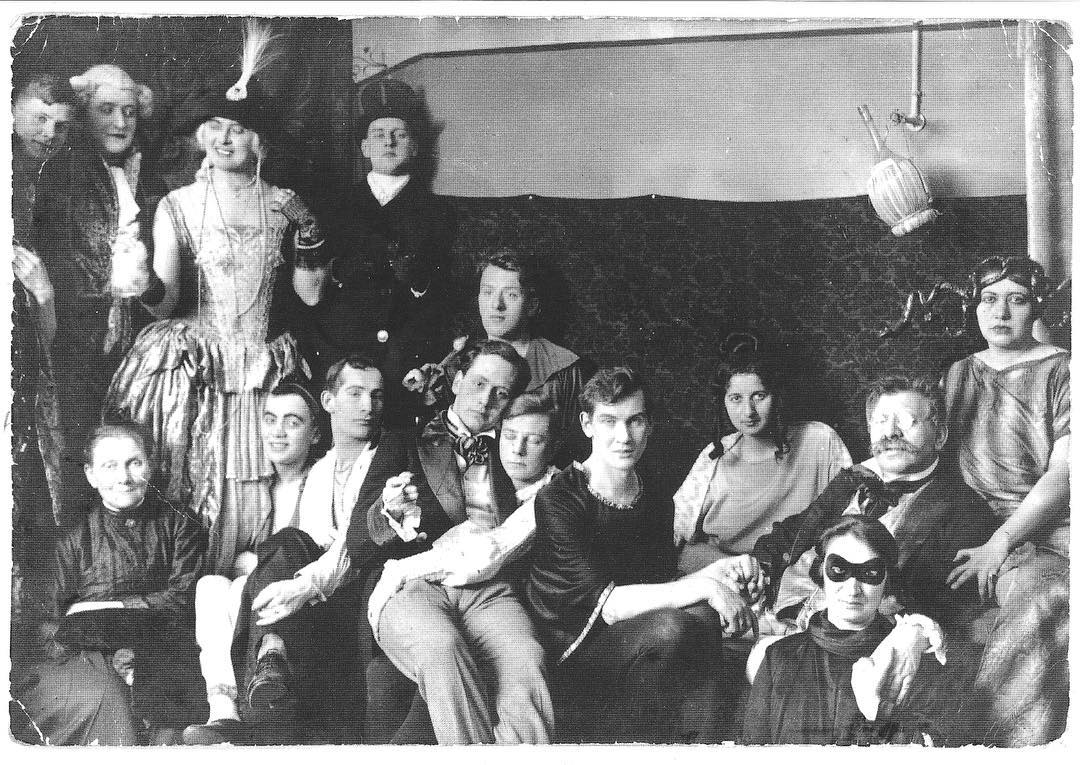

They called him “the Einstein of Sex”. The German doctor who went (quite literally) where no other had gone before in his research, founding the massive Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, or Sexology, just before the Nazis eclipsed bohemian Berlin and its costumed, sexually liberated splendour. His name was Magnus Hirschfeld (see the dude with the glasses and moustache above?), and “he was a huge deal in his day, even though he’s not very well known [now],” explained Robert Beachy in a 2017 Undiscovered podcast, which explains why he was so high-up on Hitler’s hit-list. Today, we’re retracing the highs and lows of his career, from a, eherm, “self-pleasure bicycle” to his revolutionary strides in gender reassignment surgery…

Going into medicine was a no-brainer for Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, who was one in a large Jewish family of doctors. By the 1890s, he was running his own practice. Then, a mysterious letter from a patient– a young soldier slated to wed a woman– changed his life.

“Please could you educate the public on the bad fate of people like me,” it read, “who are not fit for marriage. Please tell the public everything about us.” It was both a coming-out letter and a suicide note to Magnus, who was himself gay, but not “out,” because he knew a declaration of his sexuality would ostracise him from the medical community.

Still, the letter sparked a fire in Magnus. He packed up his bags and moved to the big city of Berlin to change folks’ perception of homosexuality “with science” (yeah…we’ll unpack that in a minute). When his family protested, he clapped back, “What are you saying: that cholera brings you more joy than sexuality?” If there were anyone with the right attitude and sass to start the fight for equality, it was Magnus.

