William Mortensen

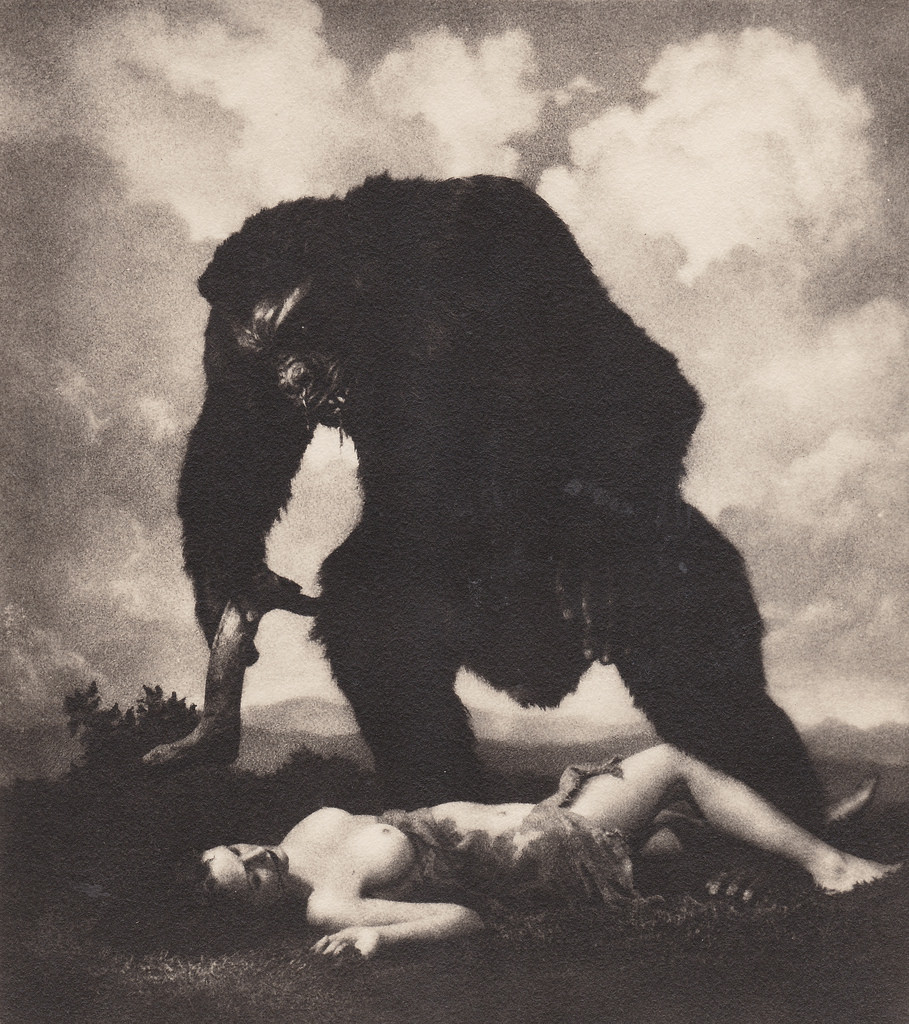

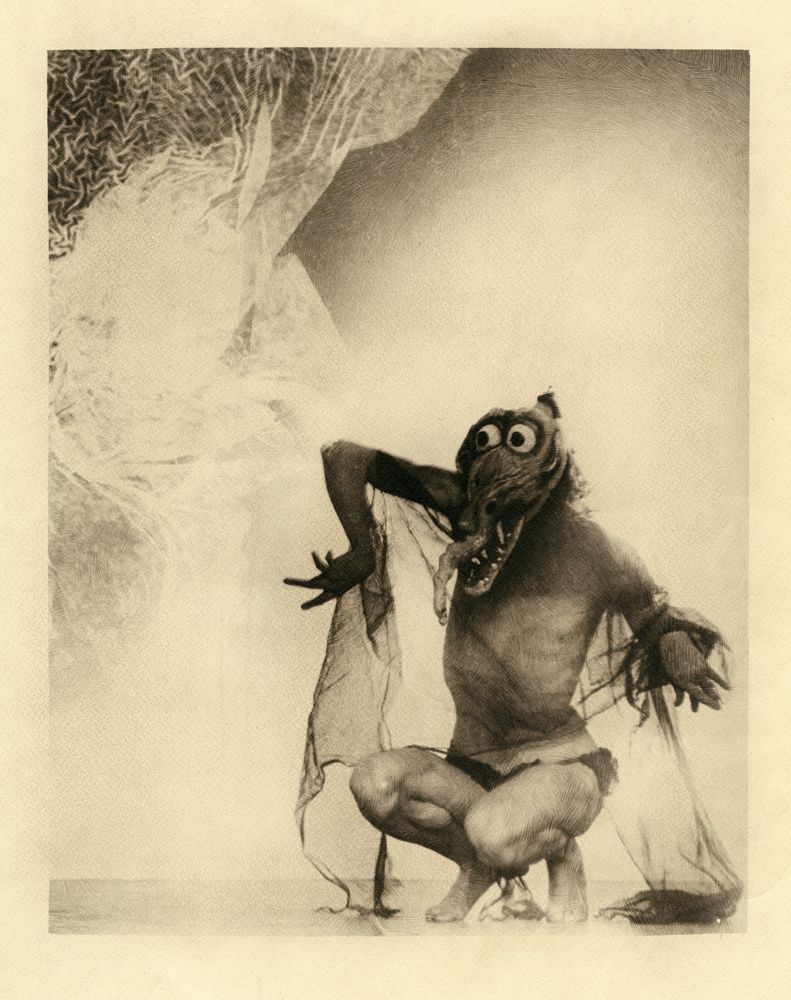

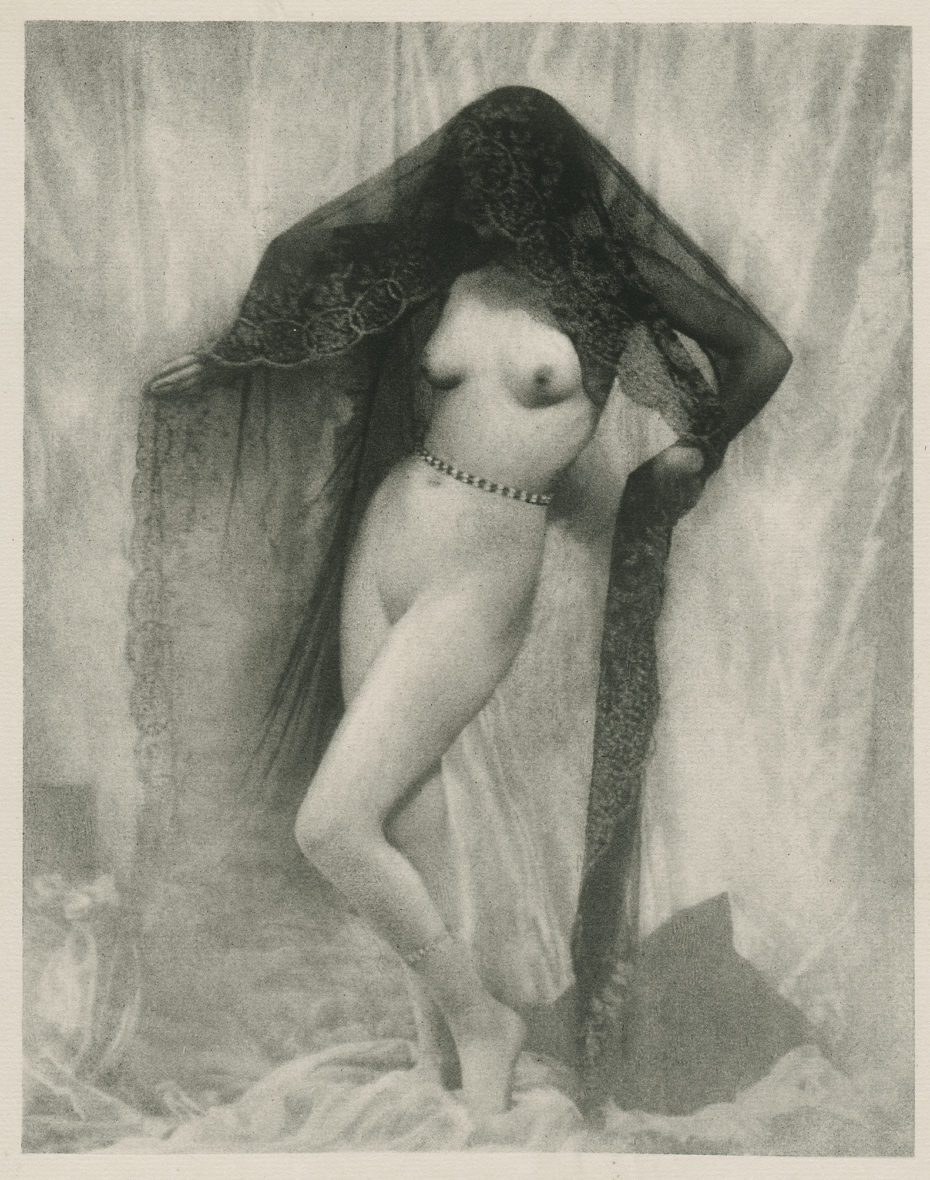

Somewhere in a dark room almost a century ago, an image emerges of a woman with her skeleton lover. Beside it, another of a gyrating goblin, a pin-up worthy witch, or some other creature from the wonderfully twisted mind of photographer William Mortensen. Today, Mortensen