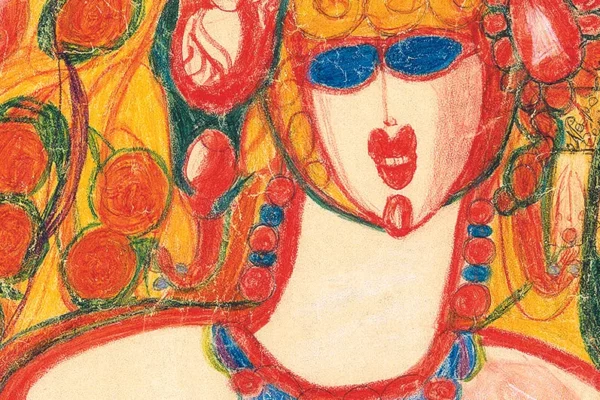

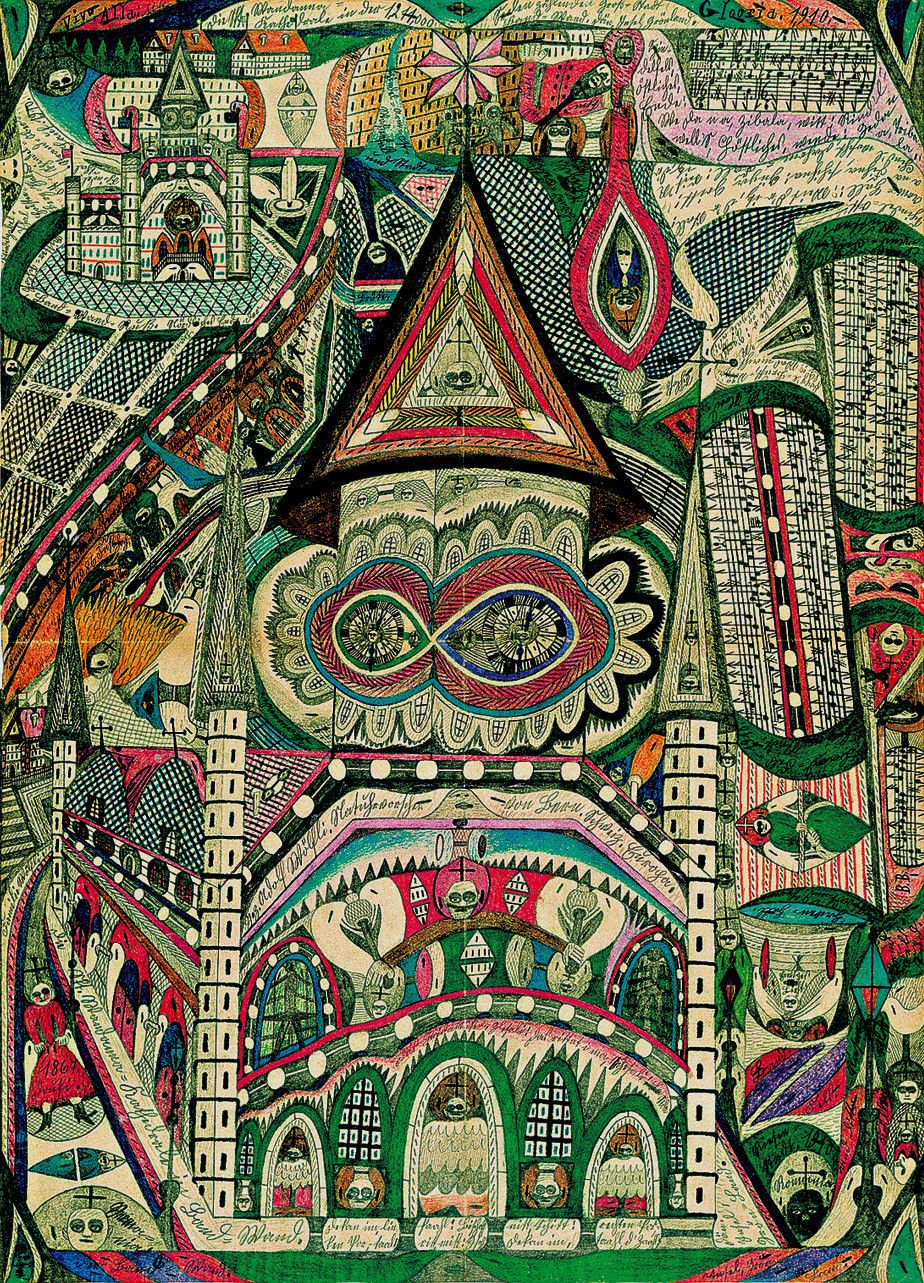

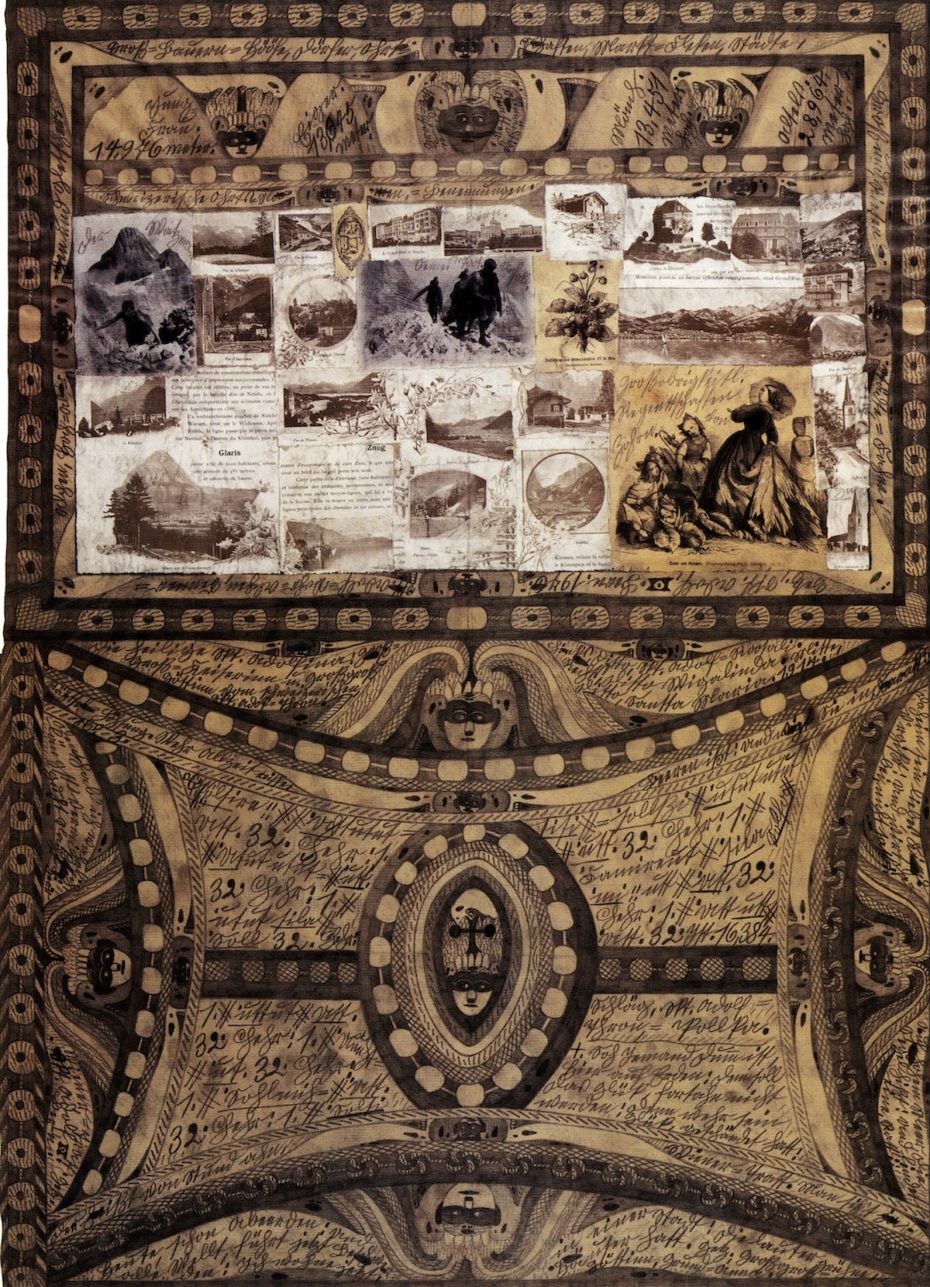

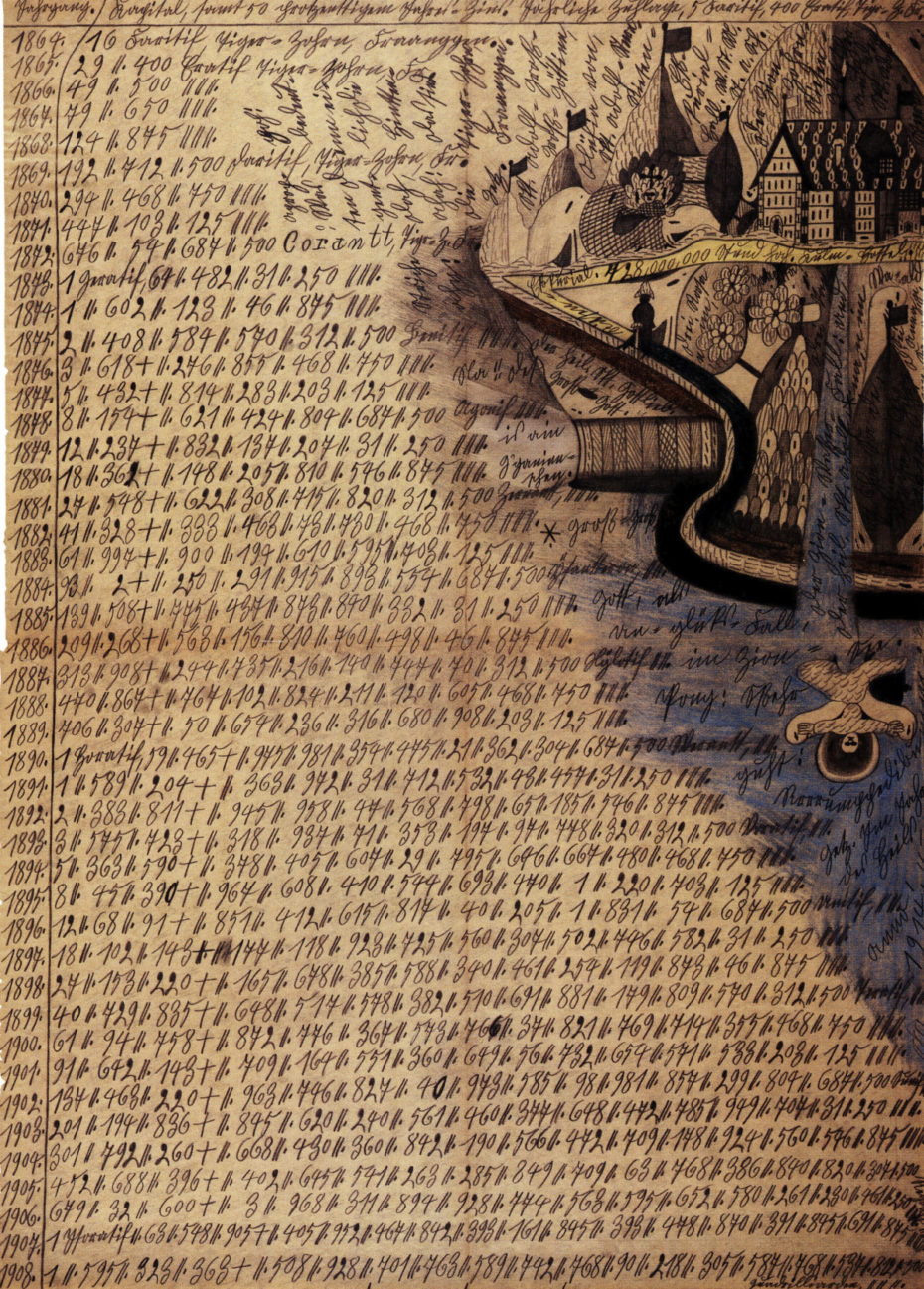

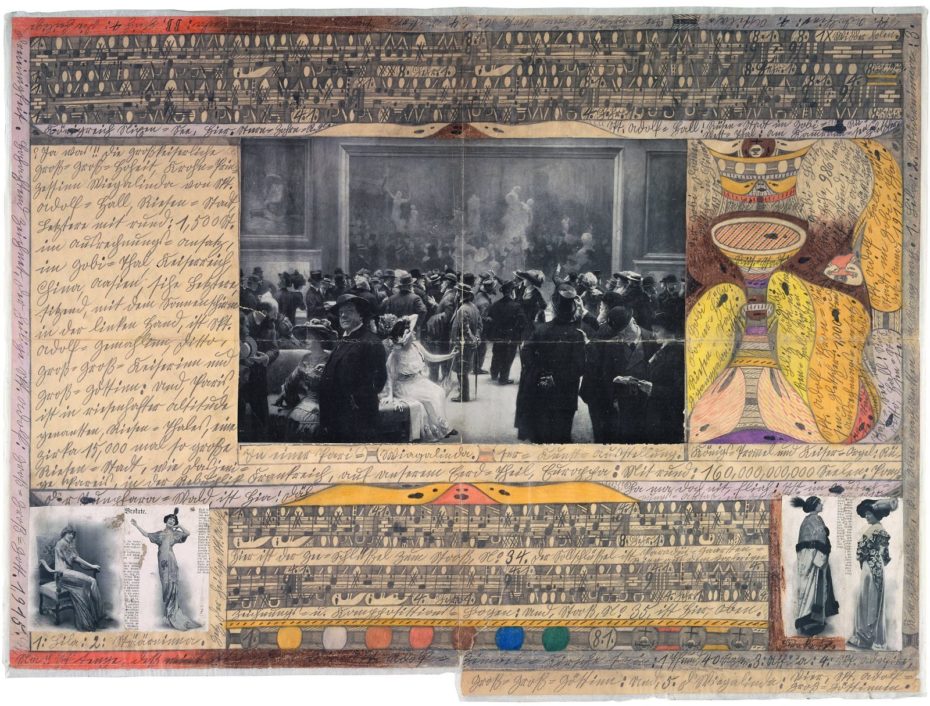

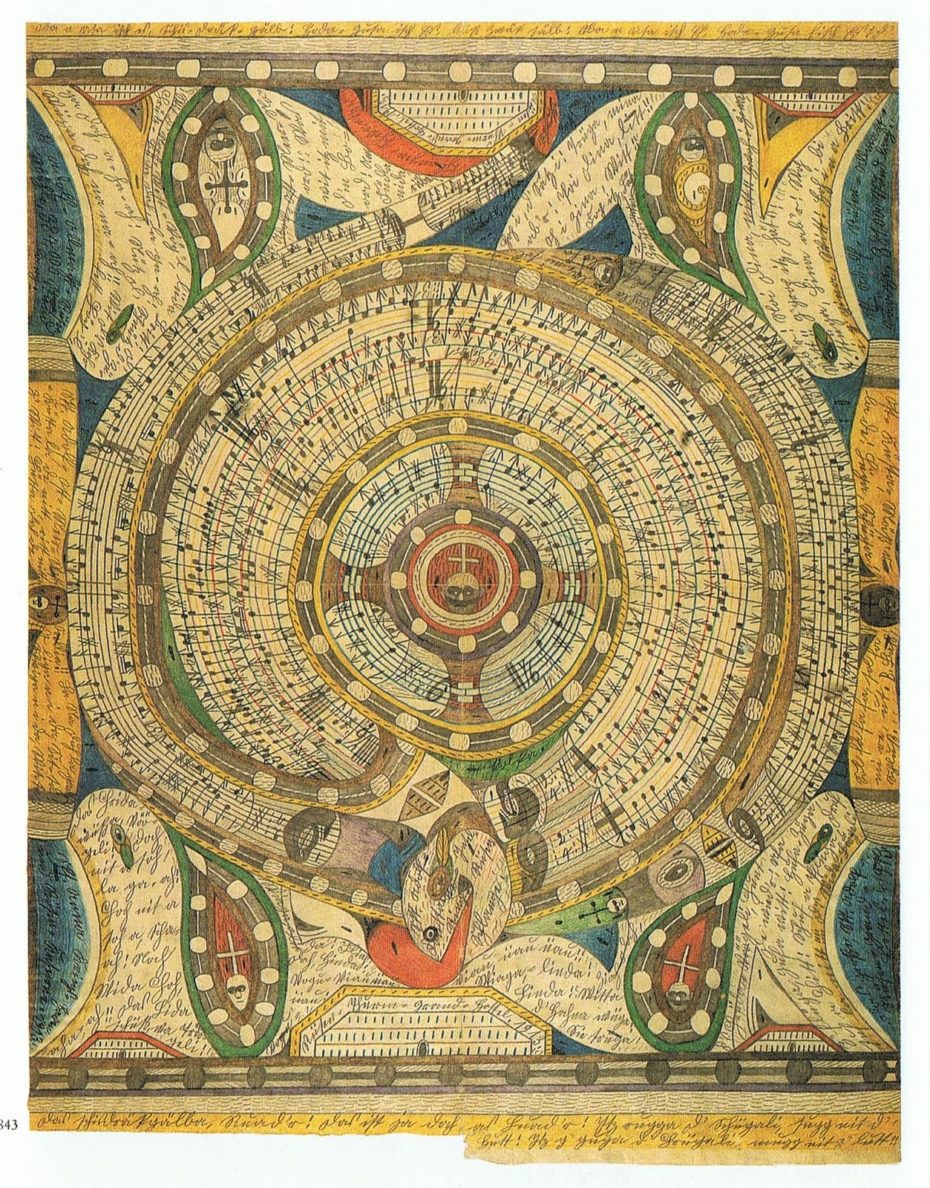

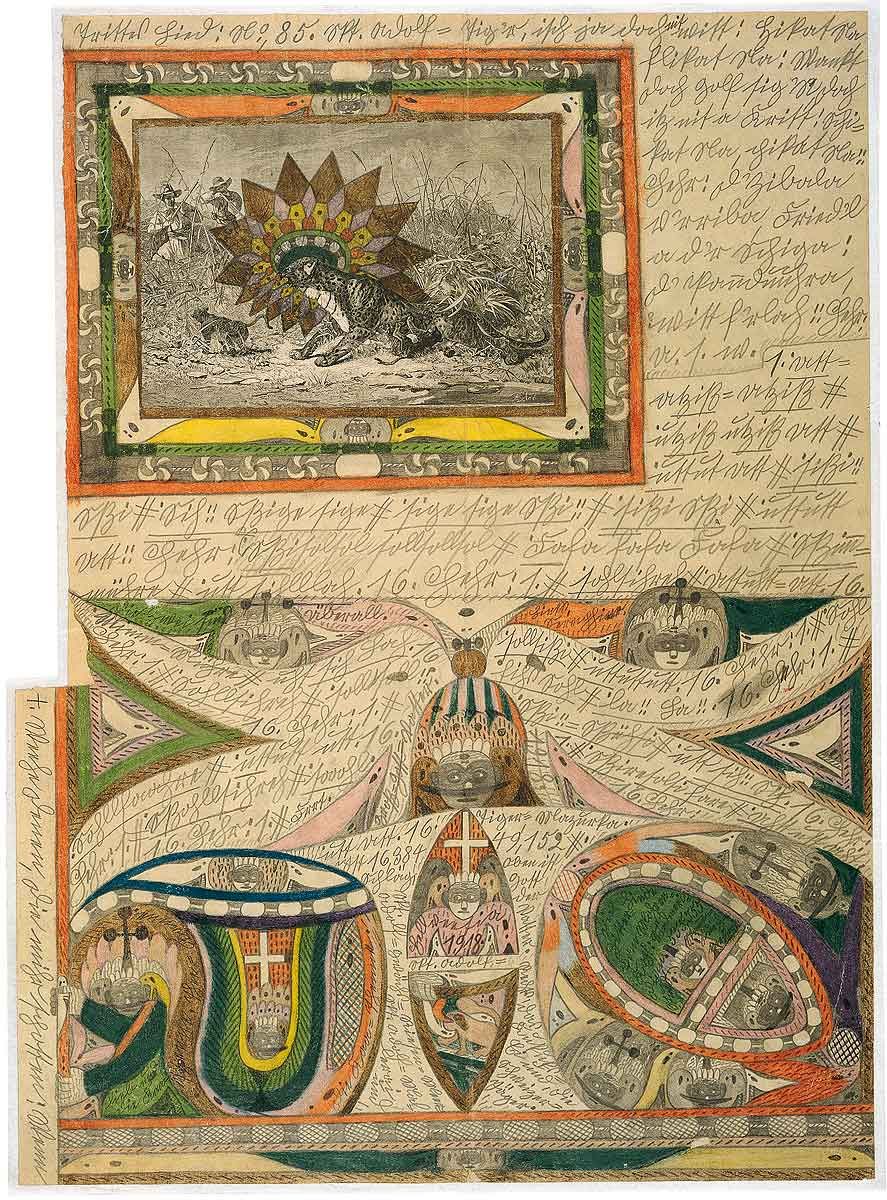

Some artists leave us tangled legacies– reputations tied up in creative theft, family feuds and unresolved estates. Others, like Adolf Wölfli, leave us a veritable Pandora’s Box