As it turns out, the French Riviera caters to more than a few of our favourite holiday past-times: channeling Brigitte Bardot, building sand castles at the beach and … tracking down aliens? About an hour north of the seaside city of Nice, into the mountainous terrain where Provence meets the Cote d’Azur; at the end of a steep and windy road, an otherworldly moonscape awaits.

There, several mysterious and futuristic domed buildings are scattered around the rocky grassland– each one controlling various telescopes and lasers belonging to the Côte d’Azur Observatory, which has been credited for the discovery of 21 minor planets. You can visit anytime, so we say skip the beach on a crowded day and make your way up to this little-known lookout known as the Plateau de Calern, one of the few places on earth that can boast views all the way to the Mediterranean and past the planet Mars…

Of course, this wouldn’t be the French Riviera if its observatories didn’t somehow live up to the glamorous and groovy reputation of France’s iconic summer playground to the stars (no pun intended). Sure enough, the architect behind one of the most curious-looking buildings perched atop the rocky plateau is one you might have heard of– Antii Lovag, best known for his famous Palais Bulles in Cannes, aka, the iconic home of French fashion designer, Pierre Cardin.

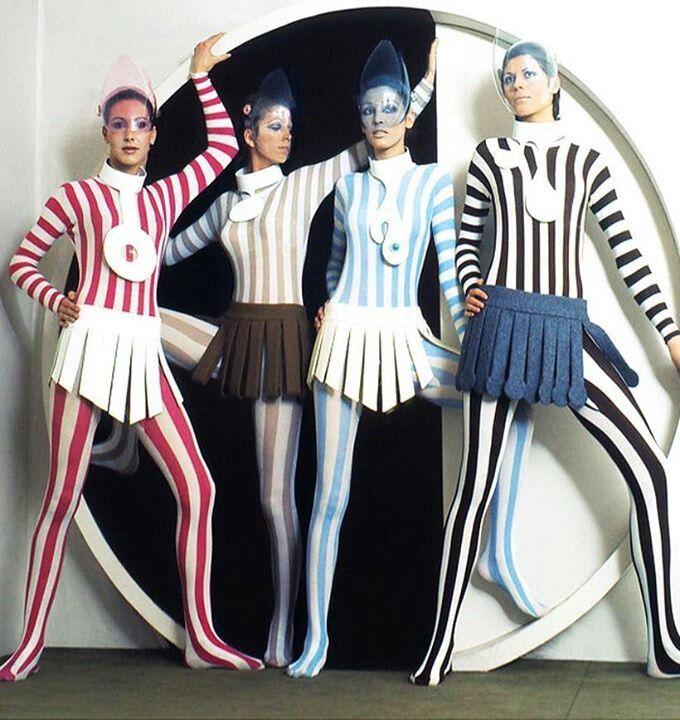

In the 1970s, the Côte d’Azur became the architect’s canvas for groundbreaking groovy structures fit for very chic extraterrestrials. There were his glamorous houses, beloved by designers like Pierre Cardin; with its 1200 square metres of rounded walls, and windows that feel like looking through an astronaut’s helmet.

It was the perfect match for the groovy designer, Cardin, who was designing the kinds of outfits you’d wear to a cocktail bar on the International Space Station. (The Palais Bulles can now even be rented by the lucky few for private stays and events).

Lovag pioneered what he called “bubble houses” to both the delight and confusion of the public. For Lovag, it was a step towards a more harmonious way of living. No sharp angles, no problems.

In 1971, he conceived of the Maison Bernard (built for a man named Pierre Bernard), which felt a whole lot like looking at the world through a rose coloured scuba mask on the French riviera. Today, the home is an artists residency, but is still open for public visits if you book ahead.

But Lovag actually did apply his space age vision to make an actual outer space observatory, designed for the plateau of Calern in the 1970s. It’s essentially as if he plopped one of his seaside homes in the middle of a moonscape.