is praised as a pioneer of his profession, a Tim Burton type with a talent for letting the eerie and erotic mingle in his work. But for his contemporaries, he was a threat, a man whose vision made him (in the words of Ansel Adams) “the Antichrist” of Hollywood…

William Mortensen

William Mortensen

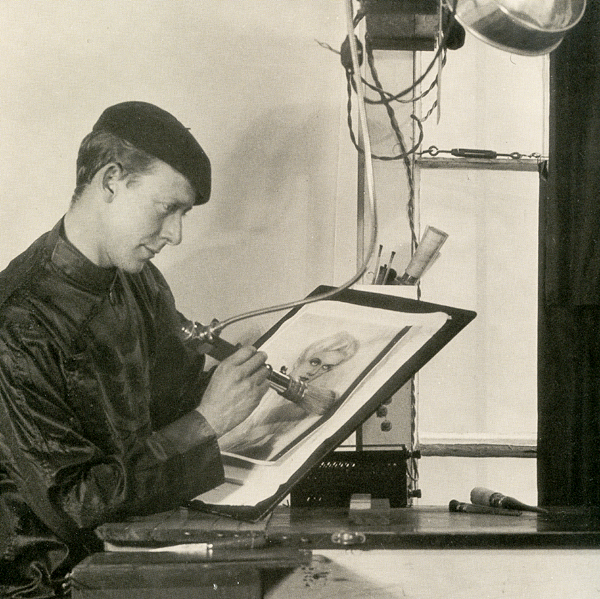

Mortensen works on an image of Jean Harlow in his studio.