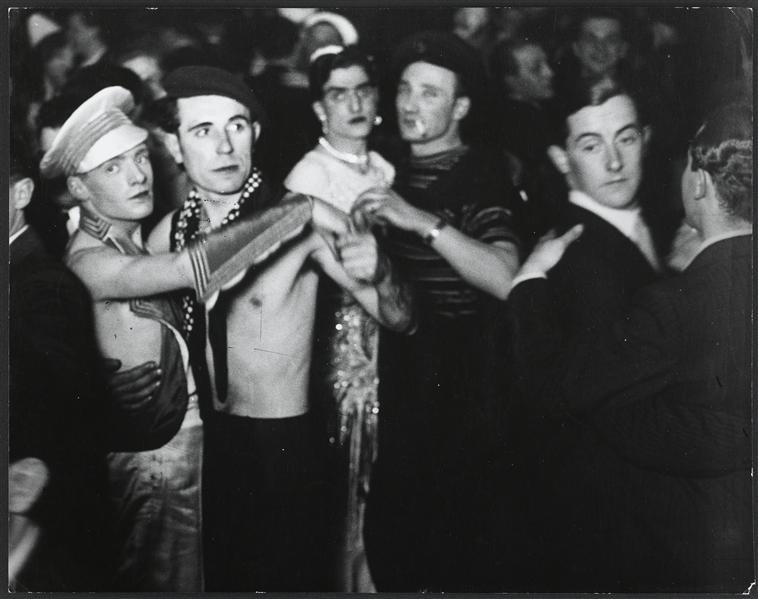

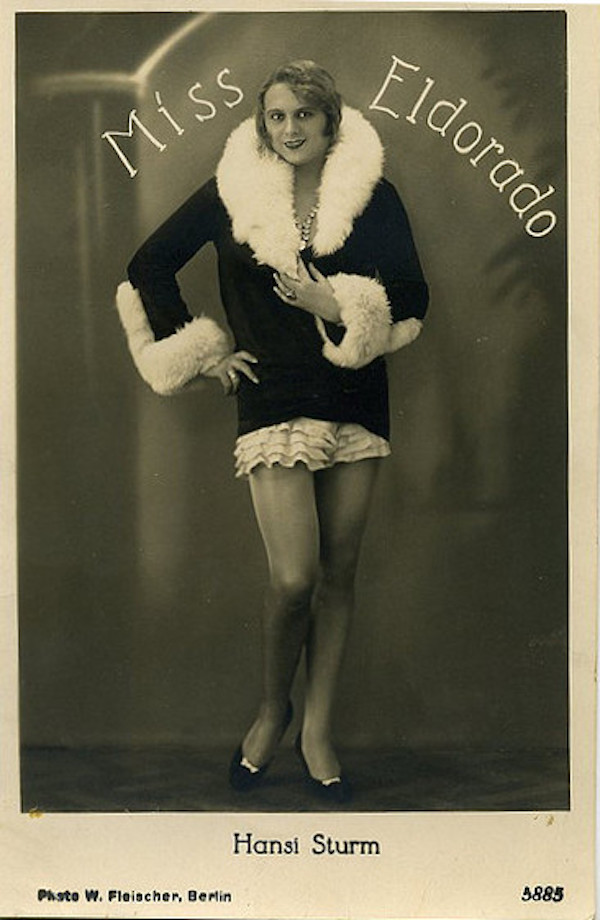

Why Berlin? Much like Paris at the time, it was not only intellectually stimulating, but fun. You could head to the El Dorado Cabaret, and drink in the cross-dressing drag brother duo, the Rocky Twins, or head to an All-Lesbian chess match. There was even a even an LGBTQ anthem of sorts called Das lila Lied, or ‘The Lavender Song’, whose lyrics chanted, “We are just different from the others/we are all children of a different kind of world/we only love lavender night…”

Still, homosexuality was illegal– under paragraph 195, to be exact. Blackmailing was rampant. So before he even founded the institution, Magnus got his friends together to form “The Scientific Humanitarian Community,” which was essentially the first LGBT advocate group.

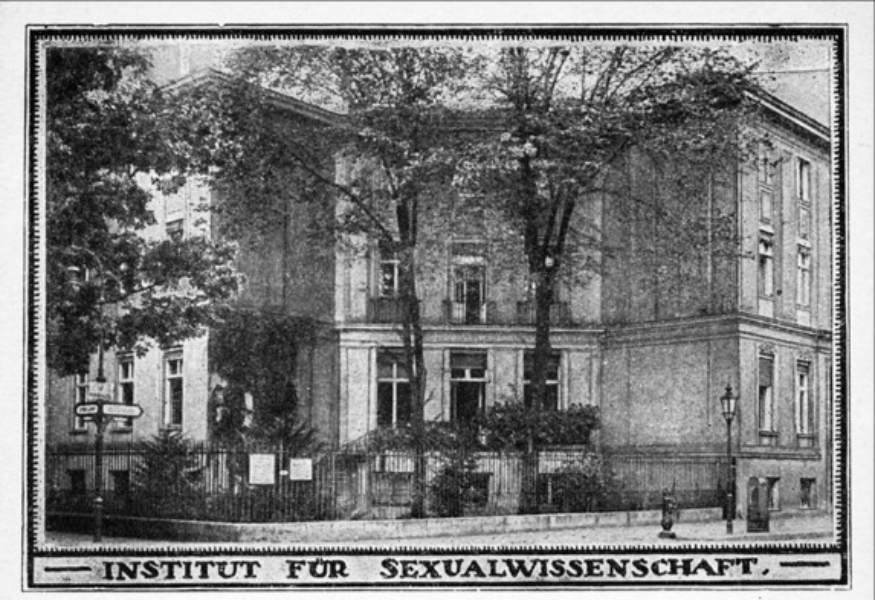

By 1919, he’d founded his sexual Institute in a villa in the centre of Berlin. There was always a box perched on the villa’s edge, in which visitors could drop their burning questions and concerns anonymously.

