Finding it there seems improbable. Absurd, even. Yet, on a sunny day in Sector G of the Bronx, amidst cheap Thai massage parlours and “99¢ Only” stores, stands the final home of the king of American macabre, Edgar Allan Poe. That the house stands after 221 years is a miracle alone. It’s been a quiet witness to revolution, urban sprawl, abandon, and, above all, Poe’s greatest heartbreak. “Historians say,’Oh, he wrote some of his best work here’, and that’s true,” says Vivian Davis of the Bronx Historical Society, who gave MessyNessyChic special access to the cottage’s treasures, “But a lot of people don’t know the ‘love story’ side.” She’s talking about Virginia Clemm, Poe’s ill-fated wife who died in the back bedroom in 1847, in a story as darkly tragic as one would expect from him…

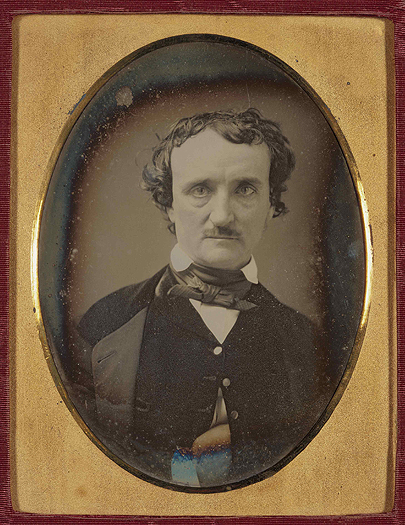

A daguerreotype of Poe taken shortly before his death.

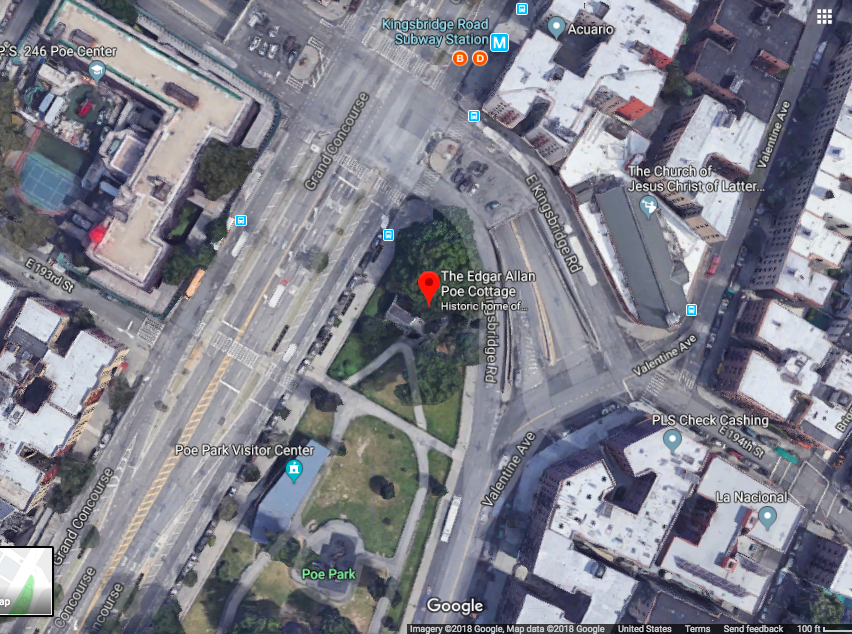

Okay, but still trying to wrap your head around the image of Edgar Allan Poe in the Bronx? An aerial shot of the house beside towering apartments really puts it in perspective.

“Needless to say, this area of Fordham was totally different back then,” says Davis, “When Poe moved here in 1846 it was to try and heal his wife, Virginia, who had a disease called Consumption, because, well, it consumed all of you.” Today, we call it Tuberculosis.

The author of classics like The Tell-Tale Heart and “The Raven,” Poe had gained considerable success and celebrity at this point in his career, but never any real money. By the time he moved to the Fordham area of what’s now the Bronx, he’d been hopping around various New York living situations (18 times, to be exact), and pinching pennies to provide Virginia with the life he felt she deserved, but he couldn’t afford. The house in the Bronx was his last hope, especially at $5 a month rent.

