You probably know Guggenheim– the name, the museums, the collections– but do you know the woman behind legendary the name (and sunglasses)? Peggy Guggenheim didn’t live the domesticated life that was expected of an heiress. She was her own kind of bohemian, impossible to define, mysterious and in many ways, tragic in her loneliness. But her life was without a doubt, one long, dazzling adventure…

The woman who created one of the most influential collections of the twentieth century was born in Manhattan, to an aristocratic German family that owned one of the largest fortunes of the 19th century thanks to clever, early investments in silver mining. Her mother, Florette, is remembered for repeating everything three times, from her sentences to her clothes. Her Aunt Fanny used to sing everything, and Ernest Hemingway even based one of the characters in his book, The Sun Also Rises, on her cousin, Harold Loeb. As for Peggy? She abandoned the prospect of university to work, unpaid, at a bohemian, Greenwich Village bookstore.

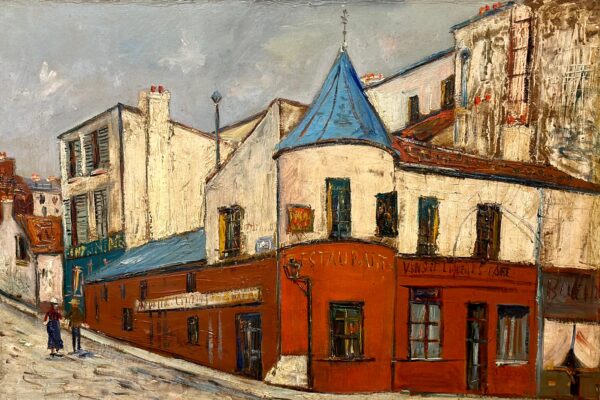

At 21 she split from New York to live the ultimate bohemian dream: Paris. With her inheritance in tow, she was in good company. It was the height of the Jazz Age and the place to be for the emerging French Avant-Garde scene of the 1920s; the cafés and salons overflowed with writers, artists, architects and anarchists. Man Ray photographed her, and Marcel Duchamp encouraged her to invest in new artists that the public was rolling its eyes at, like Dalí, Magritte, Mondrian and Kandinsky.

Her plans to open a gallery in Paris were abandoned as the Nazis encroached on Paris. With her growing collection of art, she went to the Louvre in the hopes that the museum might safeguard her eclectic pieces alongside the Venus de Milo and the Mona Lisa, but her request was denied. Peggy was left no choice but to hide her artworks inside a friend’s barn outside of Paris.

She had been acquiring new works almost every day, right up until the city fell to Hitler. In the midst of making arrangements to get her art safely back to New York, she fled Paris at the 11th hour as her beloved city closed the curtains on a legendary era for the Avant-Garde movement.