for consideration. At a glance, Wölfli’s work oozes the sentiments of Psychedelic art; its kaleidoscopic swirls of colour look fresh off the Haight Ashbury, circa 1967. In truth, they’re the relics of a man orphaned in the 1800s, whose life was bookended by the abuse he both received and committed, and whose days were spent incarcerated at a Swiss mental hospital with schizophrenia. But that madness also incubated one of the most jaw-dropping works in Art Brut history: a 25,000-page, fictionalised autobiography filled with reptiles, knights, and dancing shadows; insect musicians, Algebra, and melancholic sheet music. Surrealist giant Andre Breton called it, “one of the three or four most important oeuvres of the twentieth century.” We call it a reminder that talent is not only transformative, but blind in picking its artist…

Wölfli was born a peasant in a village by Bern, Switzerland, in 1864, and orphaned by age nine. He worked long hours as a Verdingbub (indentured child labourer), where he was verbally and sexually abused, shuffled in-between foster homes, and traumatised into adulthood where he tried, in vain, to hold down a job as a mason and in the army.

By 26, he was in prison for two years on attempted child molestation charges, and by 31, he was imprisoned for life at Waldau Clinic in Bern, and diagnosed with one of the most intense cases of schizophrenia doctors had seen.

“He was first admitted to a general mental ward,” explains his doctor, Hugo Rast, in a 1971 BFI documentary, “but very soon it was found out that he was far too aggressive, violent…he couldn’t be left with other patients. He was suffering from hallucinations. He heard voices. He tore the ear off one patient. He bit the nose off another. I had to be very careful before entering his cell, and look through a peephole. I was always accompanied by five strong male nurses.”

