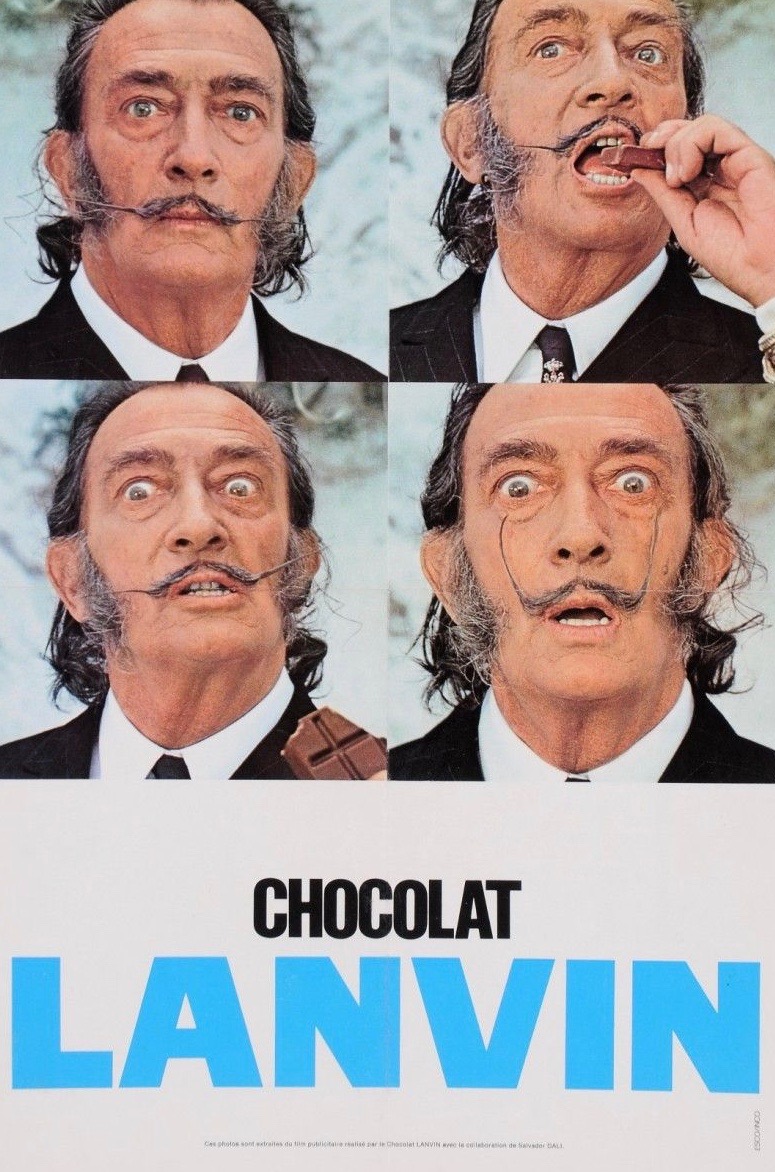

“Then the Alka Seltzer shoots into the stomach!” are words you might not expect to hear from Salvador Dali from the comfort of your own living room. Yet, for anyone with a television in the 1960s and ’70s, the Surrealist legend also became a staple of the small screen, sharing his abounding, rehearsed excitement for ads about chocolate, and ink wells; airline companies and cures for indigestion. Naturally, critics and creatives lost it. Dali, they declared, had finally reached his tipping point. Today, 30 years since his death, the dust of the gavel has settled, and we found ourselves wondering: what should we do with the Dali legacy everyone would rather forget?

We’ll start off by retracing his advertising and commercial career, to see how he got to the Alka Seltzer level of commercialism, and reveal a few surprising collaborators along the way, from a stocking company, to Walt Disney…

Dali’s 1970s ads for Lanvin Chocolate

Artists are no strangers to commercial work, both as a launching pad and a side-hustle. Andy Warhol was a great shoe designer before his Factory years, Mucha was beloved for his beverage adverts, and Tony Duquette elevated department store displays to breathtaking heights.

