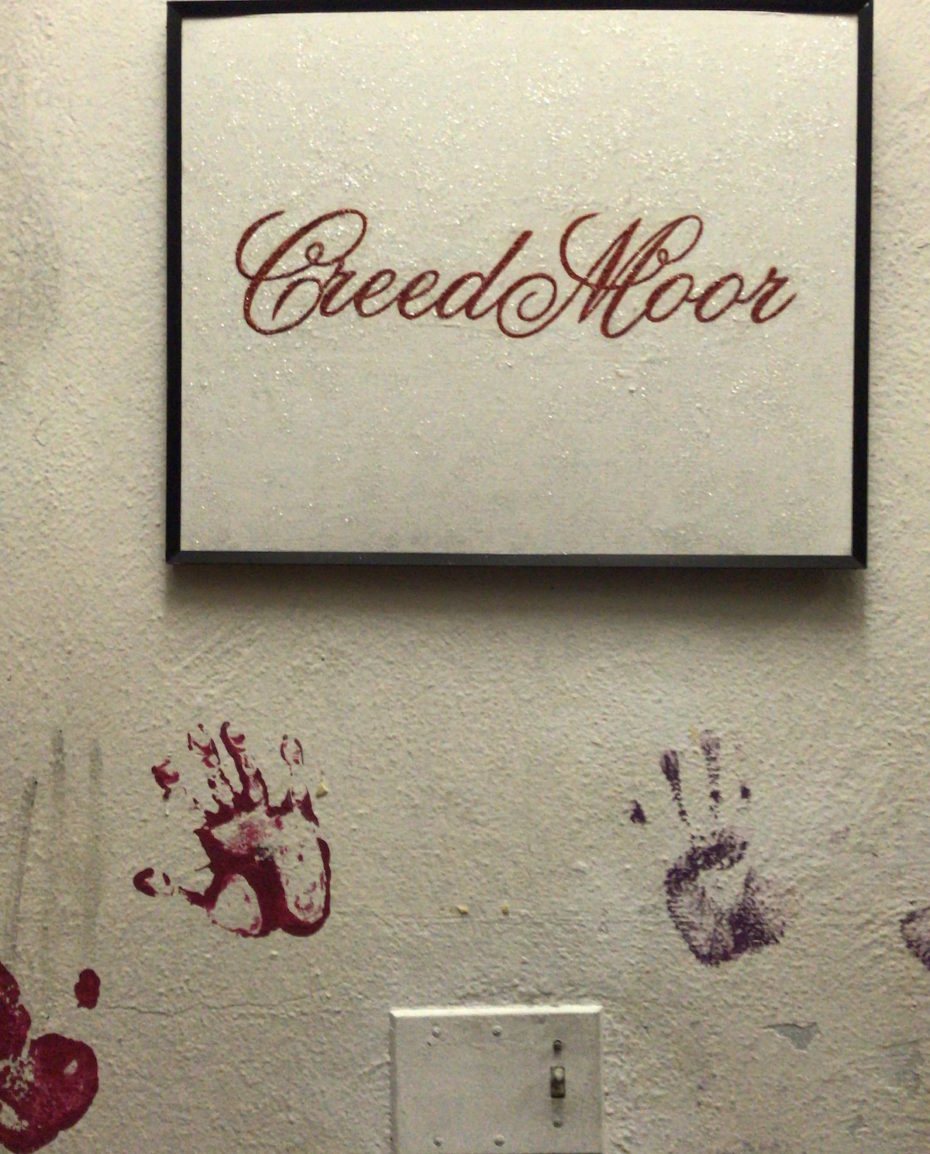

Creedmoor, NY

“Excuse me!” says a man by a snowed-in dumpster. “Excuse me,” he continues, in a teleprompted tone, “Where are you, excuse me, goodnight!” It’s 2pm at the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens. I tell him I’m lost, and pull out a map of the 300 acres where he is a patient, and where I’m late for my own appointment with Dr. Janos Marton. Creedmoor is the largest live-in mental asylum of its kind in New York, as well as its most infamous; it’s where the American singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie died, and where Lou Reed went through electroshock therapy.

This article contains violent descriptions that some may find triggering.

At its peak in the 1950s, it housed 7,000 patients. By the 1980s, it was literally killing them. Dr. Janos Marton dove head-first into that hell, combatting it with the creation of his “Living Museum.” Founded in 1983, the museum is an active studio space for patients to sculpt, sew, and paint their stories. It’s also welcoming of anyone curious enough to enter Creedmoor’s labyrinth, and find its entry at building #75. Just look for the door plastered in faces…

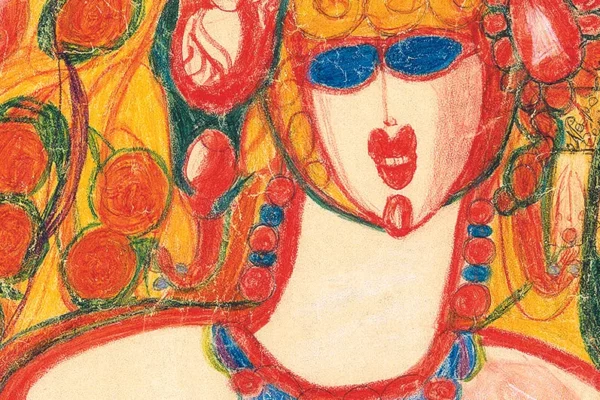

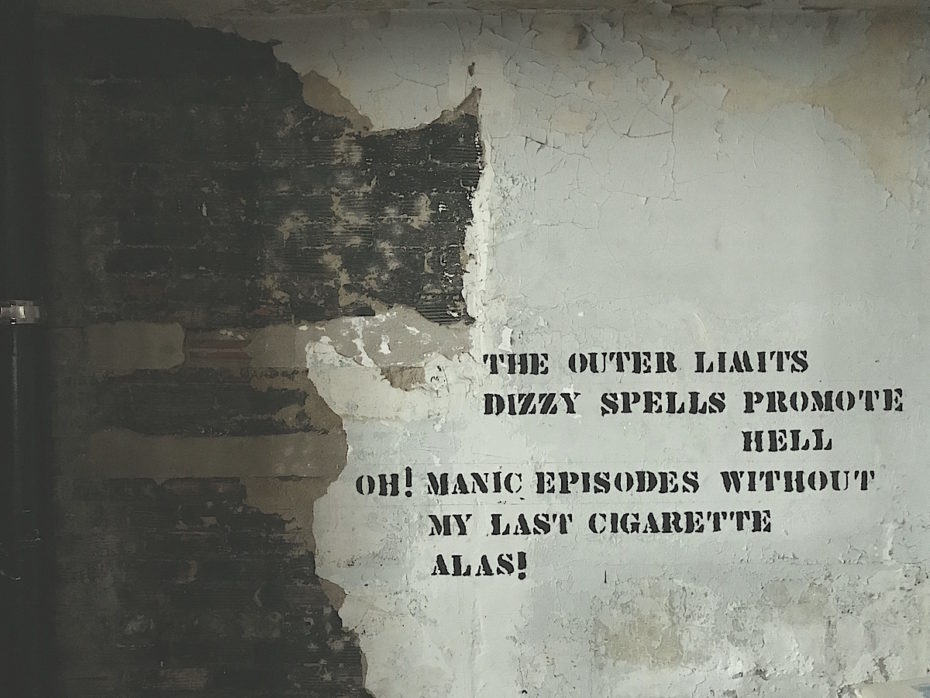

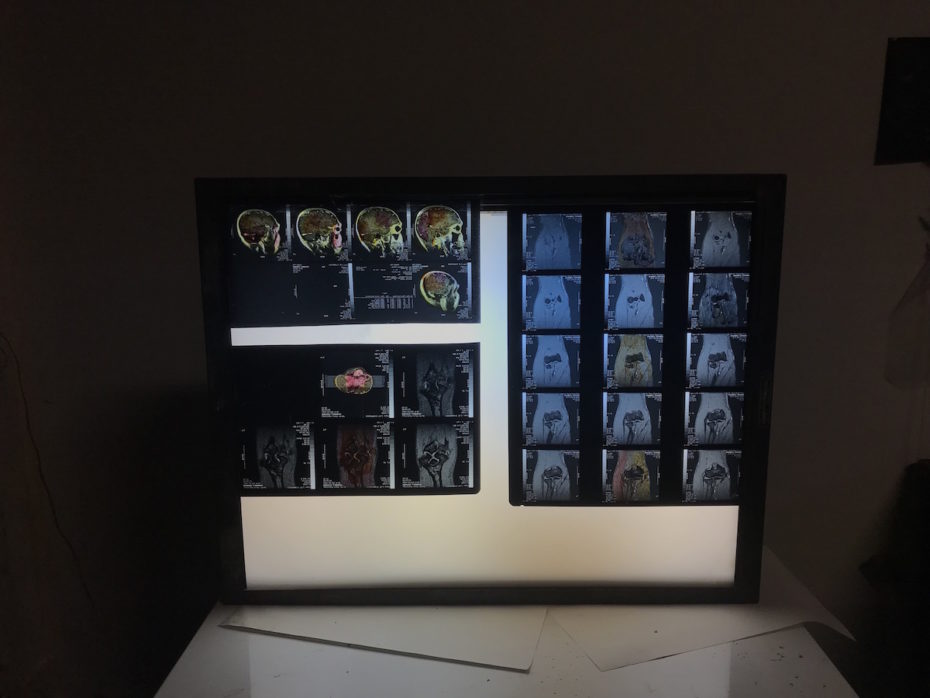

Inside, the senses go into over-drive. Lamps light up row after row of brightly coloured work stations, while painted pathways and arrows guide you through an eternally green jungle room, a reading nook with endless copies of National Geographic, and corridors wallpapered with poetry.

There’s no corner that isn’t for art. A lot of it is beautiful, a lot of it is scary, and none of it is boring. It all feels a bit like stepping into the tunnel scene of Gene Wilder’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The space is endless, and at first, silent. In one hall, an anonymous note is tucked under an easel, reading, “glad to see you have a space here now. hope all is well.” I jump when an unseen speaker starts blasting oldies, specifically, Be My Baby by the Ronettes.

Suddenly, a woman in a breathing mask appears, pushing a shopping cart through the rooms and gathering 1950s Christmas decorations, abandoned trophies and broken disco balls. In another, a man paints in silence with his head down, cozied up in a technicolor beanie. But still no Dr. Marton.

It’s as if the more you walk in to the studio, the more it opens up to you, and when the song’s chorus arrives all the patients sing in unison, “So won’t you, please! Be my, be my baby!” like an unofficial roll call. “I see you’ve made it,” says a man behind me in a Hungarian accent, “How are you?” At long last, our doctor.

Dr. Marton The Living Museum NL

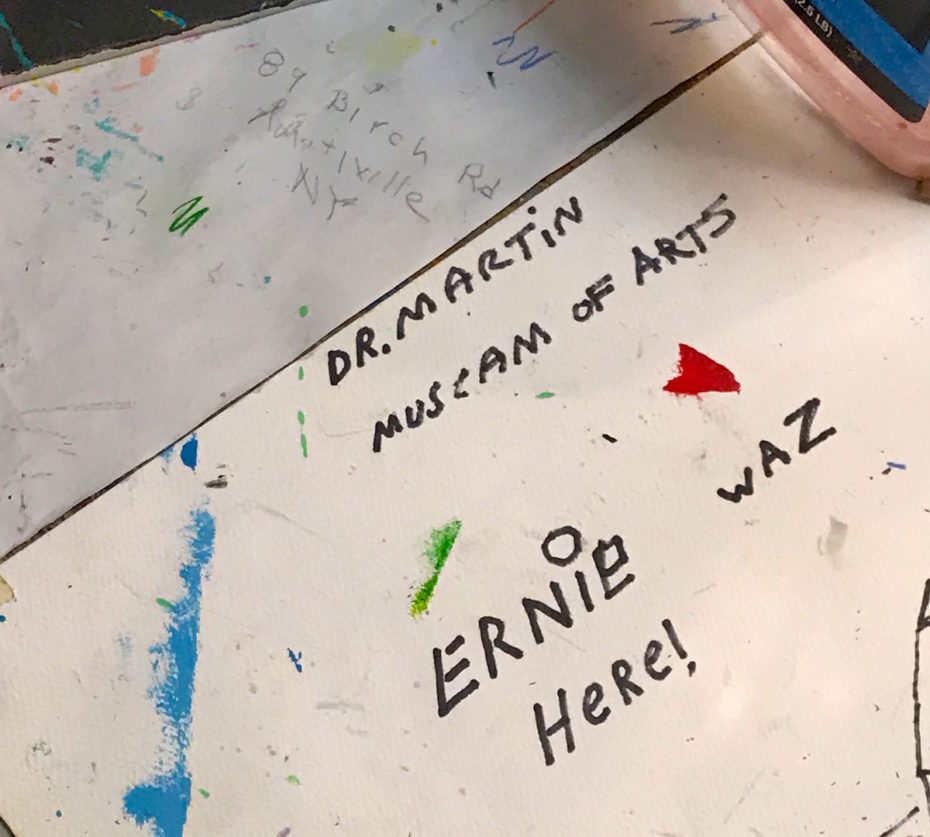

He introduces me to his colleague before observing a patient painting (a deer? a dog? a donkey?) on a concrete wall. “Hi, I’m Paula,” she says, shaking my hand, “Nice to meet you. Did you see my desk upstairs?” I didn’t even know there was an upstairs, I say. Dr. Marton stares at her work, “Very good Paula. Just don’t make it cutesy… that’s just Soviet Style propaganda.”

“You know,” he tells me, “In Switzerland they give bipolar patients donkeys, and schizophrenic patients horses.” I tell him I’ve heard donkeys are cuddly. “Oh yes, and smart,” he says, “The rabbits of the equidae family.” (Latin for horse).

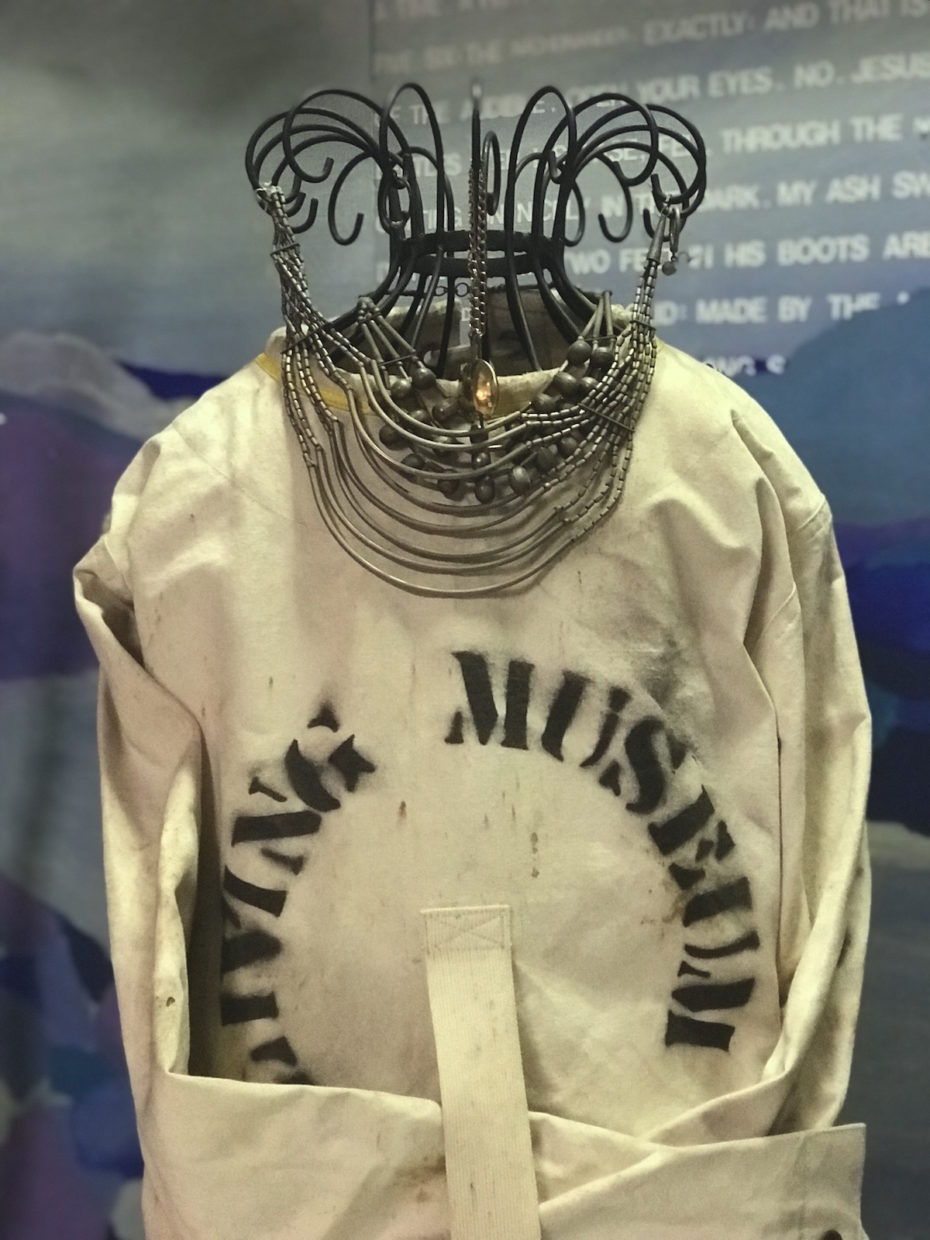

It’s the kind of sharp, albeit boggling critique that’s made Dr. Marton’s Living Museum so very alive, and a model for other art therapy ventures (there’s now a “Living Museum” in the Netherlands). But don’t use the words “art therapy” in front of him — this is a place where everyone is an artist before they’re a patient, which isn’t to say Dr. Marton doesn’t recognise the importance of that duality. He just doesn’t want anyone to feel contained by their illness. Instead, he hands out straightjackets for canvases:

He’s been Director of the museum since 1995, when his co-founder, the artist Bolek Greczynski, died. Dr. Marton has both a Ph.D in Psychology and an M.A. in Fine Arts from Columbia, but you could say it was also his roots in Eastern Europe, and the memories of Communism, that steered him towards art as a tool for liberation.

“He’s the son of a dissident economist who was taken off to prison for six years on the day of his son’s birth,” explains Erica Goode in a 2002 feature for The New York Times. Both Greczynski and Marton sought asylum in New York, and immediately found their way into an Art Brut scene inspired (in part) by the bygone Surrealist artists of Europe. “We were the children of Marx and Coca Cola, rejecting both,” Dr. Marton told his alma mater in a 2013 interview.

And by the mid-Seventies, Creedmor was crumbling in every sense of the word. Building #25 was completely abandoned (and still is), and in 1984, The New York Times reported that “after several reports of widespread brutality against patients, [a] secure unit was shut down,” when a mentally ill patient was found dead “while bound in a cloth straitjacket, his throat crushed” by staff.

