A few weeks ago, I fell in love with a movie called Shirkers. It felt like discovering a lost Wes Anderson movie. It felt like watching all the things I’d ever set out to portray here on Messy Nessy Chic– secret childhood drama, unappreciated beauty, deeply personal nostalgia, conspiracy, vulnerability, creativity– all perfectly wrapped up in this dreamlike alternate universe that is Sandi Tan’s filmmaking. Tan is the writer and director … of both films. You see, Shirkers (2018) is a documentary about finding another film, also called Shirkers, which she began making in 1989 with her friends and high school film teacher while growing up in Singapore. It was a beautiful and ambitious experiment in filmmaking; a cult classic that never was; because when shooting wrapped, her mysterious film teacher, whom Sandi had idolized, disappeared with all the footage, never to be heard from again…

As soon as I finished watching the film, I had to tell everyone about it. So I recommended it on Instagram, in our newsletter and pressured everyone around me to go look at this film I’d “found” on Netflix. But then, she found me; Sandi Tan, the creator of Shirkers. In fact, she’d found me a long time ago. “I’ve been bookmarking your pages for years”, Sandi wrote to me in all-capital letters. Those seven little words made my heart flutter. We exchanged mutual slobbery appreciation for each other’s work before she agreed to do an interview for Messy Nessy Chic. So here is the result of that kismet…

PS. If you haven’t yet seen the film, go and do that right now and meet me back here.

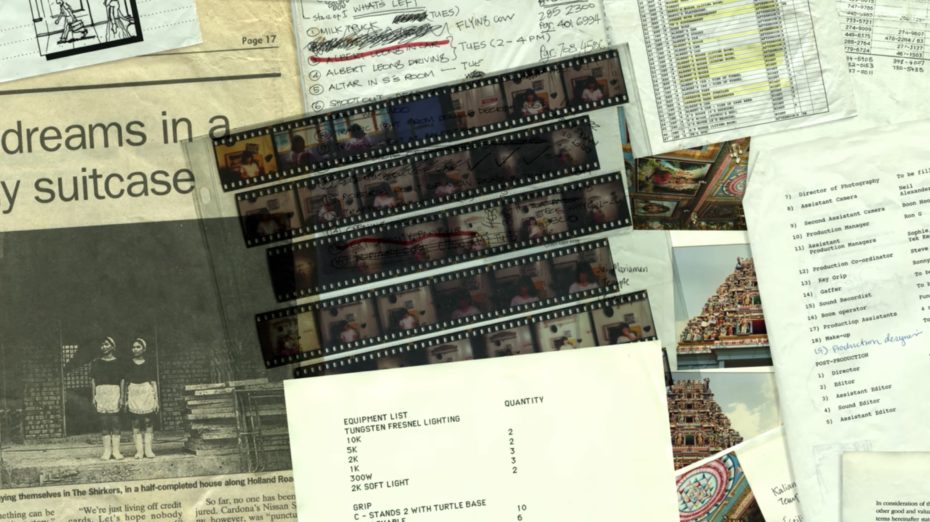

Stills from Shirkers 1992 © Shirkers Movie on Netflix

MNC: There’s a tone in your voice as a narrator that has a lot of sadness in it. Have you made peace with your loss? Are you even now glad this strange tragedy happened to you so the documentary could happen? I think what I’m trying to ask is– do you now think the documentary is the better outcome? (Or are you still pissed?)

I’ve made total peace with all of this– and though I’ve had my angry years and my ashamed years and my horrified years and the years that was a combination of all of those things, I now feel free of the toxicity that the “loss” introduced into my life. Time can be a very strange friend and I have recognized it to be also a bittersweet uroboros: without this loss of Shirkers 1992, they’d be no Shirkers 2018. And I believe Shirkers 1992 lives its best life within my current film.

Producer Sophie Siddique with Sandi Tan during the making of Shirkers, 1992

I don’t think I could fully account for my lost years nor do I ever dare indulge myself in going down the rabbit-hole of what-could-have-been, but making this film was a life-altering experience. A wise filmmaker friend of mine told me that he thought completing a film like Shirkers would change me “on a molecular level,” and I do believe he’s right. It’s like I’ve been whole again, singing this strange duet with my younger, forgotten self, and realizing that this person is still very much a part of me–and that she can continue to be. We shouldn’t have to shed layers as we grow up; we should be able to wear our many skins all at once. I think that’s the privilege of experience. You earn your layers– and you get to rebuild your heart.

Stills from Shirkers 1992 © Shirkers Movie on Netflix

When you were making the original Shirkers, what were your expectations for it once it was going to be finished? Sundance? We know from the doc that George Cardona alluded it could go to Cannes. Do you think it would have made it?

No! We had no expectations–the simple act of making the film back in those days was revolution enough. Nobody was making films there, not like we were: a band of fearless kids knocking on doors and sweet-talking old aunties and uncles into letting us shoot in their bedrooms, cafes, hallways, bowling alleys, supermarkets, front yards, backyards, fuelled by beauty and adventure and my dare to myself to make a film before I turned 21 (or perish).

The Lost Footage

MNC: Instead of a documentary, did you ever attempt or consider editing Shirkers as it was intended by your 18 year-old self, either with new sound & sound effects, or re-shot entirely? In this right circumstances, would you do it now? Or is it time to leave it at peace?

No, I did not because the story of how it came to be is so much more compelling than the reconstruction of the original Shirkers itself. The reassembled film might be a colorful oddity and an endearingly eccentric time capsule of a very specific, imaginary, curated Singapore (in the way Lynch’s and the Coen brothers’ America are not really America) and I definitely will consider reassembling it (with the aid of a volunteer squadron perhaps) someday.

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

It was a deliberate decision not to include any skyscrapers and aspects of 90s Singapore; even by 1992, Singapore was very much a steel-and-concrete city, not really the bucolic sleepy fictional Singapore you see in the 16mm footage. I wanted to capture my favorite alleyways and my favorite My Blue Heaven gate and my favorite mannequin shops–all those things I knew would evaporate before our very eyes because all the good, special things seemed to do that in Singapore because it is a city-state where most school campuses look like spaceships or inside-out bathrooms.

The mysterious Georges Cardona © Shirkers Movie on Netflix

Georges was a perfect collaborator for me because he, too, was obsessed with the great old buildings of Singapore and we’d break into abandoned mansions on weekends to imagine them in their original glory, and there’s an entire 16mm reel in the recovered footage which is made up of still shots of old buildings we found in the city: pink walls, green shutters, mosaic flooring. We loved all that stuff. Making the original Shirkers a road movie was an excuse to capture these faces and places before the little kids grew up and the older people died and the world I knew lost all of its magic. I always wanted to be an alchemist. This became the perfect opportunity.

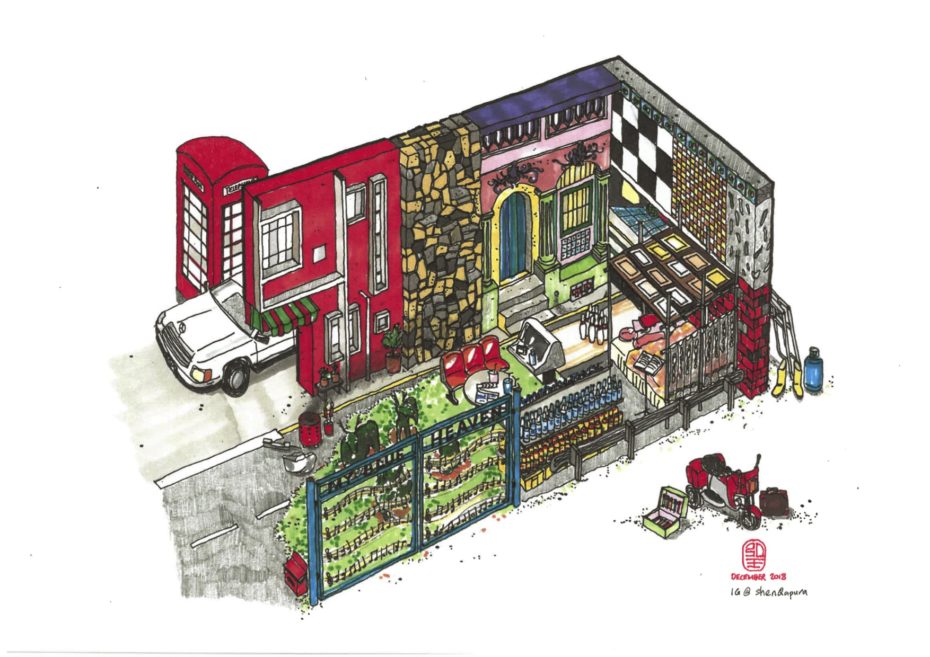

Fan artwork by shenQapura @shenq

By the way, I love that I’m not the only one to love this stuff. A new generation has come to be obsessed with the Shirkers locations too. I just found on Instagram yesterday this artwork by a fan of the film and it’s an impressively detailed composite drawing of various Shirkers locations done as a kind of imaginary diorama!

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

MNC: You put me on Cloud 9 when you said you’ve been bookmarking Messy Nessy Chic for years, but when you were a teenager, leading up to creating Shirkers– other than the movies, where and how do you find your creative fuel? (Or is the simple answer: child prodigy?!)

I don’t think I was a child prodigy, but I will say I was prodigiously unhappy because of my environment (including 99.1% of the humans therein) and knew that the best way out of that was to imagine my way out of boredom and depression. It was that or death. So I was never bored for a second. I played with dollhouses and Playmobil playsets until I was way too old (um, into my mid-teens), making up elaborate plot-lines for the multitude of characters that my baby cousins could not begin to follow. That was my hobby.

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

I read a lot about movies but because it was so hard to get a hold of them (especially old movies and foreign-language movies), I often imagined them from reading their synopses– my other hobby was memorizing cast and crew and year details from the Leonard Maltin film guide and film magazines like Sight and Sound, talk about sad! I also watched a lot of horrible TV and read a lot of Enid Blyton, VC Andrews, and also some Camus. I also absorbed the stories told by the older relatives around me. I observed a lot because I had no siblings and no parents. There was a lot of controlled insanity within my gothic extended household; it was the perfect unhappy environment for a budding artist or psychopath. (I think I am a bit of both.)

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

MNC: Do you think there’s too much “inspiration” at our disposal now with the internet to be truly original anymore? Do you feel the pressure to do something truly original as a filmmaker?

To the first question: Yes, perhaps. But I think inspiration often morphs into different forms in the brainwhorls of the viewer. So what seems like overload to one person can still be amazingly inspirational to someone who is glancing at the screen for a second and gleans a million new ideas because that particular shade of aquamarine hit the light in the top left corner of their phone a certain way. If you’re receptive to ideas, there’s no telling what will come from where, or from whom, and in what order. Second question: No, I don’t think like that. I just want to make good, compelling things… that don’t feel stale or make me sick to my stomach with regret/boredom/disgust.

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

MNC: As you know, we’re huge fans of Wes Anderson here– and having now discovered you and Shirkers, we think you’d make the ultimate dream team, but also, could be his female rival! Is that a place you think you might like to take your film career to now? (Not as his rival per say, but to that level? Are you looking now to pick up your career from where you left off as that 18 year-old filmmaker with a dream?)

That’s a wonderful compliment!! The soundtrack to The Royal Tenenbaums is on permanent rotation on my listening device. It dictates the cadences of my thinking life, often. That, and the scores for Under the Skin, There Will Be Blood and most of Douglas Sirk’s movies. I’m working on a bunch of very exciting film projects (which I cannot wait to talk about, but can’t just yet)– however none of them will be Wes Andersonian in look or spirit… with the exception of maybe one! But because my temperament is slightly different (I think), it will probably be a tad… nastier 🙂

MNC: What do you think are your obstacles now? Do you find yourself more afraid to dream as an adult? Or quite the opposite?

Nope! I’m less afraid. Because: 1) my old child-buccaneer self is now fused with my adult self– the self that is cognizant of what one needs to do in order to do what wants to do– and it should be a fun collaboration, 2) Computers! The internet! Possibilities have expanded exponentially!

Behind the scenes during the making of 1992

MNC: Is it possible for kids today to still make a movie like you did back then? Or do you think it’s even easier with Smartphones today?

It is possible for kids today to do anything they want! The movie may take a different form, and it’s totally correct for us to be unable to imagine what that form might be. (But they’ll figure it out. Kids always do! And we’ll be surprised!)

MNC: What are the three most important aspects of filmmaking to you?

Story, first off! I’m big on story.

Cinematography!

Editing!

Sound/Music!

(Psst! I found the Shirkers playlist on Spotify, which I’ve been listening to while piecing together our interview).

MNC: I loved the before & afters of Singapore you did in Shirkers– but are there still parts and people of Singapore that have the same magic you remember?

No, it’s all gone now. The food’s still good though.

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

What do the next six months look like for Sandi Tan?

OMG. The immediate week and a half is comically busy. But I’m used to insanity and not sleeping, so that’s fine. Once the madness winds down a bit, I’m hoping to get to work on the film projects I’ve had to put on hold while promoting Shirkers. I am so very much looking forward to this!!

© Shirkers Movie on Netflix

I’ve also got a huge pile of books to read (for work and for pleasure) including a new 1,000-page NYRB translation of Cain & Abel by one of my favorite authors, Gregor von Rezzori, The Kindness of Strangers by Salka Viertel (also from NYRB), and the many books written and drawn by friends, including graphic novels by Dash Shaw, Connor Willumsen and Tomer Hanuka, and Saskia Vogel’s upcoming novel Permission and Mark Doten’s upcoming unclassifiable Trump Sky Alpha. And various biographies I’ve started reading but put down and forgot about because when you’re making a film, it devours you whole, and your brain kinda goes a little… shirky.

Sandi Tan is on Instagram. Shirkers has been numerous awards since it’s release, starting with the Sundance World Cinema Documentary Directing Award. And if it isn’t nominated for an Oscar, I’m gonna be pissed. Shirkers is available for streaming on Netflix now.