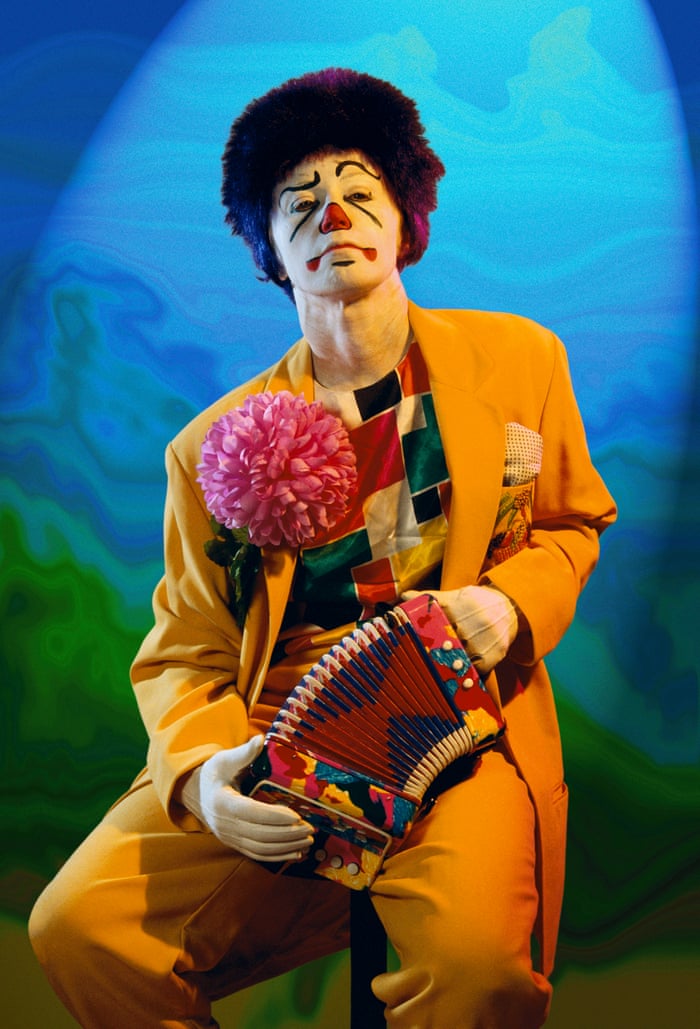

She’s the woman of a 146 faces (our ballpark guess), as well as the stylist, makeup artist, art director, model, and, above all, photographer behind their creation. For today’s art students, Cindy Sherman is a postmodern prophet of the über meta in photography, a woman who toyed with the concept of selfies and identity long before Instagram, memes, and the edgy grad school lectures that followed. Her characters are all insanely different, but feel like some misfit army from another dimension, banding together to open a dialogue on what it means to be a 1950s housewife, a film noir heroine, a medieval courtesan, a clown, and almost always, a woman.

Yup, they’re all Sherman. Some see the artist’s work as disturbing flings with stereotypes, but for others, she’s become the art world’s Joan of Arc. “She shows us fashion as costume, compulsion, camp, ritual, and necessity,” says art critic Jerry Saltz in a 2012 article for NY Mag, “Sherman delights in the mortification of the self, revelling in it like an epicurean at dinner.”

Photograph by Martin Schoeller / Saba

For Saltz, she’s nothing short of a “warrior artist, one who has won her battles so decisively that I can’t imagine anyone ever again embarking on a lifetime of self-portraiture without coming up against her.” In case you’re wondering, the above portrait is what Sherman normally looks like.

But for someone who spends hours in solitude dressing up like a dejected clown, Sherman had a pretty vanilla upbringing. She was raised as one of five kids in New Jersey to an engineer father, and a mother who taught reading skills to children with learning disabilities.

