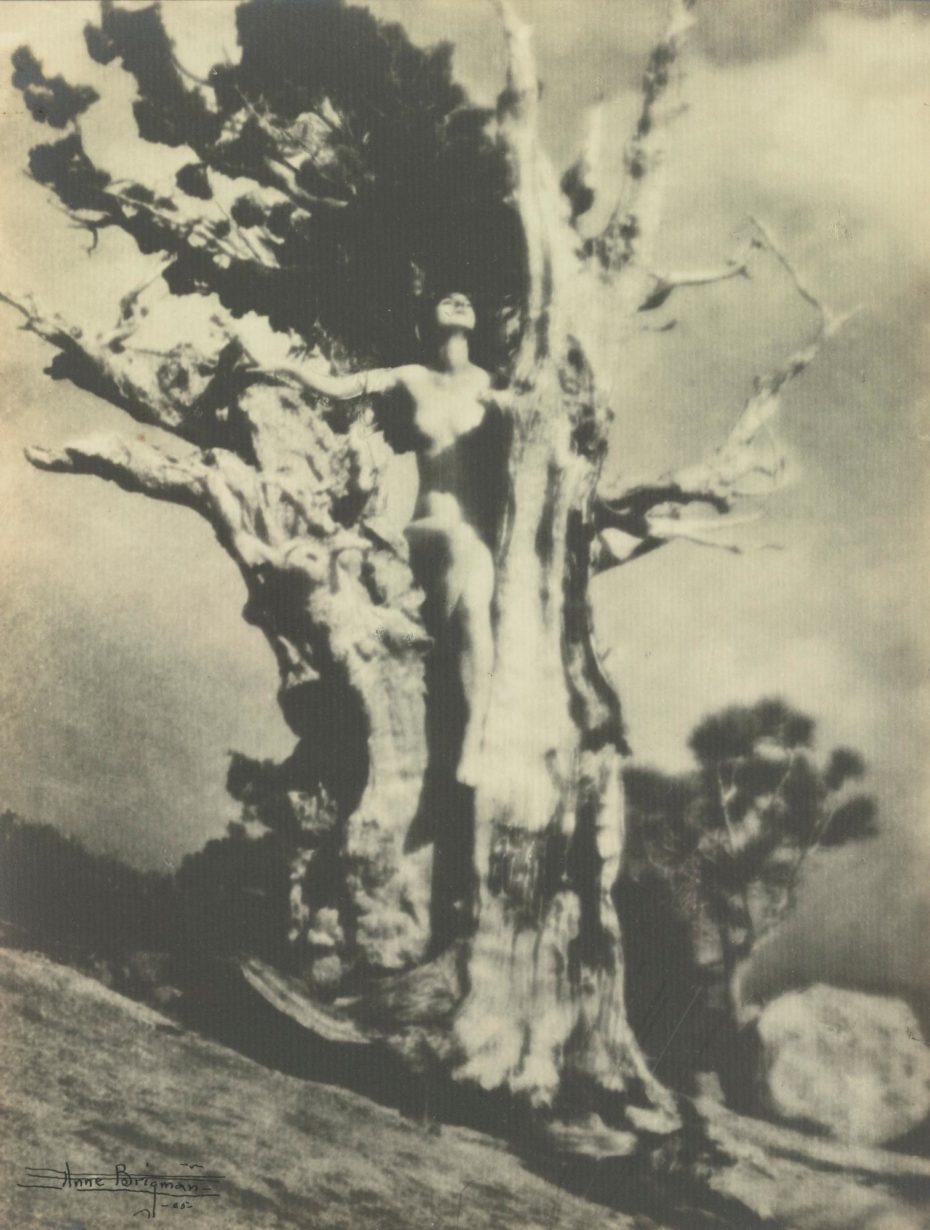

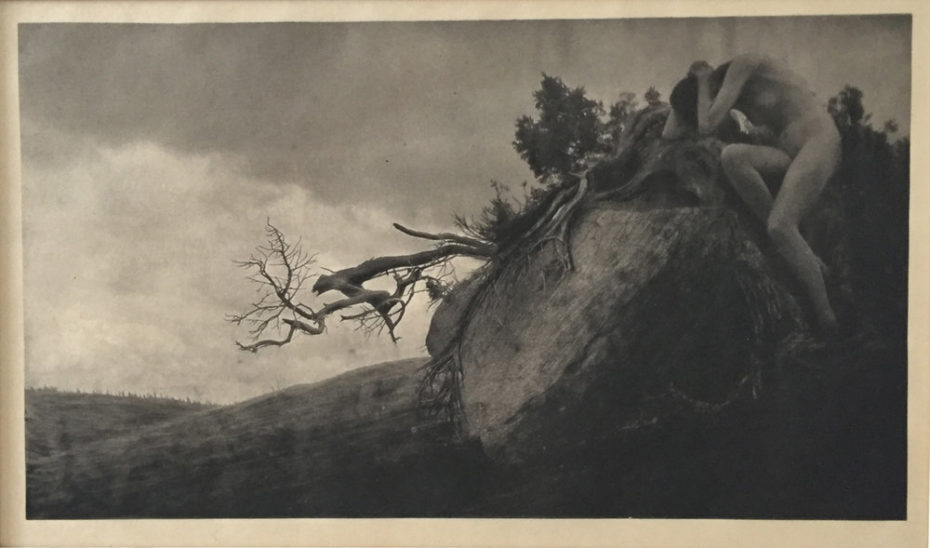

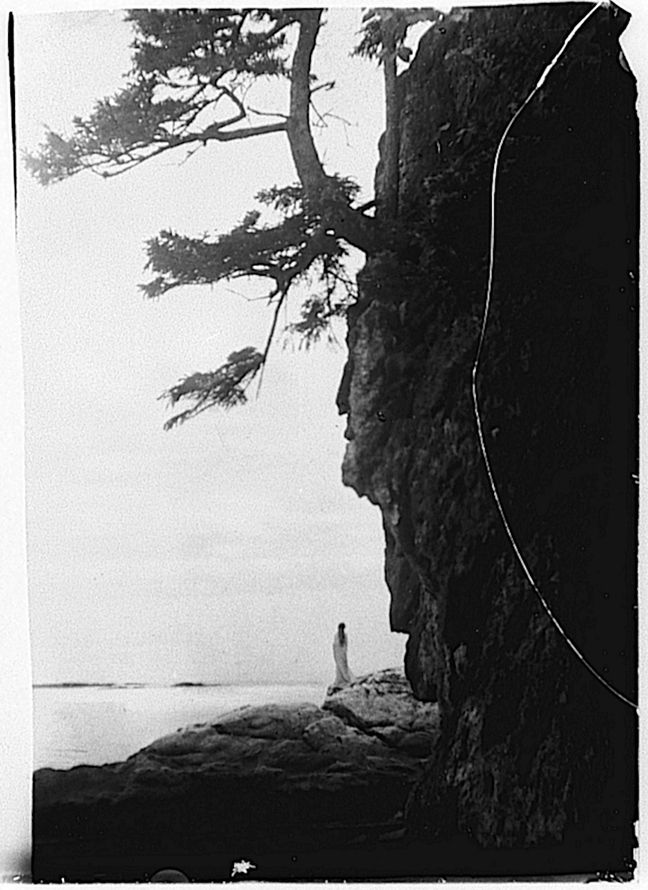

The Soul of the Blasted Pine, Self-portrait 1908, Anne Brigman

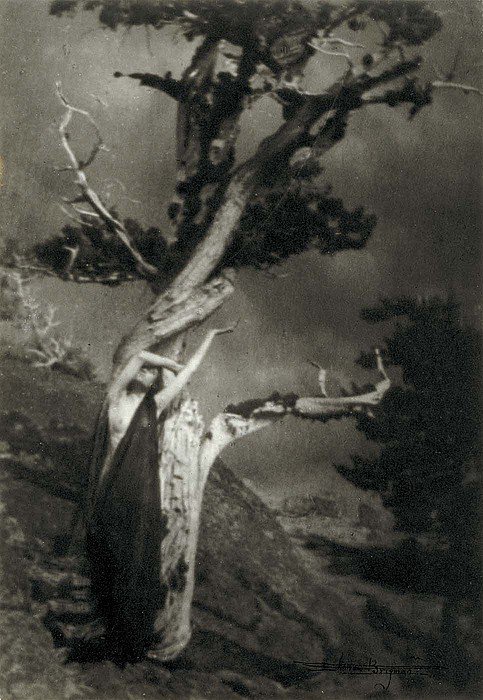

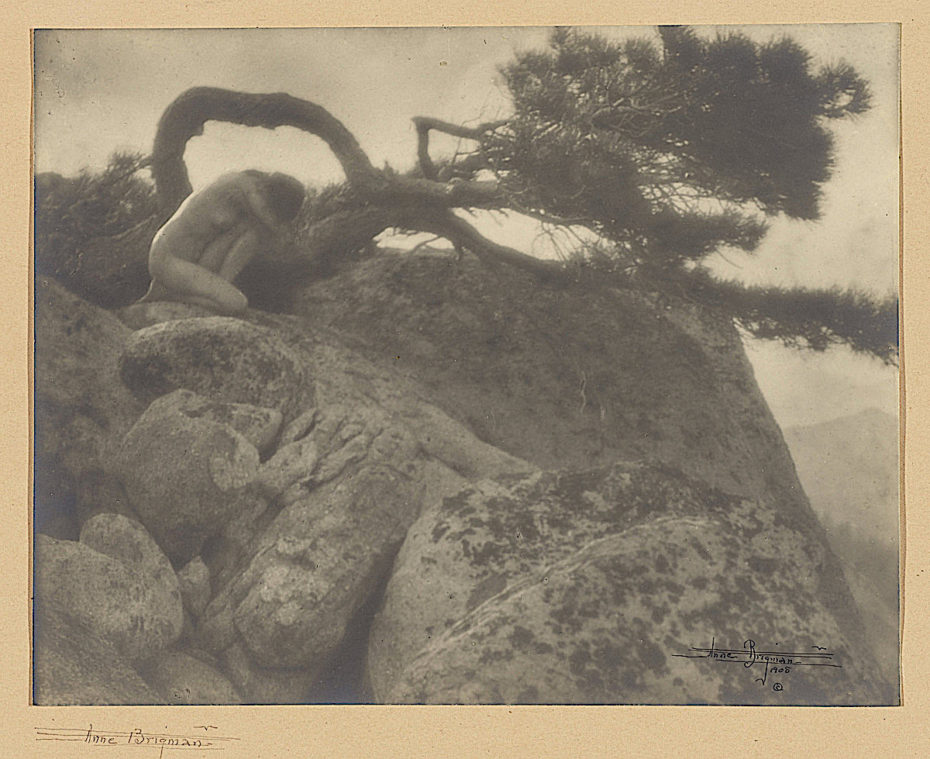

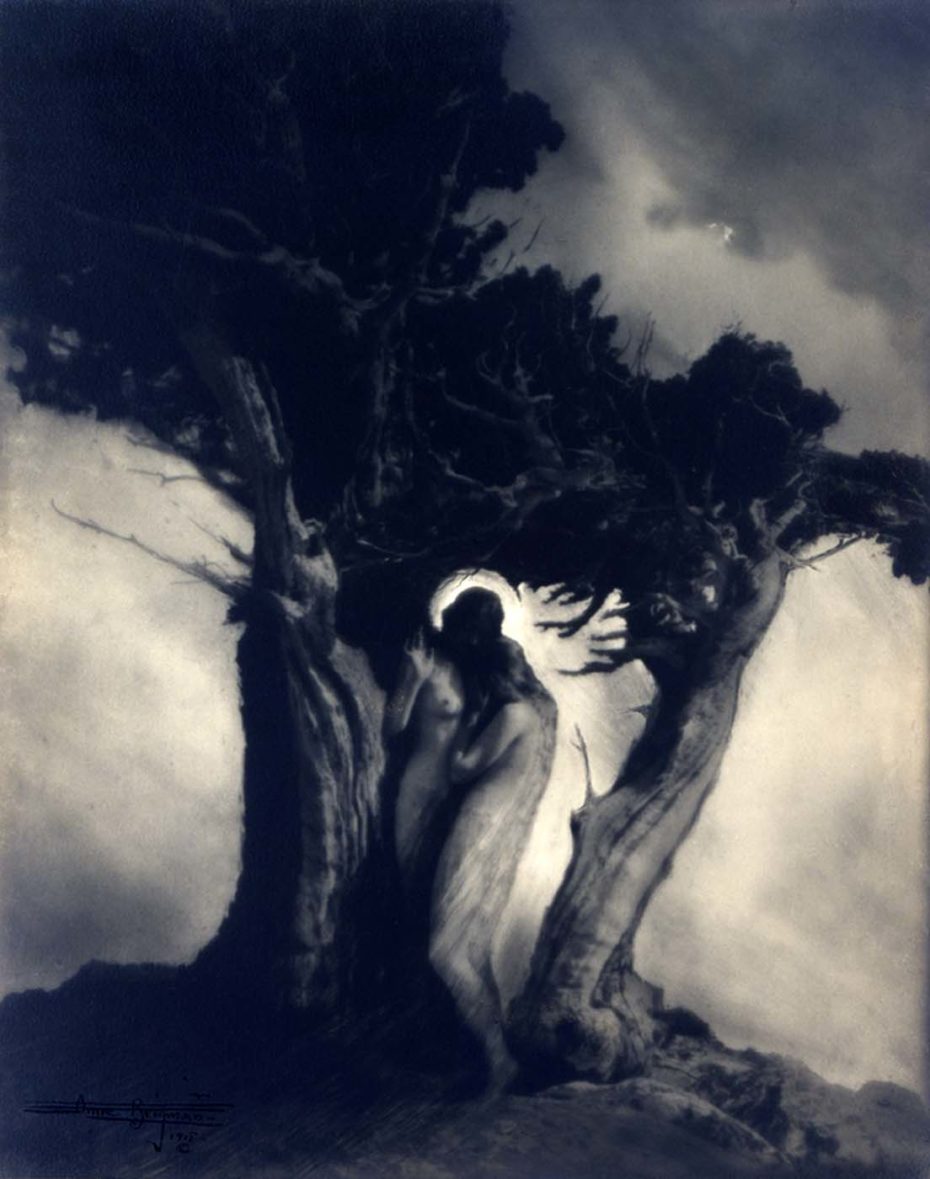

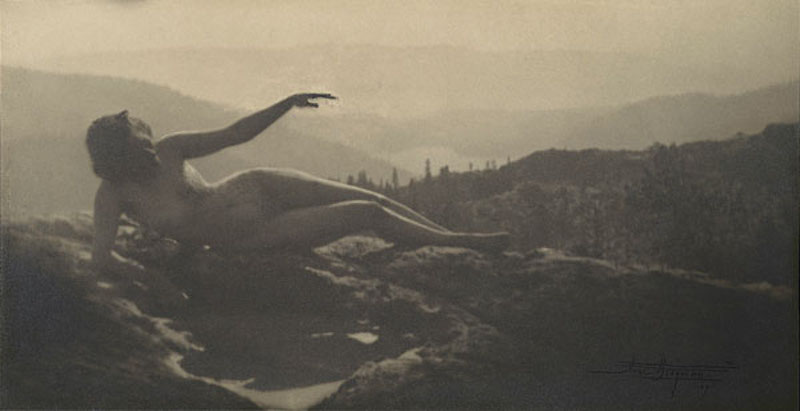

