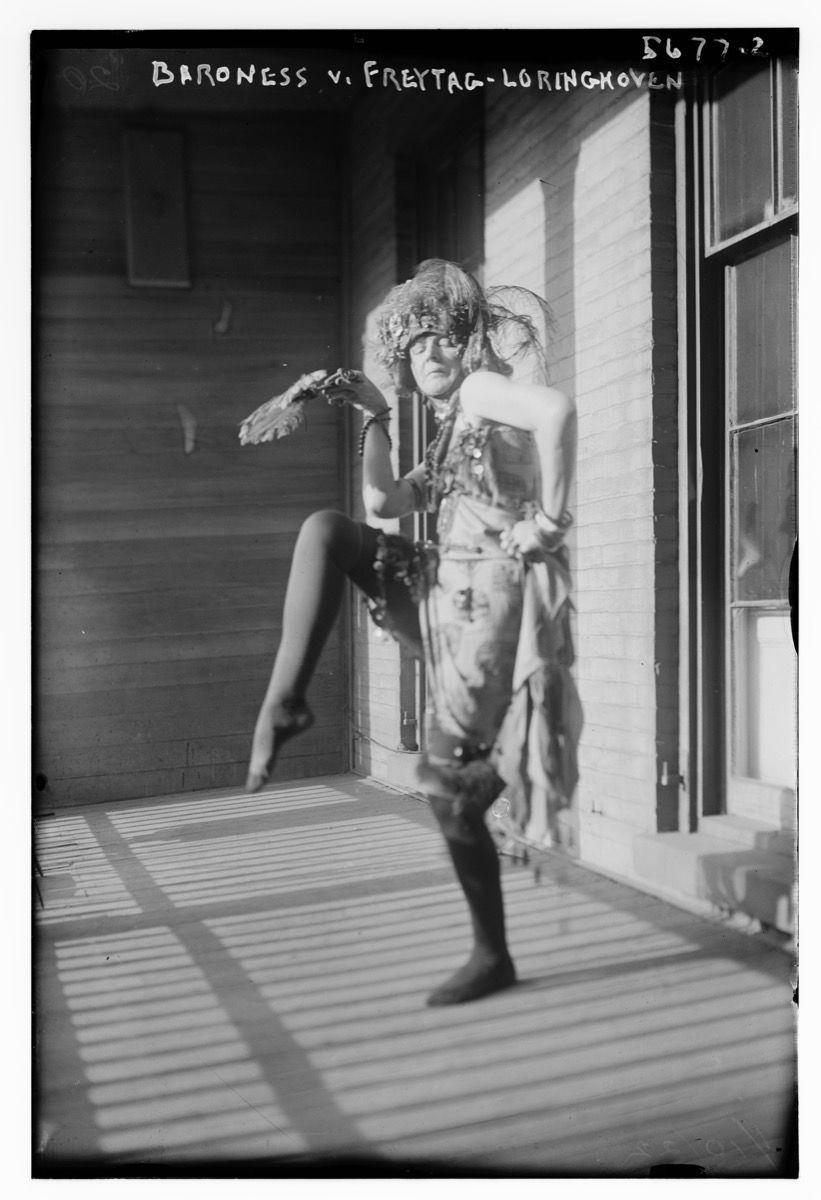

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven had a life as rich as her name was long. She became the belle of New York’s bohemian scene in the early 1900s, donning feather crowns and bras made of tomato cans, making incredible art and befriending cutting-edge Dadaists like Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. Then, she kind of faded into history as the Zelda Fitzgerald of the Dada scene; the text books were content to let an untimely death and wild persona eclipse her revolutionary place in the art world. You see, Elsa was not only doing Dada before Dada began, but she was the real brains behind what is largely considered to be the 20th century’s greatest artwork: Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 urinal sculpture. So how did her legacy spiral out of control, and into near oblivion?

First, a little crash-course in “Dada”. The creative movement that blossomed in Europe around 1915, and was led by Duchamp, Max Ernst, Hans Richter — honestly, the list could go on to include Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, and others, because Dada was one big ‘ole launching pad for avante-garde artists into the new century. They used found and banal objects, from bottle racks to irons, in “readymade” art pieces, works that tapped into existential, post-WWI disillusionment by throwing together bicycle wheels and metronomes to declare a new era of art. One that was ready to let turn things upside down, and let loose.

Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, one of the birthplaces of Dada.

