It’s time for a little breather, don’t you think? So today, we’re popping over to Beatrix Potter’s old village, in the calm of England’s Lake District. We’ll stop by Buckle Yeat for a cup of tea, and stroll through the garden where so many of her children’s book characters — namely, Peter Rabbit — got up to mischief. Whether or not you grew up with Peter, Jemima Puddle-Duck and Mrs. Tiggy Winkle, the charm of Ms. Potter’s 17th century cottage is worth the trek to the rolling hills of Cumbria. When she died, Potter left her land (as in, thousands of square acres) to the National Trust. It’s largely thanks to her that the countryside remains unspoilt, in the kind of quiet where you can hear a pin drop. Of course, there are a few more tourists there nowadays than 113 years ago. But its windy roads still make it feel like a pilgrimage into the past. Just look for the particular “wildlife” signs to make sure you’re on track…

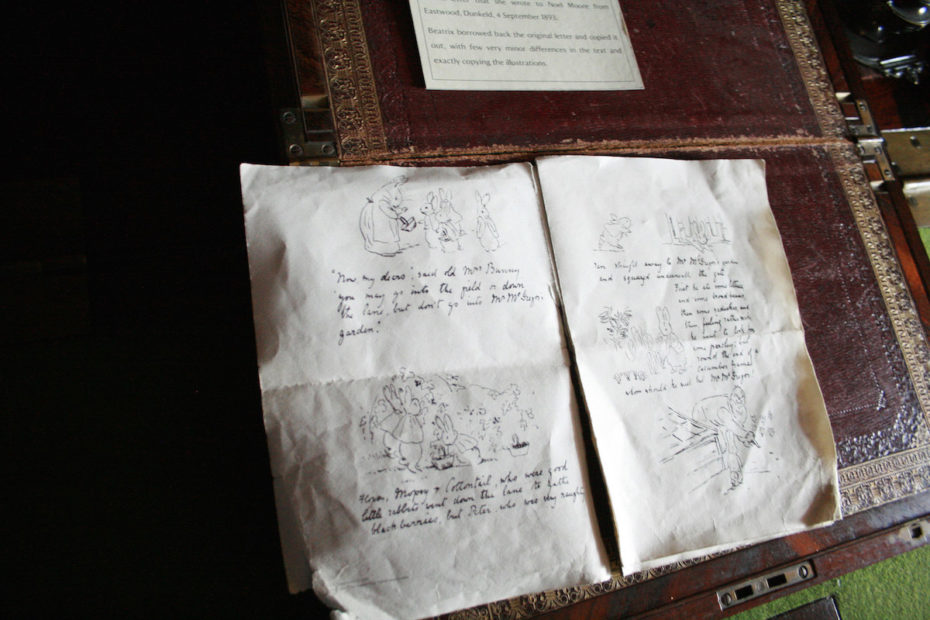

The house remains pretty much unchanged, with Ms. Potter’s famous doorway just as tangled in plants as ever. In fact, the descriptions of the vegetable patches are so detailed in Potter’s books, that the current gardeners still use them as a verbal blueprint for the grounds…

Step inside to see the dollhouse described in her 1904 book, The Tale of Two Bad Mice, in which some cute vermin bust into a doll house and smash every ceramic plate and pastry to bits. It’s said that when Potter wrote it, she was at her wits end living with own parents (she was in her thirties) and the story was a reflection of her need for independence.

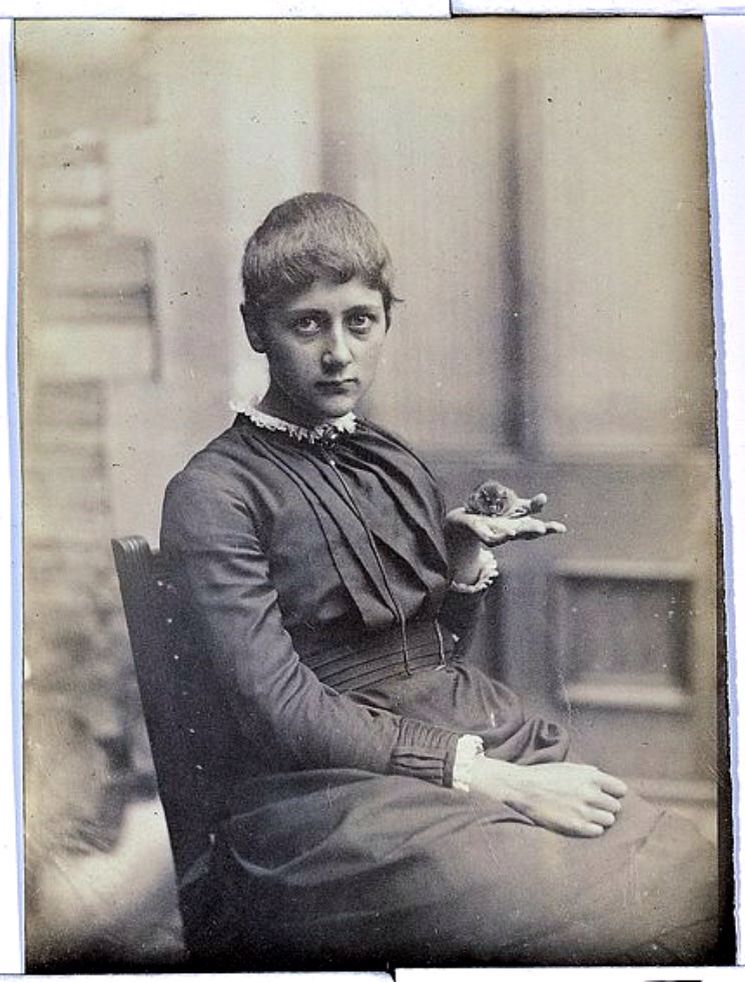

Potter was born into an upper class family, but isolated from a lot of interaction with other children. Instead, she was mainly raised by her three governesses. It was her time spent in Scotland and the Lake District that made her fall in love with animals, as well as botany.