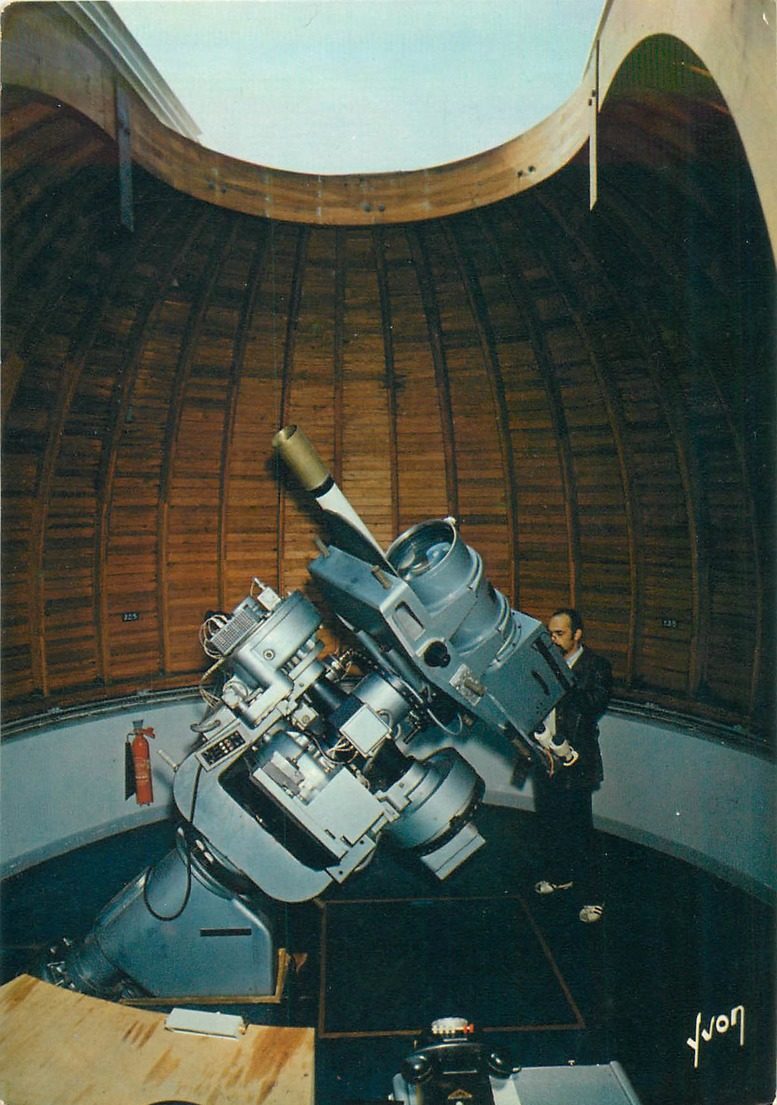

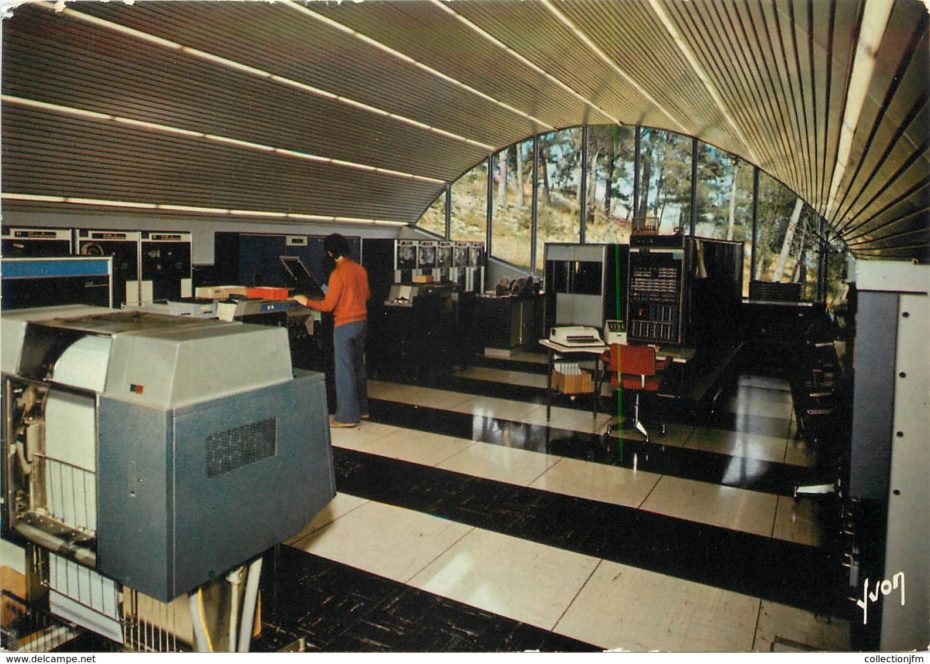

Since the 1970s, says its official site, Calern has been the guardian of revolutionary scientific instruments like the very powerful Schmidt telescope, used to detect astronomical objects, catalogue objects inside and outside our “Milkyway” galaxy and study the galactic structure.