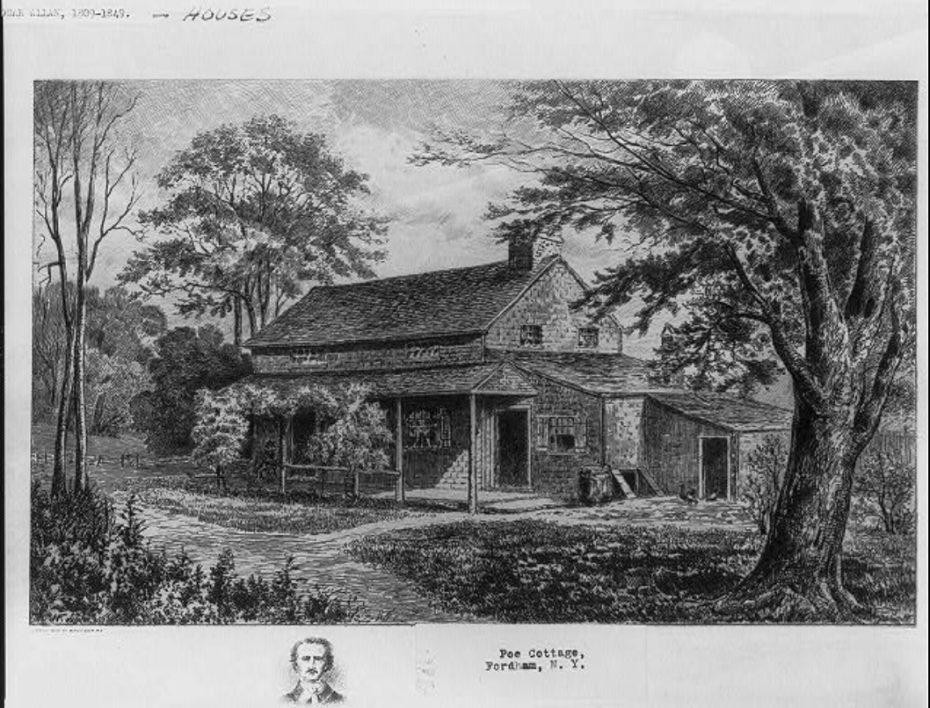

The cottage circa 1910, before it was moved to Poe Park a few blocks down (image: The Library of Congress).

He moved in with her and his mother-in-law, albeit it vain. Virginia’s troubles began years earlier, on a night of piano playing that Poe later describes in horror, wherein she opened her mouth to sing but instead spat out blood. “Her life was despaired of,” he wrote years later, “She recovered partially, and I again hoped. At the end of a year, the vessel broke again. I went through precisely the same scene. . . . Then again — again […] Each time I felt all the agonies of her death — and at each accession of the disorder I loved her more dearly and clung to her life with more desperate pertinacity. I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”

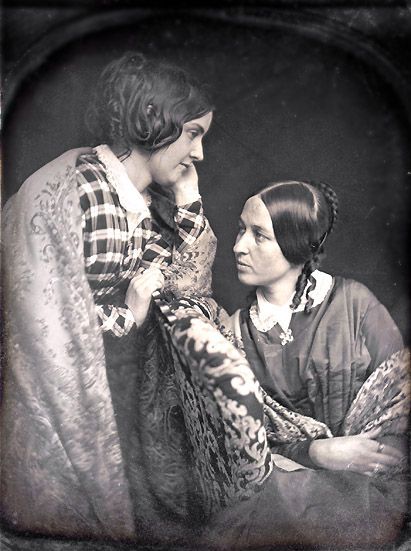

A possible photo of Virginia Poe (left).