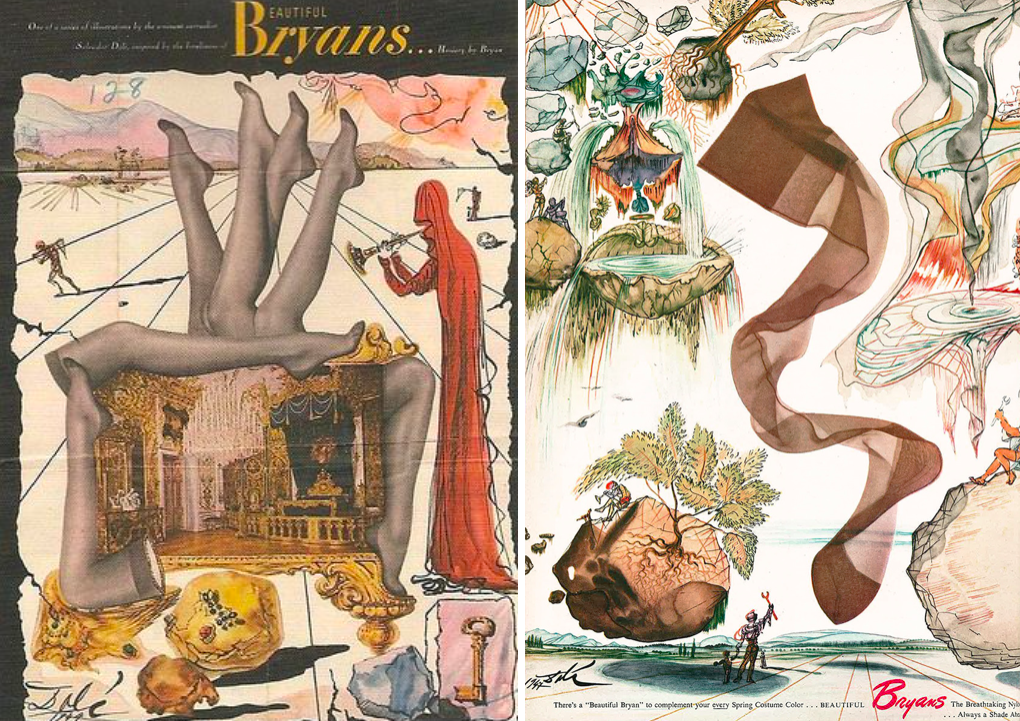

Dali’s stockings ads

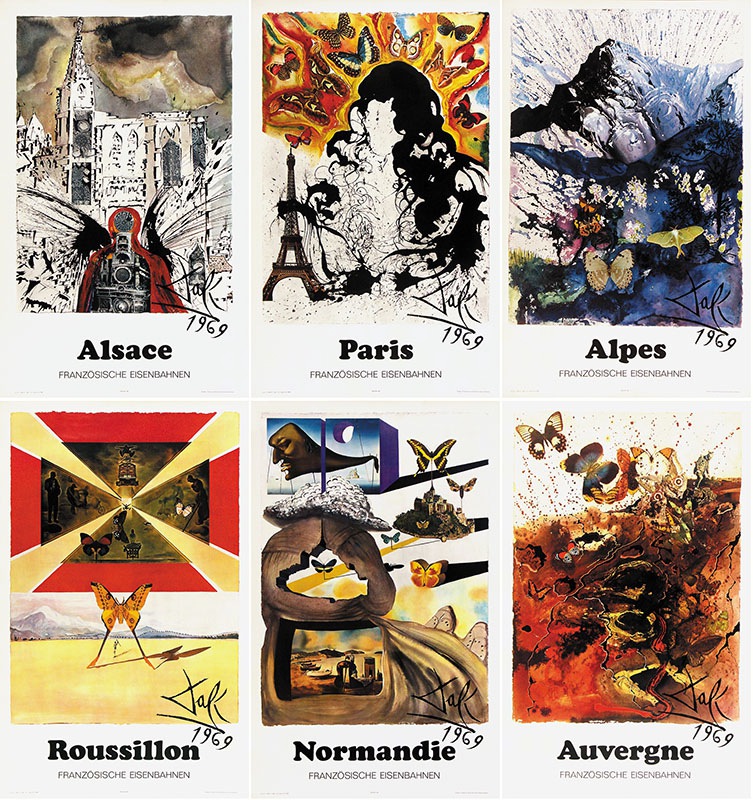

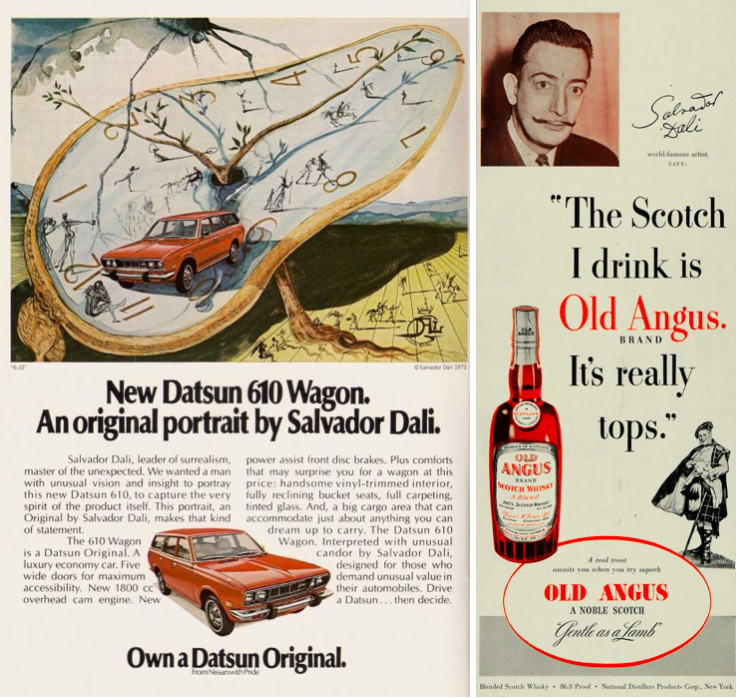

When Dali lived in America from 1939-1948, he also worked with many advertising companies, like Bryan’s Hosiery, Johnson Paint, various perfume and jewelry advertising companies– he even made some rather beautiful adverts for the French train company, SNCF:

SNCF posters by Dali.

Next, he dipped his toes in Hollywood by designing a sequence for Alfred Hitchock’s Spellbound (1945), and later landed a role in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s epic– but alas, ill-fated– 1970s adaptation of Dune, alongside Mick Jagger and Orson Welles.

Alfred Hitchcock and Dali’s dream sequence from “Spellbound” (1945)

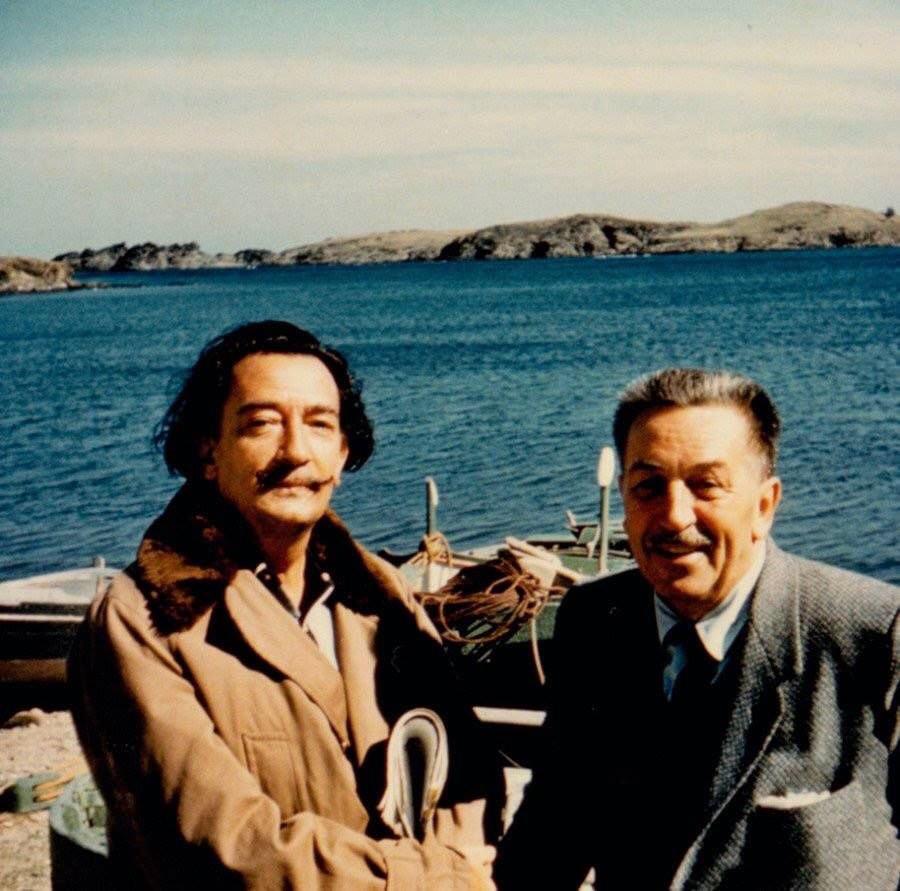

Both movies, even if one remains unmade, were creative masterpieces– and while we’re not implying Dali’s involvement in the movie industry was selling out, it did lead him to one of the movie industry’s biggest behemoths: Disney.