Claude McRay (i.e., McKay) and Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, before 1928. Library of Congress via Artsy

Elsa was the kind of woman who made her own luck, so she fit in seamlessly with the Dada clique. Born in Germany in 1874, she studied art and flew the coop to do vaudeville in Berlin, making more and more of a name of herself amongst creative circles for her poetry and sculpture. Her love life was a bit of a tap-dance: first she married an architect named August, who she then divorced for a French poet, Felix, who she helped stage a suicide to escape his existing marriage and flee with her to America. It worked out great, until he left her for a cattle ranch.

So Elsa found her way to New York City, where she fell in love and married a German baron named Leopold. But they were far from living the luxurious, expatriate life in the Upper East Side. He was waiting tables, and Elsa was modelling for artists like Man Ray, while doing her own performance and assemblage art, and working in a cigarette factory. When their marriage ended, she had cemented her place as the wild baroness of Greenwich Village. “[She] became a downtown Manhattan legend,” explained Artsy’s Vanessa Thill in 2018, “known as much for her dazzling costumes and aggressive seduction techniques as for her visceral sculptures and witty poetry.” She had an enchantingly mad studio on 14th street, and published her poetry alongside James’ Joyce’s Ulysess; she collaborated frequently with Djuna Barnes (her biographer), and began blurring the lines between performance art, and her own life…

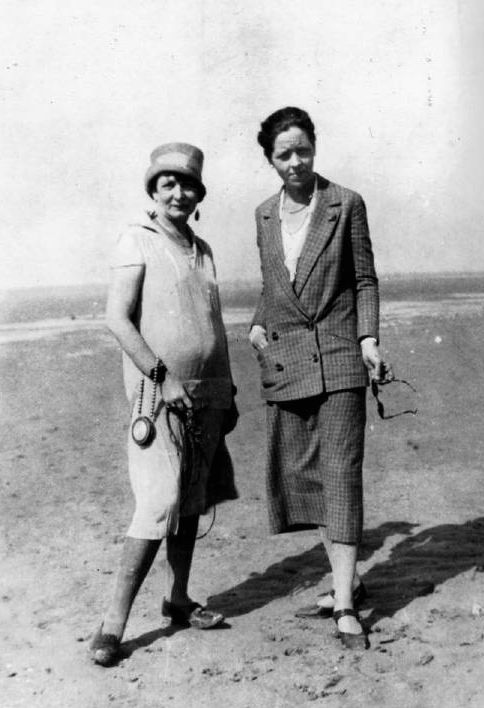

Elsa with Djuna Barnes, 1926.

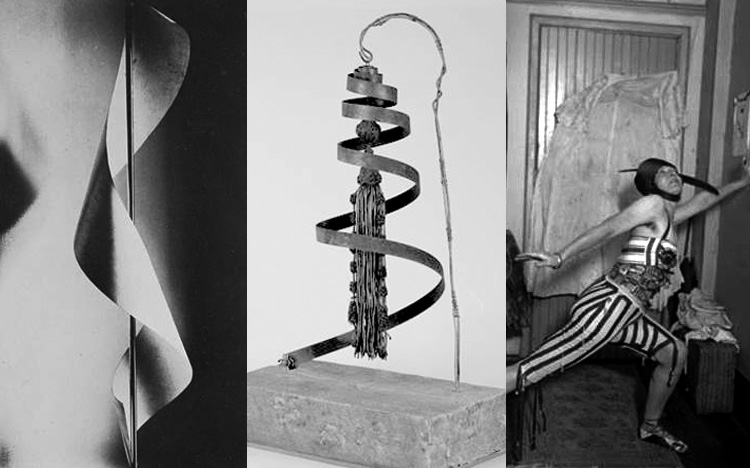

According to art critic Holland Cotter, “She developed a crush on Marcel Duchamp, who responded with passive evasion.” As the story goes, she took a news clipping about the French-American artist and rubbed it all over her body while saying, “Marcel, Marcel, I love you like Hell, Marcel” in a piece of performance art. Sparks didn’t fly for Duchamp, but he did declare her a force to be reckoned with, calling her simply “the Future.” She was a hot, glittering mess that spilled onto the streets of Manhattan nightly, drinking into the eve with her fellow artists and often getting arrested for public nudity not only for mere fanfare, but as her friend Emily Coleman later wrote, because “[she was] a woman genius, alone in the world, frantic.” That her art pieces should be just as eclectic, from the fleeting performance stunts to the found-object assemblages, was natural. Sadly, there are few that still exist today:

By the 1920s, Elsa wasn’t doing so good. Her lifestyle had started catching up with her mental health, and she spent all of her money on alcohol and new pets for her tiny apartment. And while Dada was fun, it was kind of a boys’ club, and what contributions were seriously acknowledged were mostly thanks to other women, writes Cotter, who says that it was Djuna and the female editors of The Little Review who published her work, and stood up for her time and time again.

