© Anthony Saroufim

Love it or hate it, brutalist architecture has an unavoidable presence in every major metropolis– even Paris. In fact, the French capital is something of a haven for futurist concrete architecture. Brutalist boomed here during the 60s and 70s in response to Modernism’s utopian vision, and after Haussmann, came superstar architects like Le Corbusier and an ambitious period of experimentation. A young photographer has been quietly weaving in and out of the city’s misfit icons, from the jagged courtyard of les Orgues de Flandre in the 19th arrondissement, to the jaw-dropping Panopticon of “Abraxas”, the real-life Hunger Games mini-village, that dwells on the outskirts. Anthony Saroufim opened up to us about why the ‘Brutal’ side of Paris has captured his heart…

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

Born in Beirut, Saroufim moved to Paris to continue his studies in design after graduating from the Lebanese American University. Having lived in the shadow of war and violence in Beirut, the notion of how a city could reconstruct itself socially and physically through architecture fascinated him.

There’s a creeping feeling that, for many of these buildings, the line between unity and uniformity somehow became blurred and dystopian. “All the general public sees now is dirty concrete,” he explains when asked about Paris’ greying monoliths, “scuffed, tired aggregate; it is also associated with authoritarian government facilities such as council offices, police stations, prisons, public schools, hospital wards and public housing.”

© Anthony Saroufim. Abraxas, the real-life Hunger Games city

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim. Noisy-le-Grand parking garage

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

Beauty was never the point of Brutalism, says Saroufim. Not in the traditional sense. “Brutalism occupies a moment of transition between modernism and post-modernism,” he says, “[…] building techniques were cutting construction times, cutting costs and cutting-edge. With money to be made on a grand scale, architects’ egos soared. The future was to be guided by their creative vision and their self-reverence. Their constructions drew attention to their materials, deconstructed the excess of detail and celebrated the fundamentals of the building itself. It should challenge you and make you ask questions. You don’t have to like it. That’s ok.”

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

Les Arcades du Lac by Bofill. © Anthony Saroufim

Architect Ricardo Bofill has created perhaps the most iconic Brutalist structures in the city at Noisy-le-Grand, a suburb that’s fallen into a high rate of crime and poverty despite the utopian philosophies embedded in its blueprints, which sprawl across water or form tremendous, wheel-like structures.

Les Arcades du Lac by Bofill. © Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

Saroufim’s architectural quest has also taken him outside of Paris, and into new cities and new buildings that aren’t always Brutalist in the traditional sense, but always represent a unique approach to public space. Like the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, Spain, which looks like something from a space age Atlantis:

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

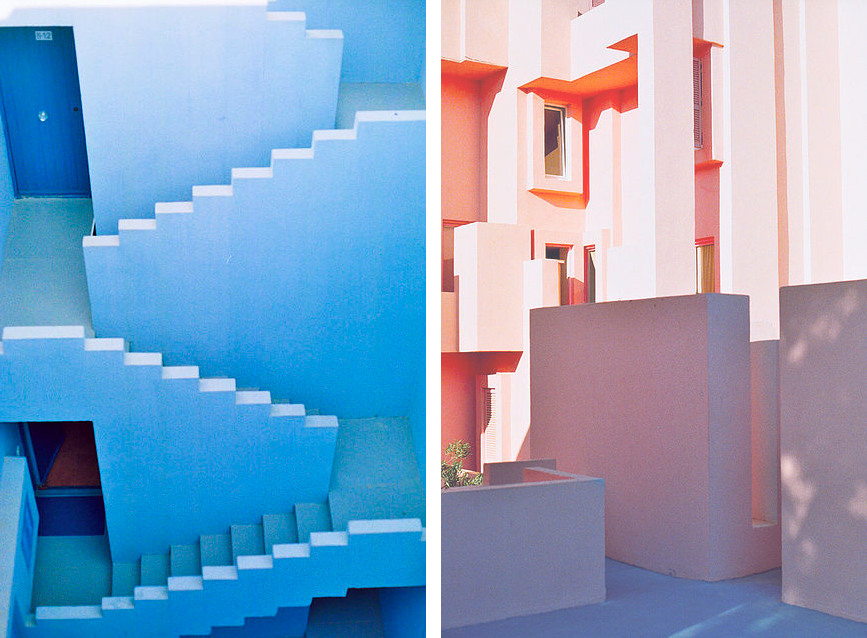

Or to Murali Roja, Ricardo Bofill’s “Red Wall” that represents a sunnier side of the Brutalist architect that looks like a cotton candy jigsaw puzzle in Spain’s Calpe:

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

Back in Lebanon, the contrast between what Brutalism has tried to achieve (i.e. anti-bourgeois, utopian spaces) and the reality of a country with heavy war-time baggage is still very visible. Consider Rashid Karami Fairgrounds, one of the many uncompleted projects by Oscar Niemeyer. The site is essentially an empty playground spanning over 10,000 hectares:

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

© Anthony Saroufim

Then there’s “The Egg.” Built in 1965 in downtown Beirut by Joseph Philippe Karam, Saroufim explains that it was part of the Beirut City Center that became more of a witness to the turmoil of the city than a centre in its own right. “With the beginning of the war in 1975 “The Egg” lost its spectators only to become itself the spectator of the city’s evolution,” he says, “The theatre witnessed Beirut in its different phases and adapted to its changing theatrics…during the fifteen year period of the civil war it was used as a bunker, and later on, since the post-war reconstruction period, the building became a monolith in the city.”

© Anthony Saroufim

That’s the beauty of the Brutalist world as it’s captured through Saroufim’s lens: it tells a story that’s not always easy to see, but one that’s in constant evolution and, above all, begs us to think about the spaces we call home.