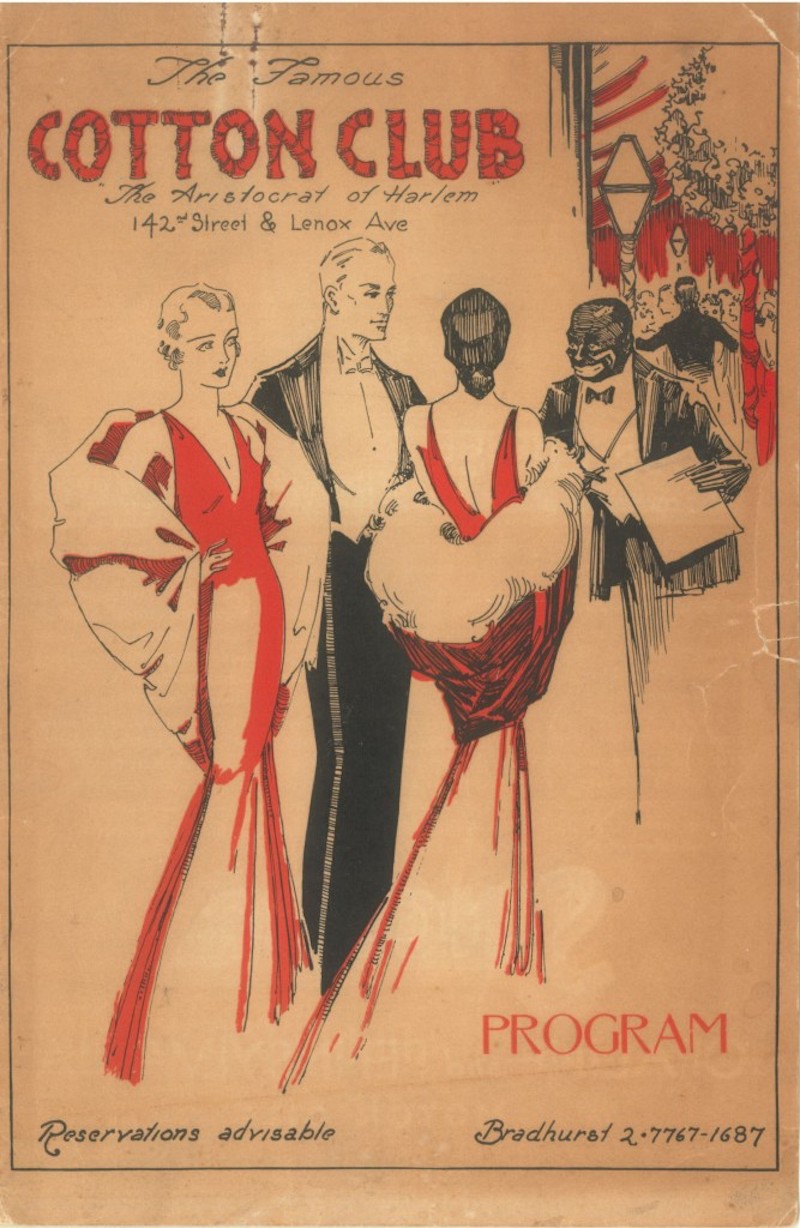

The 1920’s in Paris may have been roaring, but over in Harlem, they were stomping. New York’s playground was not short of an underground boozer, but there was one place in particular that dominated the scene; The Cotton Club. Patron Saint of jazz, notorious bootlegging and the home of the original Black Betty Boop.