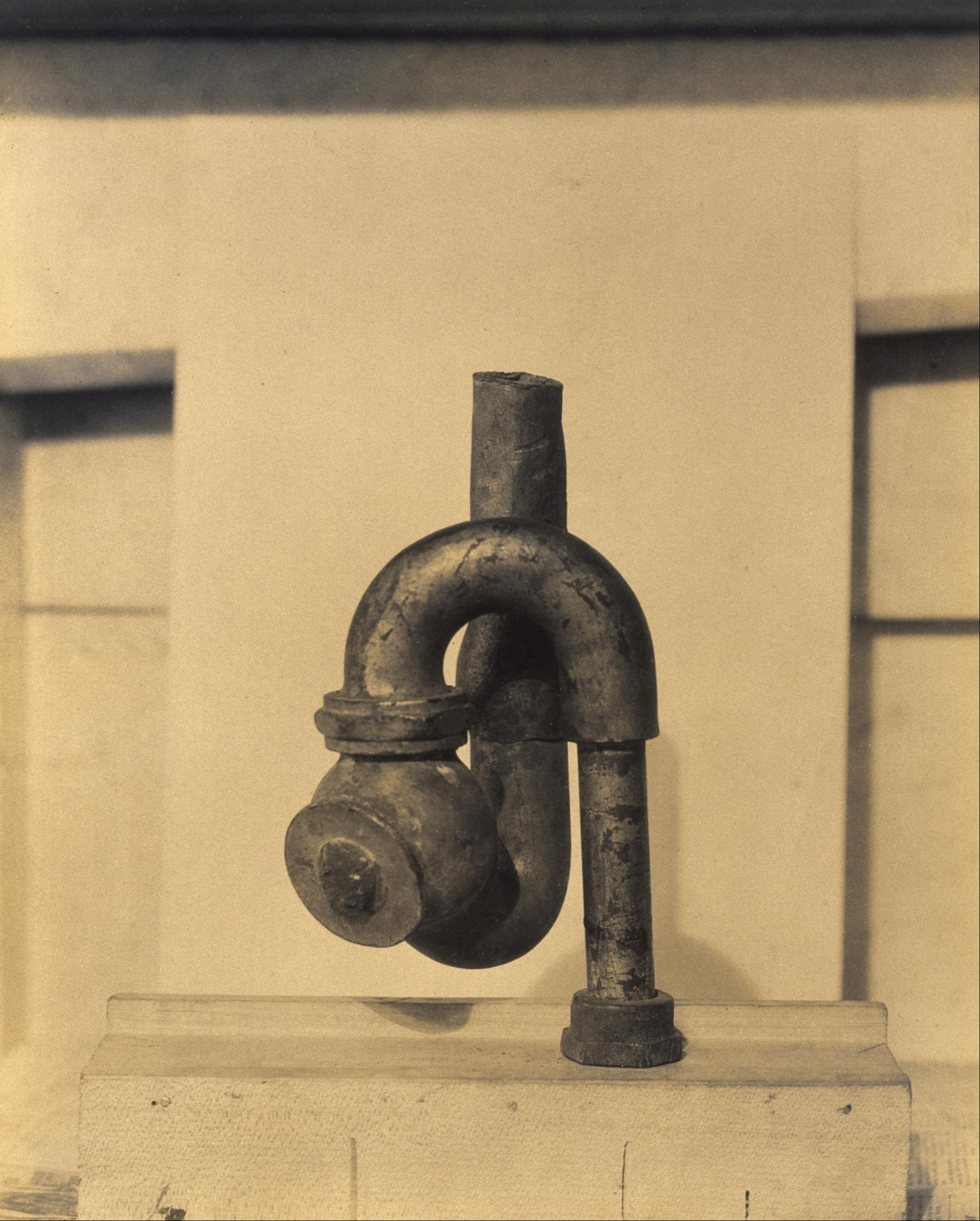

“God” 1917

And while it’s inspiring to have a no-holds barred, “self-as-creation” take on art, it meant a lot of confusion around what a finished Baroness work was. Consider this “readymade” iron pipe sculpture (above), titled, “God,” that was wrongly credited to another artist, Morton Shamberg. Today, the piece is believed to be a collaboration between Shamberg and Elsa, or a full-blown Baroness work itself. Which brings us to the big drama du jour…

