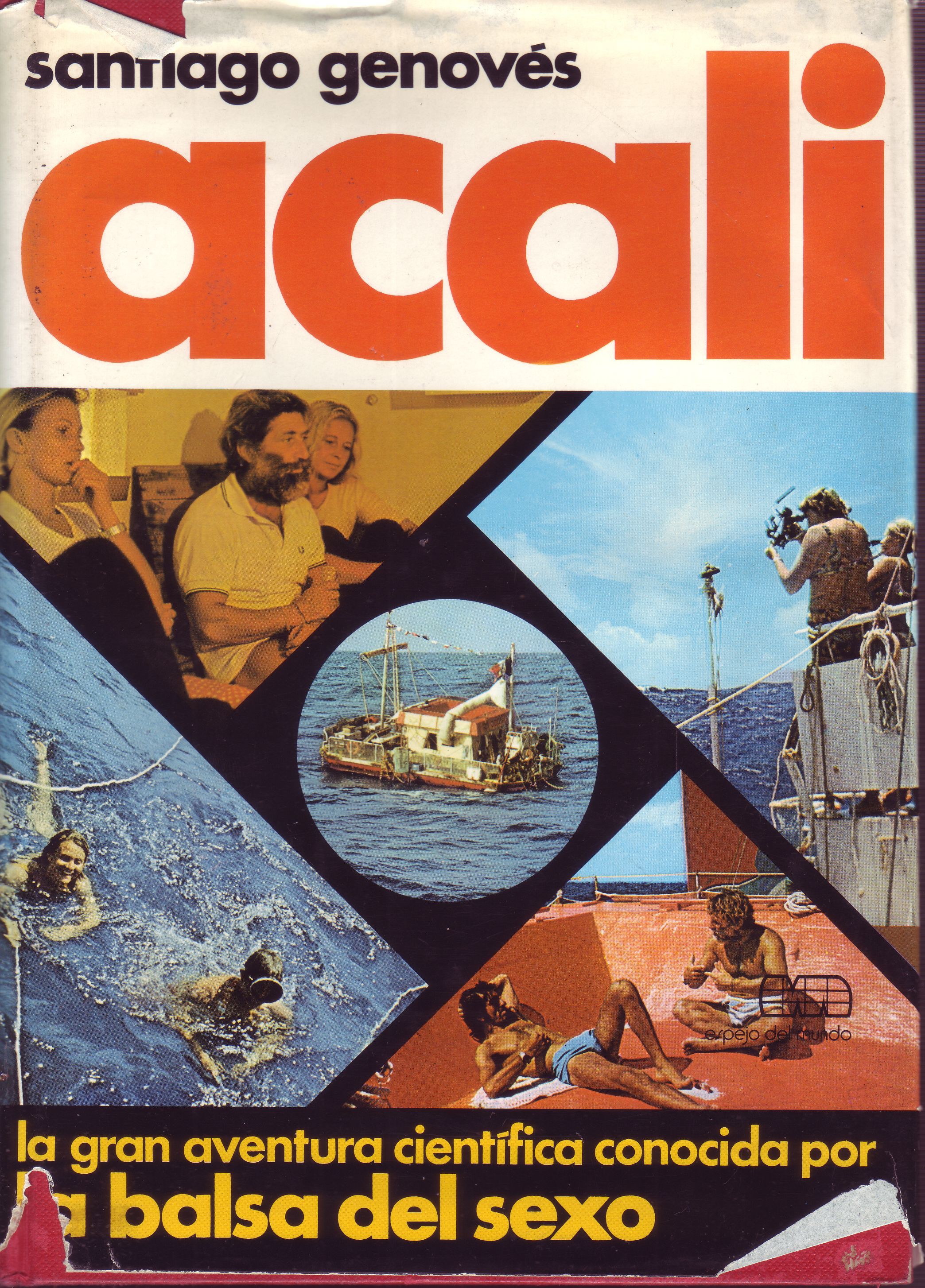

Fasad Productions

Five men, six women and one 101-day, sex-starved ocean adventure. Has a catchy ring to it, no? “It was a fabulous adventure story,” said Marcus Lindeen, director of a 2018 documentary called The Raft that chronicles 1973’s “Acali Experiment,” in which an eclectic group set sail to find out if the best– or worst– of humankind rears its head in isolation. With 10 attractive, young participants, naturally, the media focused on the sex, but the 1970s science project soon descended into a strange chaos. Think Wes Anderson’s Life Aquatic, but crazier.