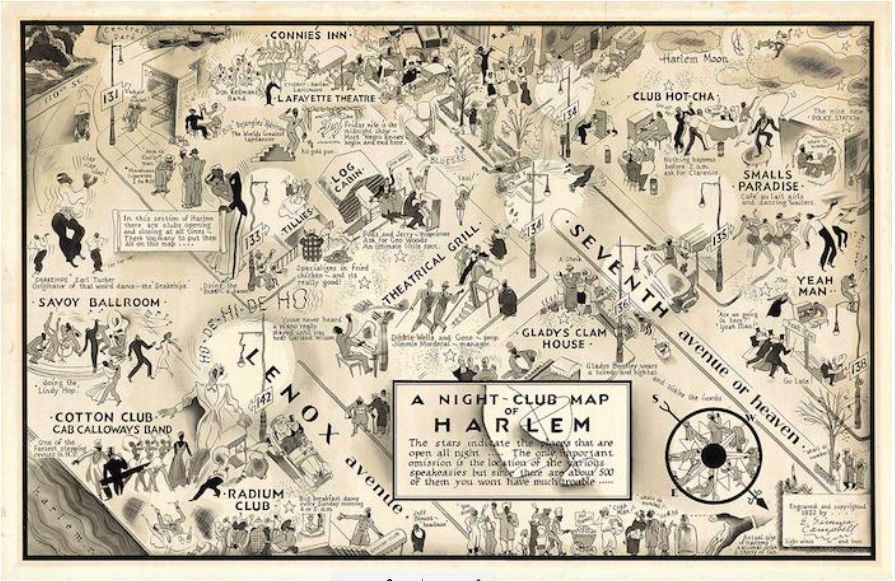

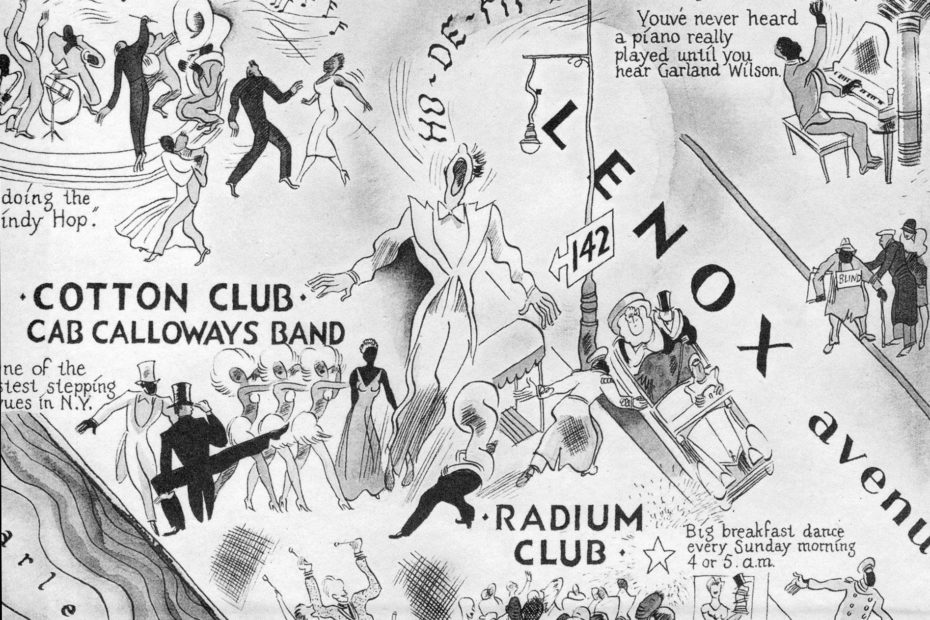

Harlem nightlife by cartoonist Elmer Simms Campbell, 1935 via Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

It was Harlem’s Renaissance and the African-American cultural scene was thriving– and it may have been the prohibition period but that didn’t stop the riches of New York seeking out their local speakeasy for a night of debauchery and dancing. The Cotton Club launched the careers of some of the most important African-American performers of the early 20th Century, and the legendary music venue became the beating heart of the American jazz age…

Situated on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue, the venue was first known as Club Deluxe before Irish gangster Owney “The Killer” Madden came along and muscled out the previous owner, Jack Johnson (the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion). Fresh out of prison, Madden was big into bootlegging and he’d found the perfect place to hustle his hooch. Along with his notorious partner in crime, Big Frenchy DeMange, they renamed it “The Cotton Club”, a flagrant ode to the cotton farming industry and its predominantly Black workforce.

Limousines pulled up to the venue and out would step the white and wealthy, dripping in ermine furs, fancy flappers and gibus top hats. But the taste of these times is bittersweet. Though the club created a platform for emerging Black musicians to be seen and heard, behind the bright smiles and flowing champagne, there was a less than cheerful reality to the festivities.