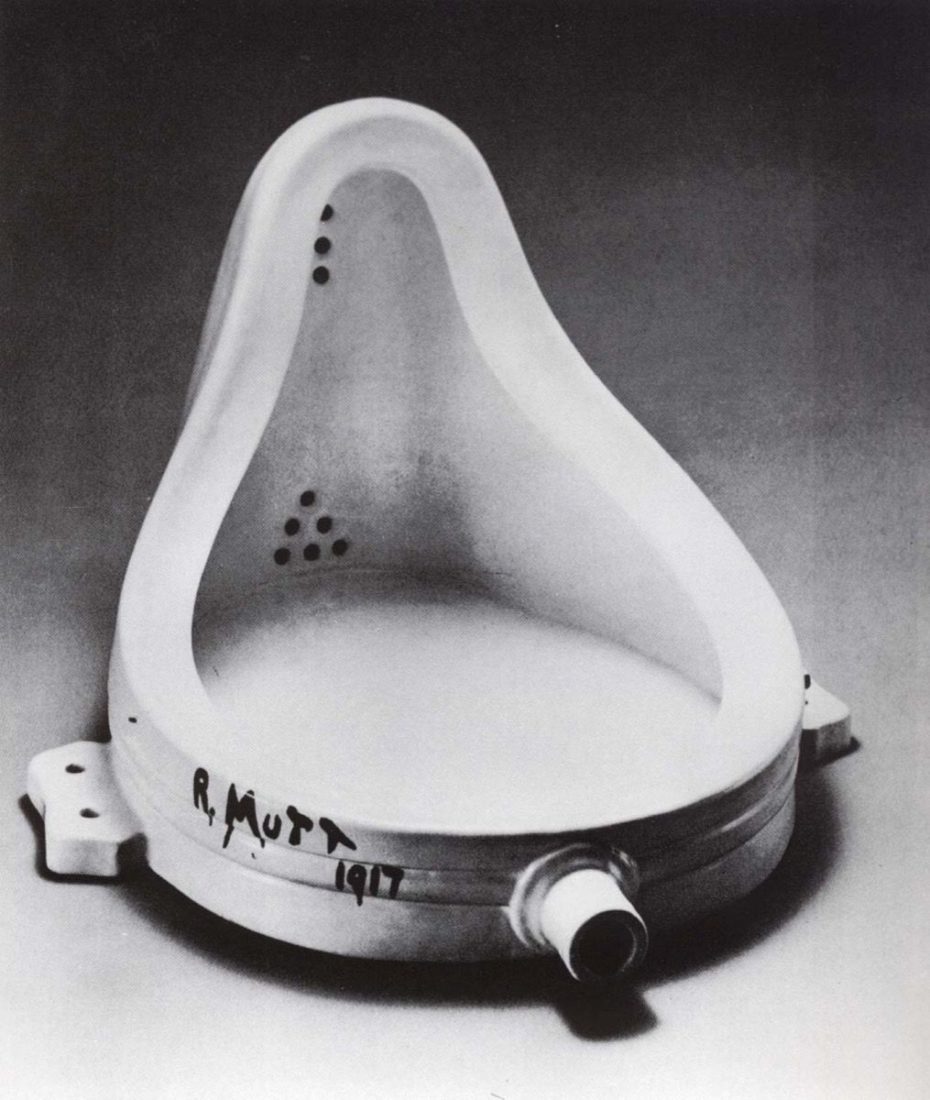

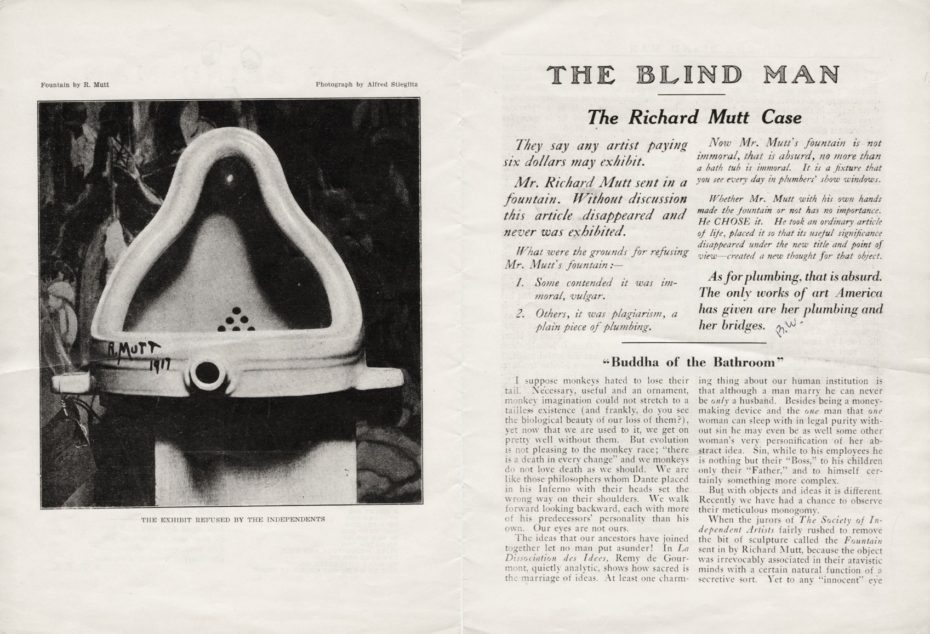

The Fountain

In 1917, Duchamp presented his infamous urinal sculpture, “Fountain,” for consideration by the Society of Independent Artists in New York under the name, “Richard Mutt.” The scandal it created was earth-shattering, and has long been considered a kind of metaphorical ribbon cutting into a brave new world of creative expression. “An object should express ideas; art should contain emotions,” wrote art critic Jerry Saltz about the piece for Vulture in 2018, “[They] should be easy to understand — complex or not…”Fountain” is an aesthetic equivalent of the Word made flesh, an object that is also an idea. Today it is called the most influential artwork of the 20th century.”