The man behind the project was a “romantic” Mexican anthropologist named Santiago Genovés, says Lindeen. He had a degree from University of Cambridge, and already participated in various raft expeditions (we’d need another article to talk about the Ra I, Ra II, and Tigris adventures on ‘ancient Egyptian’ rafts), but the Acali trip was on a whole new level. “You cannot make an experiment like this on land, because people can escape” Santiago said when asked by the Associate Press in 1973 if it was really necessary to take such dramatic measures, “we want to see how much, really, a human person can endure.”

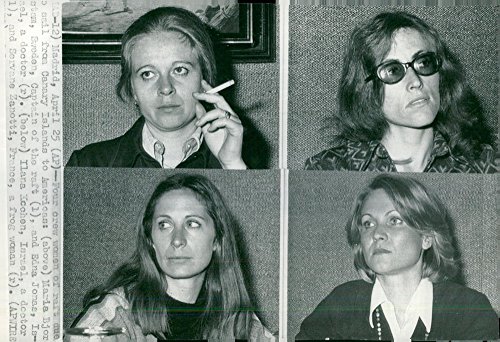

Participants Maria Björnstam., Edna Jonas, Ilana Kochen and Servane Zanotti.

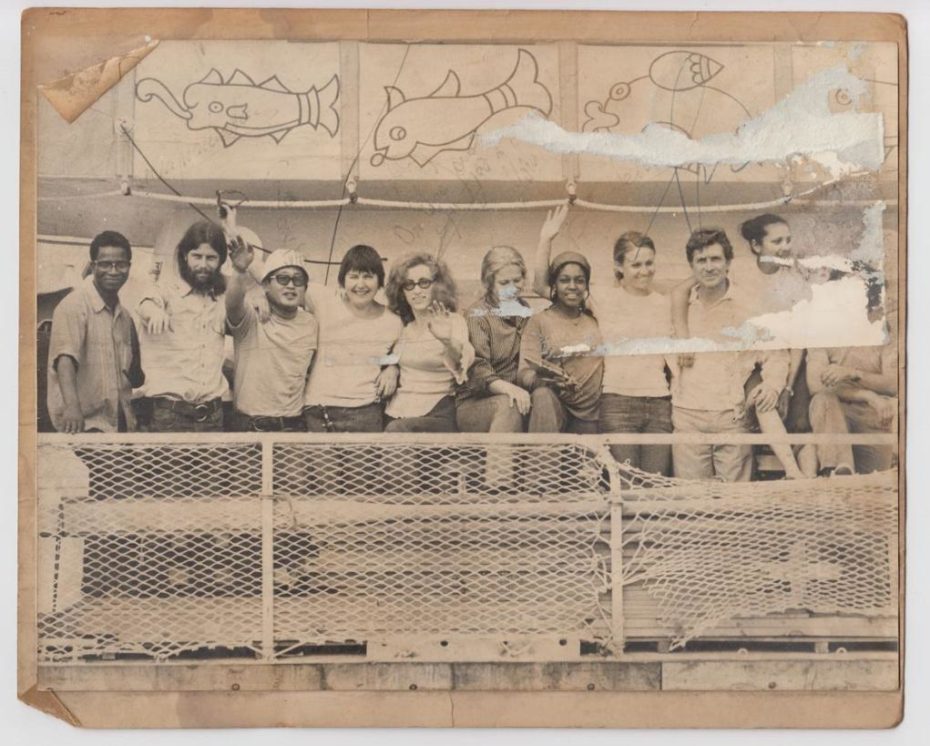

So who signed-up to call the 12×7 metre raft home? Santiago received thousands of messages when he put out ads. There were the published qualifications, but there were also others boxes Santiago was silently looking to tick; applicants had to be 1) preferably married, but agree to leave their partner for the trip 2) traditionally “attractive,” as Santiago said he was interested in observing sexual and romantic relationship developments 3) between 25-40 years old 4) diverse.