A program for the club, 1932. New York Historical-Society.

The premise was black and white, quite literally; Black performers were hired to entertain and serve a white-only audience. Musicians were finally being recognised for their talents, but the performances often fuelled African American stereotypes, playing up to the “exotic savage” or the cotton pickers of southern plantations. Segregation was rife off-stage too, and the performers were rarely permitted to mix with the clientele socially after the show.

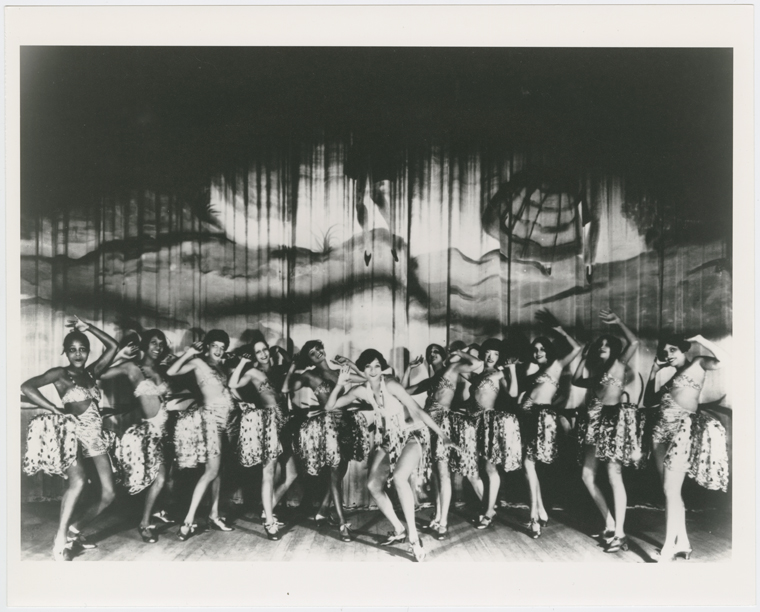

Stepping into the horse shoe-shaped room immediately transported you into a jungle themed spectacle, or as one writer described, “a brazen riot of African jungle motifs, southern stereotypology, and lurid eroticism”. The club itself was designed by architect Joseph Urban (the same guy who built our abandoned gingerbread house in New Jersey), who was passionate about theatre design. Lavishly decorated to cater to the New York elite, it was a theatrical playground that nevertheless saved centre stage for Harlem’s finest performers…

Cab Calloway and his dancers

The Cotton Club hosted no less than the best of the best. Names on the marquee included Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, Dorothy Dandridge and many more. Before the pre-Paris peak of her career, flapper Queen Josephine Baker even graced the stage.

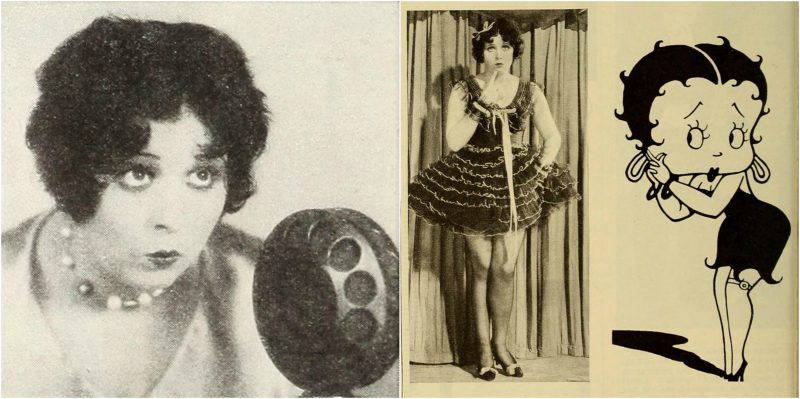

Another performer at the club (pictured below) was Esther Jones aka Baby Esther, aka the unsung inspiration for Betty Boop. She was already a hit in Paris by 1929 when she headlined at the Empire Theatre. A local newspaper wrote that she “has been heralded as the child wonder of Paris and is creating a sensation wherever she appears.”