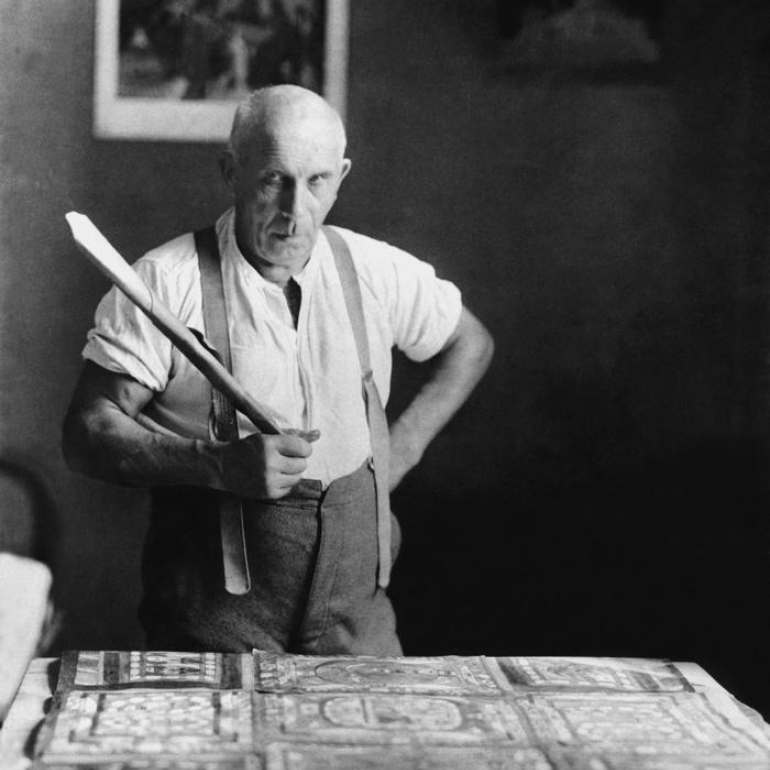

“When he started painting [our relationship] was much easier,” says Rast, “When I saw him screaming at the top of his lungs [he saw] my equipment was not a syringe. [It] was a piece of paper and a pencil. This disarmed him straight away.” Everything he could get his hands on turned to art. Even his dresser, which he filled with his writing…