For over 100 years, “Fountain” remained a subversive beacon in Duchamp’s name. Then, in 2002, literary art historian Irene Gammel took a second glance at a letter Duchamp wrote to his sister, Suzette, in 1917:

“One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym Richard Mutt sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture. It was not at all indecent—no reason for refusing it. The committee has decided to refuse to show this thing.” – Marcel Duchamp

Now, the letter seems explicit enough. Amongst Duchamp’s friends, Elsa was the one who’d pioneered readymade works. She was also living in Philadelphia, precisely where the papers said the “Richard Mutt” who’d submitted the abominable sculpture was based. At the time, Duchamp also claimed he bought the urinal from a plumbing store on 5th Avenue, but historians never found the model in its catalogue.

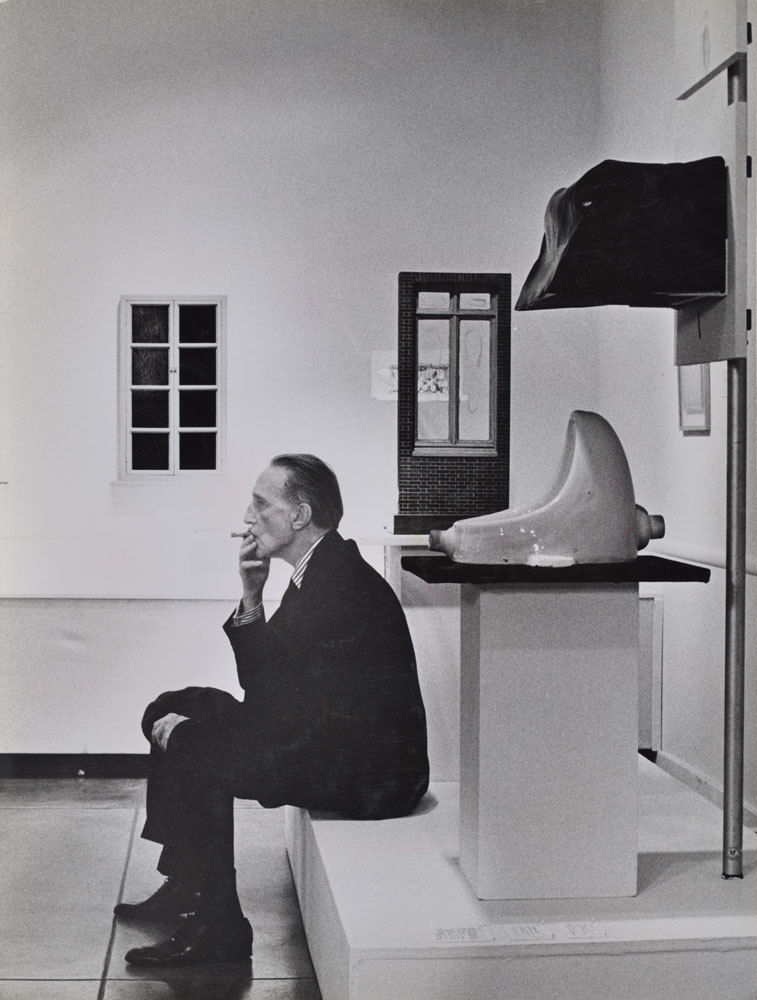

Duchamp by “Fountain”