Esther Jones aka Baby Esther aka Betty Boop

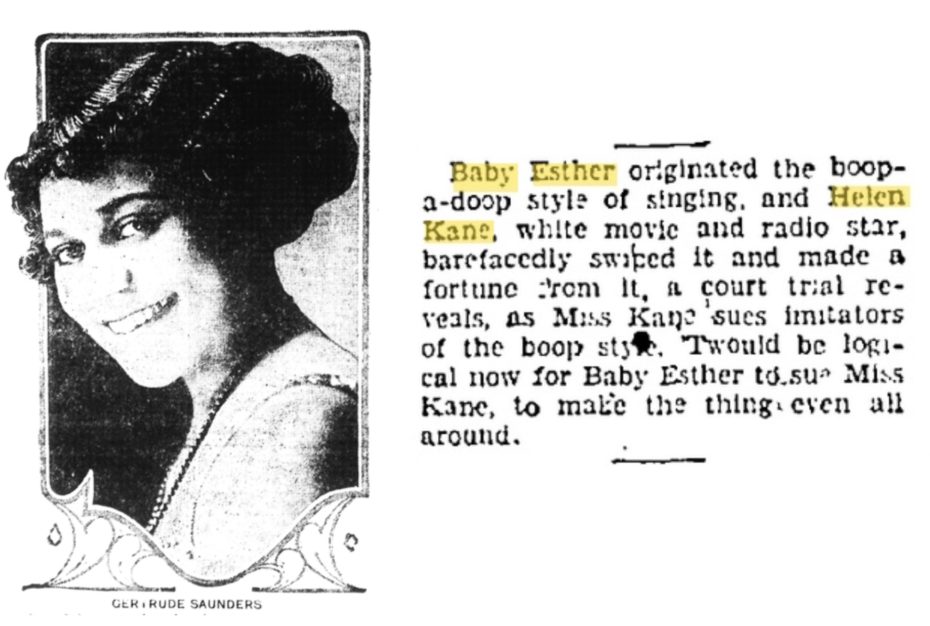

Tipped to be the next Josephine Baker, her real name was Gertrude Saunders and African American historians believe that she “coined” the famous words “Boop-Boop-a-Doop”, first uttering them on stage at the Cotton Club. Jazz studies scholar Robert O’Meally, referenced by the Harlem World Magazine, even referred to Saunders as Betty Boop’s “Black grandmother.” But somewhere between 1927 and 1928, a white Broadway actress and singer, Helen Kane, caught one of Esther’s performances and almost immediately began using the “boops” in her songs.

Helen Kane

In 1928, Kane recorded a song called “I Wanna be Loved by You”, which brought her sudden fame and notoriety as the ‘Boop-Boop-a-Doop Girl’ thanks to a unique vocal improvisation that could be heard after the chorus of the hit song. This style of “scat singing” was entirely new to white American audiences, unless of course, you’d been hanging out at the Cotton Club in Harlem, where Baby Esther and her pals had been doing it since the early twenties.

Enter the man behind the iconic Paramount cartoon, Max Fleischer, who claimed that when he created Betty Boop, she was purely a creature of his own imagination. Now, we can’t claim to know what went on in the mind of this famed animator, who is also notable for creating “Popeye”, but we did some digging and found that Fleischer moved in the same circles as many notable Cotton Club performers. And what we do know for sure is that Cab Calloway, one of the original Cotton Club performers, actually collaborated on the music with Fleischer, starring in three shorts with Betty Boop herself:

The above recording starring Cab Calloway also features the voice of Mae Questel, a young vaudevillian who was selected by Fleischer to play Betty Boop after winning a “Helen Kane Impersonation Contest” (possibly covertly organised by Fleischer himself). At the 2:19 mark, take a listen to Mae’s singing voice as Betty, then have a listen to a Helen Kane recording and see if you notice any similarities.

Helen Kane, left; Grim Natwick’s original Betty Boop sketch, right

Grim Natwick, the hand that originally sketched Betty Boop, recalls Fleischer handing him a song sheet “I Wanna Be Loved By You,” and asked him to draw a girl character to go with it. Grim began sketching a French poodle with a head of curls à la Helen Kane. In the very first episode, Betty Boop did in fact appear as a curvaceous canine waitress, singing in a fancy restaurant. The cutesy character quickly morphed into a sexually suggestive flapper girl, effectively becoming the cartoon doppelgänger of Helen Kane. Enraged and nearing the end of her career peak, Kane promptly filed a $250,000 infringement lawsuit against Fleischer and Paramount.

