The cultural shift between pre and post-WWII world Japan was complicated and often divisive, but if you were photographer Eikoh Hosoe, that tension became fuel for creative expression that turned into a surrealist dreamworld – or nightmare, depending on who you asked. The Japanese artist’s works mirrored the state of a shell-shocked country in the midst of Westernisation as early as the 1950s (which we’ve already talked about in detail here), as he created images that dealt with the intersection of identity, illusion, and tradition in his homeland.

It was Alice in Wonderland meets the Atom Bomb; the Nuclear Family colliding with the need for a brutal expression of individuality, and a steadfast love for old Japan. Like so many artists, his work can often be broken down by his muses, so we’ll start with one of the most famous: Yukio Mishima…

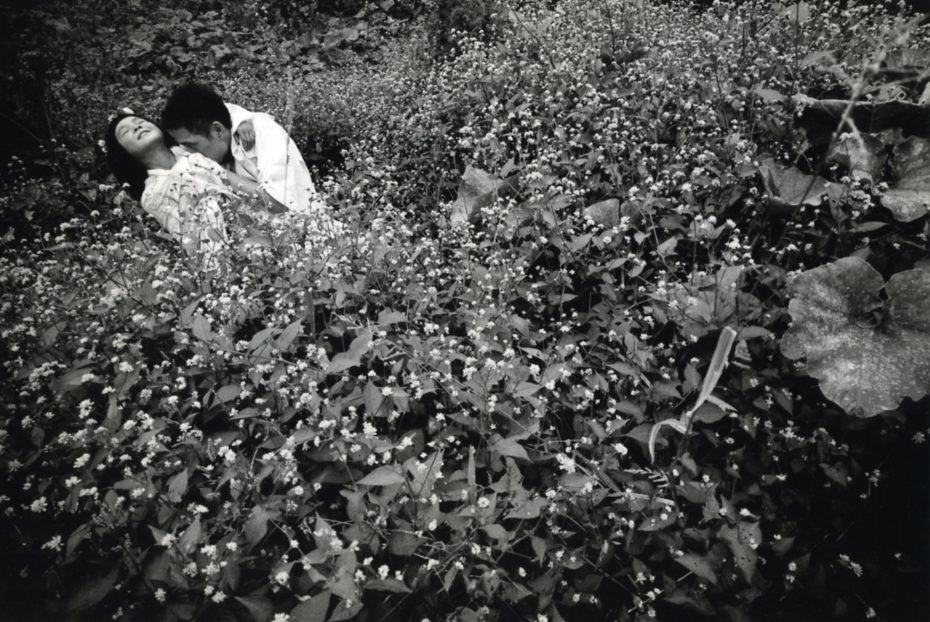

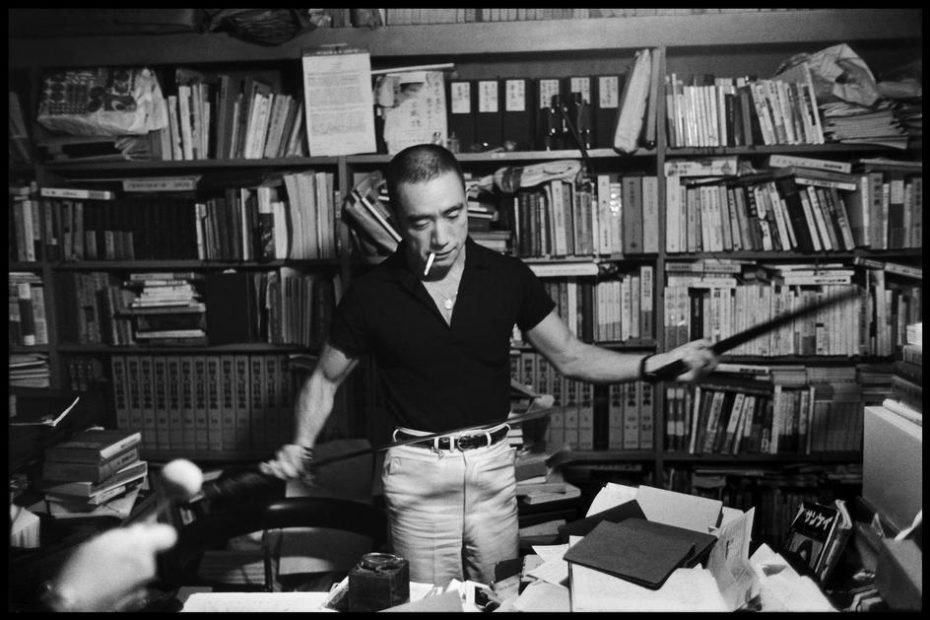

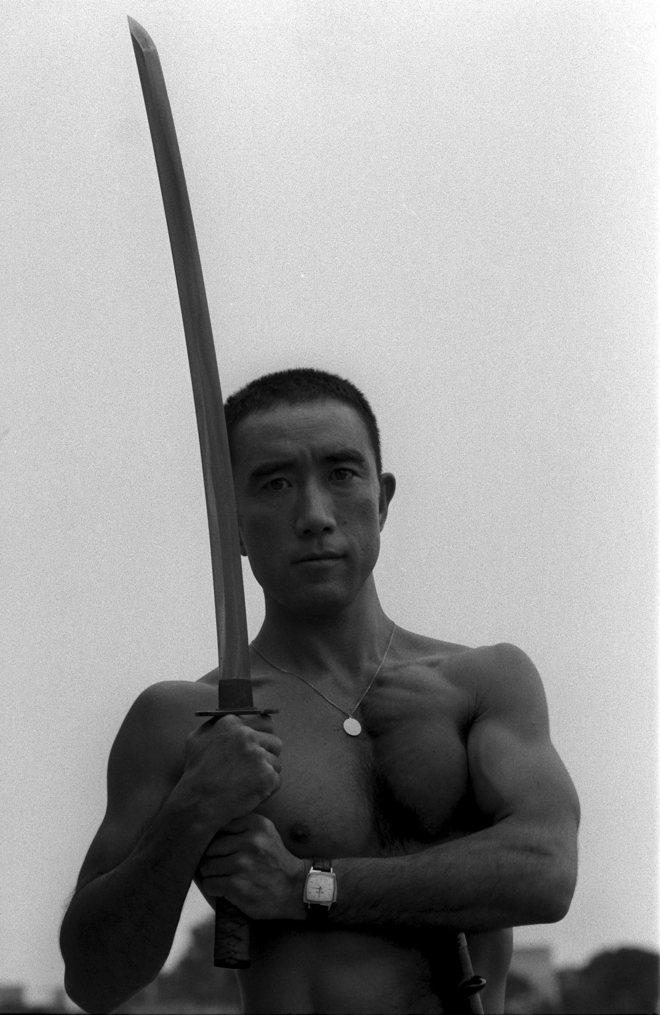

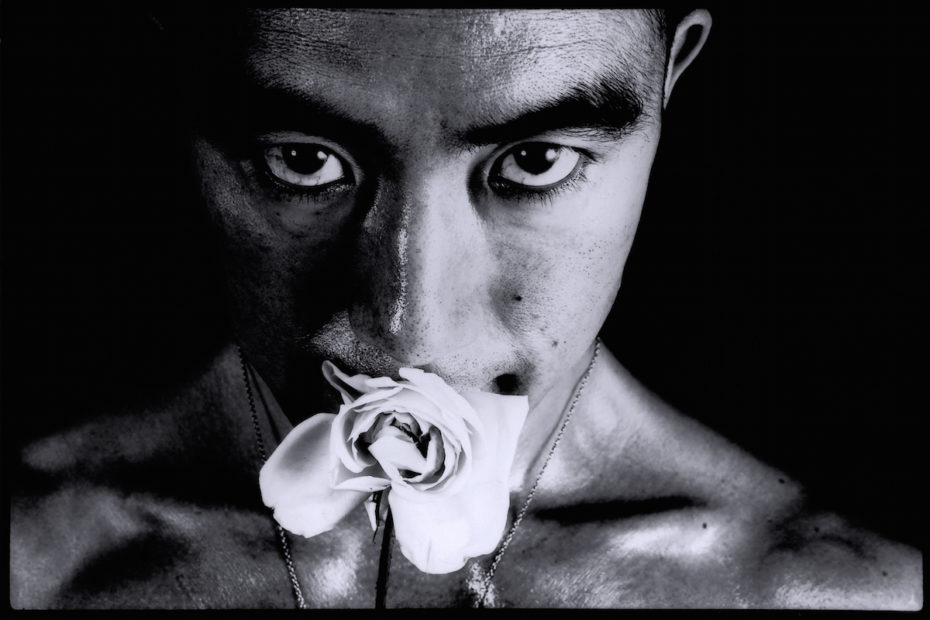

One of Japan’s most controversial figures, Mishima was an actor, author, poet, and playwright, but always in the service of a Nationalist ideology. He was the perfect medium for Hosoe to explore the clash between new and old Japan, because as much as he was a symbol of the traditional, Mishima was also revered in underground circles as a homosexual writer — think a fascist foil to Oscar Wilde. And with a Samurai sword.

