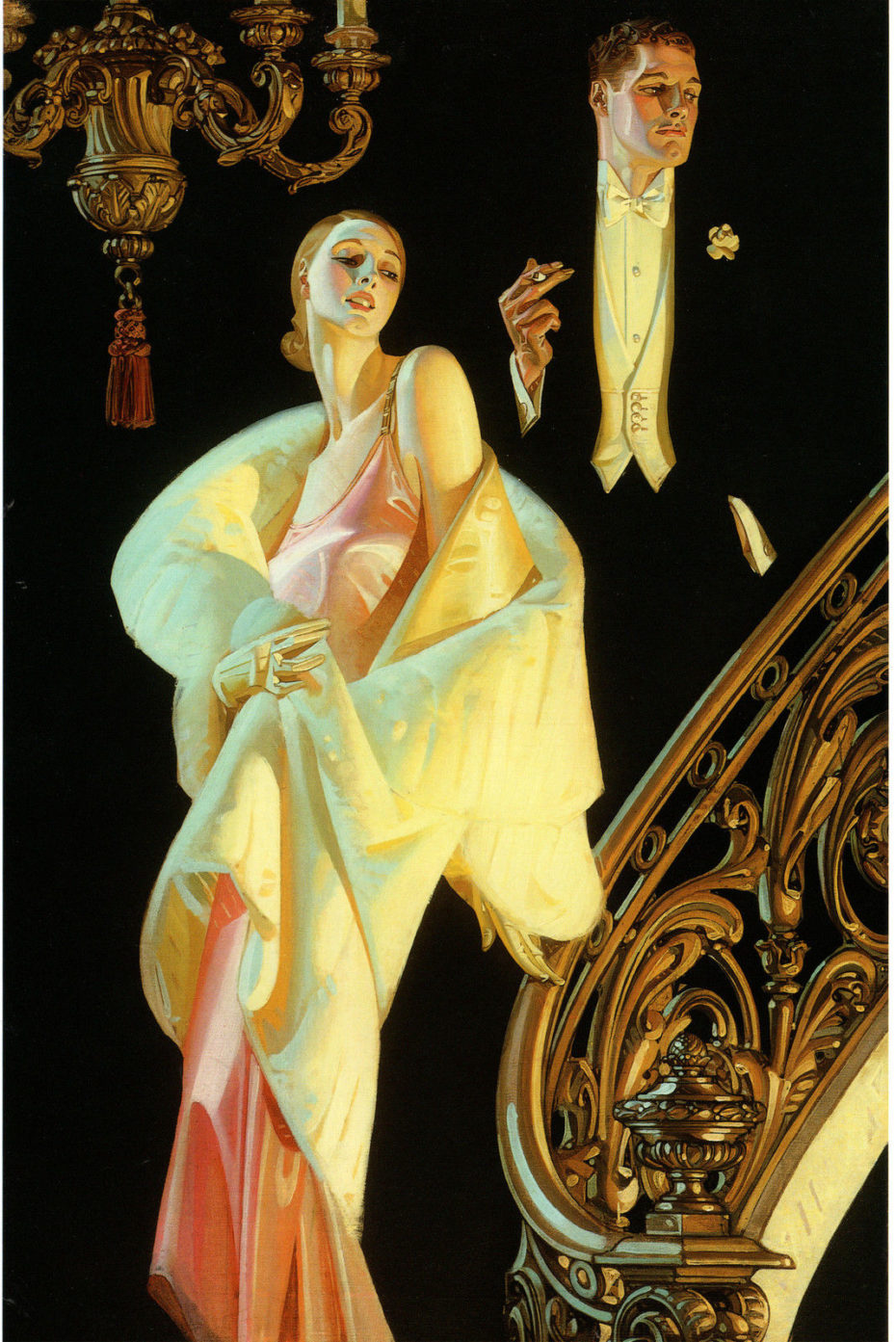

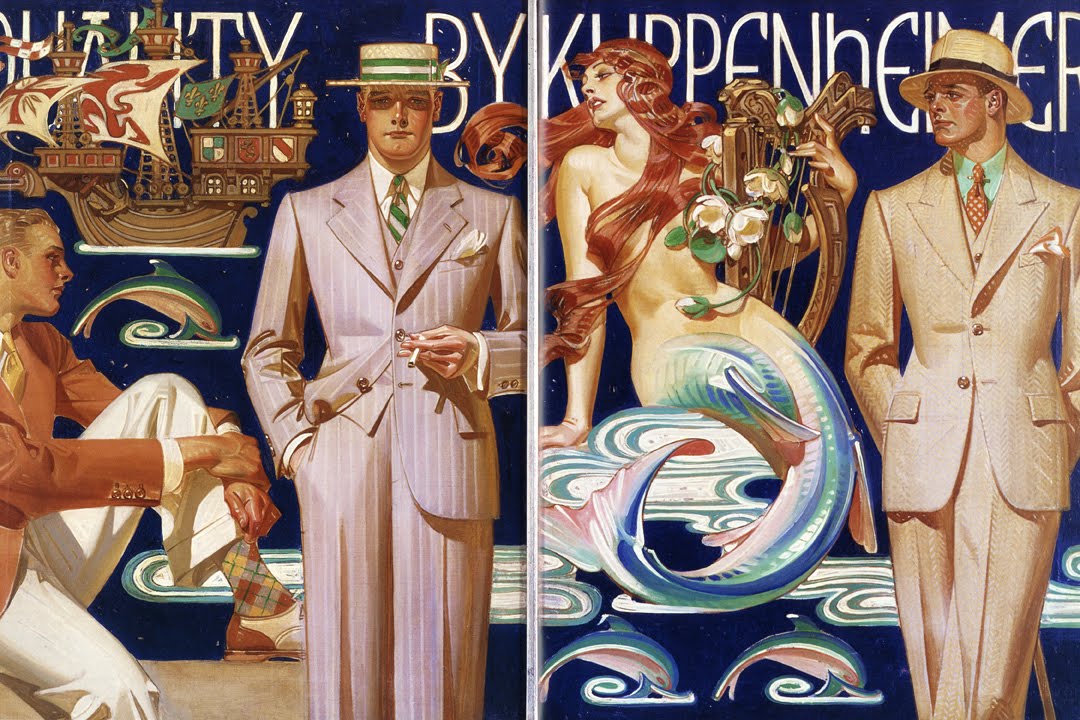

One of the first things you’ll start to notice about Joe Christian Leyendecker’s work is that his women were never quite as good-looking as his men, who were devastatingly handsome. He gave us the elegance of Gatsby 20 years before F. Scott Fitzgerald had even invented him. Take a moment to observe the dashing man on the stairs, who couldn’t be showing less interest in the girl standing below him in the provocative pink slip dress. His gaze is fixed on something, or someone else, and the viewer is invited to guess who that might be. Leyendecker created more than 400 magazine covers during the Golden Age of American Illustration, painting a picture of the new 20th century male and influencing millions of Americans, few of whom knew he was gay. Over a century later, as LGBT advertising is only now just starting to find a place in mainstream media, let’s take a look at the pioneering artist who in retrospect, hardly seemed to be hiding his sexuality at all.