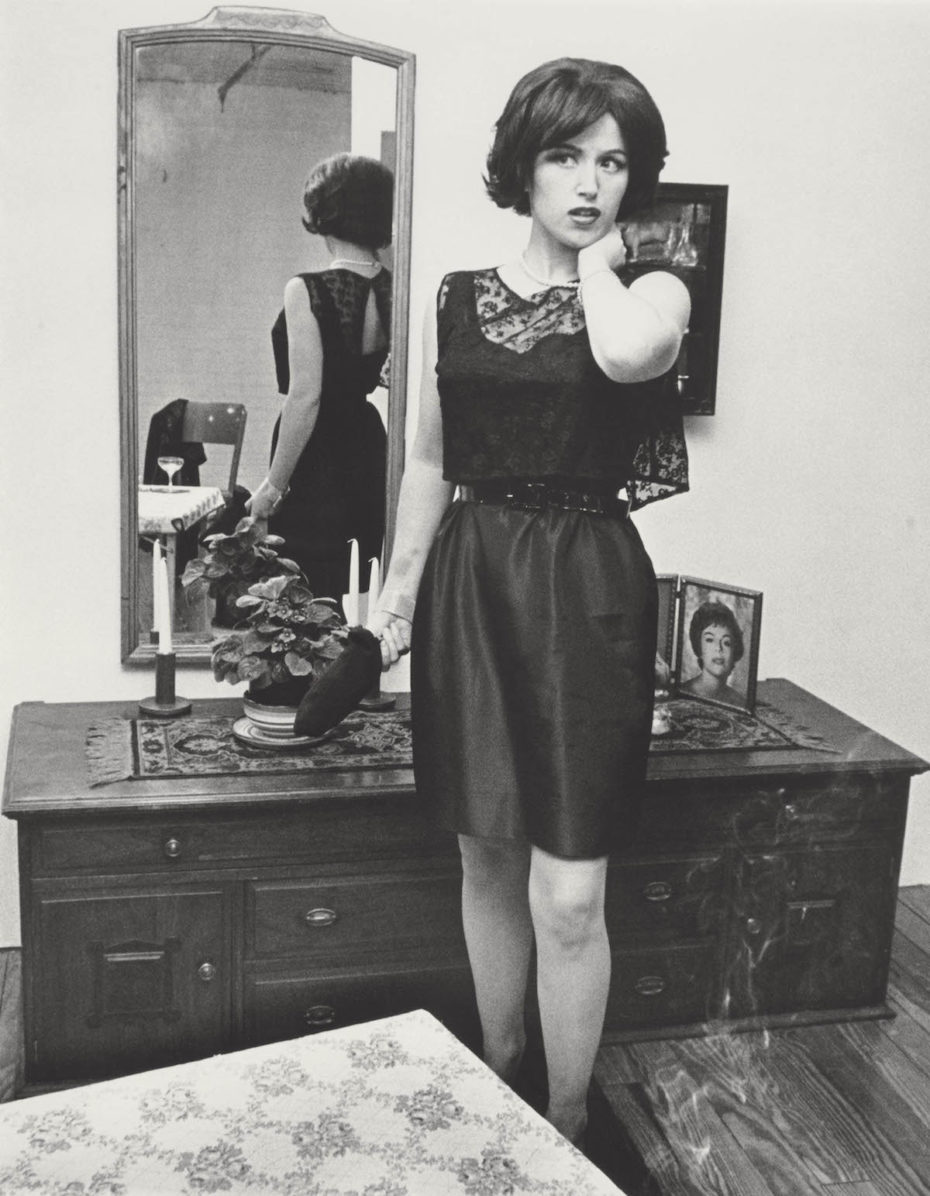

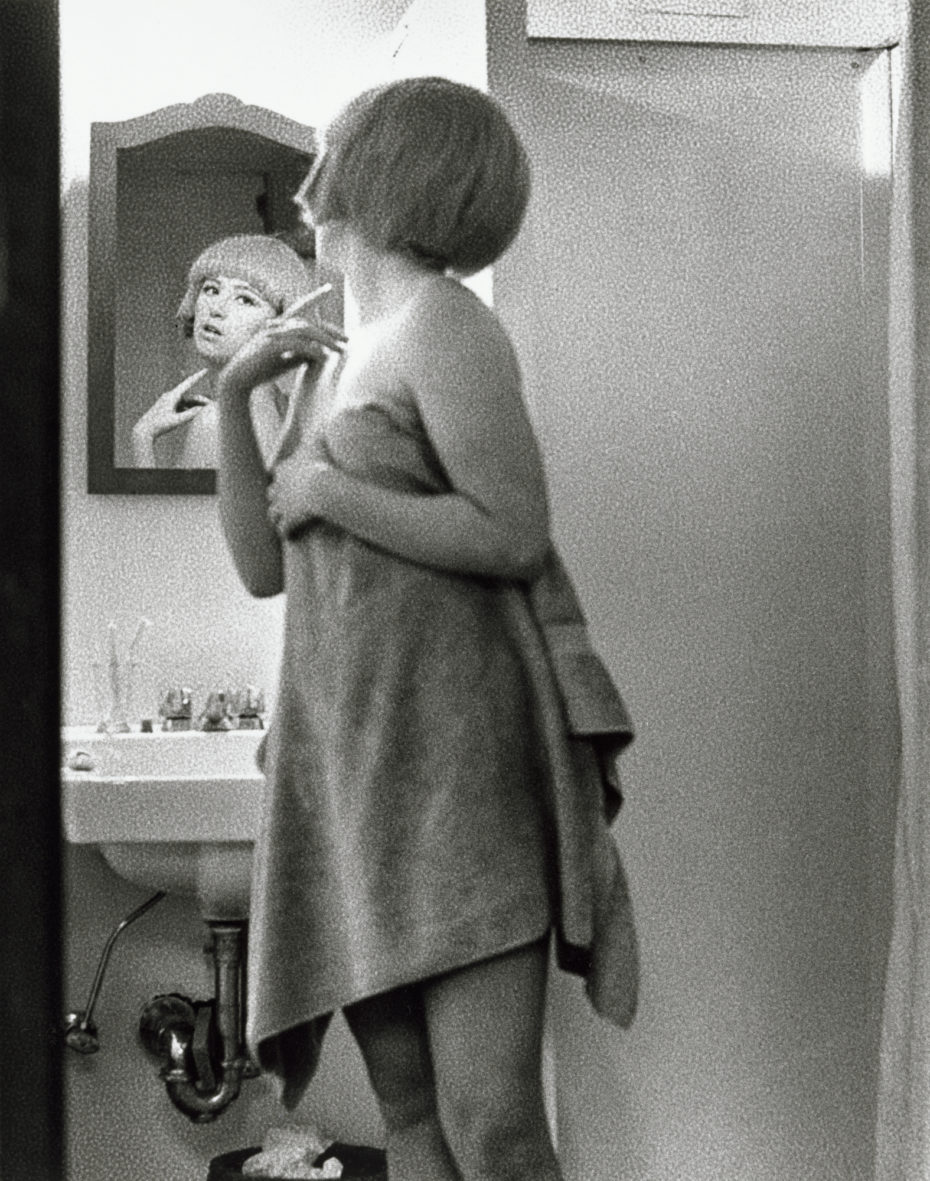

When she started school in the 1970s at the State University of New York, at Buffalo, it was to study painting. But Sherman soon found “[t]here was nothing more to say [through painting]. I was meticulously copying other art, and then I realized I could just use a camera and put my time into an idea instead.” Her breakthrough Untitled Film Stills, (1977–80) are a great example of early Sherman, honing her craft as B-movie and film noir actresses in over 70 photos:

She wanted the viewer to imagine her as a heroine in-between important scenes, outside of action and narrative, and open to their own interpretation. The imagery was powerful, and evocative of what felt like a film you’d seen a hundred times before.

Only, you didn’t, and that’s the magic of Sherman: she made the viewer do half the work by projecting their own assumptions, clichés, and fears onto her work. She not only carved out a place for pop culture and the ‘low-brow’ in the haughty art world, but she made it interactive.

“People are often amazed that someone as ‘nice’ as Cindy Sherman could be a major artist,” wrote The New Yorker’s Calvin Tomkins almost two decades ago, “By nice, I mean friendly; modest, warm, considerate, and even-tempered—qualities that we do not usually associate with artistic ego, and which might seem antithetical to the disturbing and phenomenally influential work that this artist has produced.” She’s had her work shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and just about every biennale and fair on the circuit, had a major retrospective at MoMA, worked with designers like Prada and Comme Des Garçons.

But does Sherman find any traces of herself in her characters? “I feel I’m anonymous in my work,” she told The New York Times in 1990, “When I look at the pictures, I never see myself; they aren’t self-portraits. Sometimes I disappear.” For a hot second in the 2000s, she actually did disappear from the art circuit, but came back in 2016 with a series called “The Imitation of Life,” where she imitated Old Hollywood stars like Gloria Swanson.

It was a way, she explained, to digest her own experiences of getting older — especially as an artist whose face is her canvas. Sherman is now 64, and while she’s hinted at possible forays into acting on the big screen, there’s no telling what this human Rube Goldberg machine is plotting in her top secret studio.

For the time being, we’ll just have to stalk her recent Instagram account. Which is just as nuts as you hoped.