It was a horrifying reality check on the abuse and mismanagement so common in healthcare facilities, and specifically, on such a large, state-run scale. “Regulations about medication were ignored,” reported the Times, and there was “dangerous understaffing in a ward that housed the most violent, most severely ill patients” in the country. Creedmoor also had (and still has) an open-gate policy with patients, which means that if no one is keeping tabs on their whereabouts — well, you get the idea.

In heart of that chaos, Greczynski and Marton dared to fight for a safe — and joyful — space. “The two guided the transformation of an abandoned building,” states the Columbia interview, “They took down the paint peeling off the walls and the layers of dust clouding the windows. Some rooms were inhabited by squirrels, others were locked and inaccessible. [They saw] through the grime.” That optimism is stronger than ever today, along with an exciting sense of freedom for both patients and visitors.

After our chat, Dr. Marton lets me explore the studio on my own (and trust me, it takes over an hour). And as for the quality of the art? “I think that the idea of talent is overrated,” he explained in his Times piece for Goode, “The traditional definition of art and what is good art and what is valuable art went out of the window with Marcel Duchamp.” Touché. Also, who doesn’t need a painting of an eagle fighting a swordfish?

“Art is not going to take away your mental illness,” he told Goode, “But it builds on the symptoms of mental illness. In the regular hospital setting, that is something they’d want to get rid of because that’s what makes you crazy, what defines you as a mental patient…But I celebrate those aspects.”

As I prepare to leave, a woman sitting at a table calls me over. She’s been doing calligraphy and sewing fist sized pin-cushions– both hobbies she says she’s had for ages. “Here,” she says, handing me a cushion, “I’m Chan. This is for you.” I thank her, but tell her I can’t sew. “Oh, that’s ok,” she says, “everyone needs a pillow.”

The Living Museum is open at 80-45 Winchester Boulevard, at Building #75, Mon-Thurs, 10am-12pm and 2pm-4:30pm by appointment only (call +1 718-264-3490).