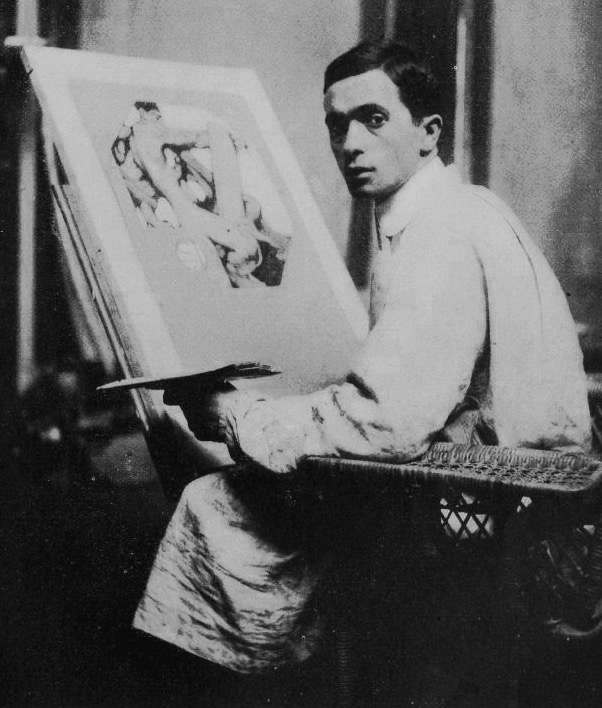

“Actually, it’s pronounced loin-decker”, was likely something Joe uttered a lot. A master depicter of oiled-up hunks, J.C’s ads appeared all across mainstream publications from the early 1900s right up until the Second World War.

