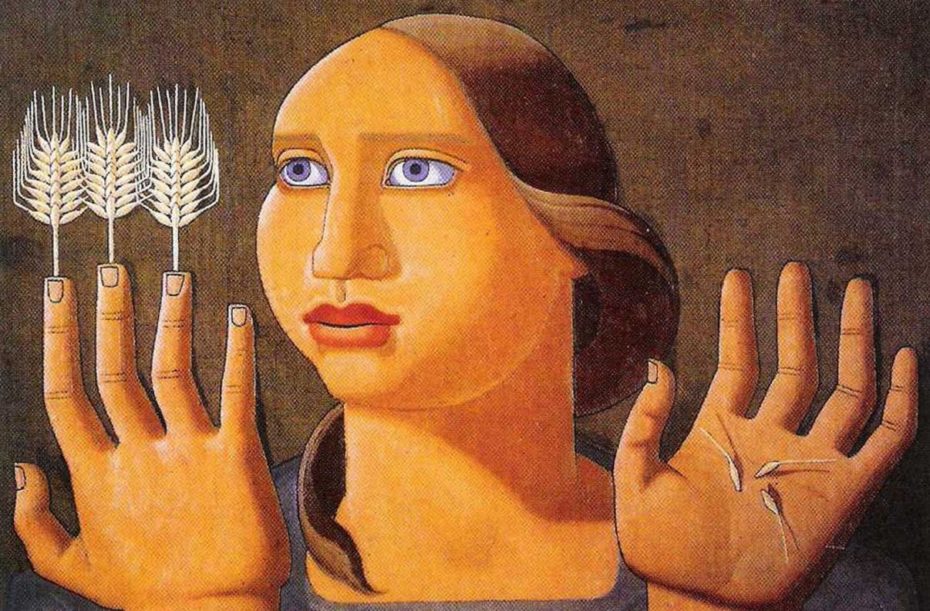

During her time in exile, she travelled incessantly, made new friends, like Andy Warhol and participated in the cultural and social life of New York, Paris and Rio. She gradually replaced her socialist subject matter with a language that exalted the female body: feminine oceanic motifs and mythological female figures, and rarely painted male figures at all in the 1940s.

When she returned to Spain in 1962, she realized that the world she knew there had disappeared, her friends had died and the press didn’t understand her, questioning her credibility and often mocking her increasingly erratic behavior and unconventional attire in the gossip columns. She continued to make public appearances, as Dali did, until her final days, and was often photographed at events in her 80s, a petite eccentric wearing her signature fur coat, outrageously made-up, and a crowd of onlookers staring at her.

But here we are, decades later, in the midst of the #MeToo and look who’s found her way onto our radar. In fact, we’re pretty pleased about the fact that not only is a rare show of paintings by Maruja Mallo on view in New York City until November 17th at the TriBeCa gallery Ortuzar Projects, but our other favourite forgotten female surrealist, Leonor Fini is also currently having an exhibition at the Museum of Sex, NYC until March 2019. Looks like we’re getting somewhere.

The New York Times points out that Surrealism was a product of Europe experiencing terrible violence and great political upheaval, but “over time the movement’s edge softened, until it was reduced to a handful of visual clichés: melting clocks and faceless men in bowler hats. But perhaps now — as women’s truths are being questioned and our reproductive rights threatened — true Surrealism, especially as interpreted by a woman artist, is worthy of a second look.”