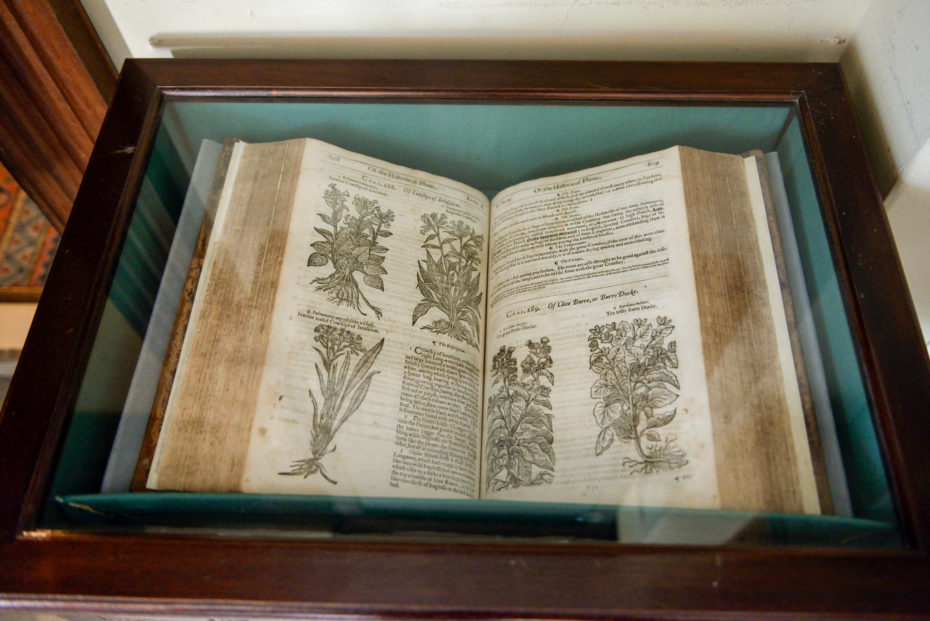

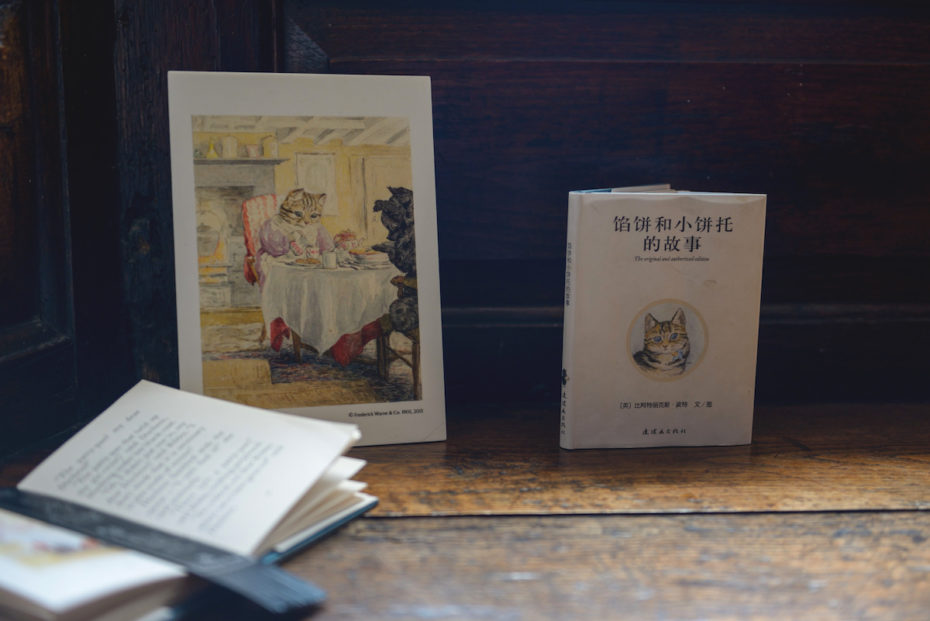

In fact, before she made all that bunny money and split for the country, she became a respected illustrator and mycologist– as in, the study of fungi. Potter was simply enchanted by the idea of creating whimsy on a smaller scale. In one corner of the house you’ll spot a collection of thimble-sized pots; in another a tiny dresser (on top of another dresser). She even made sure her books were small, so that children could hold them in their hands, and made a refreshing call to action to protect the worlds — real or imagined — taking place under toads stools, on lily pads, and down rabbit holes…

Above all, explained book critic Adrian Higgins in 2016, “What glues Potter’s tales together is her art. Anthropomorphic but also morphologically rendered, Potter’s animals capture the soul of the Edwardian countryside. It is a natural world that is deeply embedded in the English psyche” that went on to be translated into books of 35 languages, with over 100 million copies in print.

Not bad, eh? Be sure to check out the rest of the surrounding area of Hawkshead, the 12th century village that Potter called her stomping grounds. You can even stay at Buckle Yeat, now a B&B and restaurant, that she loved and featured in her writing: