There was another Hollywood that thrived once upon a time. From the 1910s to the 1950s, an independent Black American film industry was in full swing, making movies specifically for an all-Black audience, with its own African American directors, stars and studios. The movies they produced, the first alternative American “indie” cinema, are known as “race movies”. Of more than 500 motion pictures made, nearly all have been destroyed or damaged and are now considered to be lost films.

To understand how race movies came about, we first need to take ourselves to the picture house at the turn of the century. In popular white culture, in the press, in cartoons and now on the silver screen, African American audiences are not only being ignored, but constantly insulted with demeaning images of themselves, portrayed as illiterate and uneducated, having never moved on from the plantations, never having advanced. At best, they are comedians, illiterate and uneducated; their roles serving only to provoke laughter and ridicule certainly not to provoke any kind of serious thought.

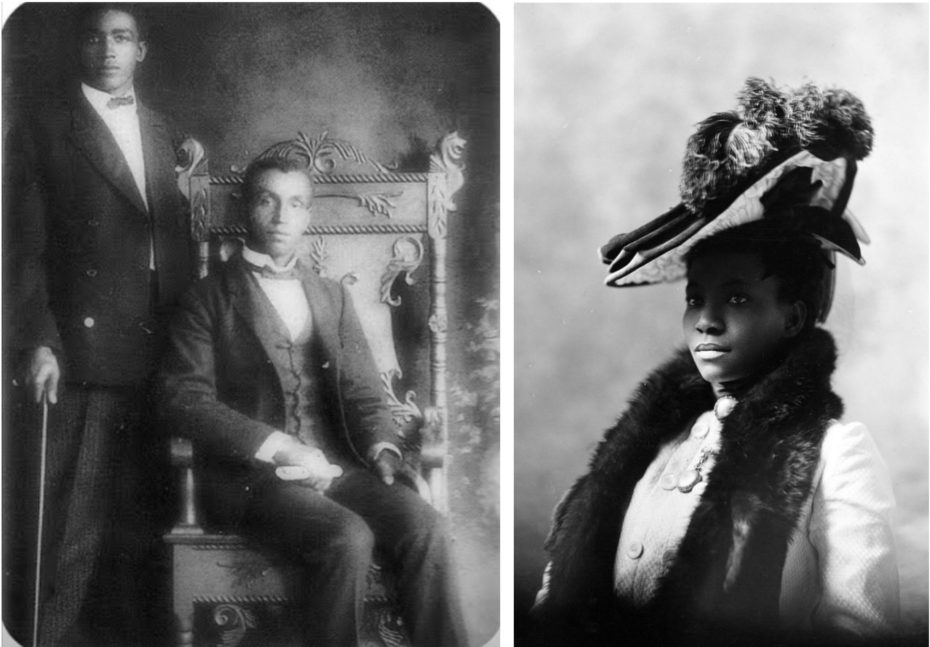

In reality, a sophisticated black middle class had emerged from the previous enslaved generation, one that needed to construct and see a new dignified image for itself that they couldn’t find in the regular cinemas, which were also segregated of course. The demand for a film industry geared to portray black society with affection and pride was brewing.

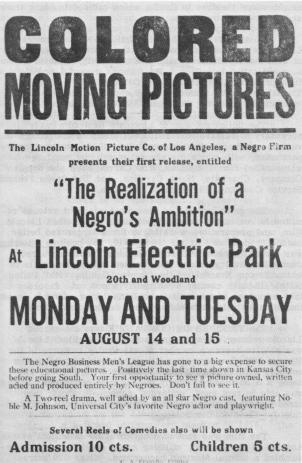

“Black Hollywood” found its audience in Chicago, a cultural centre for African Americans in the first two decades of the 20th century. Lincoln Motion Picture Company is considered the first all-black movie production company, and the first to create serious dramatic films. It was founded by an African American actor, Noble Johnson, who got his start in Hollywood playing Native American tribesmen, Egyptian soldiers and “exotic” merchants, but never his own race.