Like so many of Hollywood’s golden era icons, Mortensen was originally of country stock. He left Utah for a bout in North Africa and the Mediterranean, and finally moved to Los Angeles with his fiancé Willow in 1921, accompanied by her younger sister, Fay. And this is where things already get complicated, particularly regarding how one ought to look back on Mortensen’s work…

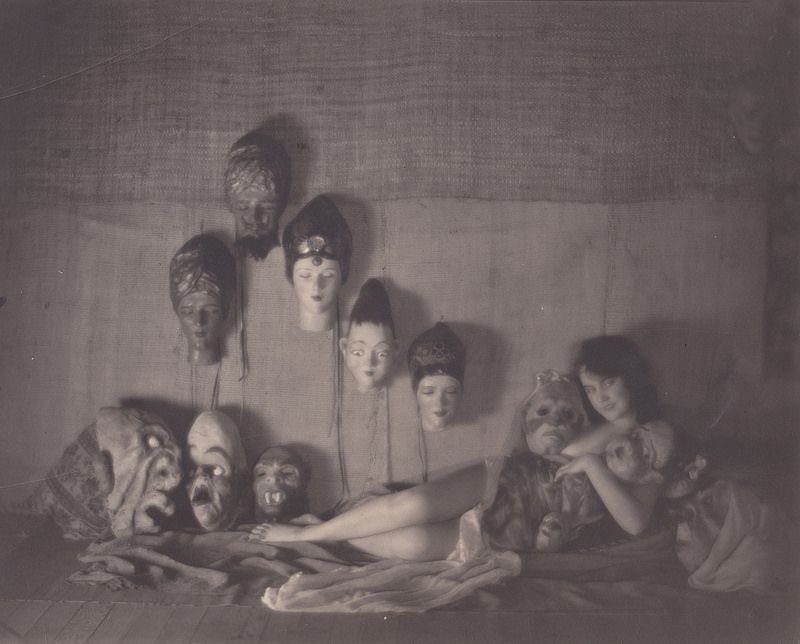

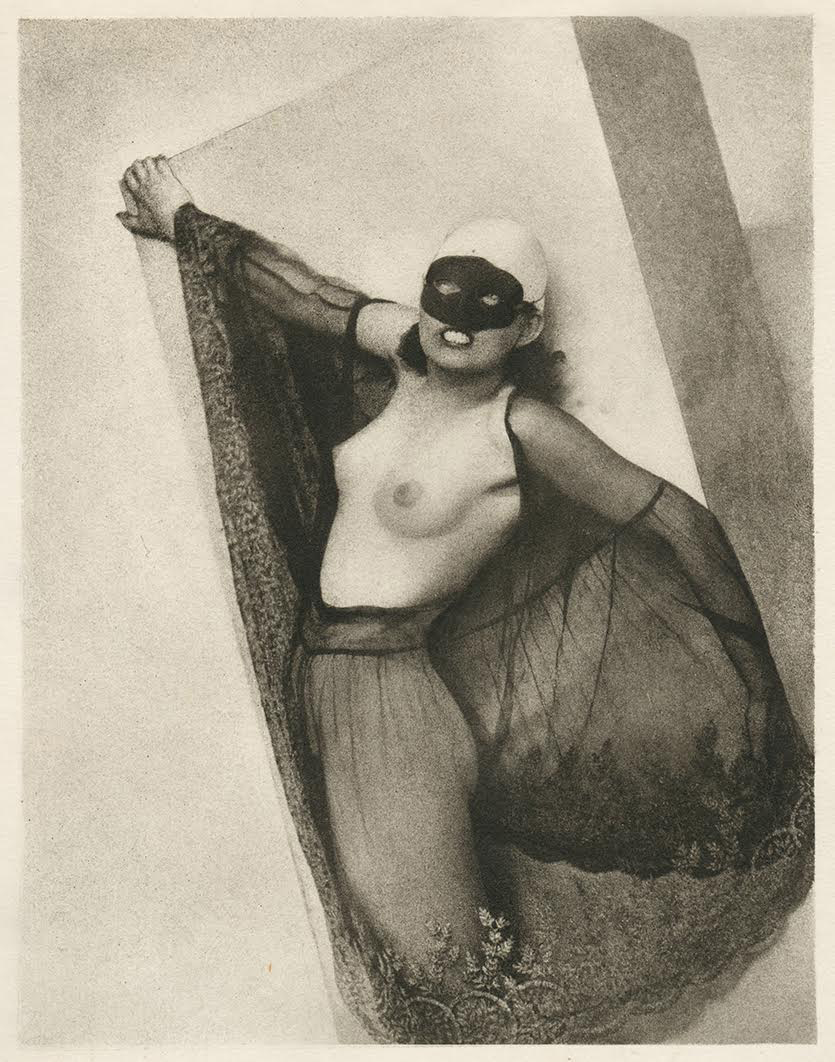

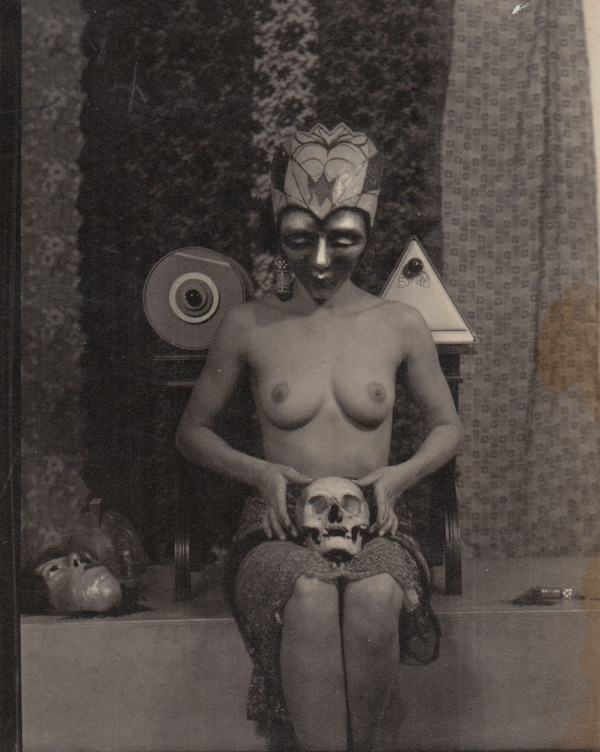

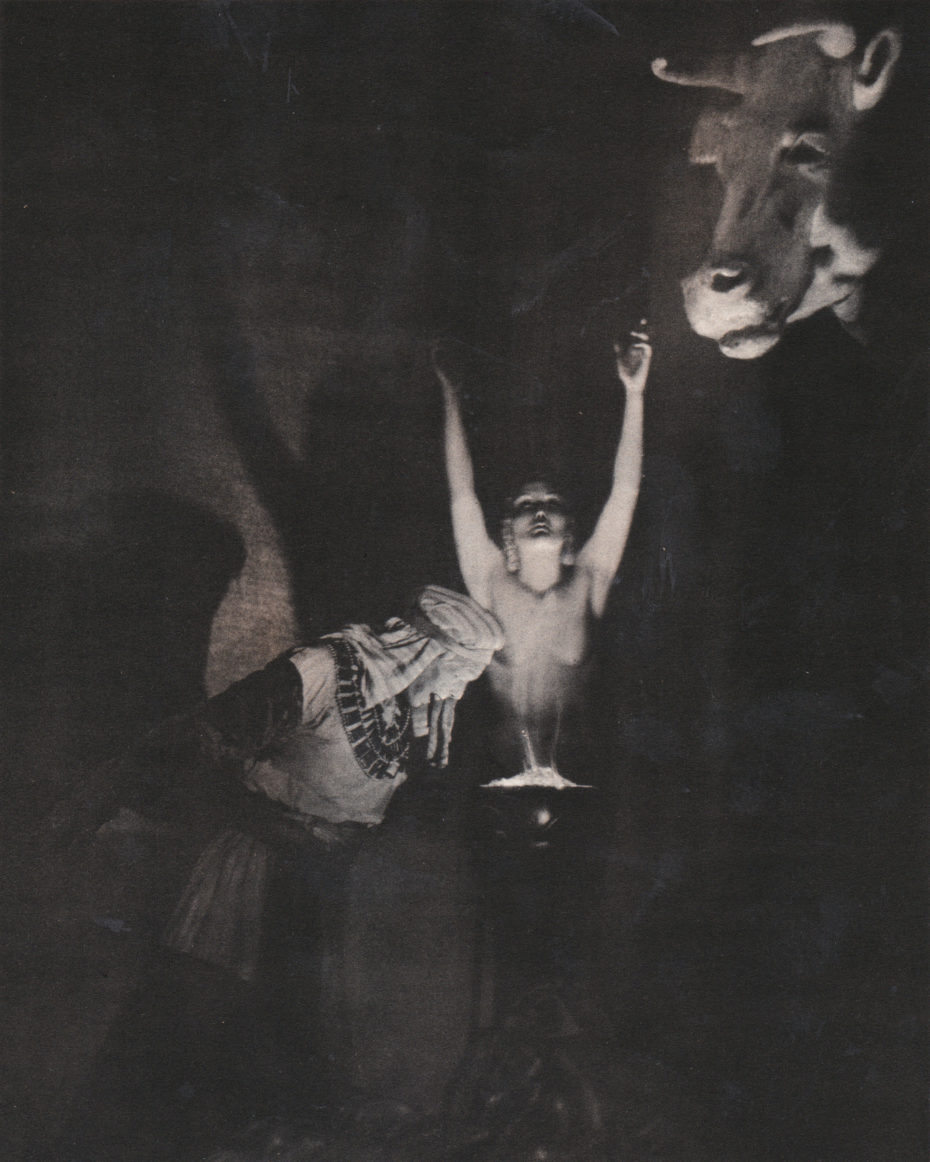

“Flight to the Sabbath” 1926, believed to be Fay Wray

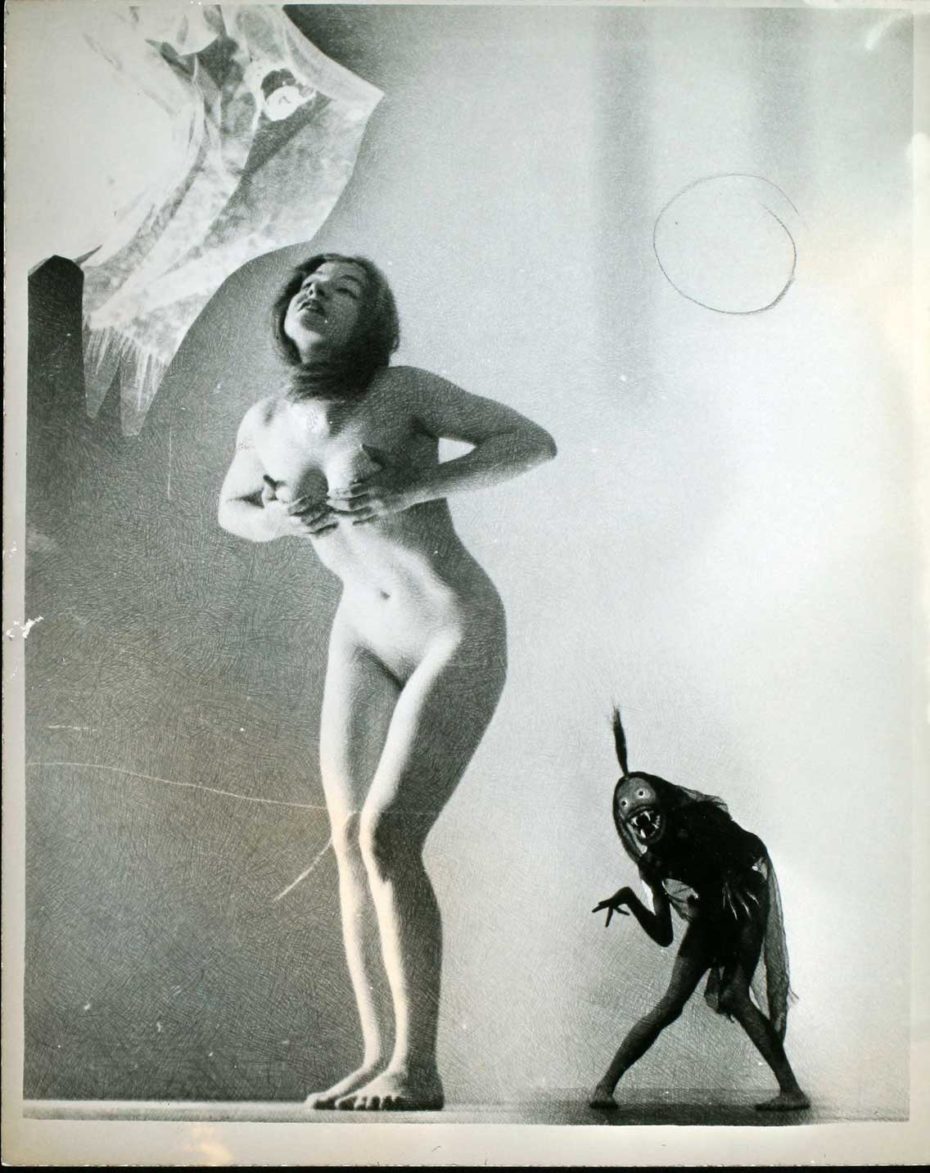

At this point in his career, Mortensen had made a name for himself taking portraits of Hollywood actors and providing film stills for the likes of Cecil B. DeMille, the founding father of American cinema himself, who gave William his first break. The idea, some historians say, was that he’d be a kind of mentor and chaperone to 14 year-old aspiring actress Fay Wray, while setting up his own photography studio in Los Angeles. But the risquée nude photos he took of Fay in the coming years were enough to make her mother high-tale it out to Hollywood and rescue her daughter from Mortensen’s advances and the tarnishing of her image.