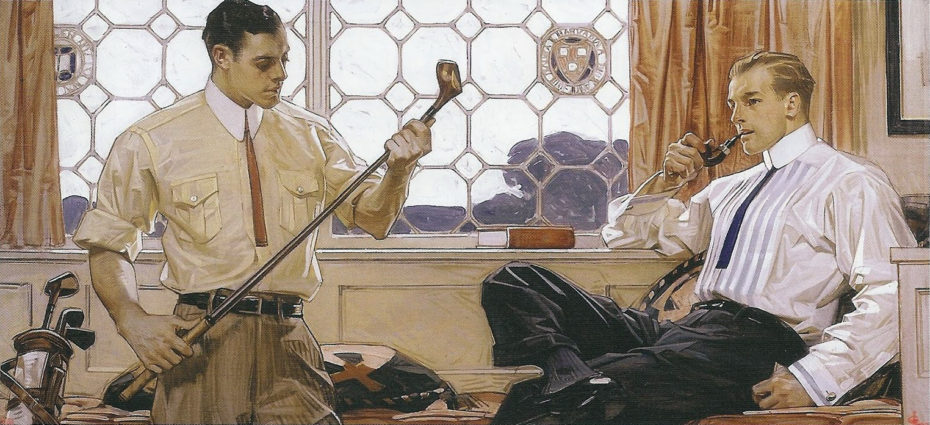

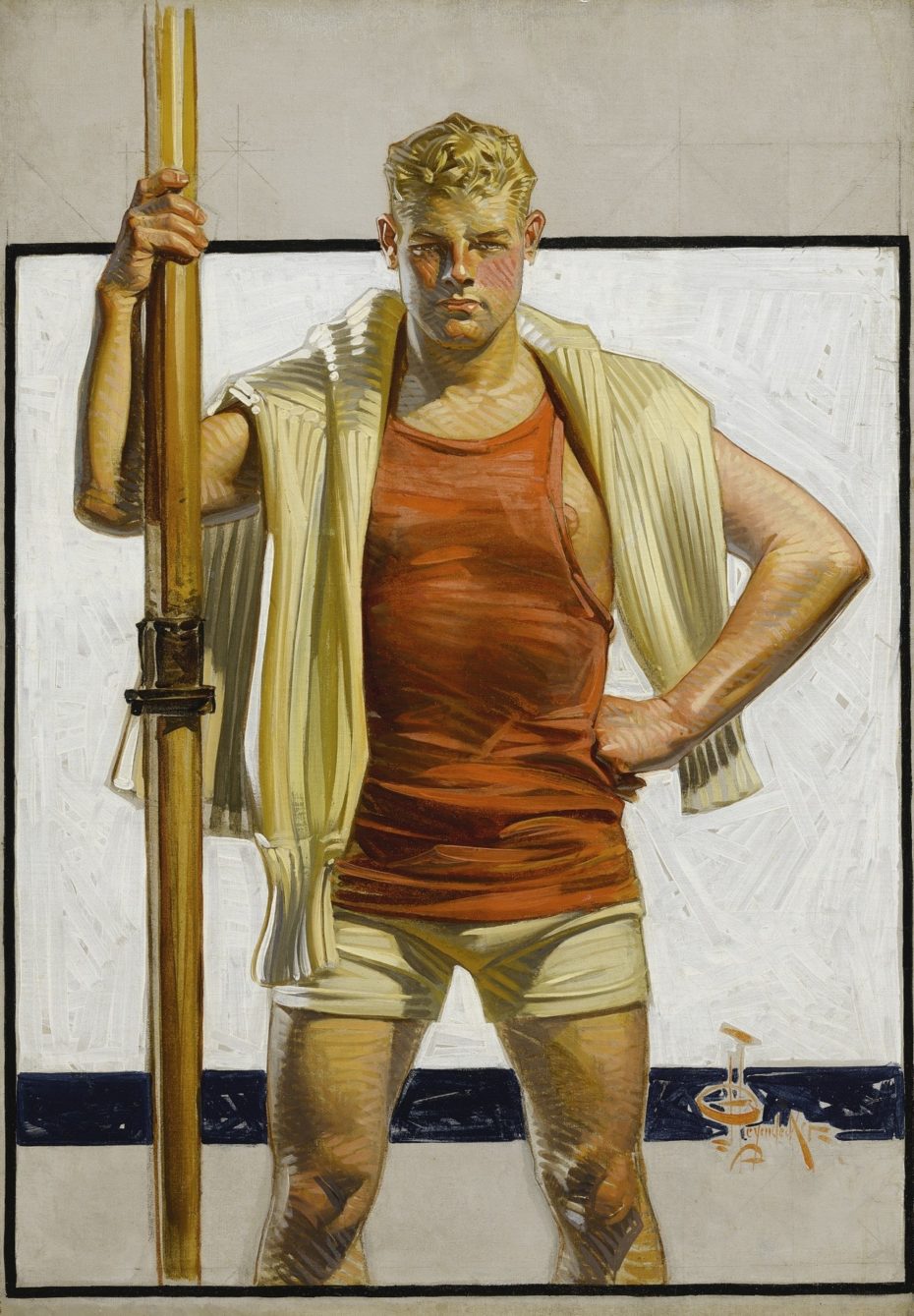

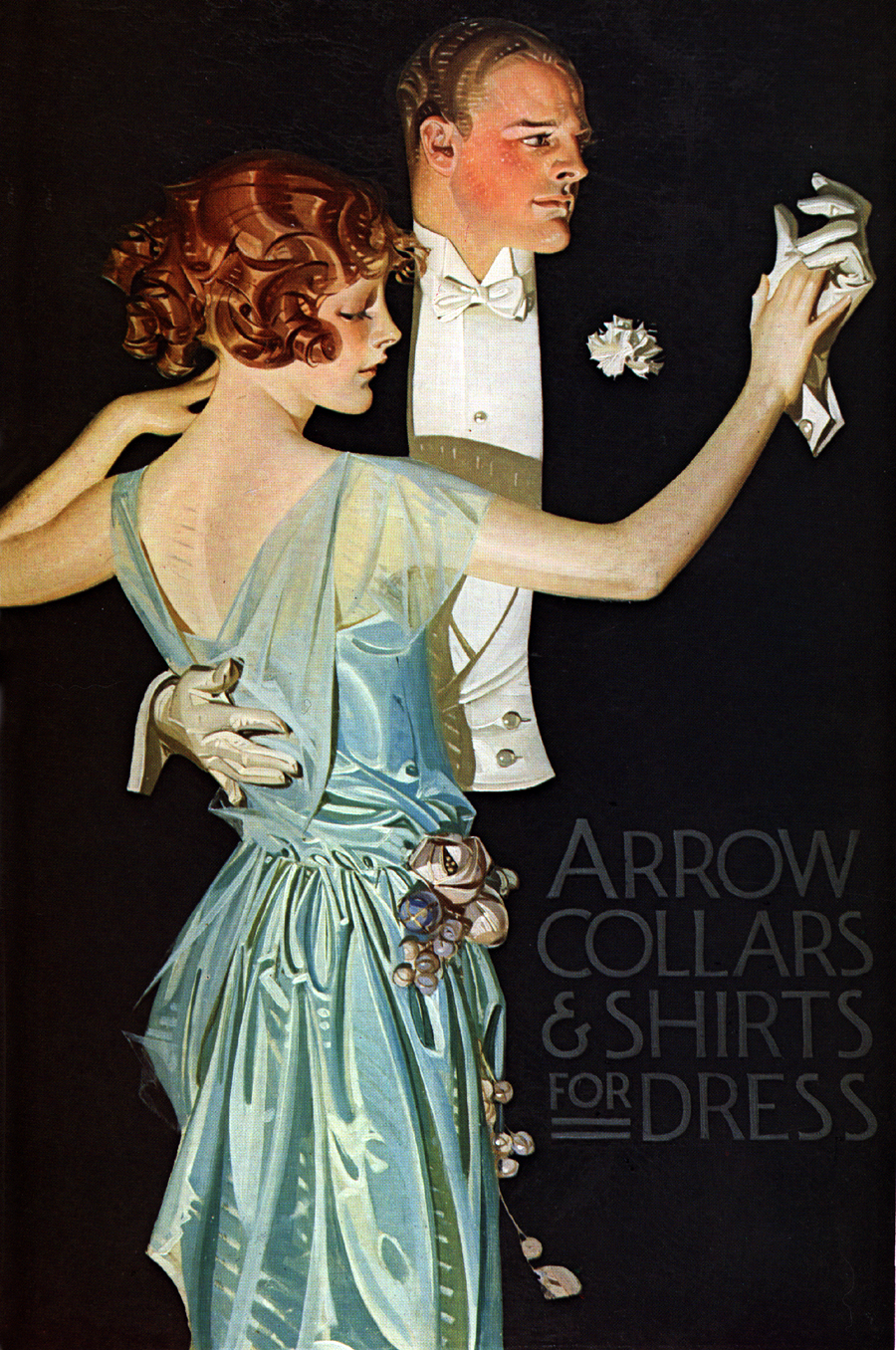

The new American male was muscular, often nearly-nude and almost always more interesting to look at than his female counterparts, hiding something in his pre-occupied gaze. Above, Leyendecker’s Gibson girl almost blends into the background as his golfers seem to be in a world of their own. Below, another handsome American male looks distracted as his dance partner appears to be the only one interested in their physical contact.

Joe was born in a German village on the Rhine, and emigrated to Chicago where he studied at the Chicago Art Institute, before going to Paris for a spell. The imprint of the groundbreaking art from those years, from Mucha’s curves to Lautrec’s flushed figures, is something that forever stayed with Joe’s work…

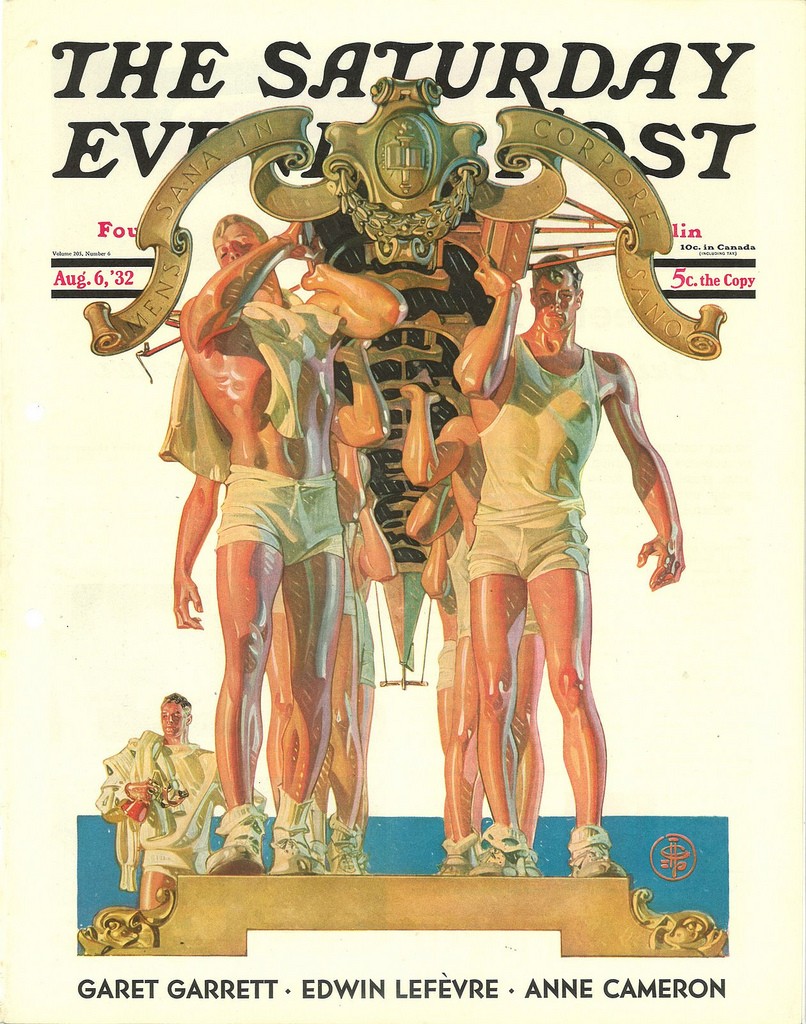

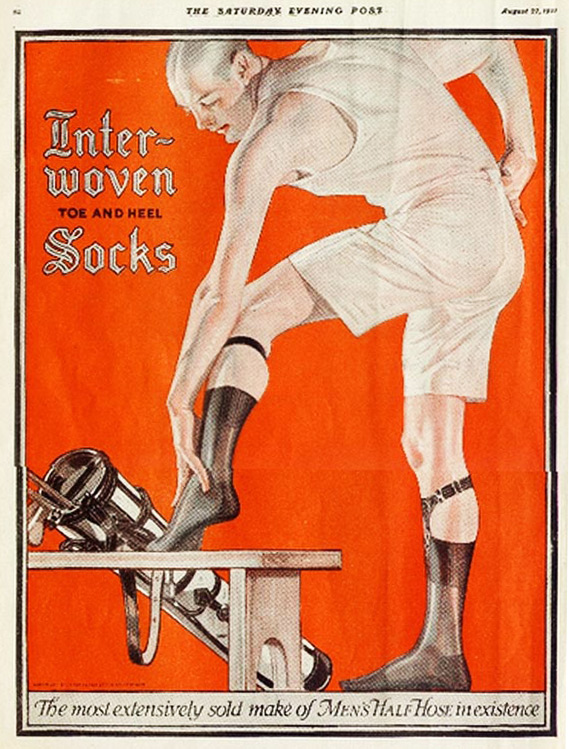

He returned to America in 1899 and hit the ground running, cooking up ads for everything from sock companies to the breakfast food manufacturer, Kellogg’s. He can even be credited with creating the pudgy red-garbed rendition of Santa Claus later adopted by Coca Cola. And most notably, in 1899, he began a 44-yr relationship with The Saturday Evening Post.