In 1916, he cast himself in his studio’s first movie as a young black engineer who strikes oil and becomes a millionaire. The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition became the first successful “Class A negro movie” box office hit. Due to segregation laws, Lincoln studio’s films were limited to show in churches, schools, “Colored Only” theaters, or midnight screenings, but they had a highly-professional look to them.

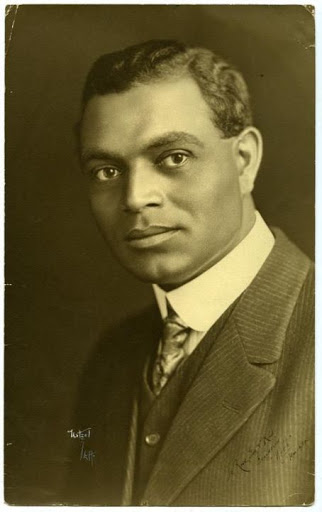

The Lincoln Motion Picture Company however, was short-lived, and closed in 1921. But not before the studio scouted the man who would become “the most successful African-American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century”. In 1918, Lincoln bid on the rights to adapt the first novel of an unknown rancher-turned-writer, Oscar Micheaux.

The farmer from South Dakota demanded the right to direct the movie himself. Lincoln resisted, so Micheaux decided to make the movie without them.

