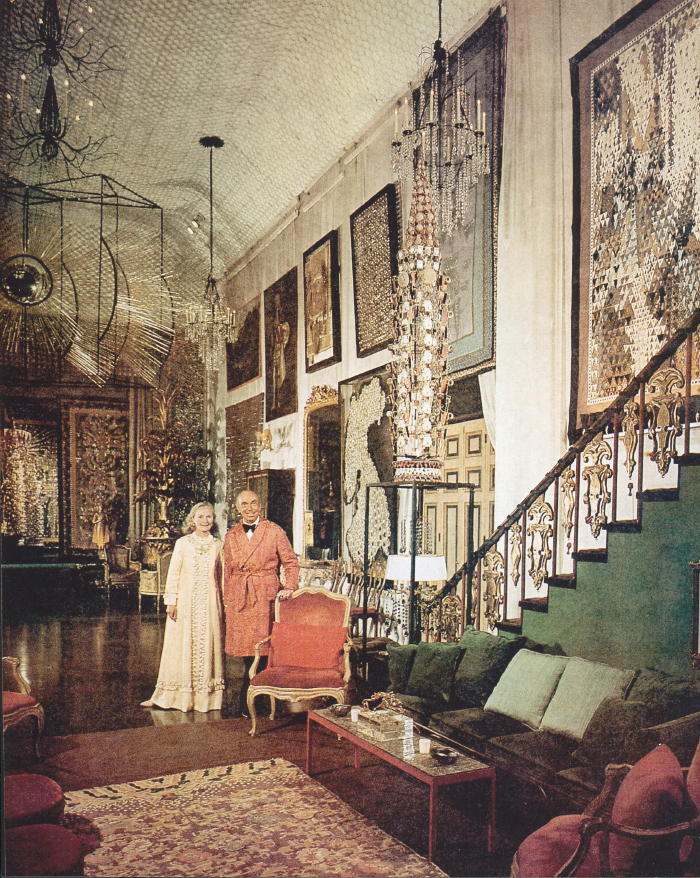

Tony Duquette and his wife, Beegle. Tony Duquette

He was the man with the thriftiest of Midas touches, and the only decorator who could spend $999 at a 99-cent store thanks to one mantra, seek “beauty, not luxury.” Tony Duquette was a Renaissance man of film, theatre, interior and jewellery design in Hollywood– if you name it, he probably built it and dipped it in gold for the world’s grandest stages and socialites. But the real reason Duquette’s work speaks to us today isn’t because he was the only American to exhibit solo at the Louvre, or decorate Paris’ Palais de Bourbon and Venice’s Palazzo Brandolini (ok, maybe a little). It’s because Duquette’s glamour was inclusive, clever, and weird; he would build pagodas out of old air force landing strips, and cover a ceiling in styrofoam grapefruit crates. He’d design an alligator costume for the San Francisco ballet, but make it cheetah-print to lighten things up. Today we’re retracing the silver threads of his story and fantastic creations, from Beverly Hills to the mountains of Malibu, to find a bit of embellishing inspiration for ourselves…

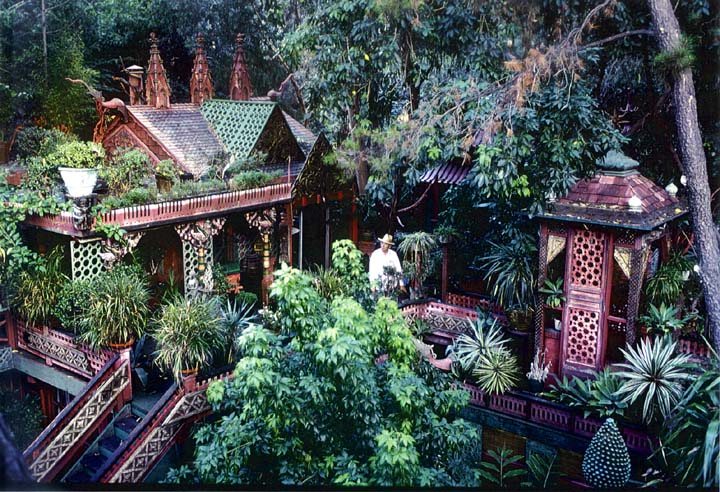

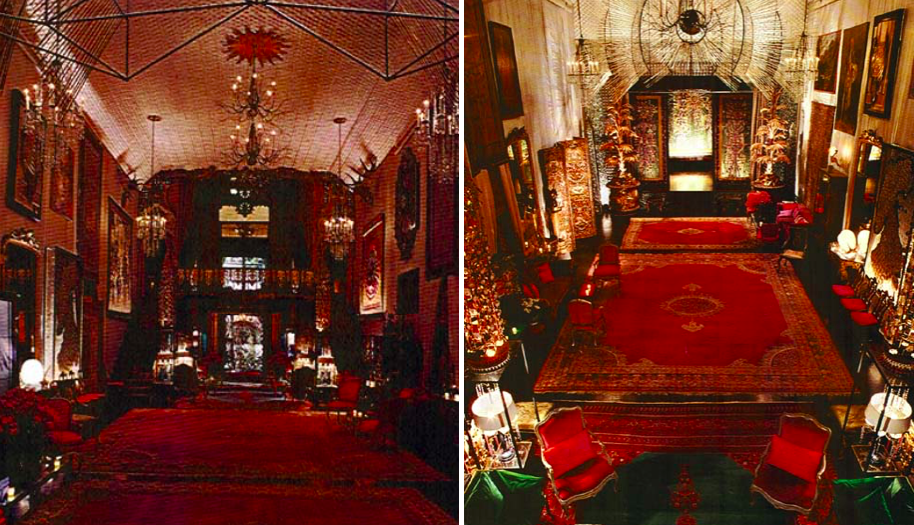

Duquette and his wife bought the Beverly Hills home you see above, with Duquette at its centre, for $1,500 in 1949 and crowned it Dawnridge. “It’s a small house but it’s set on a very large piece of land. 5.5 lots” says Hutton Wilkinson, Duquette’s protege and business partner, in an interview with Open House NYC in 2016. For a bit of price perspective, consider that the actress “Sharon Stone paid 3.5 million for half of a lot” in the same area.

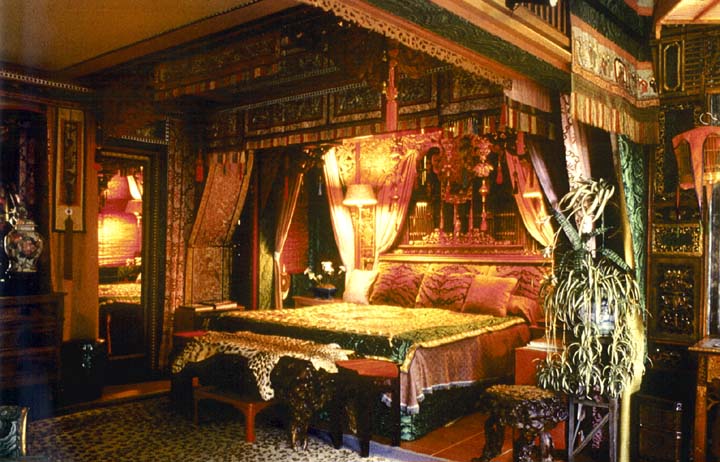

Today, LA is congested with Italianite mini-mansions, tacky buildings squeezed into bungalow-sized lots of the “Golden Triangle” (Bel Air, Brentwood, and Beverly Hills) and beyond. Now Duquette’s property is a whopping 5 1/2 lots, but the house is its little luxurious pulse, the glittering speck of a one-man kingdom where fountains and koi ponds gargle amongst old MGM Studios frog obelisks. It’s a jewellery box in the jungle.

Duquette. Wikipedia.

The majority of the plants on the terrace of his Beverly Hills home are actually potted, explains Wilkinson, who now runs Duquette’s estate and brand. Most were salvaged from back alleys after being thrown out of rich gardens in Beverly Hills, and all the succulents were saved from the Dodger Stadium’s lot before construction began in the 1960s. A few years later, Tony and his wife bought another space to expand his growing studio needs. It was in a bad part of town, and their dining room shared a concrete wall with a liquor store, but they didn’t care (they actually painted a mural of Venice over it). It was also the home of that infamous styrofoam ceiling:

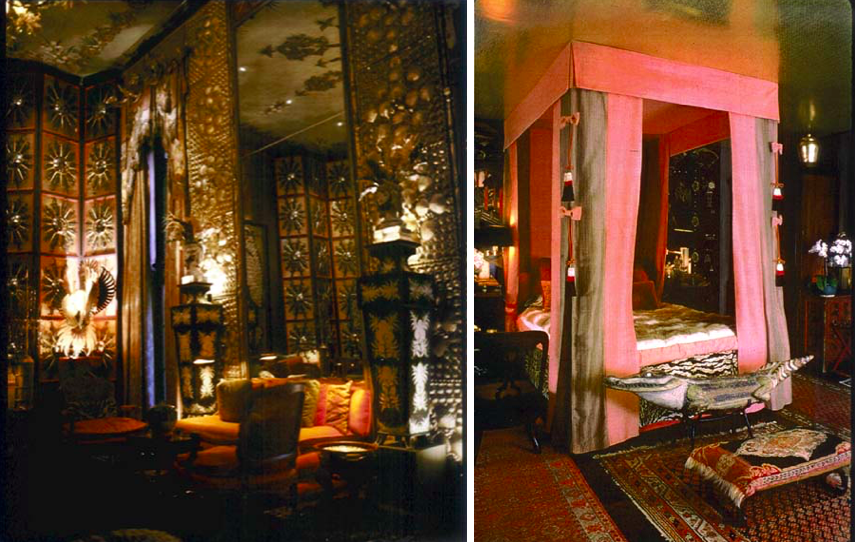

Tony’s studio. The ceiling is covered in pink styrofoam grapefruit crates. Tony Duquette.

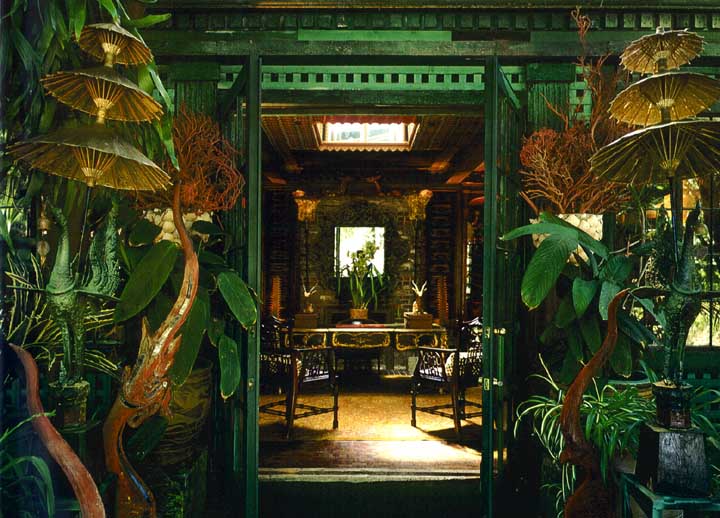

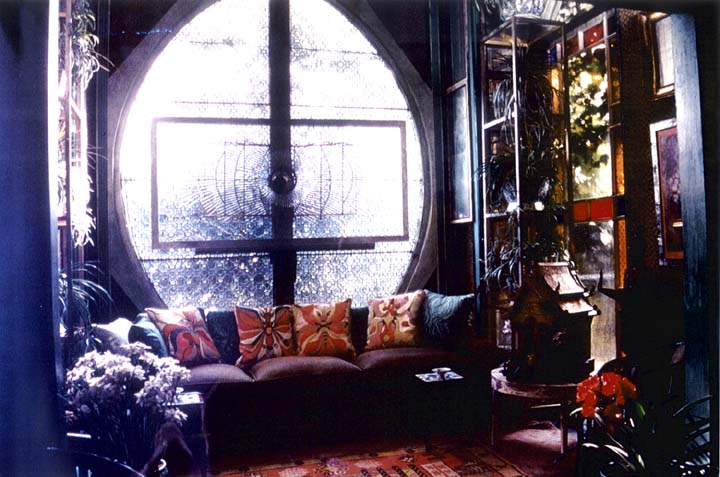

Below is “The Treehouse Room” at his studio, and according to Duquette’s website “the large egg shaped leaded glass window was created by Duquette using two overdoors from the historic Metropolitan Opera House in New York City”:

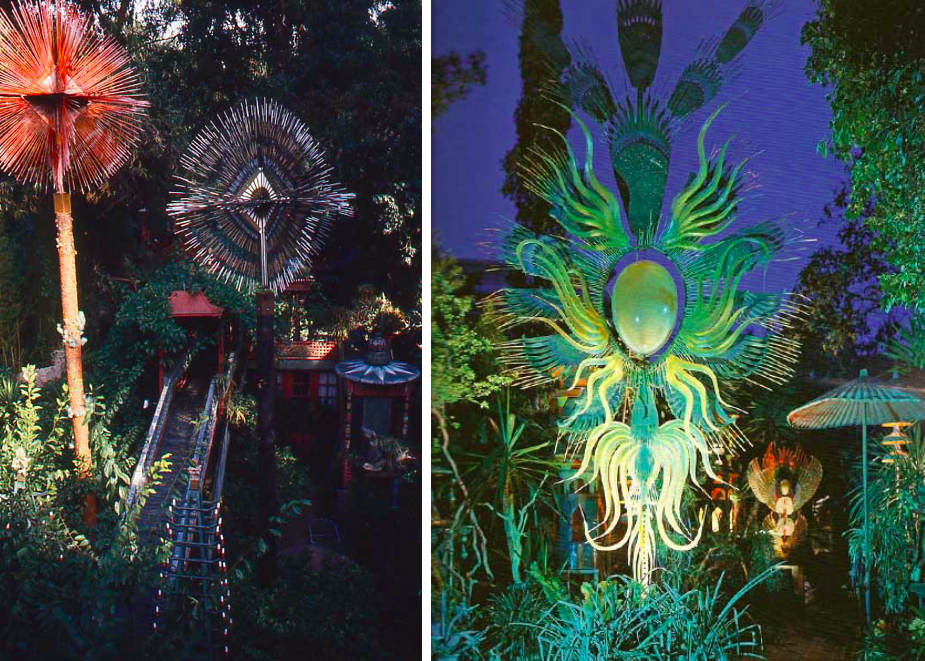

The magnum opus of his decorating feats was arguably his Malibu estate, which he and his wife bought in the 1950s and called “the Empire” because it encompassed 21 structures with their own themes, from the “Frogmore” house to the “Rose Parade” room, a narrow structure lined plants and Victorian antiques, all in front of a sacred Native American rock range called “Boney Mountain”. Tragically, every last bit of it burned to the ground in wildfire in the 1990s.

With Greta Garbo in their Malibu Ranch.

Now the weight of Duquette’s glitz is enough to make him seem like some sultan reincarnate, maybe a quirky Vanderbilt, but that was far from the case. In a lecture for the Hilllwood Museum in 2017, Wilkinson explained that Duquette’s self-made dandyism ran in his veins, and any high society connections he had, he made from the ground up. His mother was a bohemian cellist from London who knew how to pinch a penny, and had moved with her own freewheeling parents to Canada, eccentricities in-tow, to spend more time in nature. They eventually moved West to California when their log cabin was “burned out by [Native Americans]” for the third time, paying their way across the states as a makeshift string quartet band. Once she arrived in San Francisco, she met her husband, and Tony was born in 1914. When he made an Art Deco-inspired “Marco Polo” puppet show at age 10, his destiny became pretty clear…

Tony Duquette’s Marco Polo puppet show. Hutton Wilkinson Hillwood Museum Lecture.

Tony studied the Arts at university on a scholarship, grew up in San Francisco in the winters, and spent summers in the Midwest where his father (originally from Michigan) owned some local businesses. When the Great Depression saw their collapse, 18-year-old Tony went to Los Angeles to inch his way into the design community, and provide for his family. He started out working at department stores and the chic American designer, Adrian.

Robinsons Dept. Store. Tony Duquette.

His merchandising work was simply anything but commercial, and created the kind of extravagance Americans were craving. With war ravaging Europe, affluent Americans could no longer dip out to Paris for the glamour of couture season. So Duquette brought the glamour to them, and everyone else in LA…

An Adrian display by Duquette. Tony Duquette.

Might we mention, he made the most beautiful toilet paper ad we’ve ever seen:

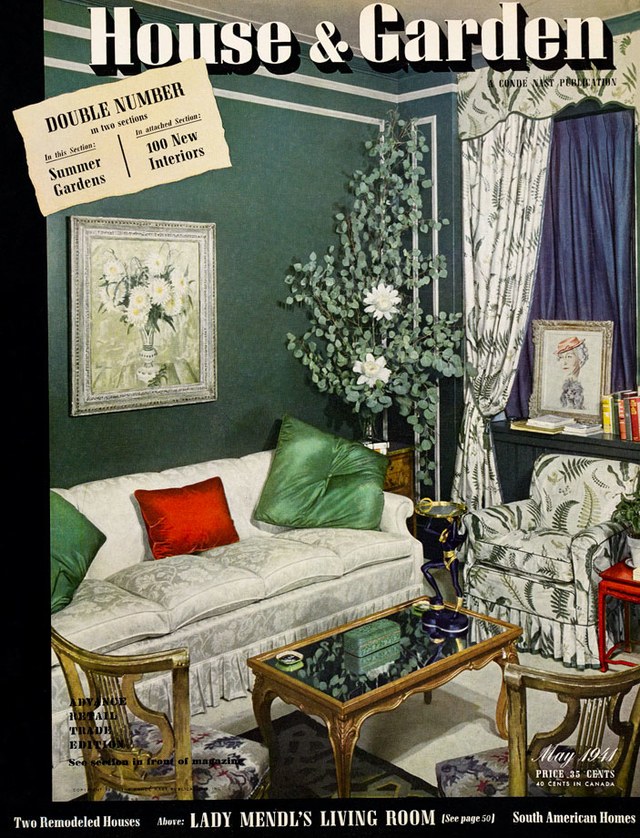

In addition to working for Adrian, who had done costumes for some of the biggest Hollywood studios, Duquette was actively sending designers his own little shoebox creations to get noticed, and pretty soon he started to make a real name for himself. But it was Elsie de Wolfe, aka “Lady Mendl”, who gave him ultimate street cred when he decorated her home in the States. The American socialite, actress and decorator fled her home in Versailles during the Nazi occupation of Paris, and decided Tony was the only one fit to make her a new one in LA, even though, as she said, the entire house cost less than one object on her dining room table in France…

As for the woman who captured Duquette’s heart? Enter Elizabeth “Beegle” Johnstone, who was Duquette’s best friend’s sister. Beegle was a knock-out, and a painter with a brain on the same eccentric wavelength as Tony:

Tony and Beegle. Tony Duquette.

One night, on the way to a party at Elsie de Wolfe’s, Beegle plucked ivy from the yard to embellish her outfit to the amazement of Man Ray, who told her, “Don’t move, I’ve got to photograph you just the way you look this minute.”

Beegle by Man Ray.

Tony and Beegle were married in 1949 stars like Greta Garbo, Fred Astaire and Vincente Minnelli in attendance, and Mary Pickford as maid of honour. They made a perfectly curious pair.

At the Dawnridge Housewarming Party. Tony Duquette.