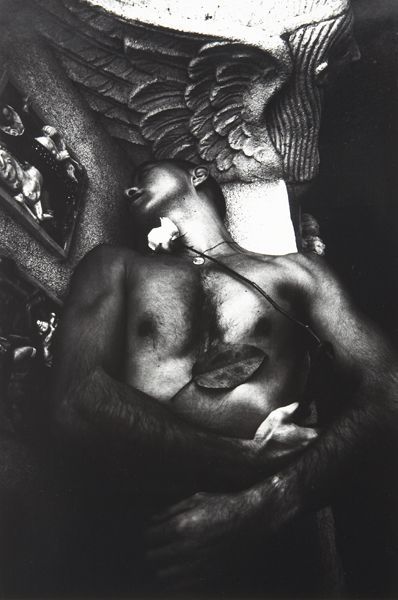

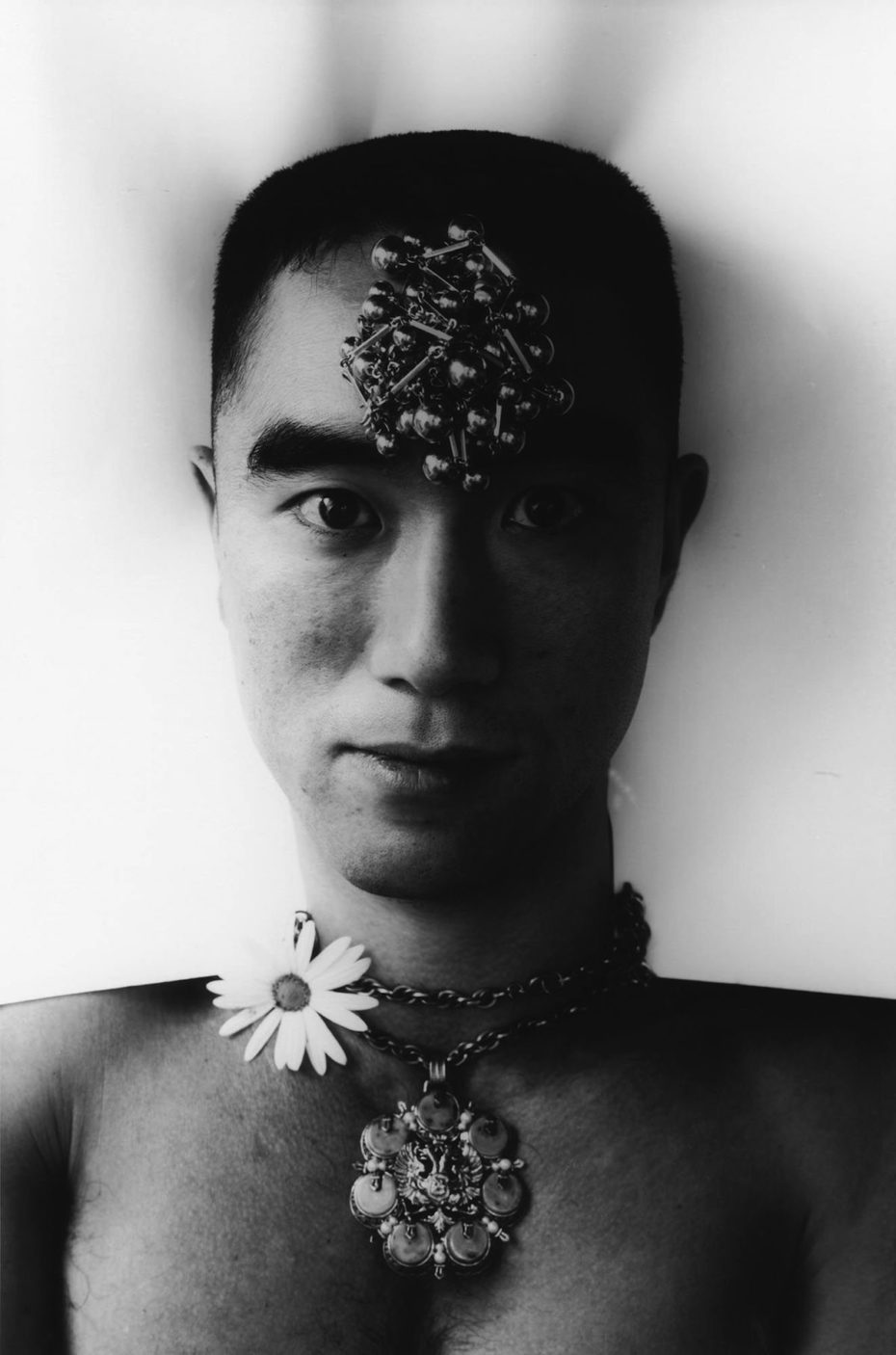

Mishima had even founded the Tatenokai (Shield Society), a group “dedicated to upholding values of traditional Japanese culture,” that almost seized control of the government’s Self Defence Force in the early 1970s. The coup d’état ended brutally, with Mishima committing seppuku (suicide by Samurai sword) on the steps of a government building, in front of his 100 or so followers as a final act of defiance. In light of of his death, the photographs of Mishima were coloured with a much darker — and foreboding — energy. Hosoe called the series, Ordeal by Roses:

They might not seem shocking today, but remember these photographs were taken during the same era when this was the incoming, main-stream aesthetic:

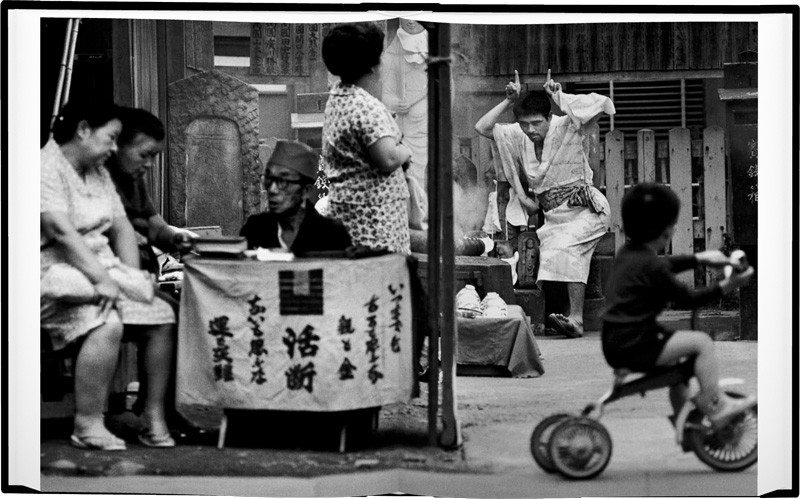

Hosoe’s fascination with identity in post-war Japan started in his teens, when he was in his school’s English language club and photography society. His cousin advised him to change his name (then, Toshihiro ) to something “more suited to the new era.” Thus, Eikoh was born, and he went armed with a camera into neighbourhoods where U.S. military housing was established. The images he captured were often unsettling because the times were unsettling, and today critics see Hosoe’s life work as both a reality check, and a kind of psychological escape.