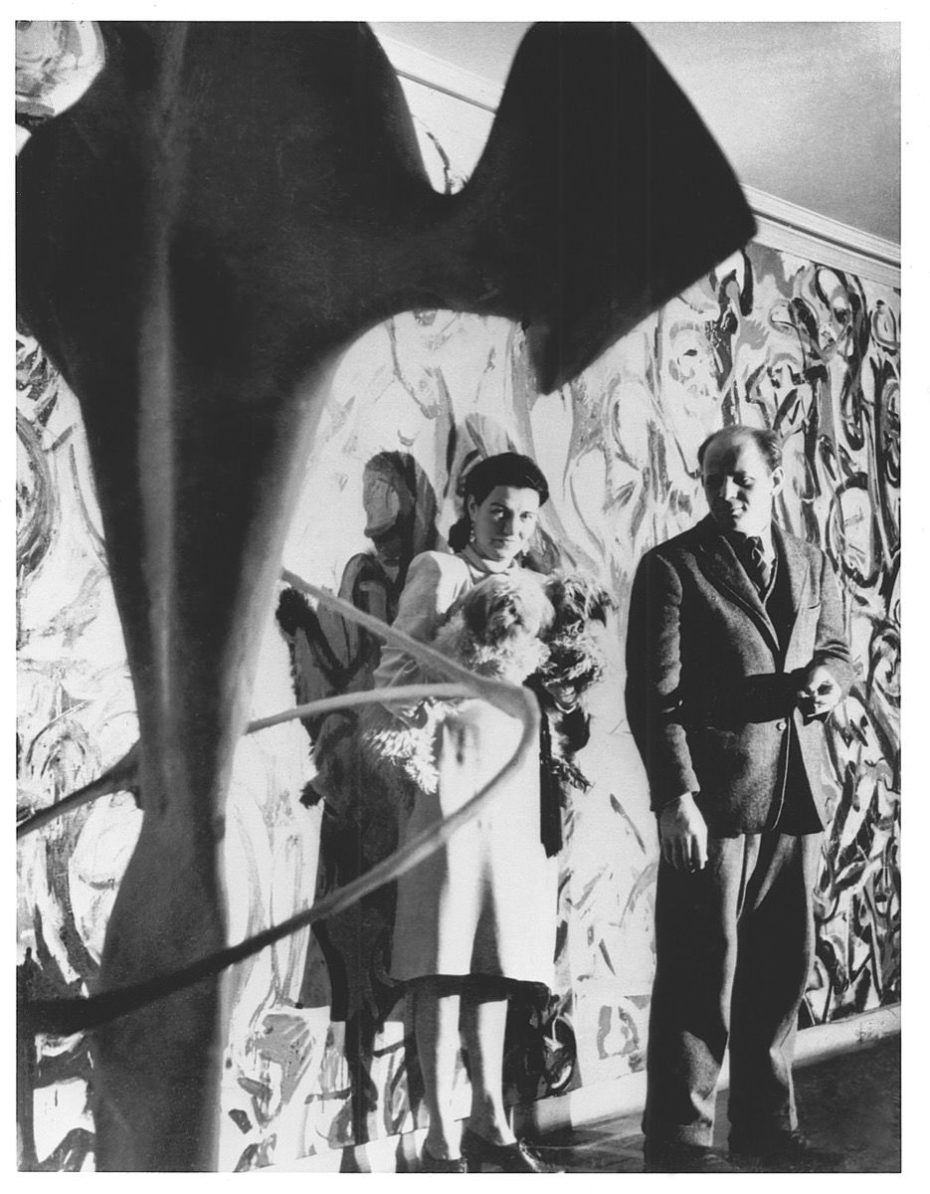

Back in New York, she would be the one to discover Jackson Pollock, become his patron and host his first solo exhibition at her gallery, Art of This Century, which is also where she opened one of the first exhibitions spotlighting female artists. But New York was a different playing field for women in the art world.

In a 2017 article for The Guardian, Judith Mackrell said “[Guggenheim] had routinely been patronised by the city’s very male, misogynist art scene. Too often, her gallery had been belittled as a rich woman’s vanity project, and too often she had found herself the butt of blatantly sexist and antisemitic attitudes.”

Peggy was also a self-proclaimed nymphomaniac (a lifestyle she picked up in Paris, some suggest) and is said to have bedded around 1,000 men and women. She had flings with artists, writers and war heroes. There were the leaders of the avant-garde like Laurence Vail, with whom she had two children. There was Samuel Beckett, who, along with Marcel Duchamp, was one of her early champions, encouraging her ambitions as a collector. But she had a troubled marriage to the surrealist, Max Ernst, who took advantage of her status, and brazenly admitted that his marriage to her was merely a career move.

Her love life was messy, no doubt. We think there’s an epic biopic movie waiting to be made about the complicated love life of Peggy Guggenheim (someone call Meryl Streep). She was very open about her promiscuity, and never tried to hide the fact that she had seven abortions. No one was talking openly about such things at the time and she was punished for it. But that was Peggy– never one to shy away from the truth; “unusually direct and forthcoming about the most personal things”.

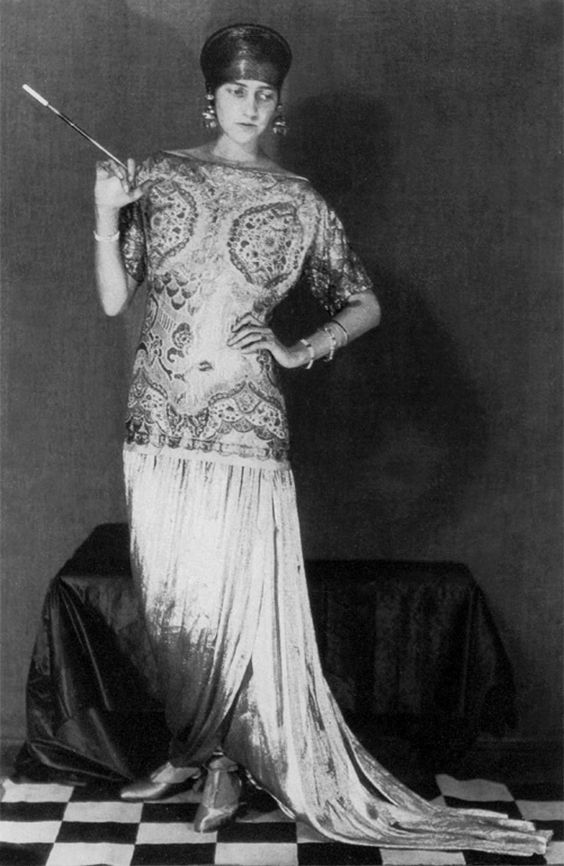

Her personal style mirrored that. She was fabulously eclectic, and always colourful. She wore Elsa Schiaparelli cellophane-wrapped dresses, eccentric sunglasses you’d find on the Gucci runways today and big statement earrings, which she hung like art on her bedroom walls.