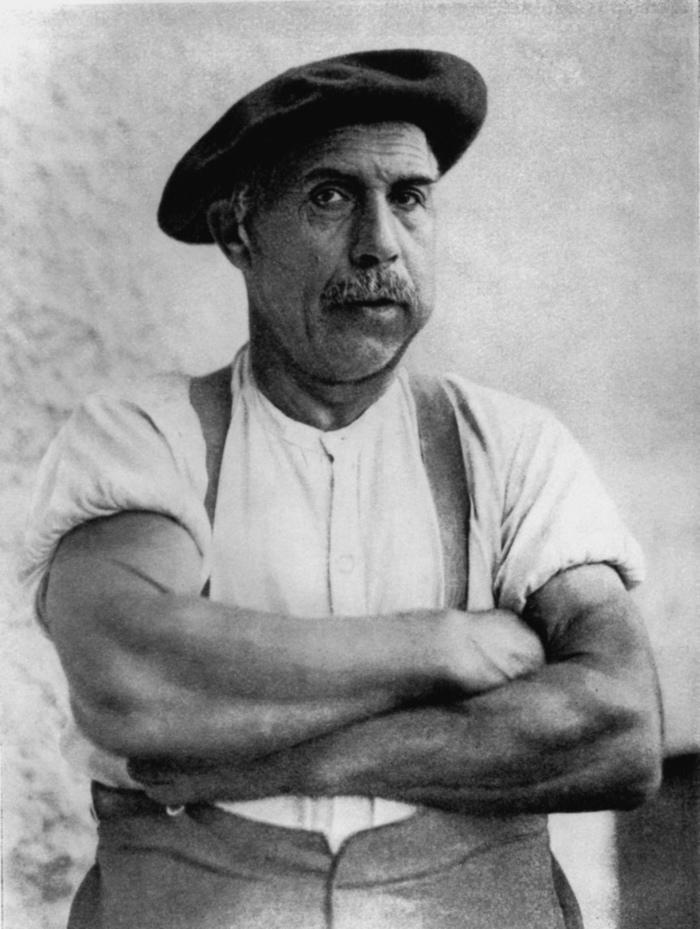

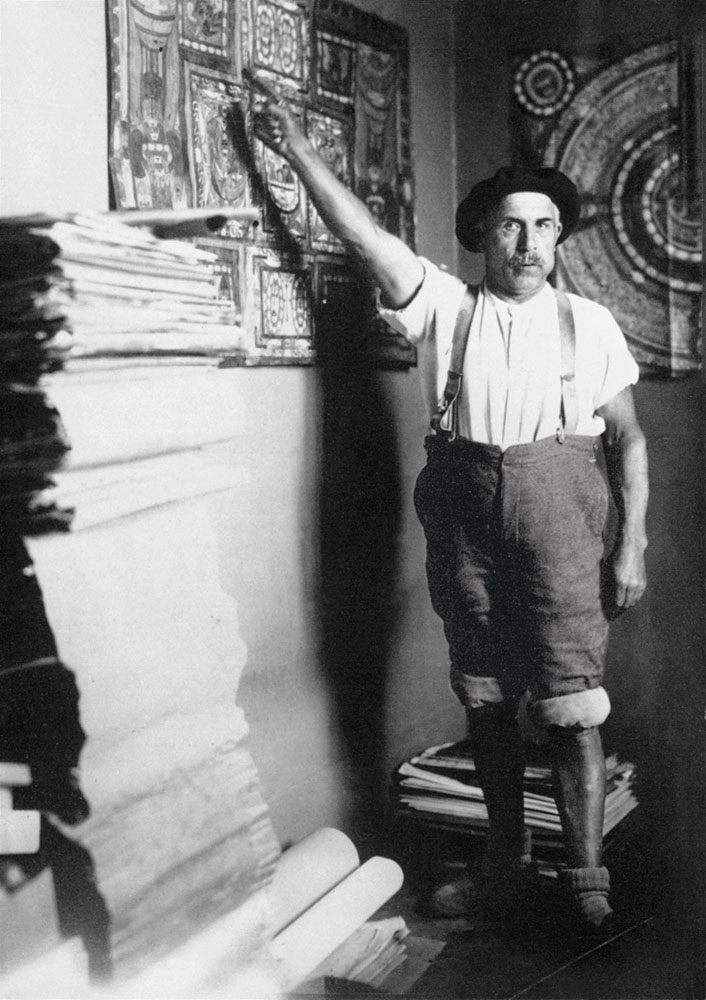

There is something so telling about Wölfli in the few images we still have of him: in one, he holds his tool like a sceptre. In another, he points to his painting like a captain in a crow’s nest. If you looked at his work, explains Rast, you entering his turf: a land where he was both “God and the Devil,” and signed his pieces, “Saint Adolf II.”

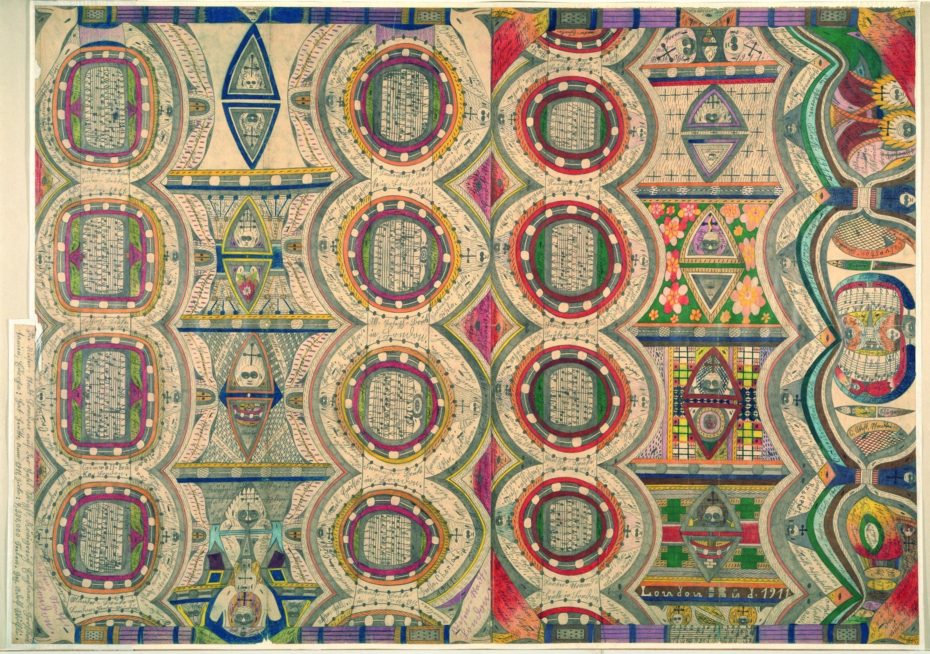

The Los Angeles’ Times’ Kristine McKenna points out how “suffocatingly dense [his work] is.” The effect is akin to looking either under a microscope, or down from an aeroplane. Symmetry, repetition, minutiae– as it turns out, are all common in works schizophrenic artists.