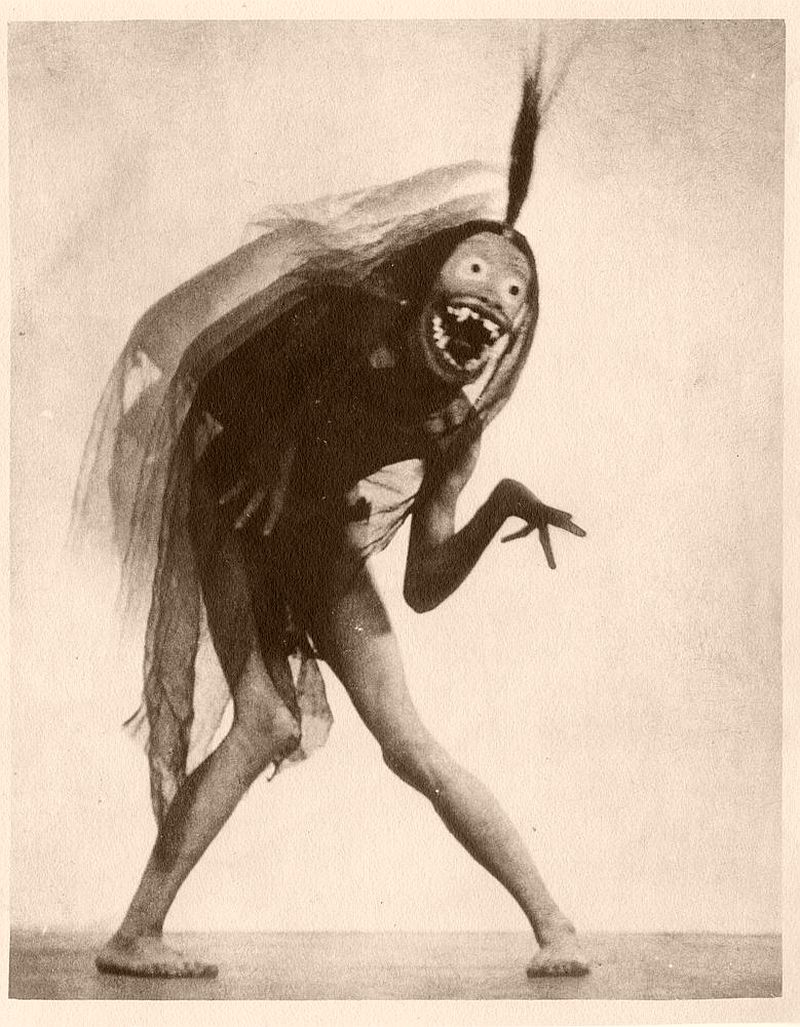

Fay Wray with Mortensen’s masks

Mortensen denied any such advances, as did Fay, but the rupture between the two parties was brutal and scandalous. Needless to say, his marriage to Fay’s sister didn’t work out, but Fay later said, “William Mortensen had never tried to embrace me. Perhaps if he had, as my mother imagined, I would have been compelled to walk out of the house and go to him. It was numbing to think that in her eyes, all the time I had been in California, I had been a very wicked person.”