That was her signature style: to look like a walking piece of art. At her New York gallery opening, she wore two different earrings to make a point about art, saying, “I wore one of my [Yves] Tanguy earrings and one made by [Alexander] Calder in order to show my impartiality between Surrealist and Abstract Art.” Peggy was living proof that fashion only gets better (and more fabulous) with age and experience.

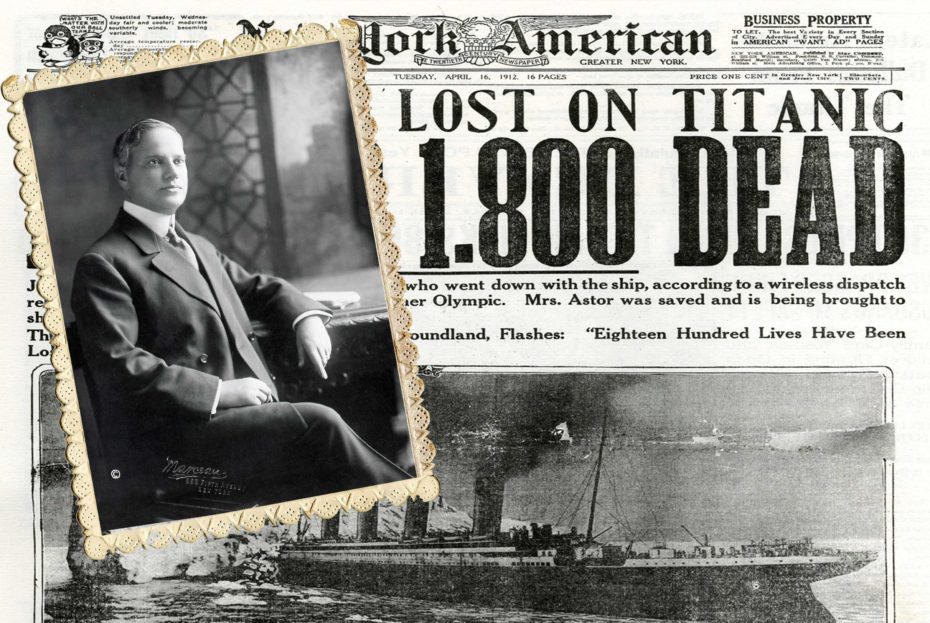

She almost certainly inherited a flair for fashion from her father, Benjamin Guggenheim, who was allegedly smoking a cigar and dressed in his evening suit as the Titanic went down. “No woman shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward,” he is quoted to have said. “We’ve dressed up in our best and are prepared to go down like gentleman”.

Peggy was only 14 when he died on the ill-fated liner, and his body was never found. Her move to Paris in her twenties may have been an attempt to reconnect with the father she’d lost: Benjamin, whose family reportedly controlled up to 80% of the world’s silver, copper and lead mines, kept an apartment in Paris (as well as a mistress), and even helped build the elevators in the Eiffel Tower. “I adored my father,” Peggy wrote, “but I suffered very much because he made my mother unhappy”. In a 1998 article for her great-grandmother’s museum, Karole Vaile said she believes Paris was Peggy’s way of escape a deeply unhappy family.