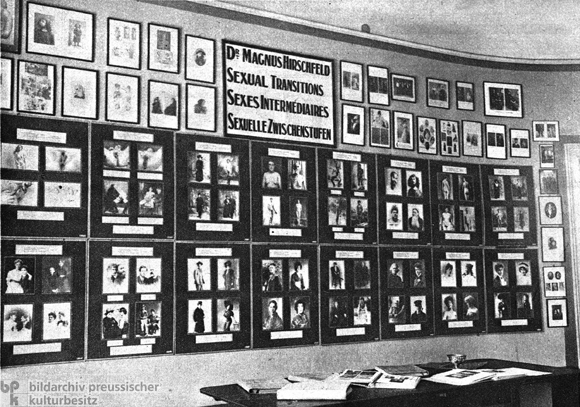

Today, sadly, we’ll never know all the details of the institution’s many creations. But we do know it was also incredibly on the ball with public sex education, “examination rooms, a library and a sex museum that was apparently a big tourist attraction,” explain Elah Feder and Annie Minoff, producers of the Undiscovered podcast. According to the Hirschfeld archives today, “More than 40 people worked at the Institute in many different fields: research, sexual counselling, treatment of venereal diseases and public sex education.”

Magnus was above all a really good people-person, and it was his charisma that made the centre a place of not only serious study, but a kind of Disneyland for the sexually curious. “The rich and intellectual elite of Europe, from movie stars to poets such as W.H.Auden, came to visit the museum,” explains The Guardian’s David Cox in 2017, “which contained everything from basic sex education to the institute’s research into transsexuality”.

Magnus also co-wrote Different from the Others, believed to be the first pro-gay film in the world and the first time a gay character was portrayed on film:

As for Magnus, specifically? He studied some 5,000 gay men and women. “Some of his science doesn’t age that well,” explain Feder and Minoff, but he was still remarkably ahead of his time. Brush over his writings, and you’ll find studies about whether sexual orientation was linked to one’s ability to whistle– a stereotype, apparently, in the early 20th century– which Magnus went to disprove through his own research.

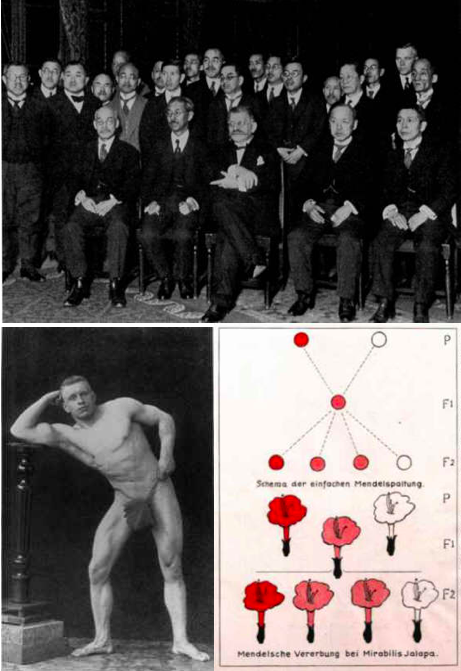

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, 1927. Credit: Courtesy Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin.Sometimes, his explorations went to testy waters– experiments that tampered with patient’s hormones, but Magnus’ heart was always in the right place. “Hirschfeld’s methods were unusual for a doctor of his era,” wrote Cox, “He believed that careful observation and talking at length with patients, often over long walks were vital to establishing a theory.” Soon he became world renowned, touring as far away as Asia to share his finds. In the blink of an eye, everything changed.

Magnus was away from Berlin to lecture in Munich in 1921 when he woke up in a hospital bed reading his own obituary. The paper reported that a “Magnus Hirschfeld had been killed by an anti-Jewish mob”. Now, clearly he wasn’t dead – but he was sent into a coma by a group of persons we still can’t identify today. What we do know, is Hitler was watching him like a hawk, and even targeted him in one of his speeches.