It was hell on earth for the already neurotic Poe, who “loved Virginia very deeply, but also had this very mysterious relationship with her family,” says Davis, who explains that he married Virginia when she was only 13 and he, 27, and that she was his cousin. (And yes, it was weird even “back then”.) Some historians see their relationship in a more platonic scope, while others think he may have had some kind of professional arrangement with her mother, who also lived in the cottage even after their deaths. “But what is very clear in his writing,” says Davis, “is that Virginia became his world.”

“The cottage had an air of taste and gentility… So neat, so poor, so unfurnished, and yet so charming a dwelling I never saw,” wrote one visitor to Poe’s house. Today, the house is filled with authentic period furnishings in the same minimalist style, and three items that actually belonged to the Poes themselves: a rickety bed, a rocking chair, and a golden mirror. Sound like the intro to one of his own stories? Good.

Virginia fell more and more ill, and rumours stirred about the city — were both of them dying? Would the literary community really let Poe live on the brink of poverty as he carried the weight of the family, financially and, in Virginia’s case, literally?

“This is the bedroom Virginia was moved to when she couldn’t walk,” says Davis, who lets us in to see the first of the three Poe relics: Virginia’s deathbed. To the left are the narrow stairs that her “Eddy”, who wasn’t exactly brawny, carried her up and down in his arms.

Oh, and you know that saying, “Sleep tight, don’t let the bed bugs bite”? Well the former part of the rhyme, says Davis, references the fact that folks literally tightened ropes underneath their mattresses to sleep. She lifts off the covers of Virginia’s bed to show us (and yes, we half expected a ghost to fly out).

Virginia’s death sent Poe into a deeper spiral of depression, anxiety and drinking. In spite of it all, he kept writing — didn’t have a choice, really — but “he did not seem to care, after she was gone,” wrote one of his friends, “whether he lived an hour, a day, a week or a year.” You can feel it in the words of his 1849 memorial poem for her, “Annabel Lee,” in lines like “I was a child and she was a child/But we loved with a love that was more than love/That the wind came out of the cloud by night/ Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.”

He visited her grave constantly, and “Many times was he found at the dead hour of a winter night, sitting beside her tomb almost frozen in the snow,” wrote his friend Charles Chauncey Burr. Then, in 1849, Poe was found delirious and ragged in the streets of Baltimore, dying shortly afterwards in one of literature’s greatest mysteries. “Poe’s death seems ripped directly from the pages of one of his own works,” wrote Smithsonian’s Natasha Gelling in a 2014 article on the author, “He had spent years crafting a careful image of a man inspired by adventure and fascinated with enigmas—a poet, a detective, an author, a world traveler…”

That Poe and his wife should meet such an untimely death was almost serendipitously tragic. If only he hadn’t left the cottage for a press tour, he might’ve skirted death; instead his mother-in-law, now without a daughter and a son-in-law, lived out another twenty years in the house, alone, likely selling off the family valuables piece by piece to eat.

In spite of it all, the chair still rocks, with the gold mirror glowing behind it…

Really though, that mirror. It gives off an energy all its own with its time-stained, cracked glass. When asked if anything funny has ever happened around it (or the bed), for that matter? “Well I can say some people would say yes,” she says diplomatically, and shows an unsettling video of what looks like a face appearing in the mirror. “His mother-in-law clearly held onto this mirror for a reason,” she says, “it probably meant something very special.”

But if the cottage is haunted by the Poes, we’re apt to think it’s happily so. When Poe wrote of the cottage as inspiration for his final story, the uncharacteristically serene “Landor’s Cottage,” it was with joy; when Virginia described her dream house before dying, it still seems not much has changed. “Give me a cottage for my home,” she wrote, “And a rich old cypress vine, Removed from the world […] Love alone shall guide us when we are there.”

You can also step inside Poe’s house, which is open Thur & Fri 10AM-3PM, Sat 10AM-4PM, Sun 1-5PM Admission ($5/adult, $3 for students & seniors). Learn more about visiting on the Bronx Historical Society’s website.

Special thanks to the New York Historic House Trust, The Bronx County Historical Society, and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.