The trial played out like a Broadway comedy. The press ate it up as numerous celebrity entertainers were summoned to testify. Sure enough, “Baby Esther” got wind of the trial and her own claim as the true inspiration of Betty Boop actually helped boost Fleischer’s defence that Helen Kane’s act was not unique. Numerous performance recordings were used as evidence and Kane was even made to perform her version of the “boop-a-doops” before the judge. The court reporter famously struggled to document the unusual courtroom proceedings on his stenograph.

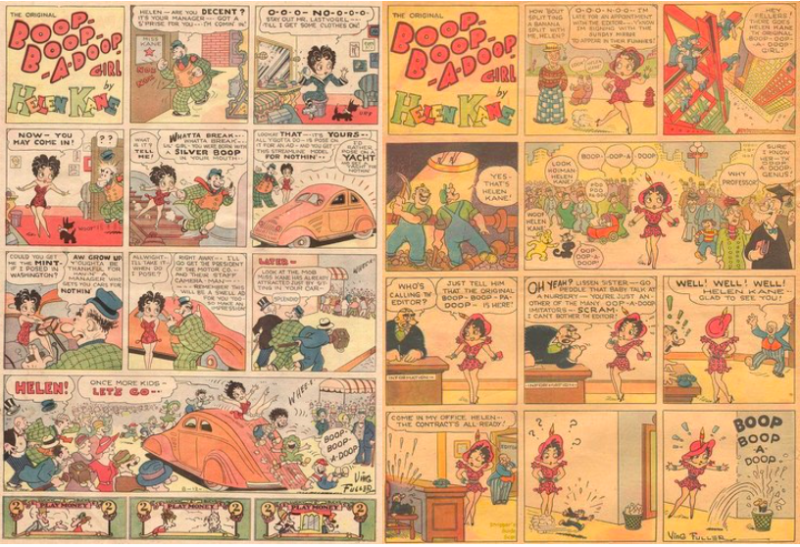

There was so much to-do about who was the true inspiration behind Ms. Boop, it truly deserves its own book. Did Fleischer himself see Baby Esther scatting her way to the hearts of the Harlem with her boop-a-doops and child-like charm? Helen Kane very likely “borrowed” Esther’s style and perhaps karma did its work when Max Fleischer in turn “borrowed” it too. In the end, neither woman would win the right to call herself “the true Betty Boop”. Despite what would make a strong case in a courtroom today, Kane lost her trial for failing to provide enough evidence that her own likeness was unique. In defiance of the judge’s verdict, she brazenly created her own comic following the trial and called it ‘The Original Boop-Boop-A-Doop-Girl by Helen Kane’, which we dug up for you below:

So where does that leave the Cotton Club darling, Gertrude Saunders, aka Baby Esther? Unfortunately, her name has been largely left out of Harlem Renaissance history, and there are no early sound recordings of Esther’s “Boop” performances that exist online (although footage was allegedly used at trial to prove Kane’s character was not unique).

And while the Betty Boop we know today was inevitably whitewashed for white American audiences, we did find some early episodes where the provocative cartoon appears with a distinctly darker skin tone:

We often assume Betty Boop has always been a household name, but Paramount actually retired the character way back in 1939 and she didn’t reappear on screens until the 1970s when she was rediscovered as an iconic figure of the past. By then, the true story of her Harlem roots were well buried. As for the notorious club that may have been her birthplace?

After 13 years of hot jazz and illegal booze, the Cotton Club closed its doors for good on February 16th, 1936 in the midst of the Great Depression. It was no secret that the club entertained a not-so-sober clientele during the prohibition and the venue was already hurting from regular closures. Though Cotton Club was certainly a paradox between opportunity and oppression, the almighty talent that came from ‘The Aristocrat of Harlem’ shaped a musical revolution that is cherished almost 100 years on. The only question is– who else did history forget? (We’ll keep trying to find out).