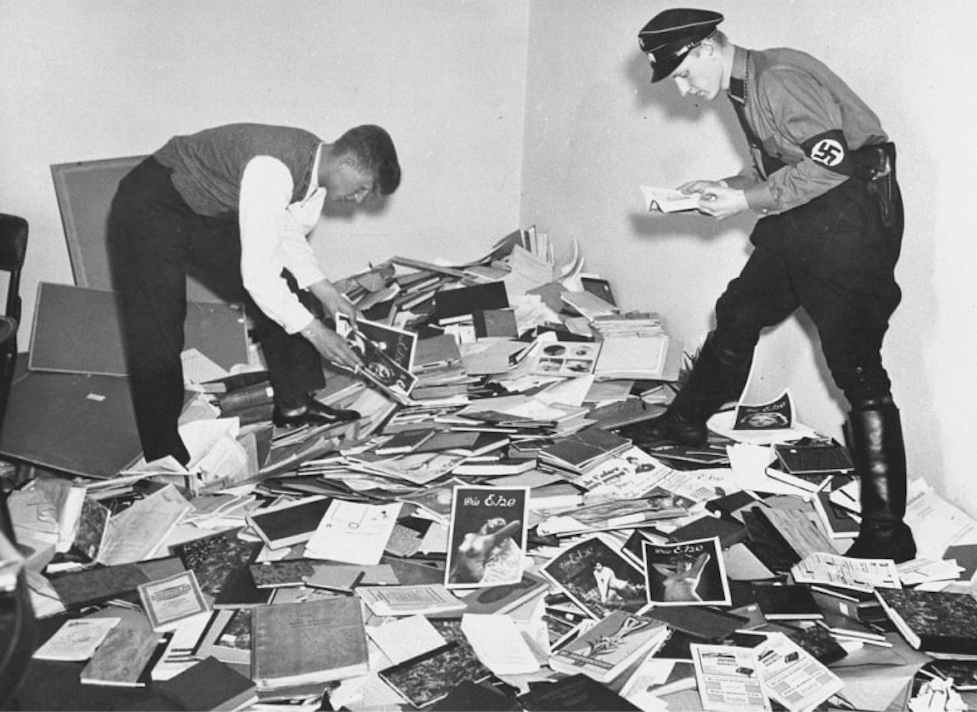

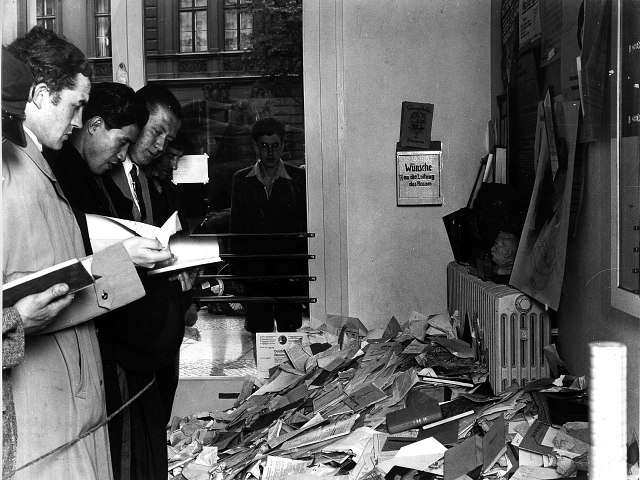

The boiling point was the morning of May, 1933. Nazi sympathising students gathered in front of the institution on a man-hunt for Magnus, who was actually in exile in Paris. Regardless, they pillaged and destroyed 30 years of research…

This wasn’t just a matter of eradication, but an opportunity for public shaming. A few days later, a book burning was organised at the Opera Square. Magnus stayed in France, hearing stories of how Fascist students paraded around with his bust on a spike as they burned his life’s work. Most heartbreakingly, out of all the experiments the institute conducted, it was the one that went terribly wrong which fascinated the Nazis most: hormonal experiments. Years later, a doctor at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp cited the institute as the inspiration behind his “conversion treatments” on gay prisoners in camps.

Magnus was crushed. He attempted to rebuild the centre in Paris, but to no avail, and lived out his days in Nice with his partner, Li Shiu Tong, to try to find some peace. He died from a heart attack in 1935, and sadly, his surviving colleagues were unable to reclaim the Institute’s property, as the post-war courts somehow found its seizure legal.

But that doesn’t mean Magnus’ work hasn’t been pieced together throughout the years. Old photographs, stories, and legends about what it was like at the villa remain. In fact, one of Magnus’ most groundbreaking operations, on a transgender woman named Lili Elbe, became the inspiration behind 2015’s The Danish Girl:

Finally, in 2011, the Federal Cabinet of Germany established a 10 million dollar Magnus Hirschfeld National Foundation to continue to uphold his research and advocate for LGBTQT in Germany. And while even the building Magnus’ sexual mecca thrived in was bombed to bits, the best thing we can do to ensure his story lives on is powerfully simple: tell it.