Walt Disney and Salvador Dali on a boat in Spain (1957) © Walt Disney Family Foundation Collection.

As legend goes, he met Walt Disney at a party one night, who told him he thought he’d be the perfect partner for a short film along the lines of Fantasia. But weirder. “I want to give more big artists such opportunities,” he said, “We need them. We have to keep breaking new trails.”

Walt Disney and Dali’s “Destino”

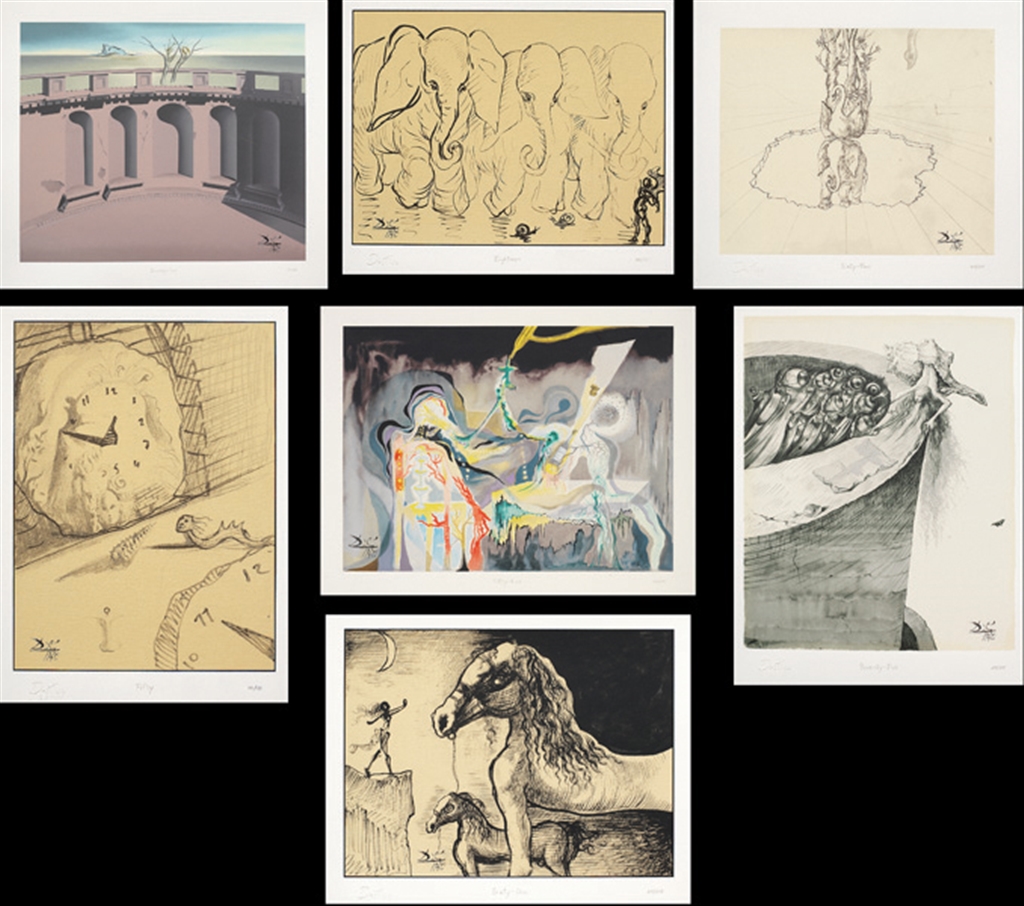

The project didn’t actually come to fruition until 2003, when Disney released a 6-minute film based on their conceptual work with their Parisian animation team, and director Dominique Monfery. Pictured above are Dali’s conceptual drawings, and below, Disney’s 2003 short film:

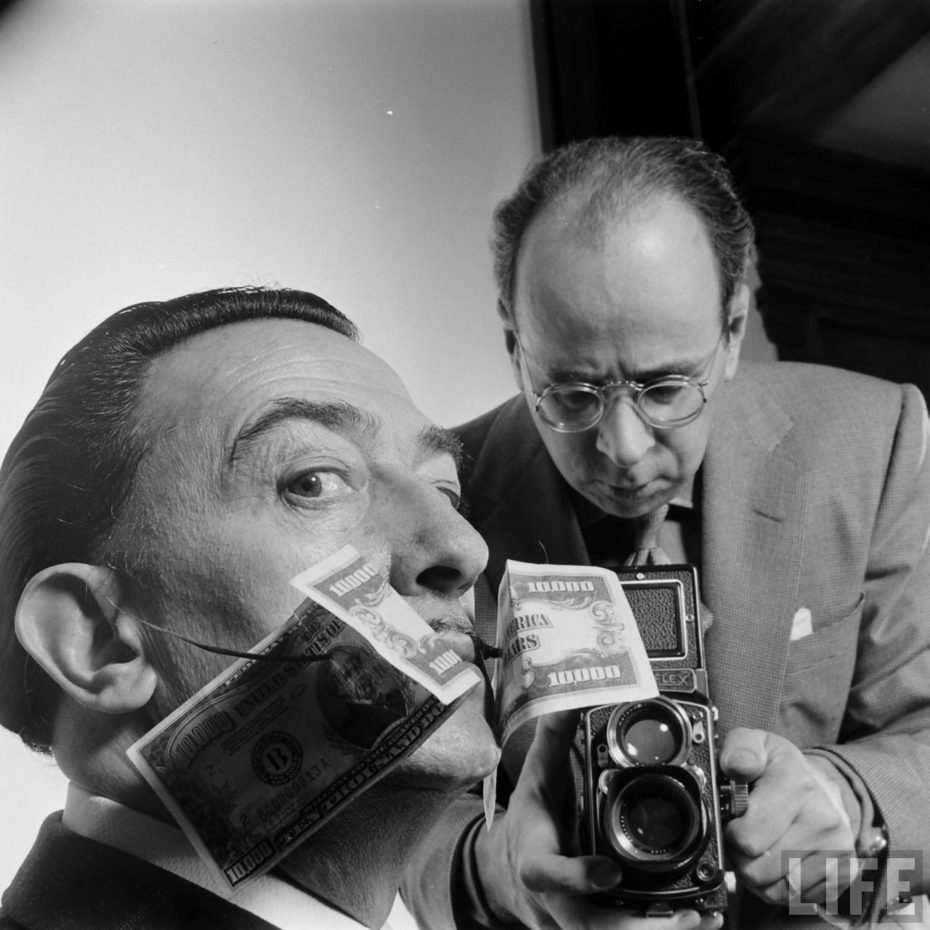

Walt’s words on fostering new talents, etc., is all very lovely– but for the Surrealists, Dali was entering enemy territory. Once a member of the European Avant Garde, they claimed he’d lost the very values that had shaped the Surrealist movement and its Marxist values. André Breton, who founded the movement in 1924 with his “Surrealist Manifesto” championed non-conformism, and an alignment with the working man against capitalist interests. Breton nicknamed Dali “Avida Dollars”, an anagram for Dali’s name and translates into ‘avid for dollars’. Breton believed that Dali was compromising the integrity of the surrealist movement.

In 1969, Dali was even responsible for one of the most successful commercial logos ever when he redesigned the famous Chupa Chups artwork, insisting that the Chupa Chups logo be placed on top (rather than at the side of) the lolly.

“From the 1960s everyone knew that Dali needed close to half a million dollars a month to fund his lavish lifestyle” explained journalist and Dali specialist Stan Lauryssens to Independent in 2009, “He was living like a mini-maharajah.” That lifestyle needed funding, and advertising was a solution. As you can see, he was a busy man, from selling chocolate bars to antacids…

Dali also had a whole lot of ego. “Having proclaimed himself a genius while in his 20’s,” explained New York Times art critic Alan Riding in 2004, “Dalí went on to promote this notion with such relentless conviction that the egotist eventually overshadowed the artist. By the time he died in 1989, leaving hundreds of signed sheets of paper to spawn a fake Dalí industry, many in the art world had turned against him.”

Life/ Time magazine

On the one hand, Breton is right. It’s not very bohemian to have a half-million-dollar-a-month lifestyle. Although, if we’re doing integrity nitpicking, Breton didn’t exactly make the Surrealist scene a freewheeling place for everyone (i.e. women!). But we digress. Our verdict? He’s not doing anything the contemporary art world wouldn’t condone today (Hi, Jeff Koons, Brian Donnelly, and every art fair ever). At the end of the day, we could continue intellectualising Dali’s commercials, or we could do something way better: watch them on repeat, while hanging out at his villa on the Costa Brava.