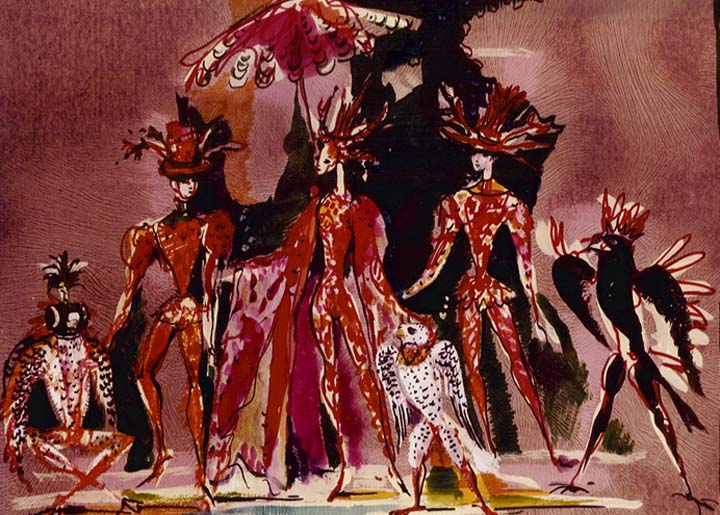

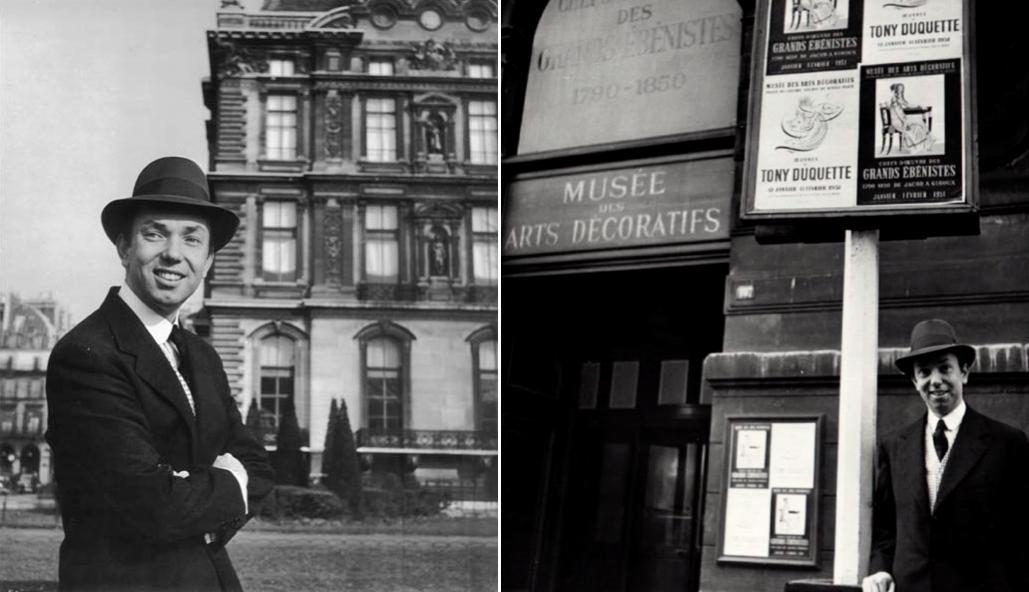

A year later, Tony got a call to do an exhibit at the Louvre to represent the decorative arts of the mid-twentieth century. “It was a strange choice because he was doing neo-Baroque decoration,” says Wilkinson, “not the chrome and black of Charles and Ray Eames. It was an exhibition of watercolour, costumes, set and jewellery.” Here’s a sprinkling of his movie and theatre creations…

Camelot costume design, for which he won a Tony Award. Tony Duquette.

The Magic Flute. Tony Duquette.

Kismet, 1955 (left), Lovely to Look At, 1952 (right). Tony Duquette.

For the 1955 MGM movie “Kismet”. Tony Duquette.

“Kismet.” Tony Duquette.

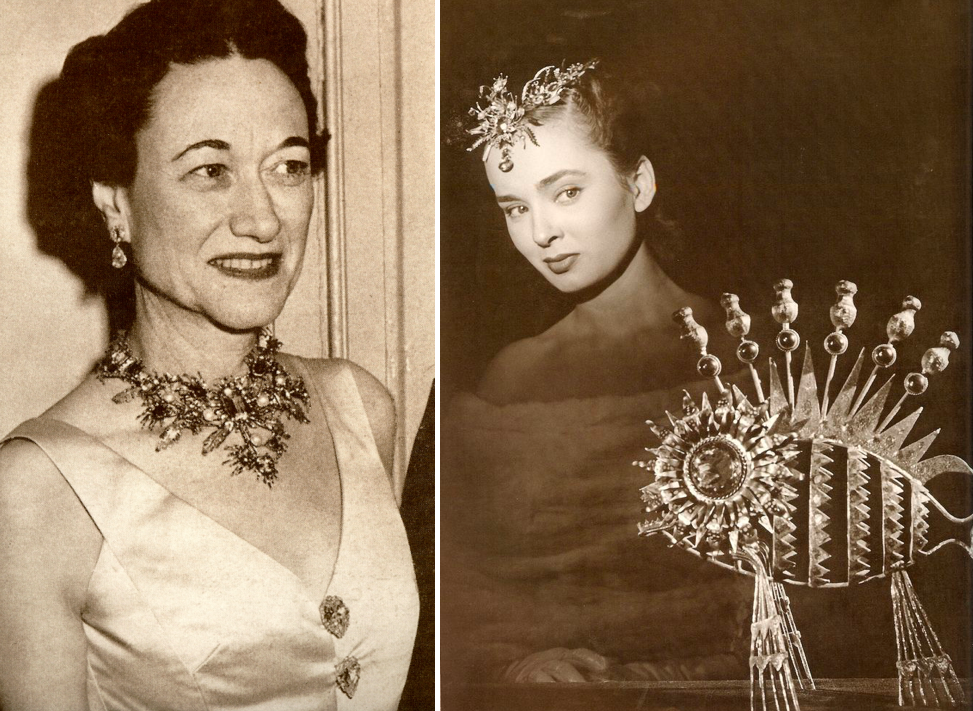

As fate would have it, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor happened to be at the exhibit and were dazzled by Duquette’s work. They commissioned a necklace for Wallis (below, left) that she wore the entire season, and whose popularity helped solidify his role as a jewellery designer as well:

The Duchess of Windsor (left) and actress Anne Blythe with another Duquette creation.