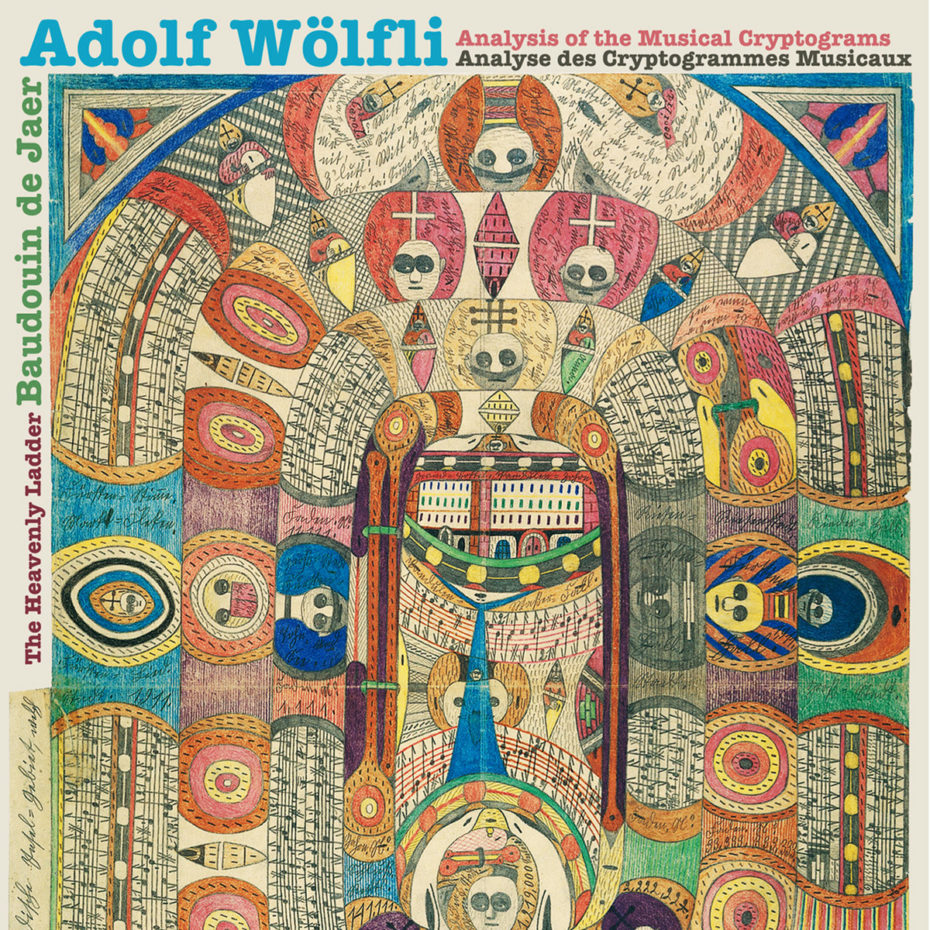

His hermetic works also began incorporating enigmatic, code-like musical cryptograms, which actually turned out to be real compositions which he would play on a paper trumpet. Composer, violonist, Baudouin de Jaer actually attempted to decode the artist’s scores, and released a recorded album called “Analysis Of The Musical Cryptograms / The Heavenly Ladder” as a result. You can listen to the music of Adolf Wölfli right here.

In 1921, psychologist Walter Morgenthaler published a landmark monograph on Wölfli titled A Mentally Ill Person as Artist – it was the first time someone looked at a patient not only as a person, but as a serious artist.

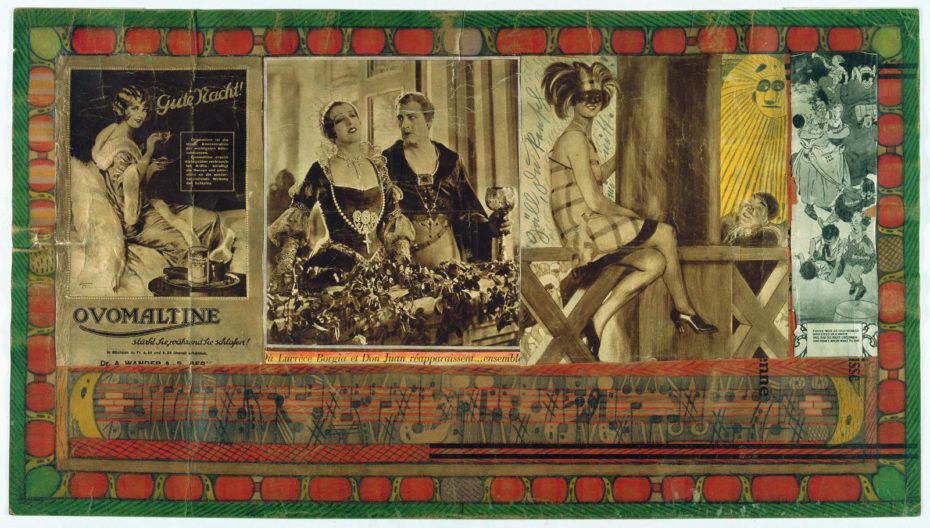

In the same vein of American outsider artist Henry Darger (a hermit-like janitor by day, art genius by night), Wölfli made narrative-driven collage works– but his pieces ran a shade darker than Darger. It was 25,000 pages of travelogues, drawings, and musical scores.

Before we discovered Darger, before Howard Finster, there was Swiss peasant Adolf Wölfli. Was he the most dangerous outsider artist or one of the most prolific? What was he trying to communicate? What are we not seeing in the art of the mentally ill that they are?

Wölfli’s life was the catalyst for a new conversation about not only mental illness, but the “job” of art in general. In its own broken way, he helps us tap into next-level empathy.

Learn more about his life and work on his website. We also recommend seeking out this movie on outsider art, featuring story of Wölfli.