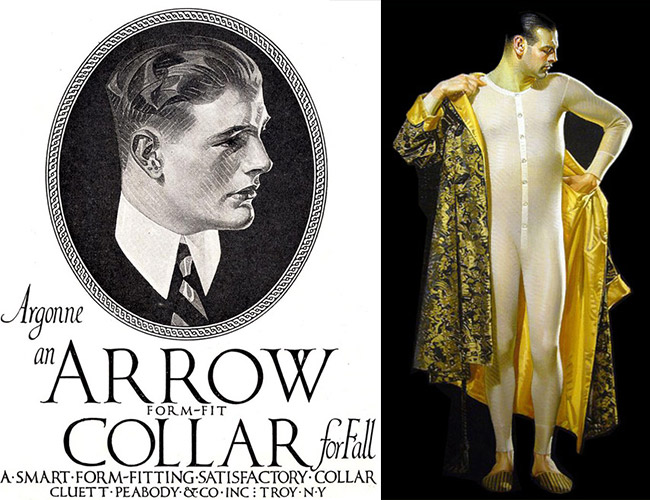

The magnum opus of his work however is “The Arrow Collar Man”, a character created for a shirt company who became one of the early-20th century’s biggest male sex symbols. “[He] had about as large a place in the pantheon of hotness as Rudolph Valentino, Elvis, and the Marlboro man,” explained Vogue’s Laird Borrelli Persson.

“The Arrow Collar Man predates Jay Gatsby by 20 years,” Persson notes, “and, critics believe, is referenced when Daisy Buchanan says to Gatsby: ‘You always look so cool. You resemble the advertisement of the man . . . you know, the advertisement of the man.'”

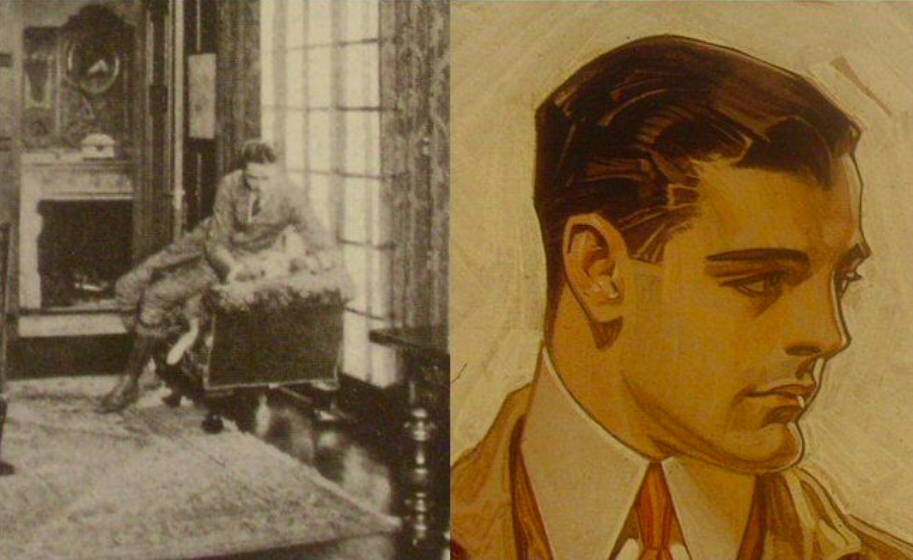

Americans were swooning, as was J.C., and with good reason: the model behind the Arrow Collar Man was none of the than the muse and love of his life, Charles Beach….

A rare photo of Charles Beach (left) and a portrait of him by the artist.

Leyendecker lived with Charles in a splendid house in New Rochelle, New York, where they threw party after party in true Roaring Twenties glory, embodying the decadence of the era and indulging in their own real-life Gatsby fairytale thanks to the artist’s success.