William Mortensen

Fay went on to become one of Hollywood’s first real “Scream Queens” in King Kong and Mystery of the Wax Museum, the original House of Wax horror flick, while Mortensen continued on with his photography, finding a wife and muse in a woman named Courtney Crawford.

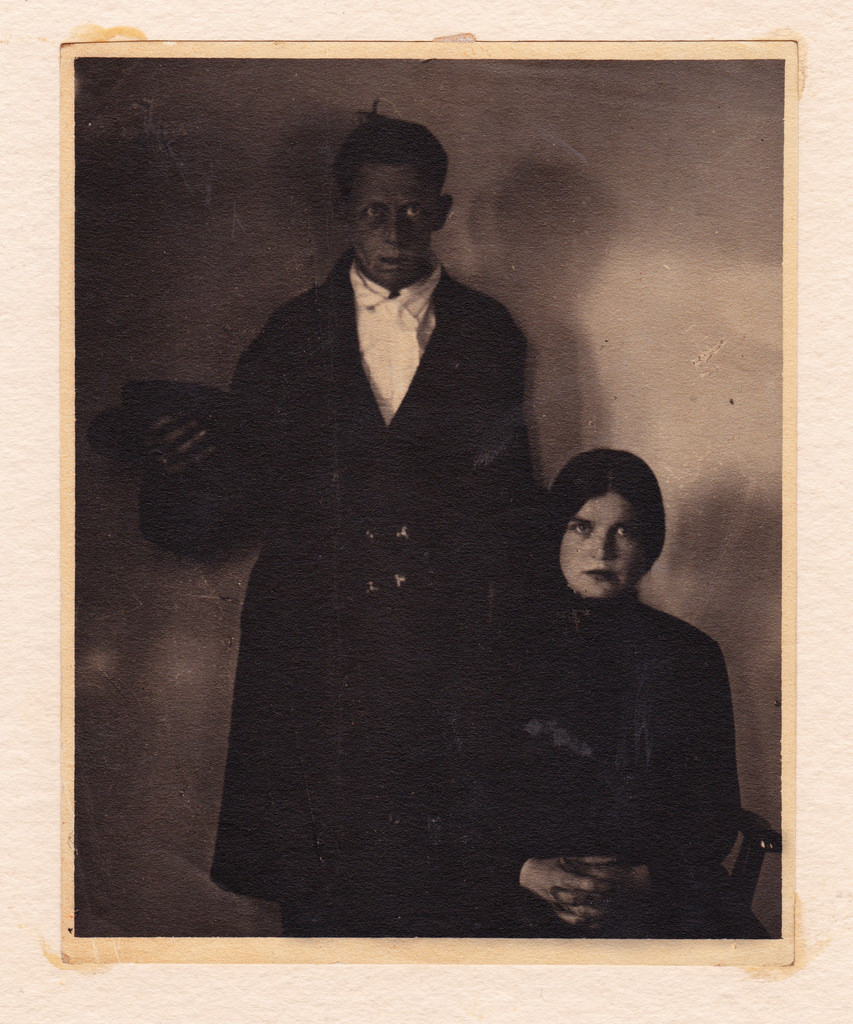

Self Portrait of William Mortensen and Courtney Crawford, 1926

Courtney Crawford

West of Zanzibar, 1928

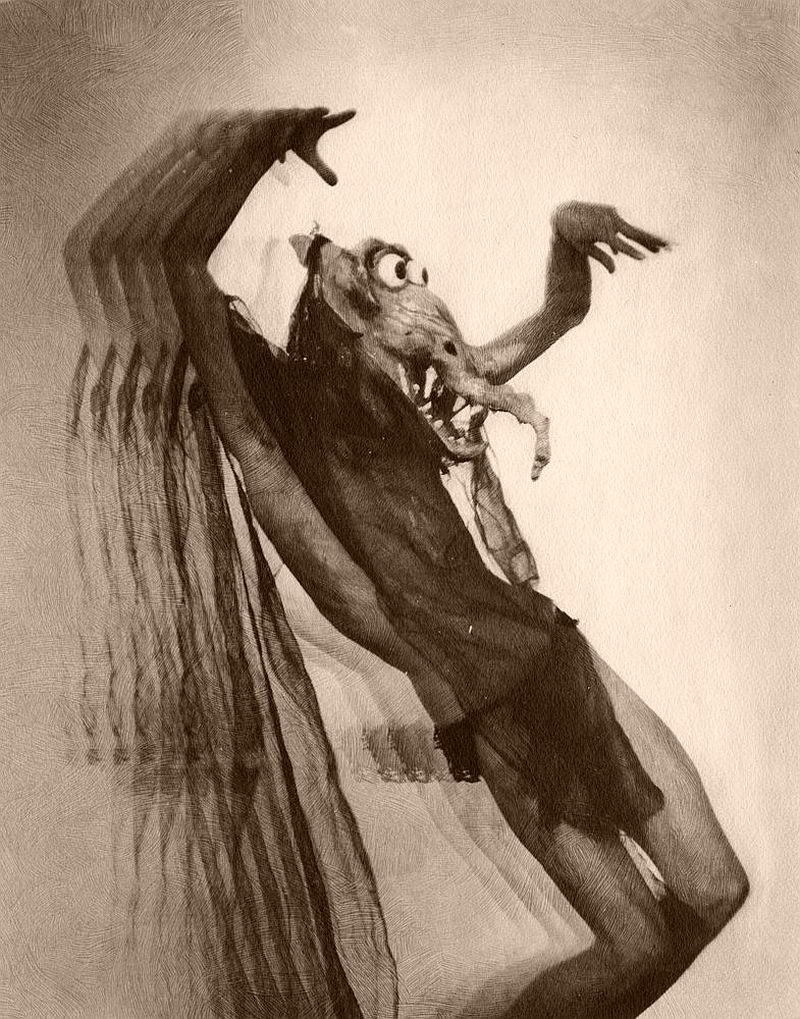

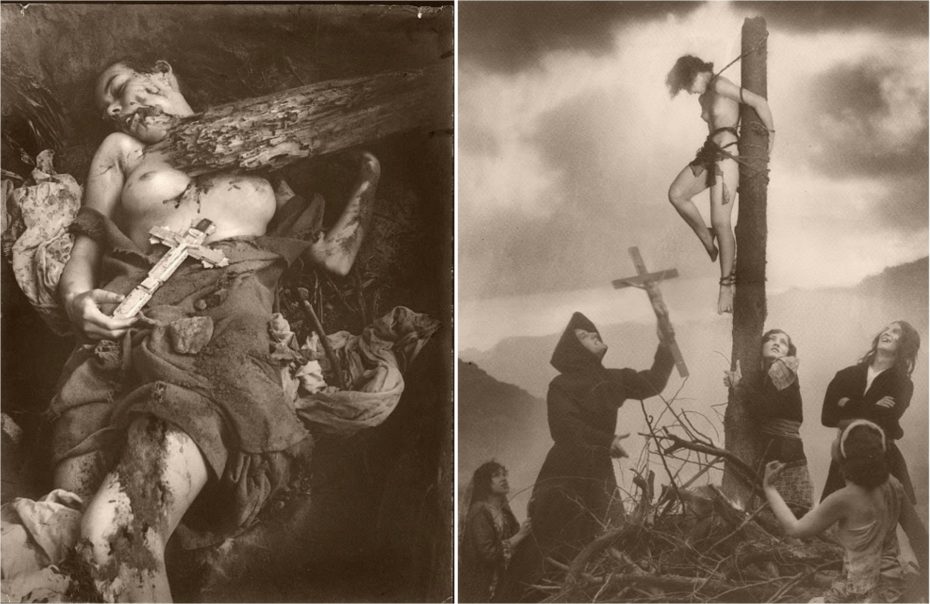

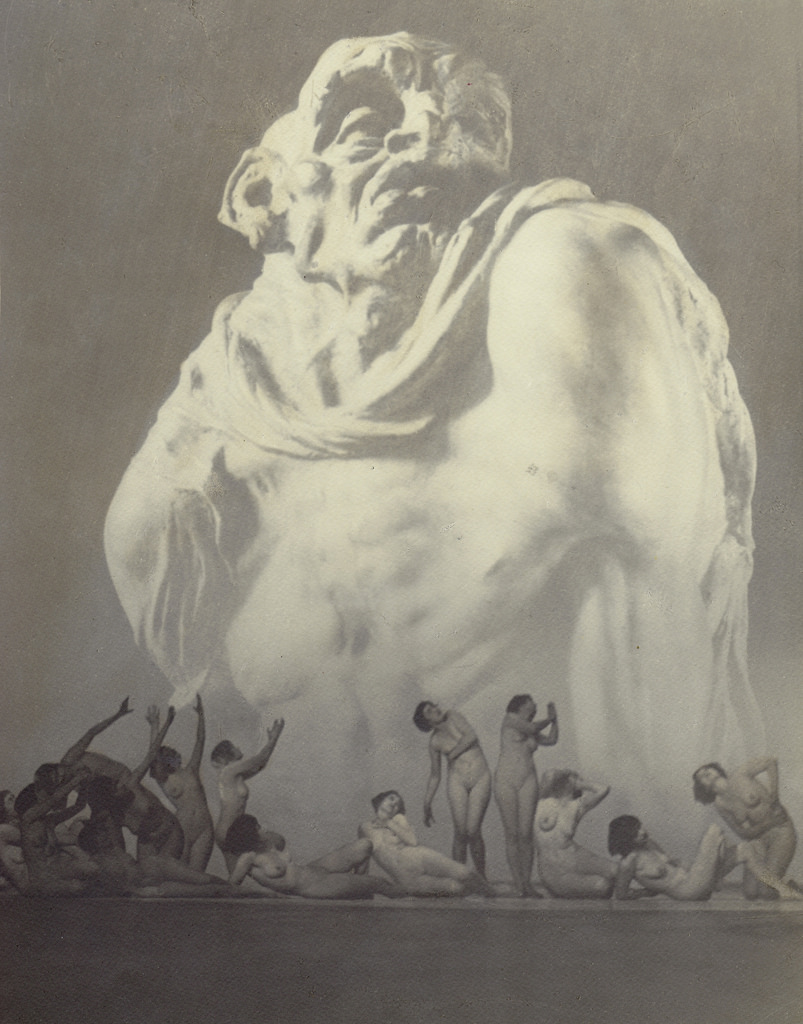

It was one thing for Mortensen to perfect his ghoulish vision on Hollywood sets like 1928’s West of Zanzibar (above) by director Tod Browning, whose film Freaks would become one of history’s greatest (and scariest) horror films– the masks he crafted were inspired by his travels, and better than anyone else’s in the business– but off-set, Mortensen’s taste for the macabre was just beginning, and the eerie manipulation of his own photographs provoked disgust, jealousy and above all confusion amongst his contemporaries.

Larry Lytel of the Laguna Beach Historical Society says, “he is amongst the most problematic figures in photography in the twentieth-century”, while also, “in a sense, photography’s first superstar”. Critics have reduced his work as “bowdlerized versions of garage calendar pin-ups and sadomasochist entertainment [with] contrived set-ups and sappy facial expressions.”