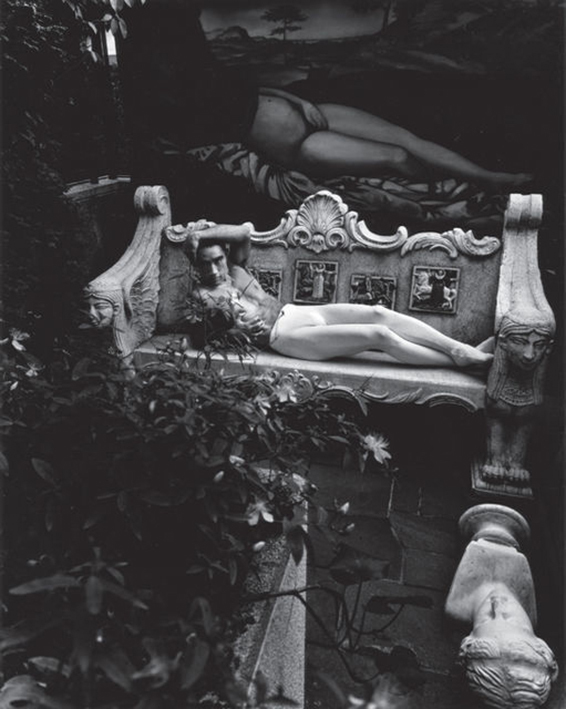

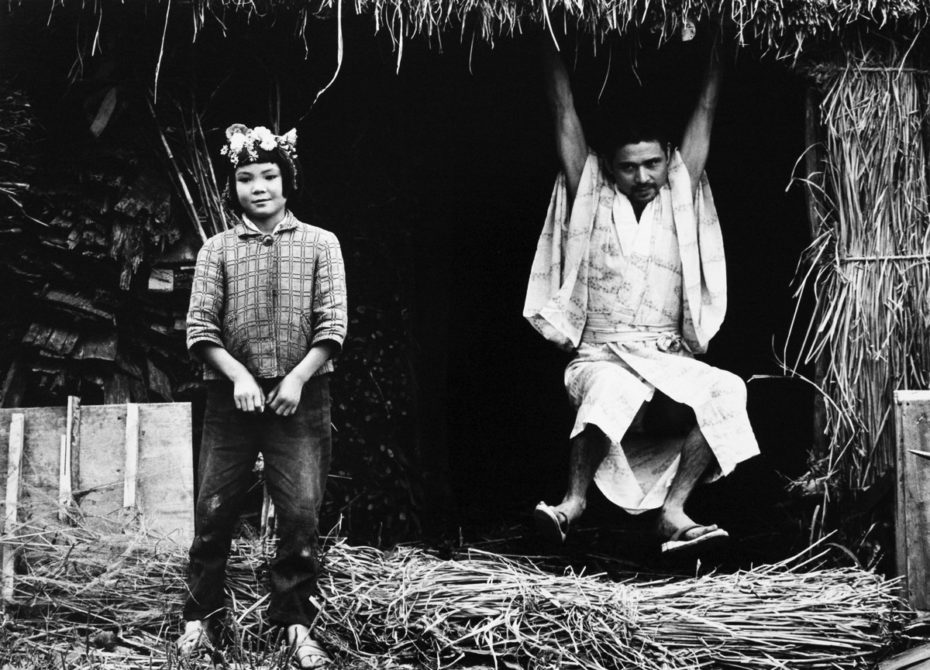

And in matters of escapism, Hosoe became king. One of his most beloved series was a collaboration with another muse, the dancer Tatsumi Hikikata. In 1969, they traveled to a small village in the North of Japan, snapping pictures of Hijikata’s spontaneous dancing with locals, and prancing around while dressed up as a weasel-demon from Japanese folklore, kamaitachi (the title of the series)…

For New York Times critic Margarett Loke, Hosoe was on the brink between Surrealism, and the contemporary equivalent of becoming a full-blow Goth. Yet, his attraction to the dark and phantasmagoric wasn’t really a rejection of life and joy — nor a defeatist attitude towards the future. “When you take a photo at 1/1000 of a second, the moment can become an eternal fact,” Hosoe explained, “an eternal moment.” They were born of destruction, but preserved a collective memory.

After the 1970s, Hosoe went on to found the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, where he has been Director since 1995. The museum collects modern and contemporary platinum prints from both Japan and overseas, and operates under the mission statement, “Embrace photographic art made in the affirmation of life.“