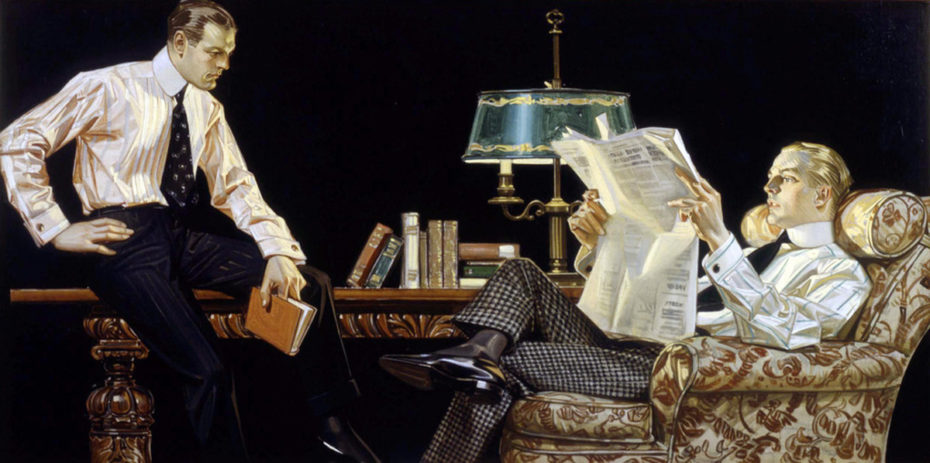

If Leyendecker’s sexuality was understood in the industry, it was kept quiet from the audience. But his work did all the talking, albeit in coded messages; suggestive side staring, a preference male-centric environments like locker rooms, clubhouses and tailoring shops. It’s as if Leyendecker was trying to communicate with a gay audience through secret glances and homoerotic undertones. Wartime was also a good space for homoeroticism to hide in plain sight and J. C. painted numerous recruitment posters for the United States military and the war effort.

“[Leyendecker] created a counter-image to the Teddy Roosevelt Rough Rider,” explains James Gifford in Dayneford’s Library: American Homosexual Writing, 1900-1913, “appropriating its athleticism but refining it into a male standard with an Americanised version of the Wildean dandy.

One of J.C’s greatest admirer’s was Norman Rockwell, one of America’s most iconic painters. “Rockwell virtually did everything possible to imitate Leyendecker,” says the American Illustrators Gallery, while the latter “received little adulation or credit for his truly iconic images.”

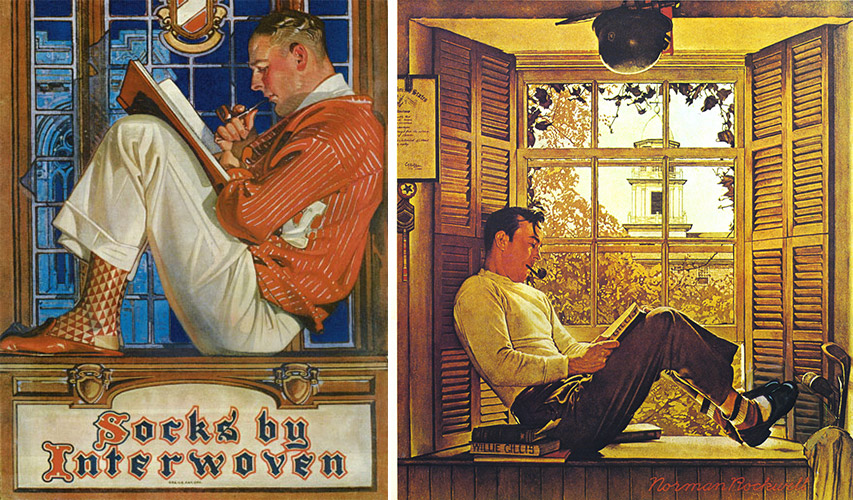

Leyendecker left, Rockwell right

Collector’s Weekly cleverly points out this side-by-side comparison of their work above.

As time worn on, Leyendecker’s men fell to the wayside of Rockwell’s rosy, small-town USA vision of Americana– which isn’t to discredit Rockwell’s talent or ingenuity, but simply give credit where credit it due. The two did have their differences, after all; just have a gander at the works they made associated with Thanksgiving…

(Left) a Thanksgiving ad by Leyendecker, right by Rockwell.

J.C was hit hard by the Wall Street Crash of 1929. By 1943, his editor at The Saturday Evening Post retired, the war was gearing up, and Joe ended up living out the rest of his days with Charles in New Rochelle, welcoming few visitors. Norman Rockwell was a pallbearer at Leyendecker’s funeral. It’s said he told Charles to “destroy everything” upon his death– every love letter, telegram, you name it– that could reveal their relationship. But his true self could never be erased from the loving brushstrokes of every single Arrow Man.