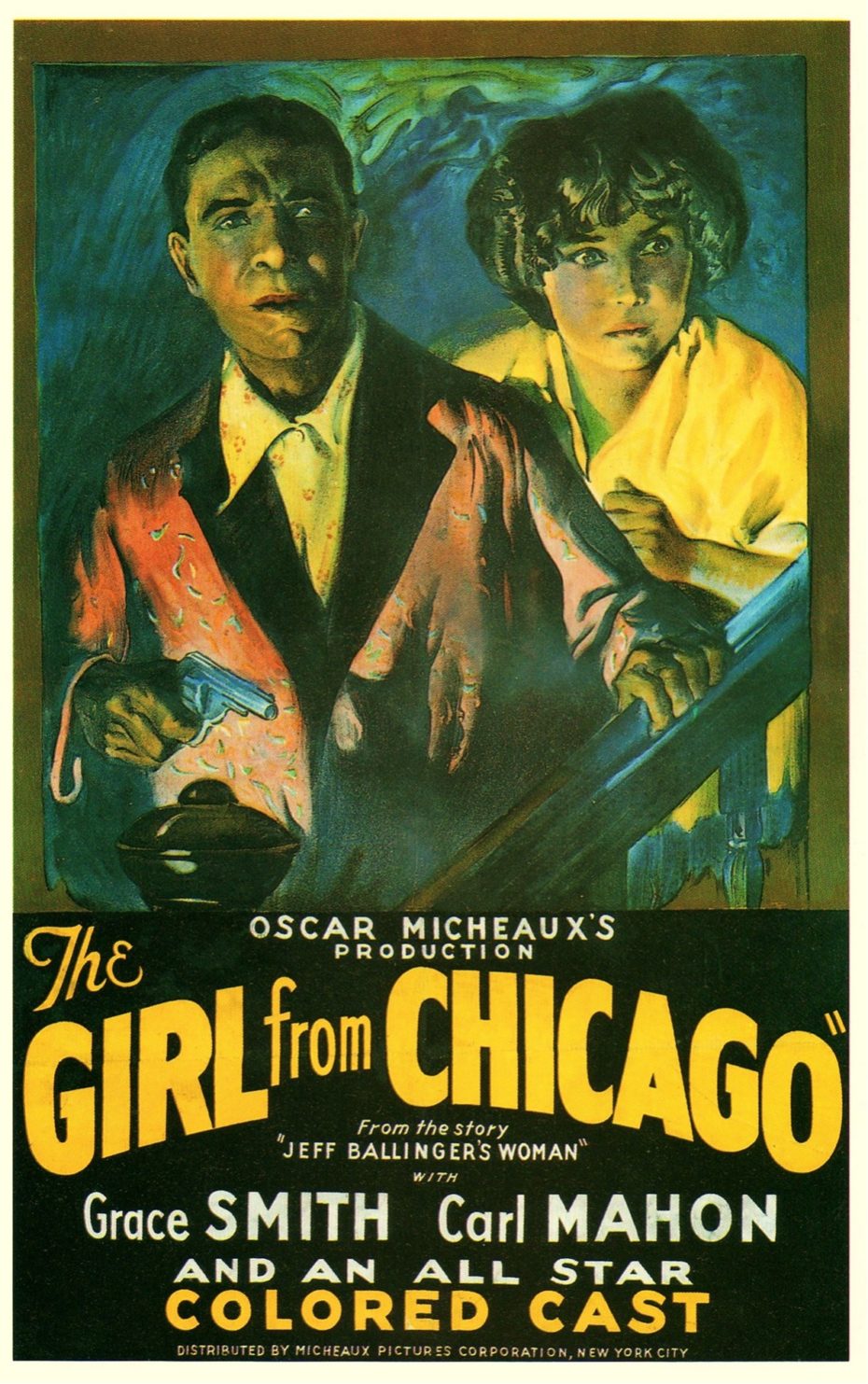

The Homesteader would become the first feature length race movie and Oscar Micheaux would go on to write, direct, produce and distribute more than 44 films over the next three decades. Less than a dozen survive. One of his films thought lost was discovered in a Tennessee garage in 1992. The trailer and fragments from two reels were restored by the George Eastman House and are currently preserved in the Library of Congress. The original film’s running time is unknown.

His films focused on the need for education and his characters were prosperous, and genteel. Confronting social issues of the day, unafraid of offending the sensibilities of the audience, both white and black, Micheaux hoped to give his audience something to help them “further the race”.

Finally, black Americans could see themselves as lawyers, cowboys, even royalty, and they weren’t gambling, drinking, stealing chickens, shooting craps or any of the other stereotypes that white Hollywood had chosen for them. If these kinds of stock characters appeared in race movies, they were most often relegated to villainous roles. Meanwhile in mainstream Hollywood, Hattie McDaniel, was awarded an Oscar in 1940 for her performance as “Mammy”, the demeaning dim-witted servant in Gone with the Wind. During the height of their popularity, race films were shown in as many as 1,100 theaters around the country as an antidote to racism and stereotypes in the entertainment industry.