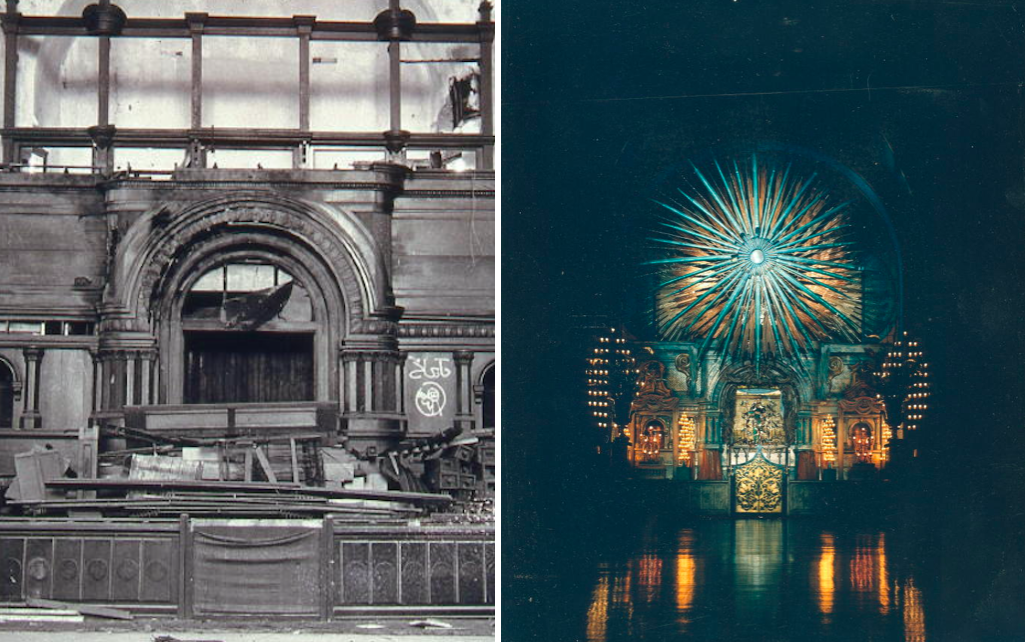

By the 1980s, Duquette was a living legend whose pieces graced numerous international museums, and whose talents touched not only the Hollywood elite, but extended to a number of public works. He personally bought and transformed an abandoned and vandalised synagogue in San Francisco, even though it would fall victim to a fire in 1989.

St. Francis Synagogue revamped by Duquette. Tony Duquette.

He lined the entry with his signature “California sunburst” designs, and crushed abalone, which along with green malachite was probably one of his favourite materials; he used to say that if there was only one abalone in existence on earth, wars would’ve been fought over it…

We’ll leave you with one of Duquette’s last grand masterpieces, a towering sculpture he called, “Queen of the Angels” made for the bicentennial of his beloved Los Angeles. It was, “a gift for the city to celebrate its poetic and evocative name” in the form of a towering archangel. Duquette saw it as a unifying symbol, explaining that Catholic, Jewish, Islamic, Buddhist, and Hindu faiths all “believed in angels with powers over the elements, beasts, music and death.

The installation was made with the help of “150 volunteers from all economic backgrounds”, and stretched up the 80-ft ceiling as the angel’s face changed colour electronically. Hidden speakers played a poem commissioned by Ray Bradbury and recited by Charlton Heston, and music trickled in by Garth Hudson. It was a runaway success, garnering more visitors than even the Getty on a weekly basis….until it also burned down. Now, even in California, becoming thrice a fire victim is pretty remarkable. Was Duquette’s work insanely flammable? Is there some mystery arsonist out there who really hated gold-leaf?

Duquette (left) and Wilkinson.

If anything, Duquette could handle the heat, as every new project he undertook became more surprising and sparkling than the next. Wilkinson remains a loving and talented guardian of his estate, and the Duquette brand and creations, new and old, are still very much alive. Learn more on the brand’s site, and whip out your own hot glue gun this weekend…