Anne Brigman was turning up her selfie prowess about 100-years before the rest of us. For one, she was never the stoic, buttoned-up type, and felt more at home on a mountaintop than with a roof over her head. When Brigman stepped inside the lens of her camera, the result was a ‘selfie’ that looked like an Old Master’s painting come to life– and, might we add, with some serious ‘special effects’ long before Photoshop was available. She’d melt her body into the heart of a lightning-blasted pine tree, or twist like the limb of a cracked oak, all through the magic of photo manipulation before the digital age, when tricking the human eye was a feat of magic. Put yourself in the shoes of a human from 1907, and you can see why Brigman’s gauzy finishes, high contrast, and ethereal surroundings transformed her into a Pagan goddess amongst mortals…

Anne Brigman

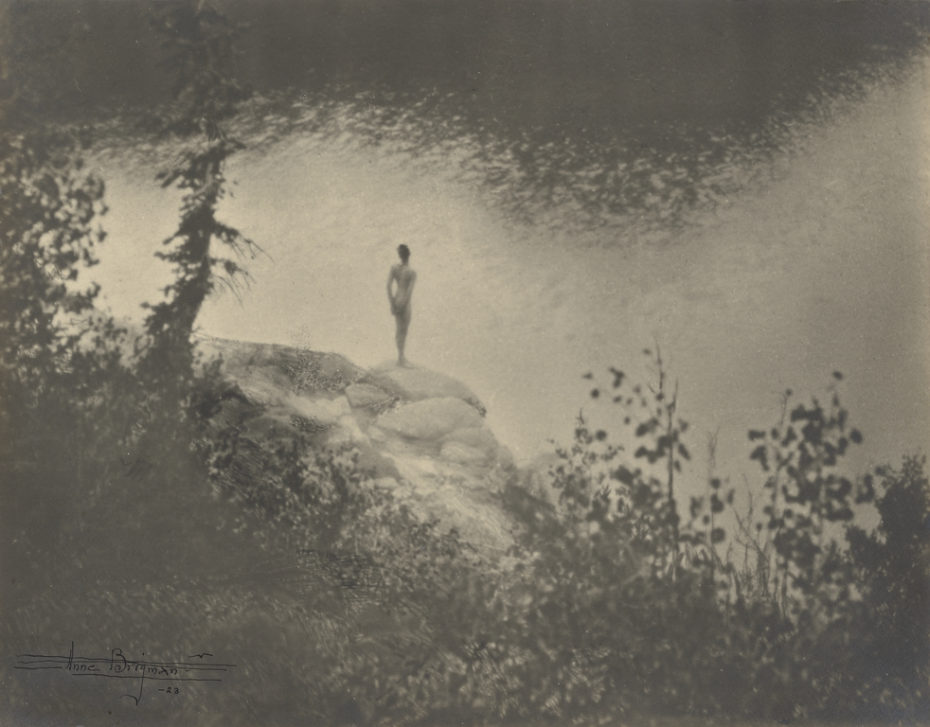

“Although the term feminist art was not coined until nearly seventy years after Brigman made her first photographs,” explains John Hawley Olds of the LaGatta Gallery, “the suggestion that her camera gave her the power to redefine her place as a woman in society [makes] her an important forerunner in the field. To objectify her own nude body as the subject was groundbreaking; to do so outdoors in a near-desolate wilderness setting was revolutionary.”

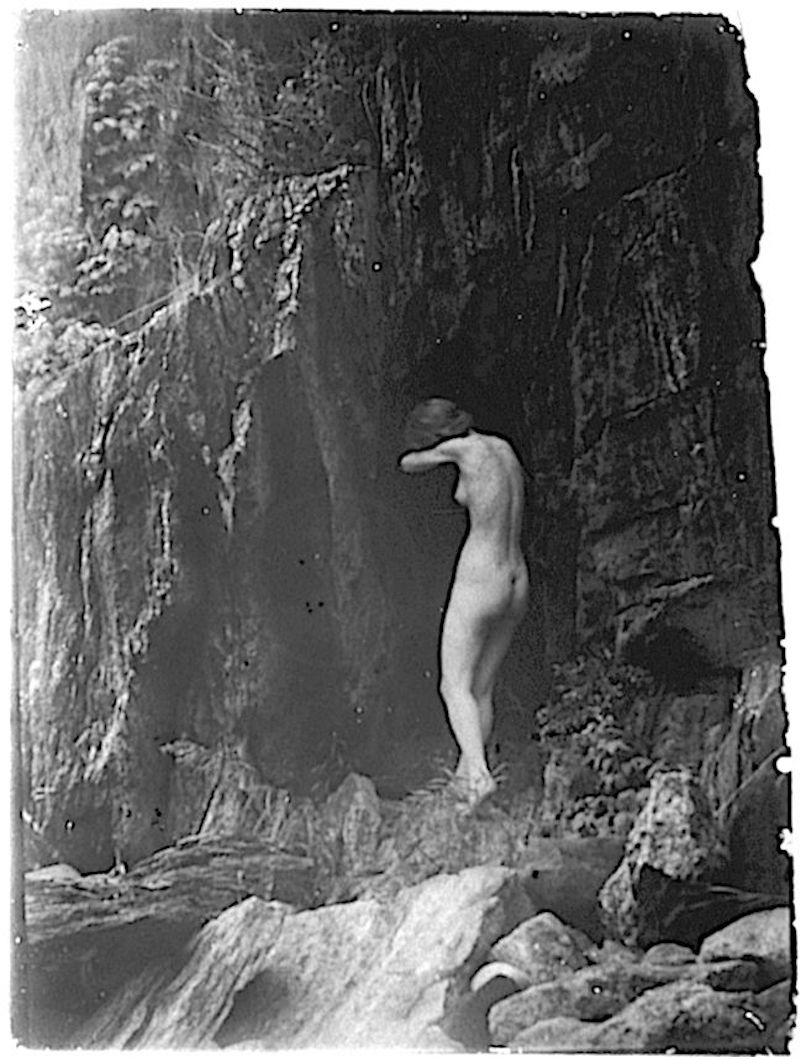

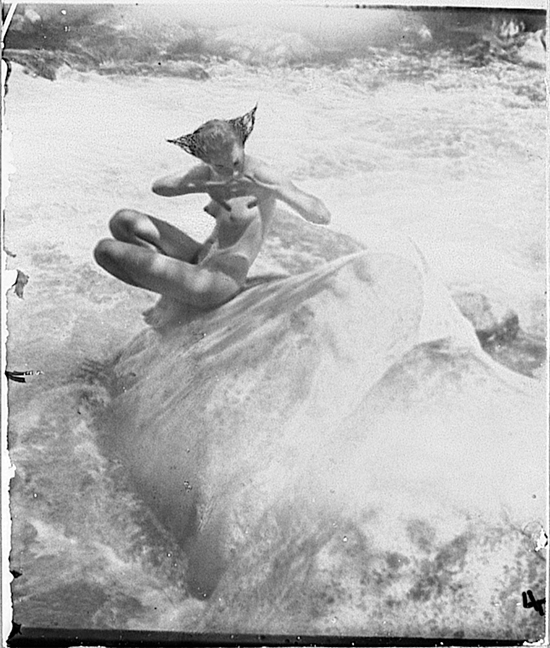

The Bubble; 1909, Anne Brigman

The Bubble; 1909, Anne Brigman

The Dying Cedar, 1906, Anne Brigman

Figure in a Landscape, 1923

She was the leading lady of the early 20th century artistic movement called “Photo Secession”, a school of bohemians, part of a larger, international aesthetic movement called Pictorialists, whose dramatic eye for photo manipulation shocked the mainstream photography community, but sent everyone else into a new way of daydreaming.

Anne Brigman

In the wake of an industrializing world, there was nothing more radically symbolic and pro-romance than reclining naked on a log in the Sierra Nevadas. That it should be Brigman and her posse of mountaineering ladies posing in the wild, makes it a bold stroke of feminism. Not to mention, that it kind of makes her the first California hippy queen…

Anne Brigman in Doorway of Her Studio. c. 1908. MoMA.

She was born in Hawaii in the winter of 1869, the oldest of eight children, and moved to Los Gatos, California with her family when she was a teen. There, she wrote poetry about “wild trees”, painted, and acted in local productions.

Anne Brigman

Anne married a sea captain, Martin Brigman, and often travelled with him as far as the South Seas. The story has never been confirmed, but according to her friend and fellow photographer Imogen Cunningham, on one of Brigman’s voyages with her husband, she injured herself so badly, it resulted in the removal of one of her breasts.

Anne Brigman

By the turn of the century, Anne was divorced and living in California with a dozen birds and her dog, Rory. She was in many ways, “the ‘new woman’ of the period”, says Jane Gover, author of The Positive Image: Women Photographers in Turn-of-the-Century America, “and retained few Victorian values in her personal and professional life.”

The Water Nixie, 1914, Anne Brigman

The final product of Brigman’s work always looked effortless, like candid snapshots of wood nymphs taken at whim, but the process was painstakingly long; not only did she have to venture out into the wild for her images, but she spent ages touching up superimposed negatives with paints and pencil. Luckily, it paid off, and she became a real sensation on the Bay Area art scene.

Anne Brigman

We’ve also never seen someone wax so poetic about a camera as in Brigman’s 1926 essay “The Glory of the Open”:

“I looked at my 4×5 Korona View camera and the beloved Smith lens — NO! I was tired. I wanted to go and be free. I wanted the rough granite flanks of the mountains and the sweet earth. I wanted the stacatto song of wing around rocks and juniper branches. The little No. lA Ansco, with its 2 l/2 x 4 1/4 film, would do.” – Anne Brigman

Anne Brigman

Her work was not always met with such enthusiasm however. Her most recognised piece, The Soul of the Blasted Pine, was criticised and removed from a public exhibition in 1908; Brigman herself was called a vulgar and “scrawny dame”. The following year, Alfred Stieglitz, the man credited with making photography an accepted art form, published her photographs in the quarterly photographic journal, Camera Work, elevating her as one of the most important of the Photo-secessionists and as a woman artist who would reveal the secret of woman`s sexuality. Brigman went on to use her new-found celebrity platform to speak to the press about the liberation of women in a male-dominated society.

Storm Tree, 1915, Anne Brigman

By the 1930s, her declining vision forced her to abandon professional freelance photography and began writing poetry. She put together a book of her poems and photographs called Songs of a Pagan, but just as she’d found a publisher, World War II broke out and the book was not printed until 1949, the year before she died. There are 5 copies available on Amazon.

Anne Brigman

Brigman died in El Monte, California, 1950, but the spirit of her work lives on in the work of artists who continue to explore and master the art of self-portraiture, like our talented friend, photographer and co-inventor of the cinemagraph, Jamie Beck…

You may recall us drooling over her photography and Instagram account, @annstreetstudio, in a past article. Beck’s self portraits and still-lives look like they were plucked from the walls of Louvre, and are totally akin to Brigman’s take on highly-stylised photography. We talked to her about what Brigman’s work means to her, and what it’s like to strengthen one’s identity as a woman in photography.

She brings up Brigman’s use of her own celebrity to carve out a space for women in the arts that, she says “We are STILL, 100 years later fighting, and funny enough, her pictures are actually more liberating than what we are allowed today to show and share as women. The nipple-less body for example, on Instagram. The slut-shaming on social media. The inequality in the value of women’s work to men’s, still…. and a woman’s word to a man’s (Dr. Ford’s Senate testimony back in the States). The purpose of my work comes from a place of tearing myself down to the basics, stripping away the logos, the cultural identity that I have projected on to myself as a woman about how I’m supposed to look and be clothed. And perhaps, most importantly finding the value not in what I adorn my body in but what I am made of.”

Visit Jamie’s blog, Ann Street Studio, here, and visit some of Brigman’s work at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles on permanent display.