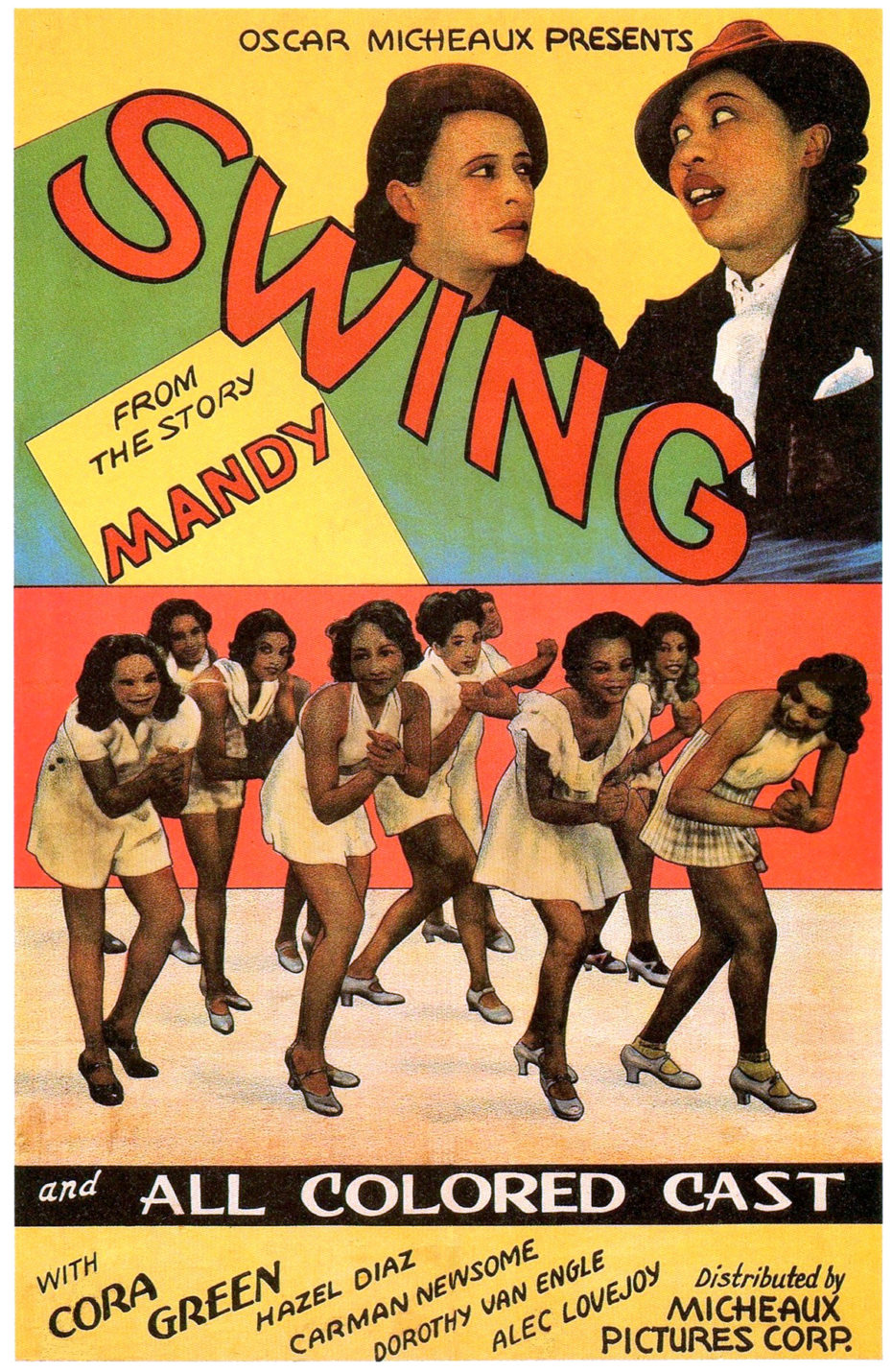

With the introduction and excitement of sound and talking pictures, race movies tried to duplicate what was becoming Hollywood’s Golden Age of musicals – on a shoestring budget by comparison. Race movie studios looked to Harlem to borrow its theatre stars that had emerged from the 1920s renaissance. Many notable black singers and bands began appearing in lead or supporting roles for the race film industry. When Lena Horne made her debut in a race movies, Hollywood took notice…

Mainstream studios started to look at race movies as a recruiting source for black talent. White producers also began to produce race movies and dominate the market. Soon enough, race movies were no longer doing their job. The difference between race movies and all-black Hollywood films began to fade and by the late 30s, the industry was forced to adapt to a shrinking market.

African-American participation in the war contributed to the casting of black actors in lead Hollywood. Names like Ethel Waters, who had got her start in race films, James Edwards and Sidney Poitier began appearing on major billboards. Race movies no longer had a future and after WWII, they had vanished entirely.

Fewer than one hundred examples of race movies produced have been preserved. Only one reel of footage from Lincoln Pictures, the first all-black movie production company, survives today.

Having been largely forgotten for decades by film historians, who weren’t looking outside of the Hollywood establishment, it wasn’t until the 1980s that some of the race films resurfaced on the BET cable network.

An entire industry apart, built and funded by black entrepreneurs who defied convention and acted as forefathers of American indie cinema at the turn of the century – almost wiped out. Almost. And the few films that have survived serve as proof.

In 2016, a Kickstarter campaign funded the restoration of a special collection of race movies for public release. Martin Scorsese has called them “essential viewing”.

Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1920) and a few others are also available to watch online for free on the Internet Archive.