The participants on-board

The last bit is where things get interesting. Santiago was also very on-board with second-wave Feminism, and specifically wanted women to be at the helm of the ship– literally, and figuratively speaking. He chose Swedish sea captain Maria Björnstam (the world’s first woman to have a maritime command certificate) to steer them in the right direction, as well as a professional French female scuba diver, and a female Israeli doctor to come aboard.

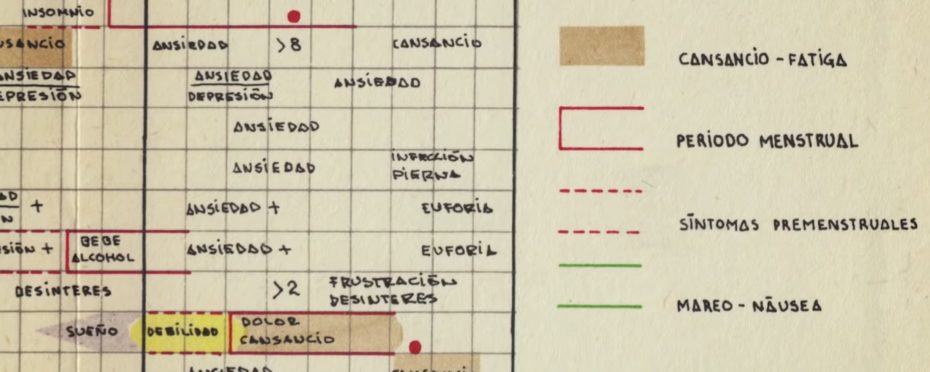

The media might’ve billed the adventure as a “Sex Raft” escapade, but Santiago preferred to call it a “Peace Project,” ironically trying to answer what makes people hate each other. Also on board was an Angolan priest, a Japanese photographer, and an American woman who used the experience to escape an abusive relationship. With their ties to the real world cut, and their minds open, they set sail. During the journey, the participants had to fill in a number of forms about relationships, masturbation and the like.

The goal was to traverse the Atlantic to the Mexican Peninsula of Yucatan, and according to Guardian journalist Stuart Jeffries, “To spur conflict onboard, Genovés minimised opportunities for privacy. His human guinea pigs were allowed no reading material. When they wanted to use the loo, they had to sit on a hole perched above the waves in full view of the other 10 and hope that the sea would wash their bottoms.”

But the lines between science, and Santiago’s blatant pandering for drama, got blurry. Consider the instance when the crew caught a shark. Santiago’s log recorded observations like, “Crowd frenzy! They are acting as part of a dangerous collective!” when the reality, the survivors say today in the documentary, couldn’t have been more different.

For African American engineer Fé Seymour, the experience struck an unexpected emotional chord, prompting her to think about the history of slave ships. “I would sit on the starboard side and look into the water. I would start to hear voices coming from down there … I would hear my ancestors call me,” she says in the documentary, “They could feel my flying over their bodies and their tragedies. It was one of the best things that happened to me.”

Now, hats off to Lindeen, who managed to reunite all the crew members from the trip for his documentary. Even though the voyage was reported on by the media, and actually sponsored by the Mexican Government, numerous participants had used fake names for the experiment.

The remaining crew today.

What’s more, Santiago died while Lindeen was still in the research phase of the film, and the storied 16mm camera that had been on board seemed impossible to find. “By pure luck, while I was at [Santiago’s’],” he says, ‘I found a document about the Acali experiment, where Acali was wrongly spelt (with two ‘l’ instead of one). So I went back to one archive and asked them to look again in their files, and finally, we found the lost footage. It was like uncovering a hidden treasure!”

A reunion scene from, “The Raft”

Lindeen created a life-sized model of the raft for the participants, who hadn’t seen each other since they were at sea, to talk about what really happened. For one, it turns out that in the face imminent catastrophe, Santiago forced the Swedish captain to back down from her position, which in turn led to a crew mutiny.

At one point, Seymour reveals they even had a Murder on the Orient Express-style death planned for Santiago, in which every crew member participated in his downfall. The float suffered rudder breaks twice, the compass broke and radio contact was lost for extended periods on several occasions. After three months at sea, the raft was towed in port on August 20th, 1973. We don’t want to reveal all the juicy details of what happened, but we will say this: think twice before you ever sign-off on hopping aboard the next love boat.

The Raft (or Flotten in Swedish) is now showing in independent cinemas.