Perhaps if Elsa had lived longer, she would’ve spoken up about the true nature of the exchange; was Duchamp covering for her in submitting it? Was he stealing her work? Was it a collaboration? Tragically, by 1927, Elsa was found dead from a gas leak in her Paris apartment, and as early as the 1950s the piece was inextricably linked to Duchamp…

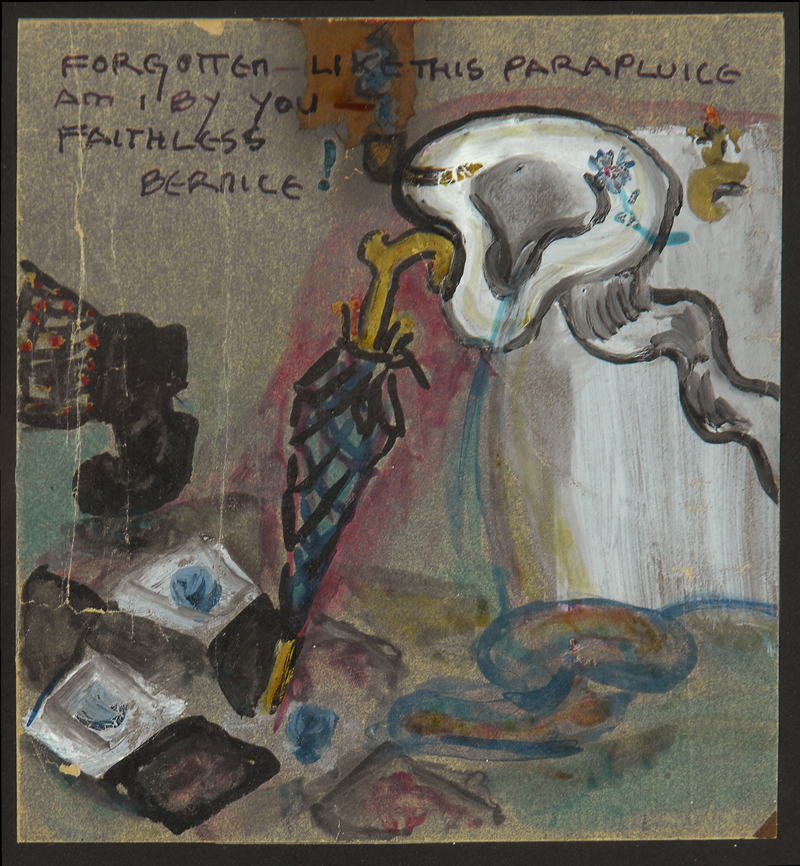

There is one last clue. This time, having to do not only with Duchamp but a photographer named Berenice Abbot, a tornado of a woman, and a talented photographer who became good friends with Elsa. Today, Abbot is regarded as a key American photographer of in-between war periods, capturing real life on New York’s Skid Row for a Federal Art Project, titled Changing New York (1935). When her male counterparts told her that “nice girls” shouldn’t head to that part of town, she simply replied, “I’m not a nice girl. I’m a photographer. I go anywhere.” In other words, the perfect girl for Elsa, who wrote a dedication to Berenice on her final artwork: “Forgotten– like this parapluie (umberella) am I by you — faithless Berenice!”

While historians can’t confirm a romantic relationship between the two, Elsa never conformed to a strict gender or sexual binary preference. One thing is certain: Berenice broke her heart. What’s more, the nail in the coffin is the depiction of a flowing urinal on the right, which pours onto the forgotten umbrella. Even for enigmatic Dada, this is one piece that rings pretty clear…

Today, the true scope of Elsa’s oeuvre remains fuzzy, lost, sometimes simply unknown. But as time goes on, more and more of her works are being reconsidered, discovered, and placed into major museums like the MoMA, or Whitney. And if you’d like to go raise a glass to her legacy in person, she’s buried at Paris’ Pere Lachaise Cemetery.