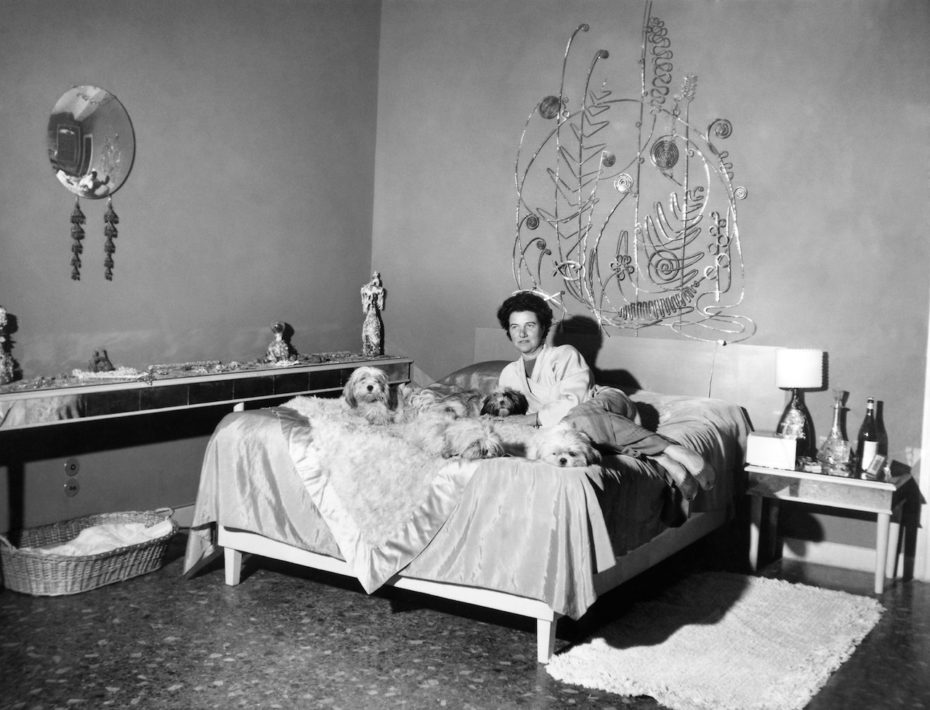

Peggy’s numerous homes around the world were like art galleries themselves; filled with treasures. Major works from her collection were sprinkled around her New York apartment. You’d find a Pollock casually hanging in the hall, a Max Ernst in the living room, and bedroom headboard made by Alexander Calder.

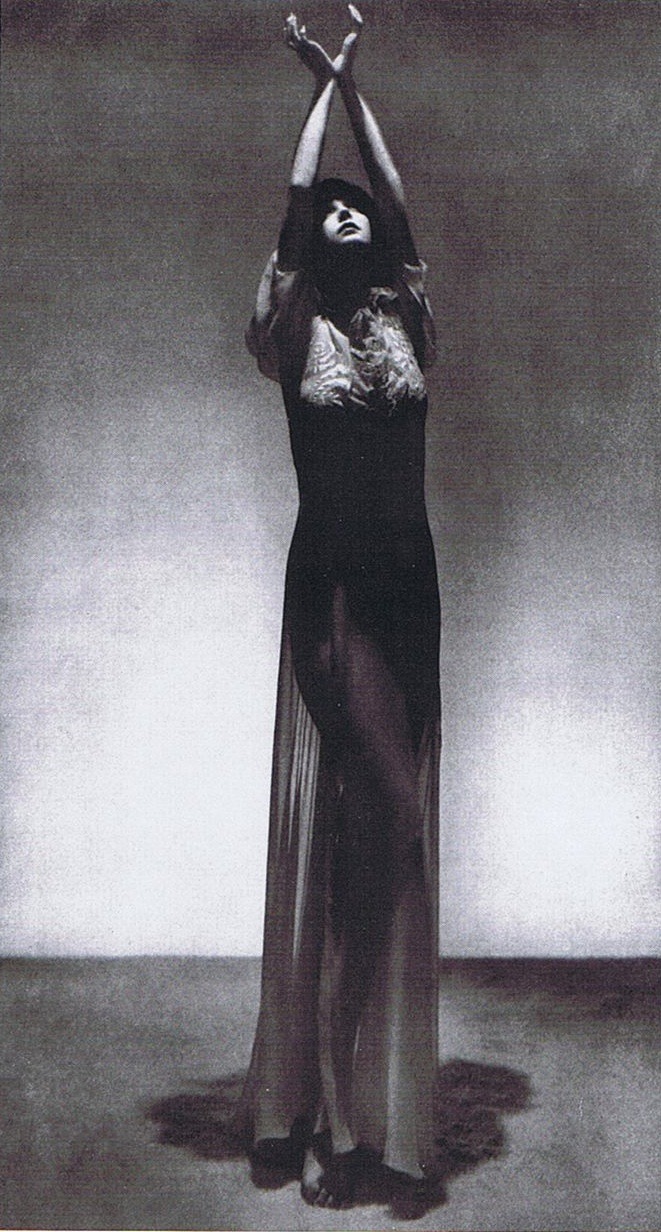

The city of Venice became Peggy’s last love and final destination, as well as the guardian of her collection. She moved into the former palazzo of Luisa Casati and drifted through the canals on her private gondola as the sinking city’s bohemian queen.

Dressed to the nines, she was always accompanied by her dogs, or as she said, her “beloved babies” and most-trusted companions. She had fourteen in her lifetime, with names like “Hong Kong”, “Peacock” and “Madame Butterfly”.

It’s impossible to imagine what the art world would be today without Peggy, but it certainly wouldn’t have been as fun. Still as influential as ever, just this year, Vogue published an article on How, And Why, To Dress Like Peggy Guggenheim, and her ability to foster both cutting edge and female artists made her a true pioneer in the industry.

That Peggy was also the last person in Venice to have a private gondola is deliciously symbolic: she epitomised an era of eccentricity, and luxury, that will never repeat itself. But upon her death, that eccentricity was shared with the larger public with the conversion of her Venice home into a museum. Now, folks from around the world can bask in the Francis Bacons by her mirror, or the Picasso in her hall, walking in the footsteps of one of the last great art collectors.