Calling it a “blind alley”, he rejected realism in photography and said that “more than just objects of aesthetic beauty to be admired, photographs should have an effect on the viewer, exploring extreme emotions and inspiring extreme reactions”. Naturally, this ruffled the feathers of those who embraced realism. American landscape photographer Ansel Adams with whom Mortesnsen had an on-going and heated correspondence, simply called him “the Devil” and “the Antichrist.” We can’t help but think that for Mortensen, it was kind of a compliment…

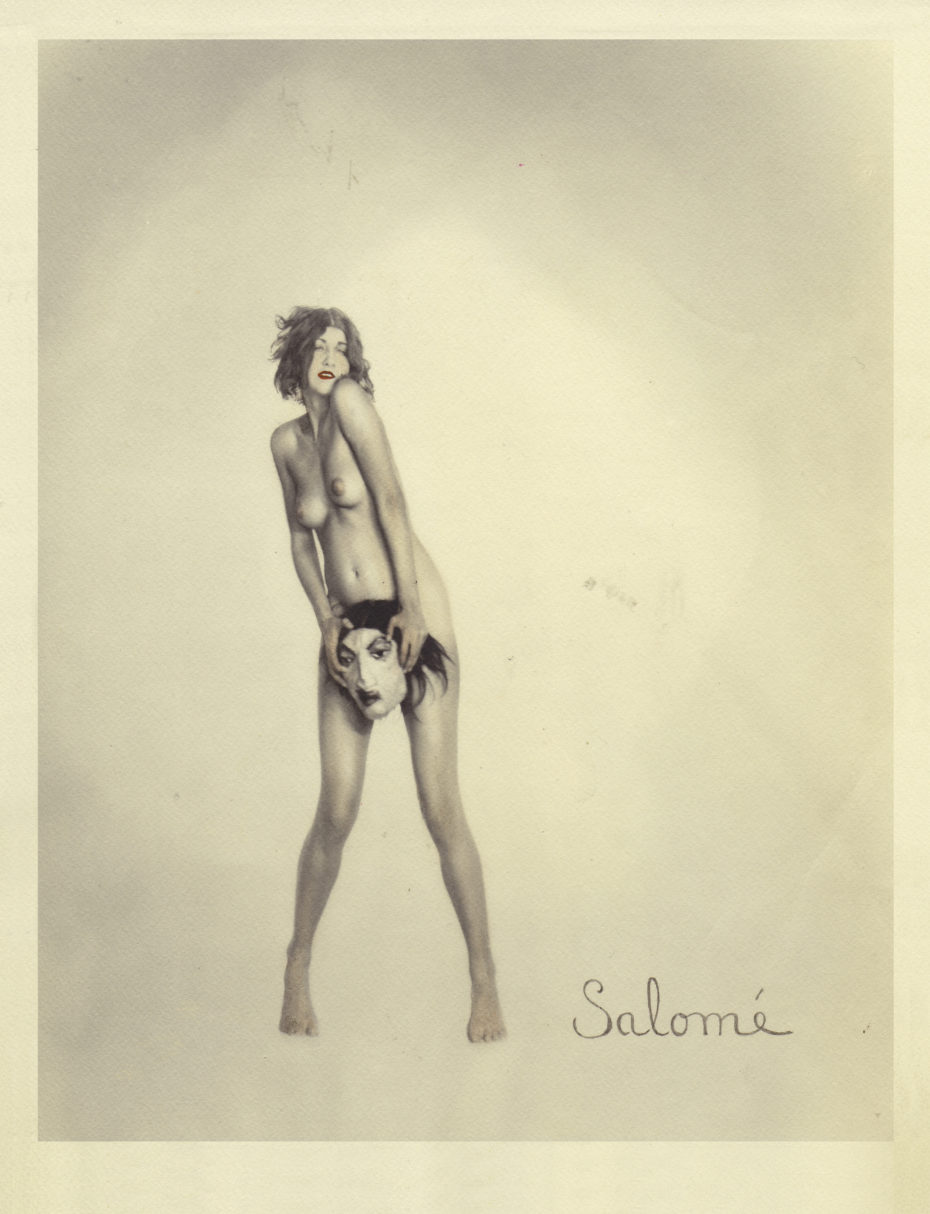

His portraits interpreted history’s darkest and most savage mythological tales, and his preferred subjects included witchcraft, torture and Satanic rituals. A Christian Scientist himself, he loved to shock with nudity, violence and death, becoming a master of macabre.

And while these photographs might be shocking to the modern eye, just imagine reactions when they were published in American magazines like Vanity Fair. He wrote best-selling books, a photography column in the Los Angeles Times and don’t forget his photography school in Laguna Beach where he taught thousands of students. This was long before the public would be exposed to such graphic content. But Mortensen believed that his work was a way for the viewer to overcome emotions such as fear and hatred. “When the world of the grotesque is known and appreciated, the real world becomes vastly more significant.”

Things were going well for him until word of the nude pictures he took of Fay surfaced, making her studio, Paramount, very unhappy. So unhappy, that they drew up a contract for Mortensen to sign declaring he had manipulated the photos to fake her likeness– not exactly the street-cred you want in Hollywood, but he probably didn’t have much of a choice. By the 1930s, he’d split for a new neck of the woods, Laguna Beach, with a new muse, Myrdith Monaghan:

From then on, Mortensen’s cackling coven of witches, goblins, and demons had calmed to a mere whimper in the public ear, particularly in the midst of WWII. The public was more interested in seeing “realistic” photography, and that shift, when combined with his mounting ostracisation in the photography community, saw him fall into obscurity until his death in 1965. Only in recent years has his work started resurfacing in all its glory…

Research and image sourced in part from AMERICAN GROTESQUE: The Life and Art of William Mortensen (edited by Larry Lytle & Michael Moynihan; Essays by Larry Lytle, William Mortensen & A.D. Coleman).