If you visit the site any night that isn’t overcast, you’ll see the eerie sight of satellite laser pulses streaking up through the sky towards invisible satellites as they pass over. The satellite laser ranging is part of global network that measures the round trip time of flight of ultrashort pulses of light to satellites equipped with retroreflectors. From what we can gather, the data they gather makes them unique for modelling and evaluating long-term climate change by.

Lovag’s space-age Hobbit hole, known officially as the GI2T (Grande Interféromètre à 2 Télescopes) has a pair of telescopes to observe at visible wavelengths and studies the gaseous envelopes around hot stars, pulsating stars and very-close-together double stars.

While the Calern site can be visited at any time, to wander amidst the white domes and enjoy the great views, between May to September, tours of the observatory facilities are given every Sunday by the scientists who work there.

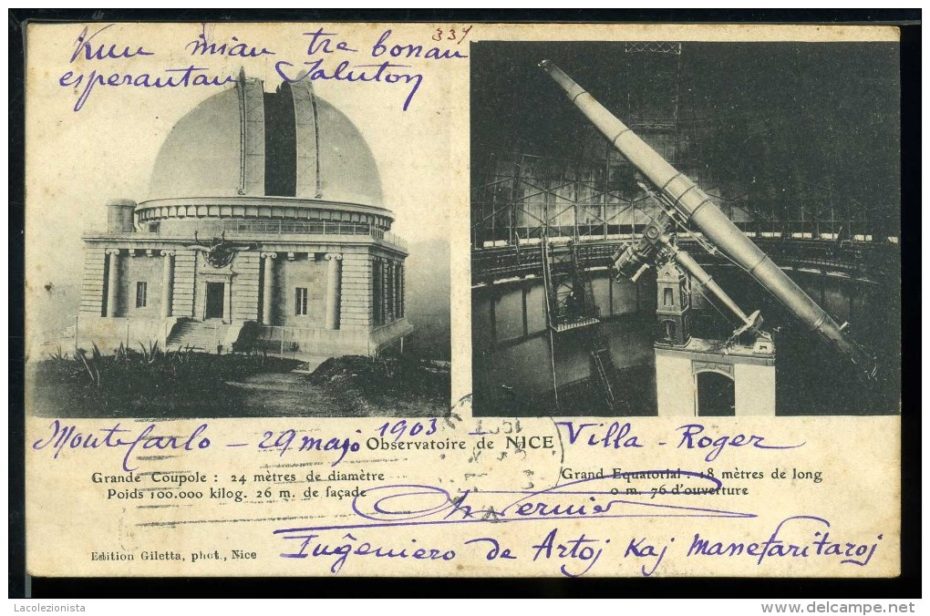

Lovag’s bubble observatory today belongs to the 130-year-old Côte d’Azur Observatory, a vast institution in its own right, which encompasses the Nice Observatory further up the coast, designed in 1881 by Charles Garnier and Gustave Eiffel (as in, the Paris “Garnier” Opera House and the Eiffel Tower).

Garnier’s job was to build the 24m rotating dome, which they had to crank open manually to look at the sky until the arrival of a motor in 1888. Eiffel, otherwise known as “the Genie of Iron”, made a genius contraption to move the telescope around: a little man-made lake upon which the coupole floated, allowing the 92-ton dome spun. That’s like whirling around the weight of roughly 20 elephants.

You can visit both observatory sites today, Eiffel’s at Mont Gros and Lovag’s at the Plateau de Calern to see their evolving, impressive technologies.

Learn more about visiting here. Learn more about visiting Maison Bernard here. These days, the Palaos Bulles is used for private events, photoshoots, and the like. If you’ve got the party of the century coming up, book it here.