A few words of advice: at a dinner party, always sit next to a snob instead of a bore if given the choice. Chances are, you’ll at least have a laugh. When decorating a room, always start with a rug; never over-dress, and, most of all, to get outta dodge, hit the road with the lot of The Rolling Stones. Such was the advice from ex-princess and American socialite extraordinaire, Lee Radziwell, who died last Friday in her Manhattan apartment at 85-yrs-old. As the younger sister of Jackie Kennedy Onassis, her life was nearly eclipsed by comparisons to her sister. But Lee was a force to be reckoned with in her own right, an impossibly chic woman who specialised in doing things she wasn’t supposed to: Divorce. Work. Party. Marry again (this time, a prince). Take polaroids with Andy Warhol. She was one of the saltiest, but somehow lovable “it-girls” in modern American history, so we’re raising a glass of bubbly to her with a walk down memory lane…

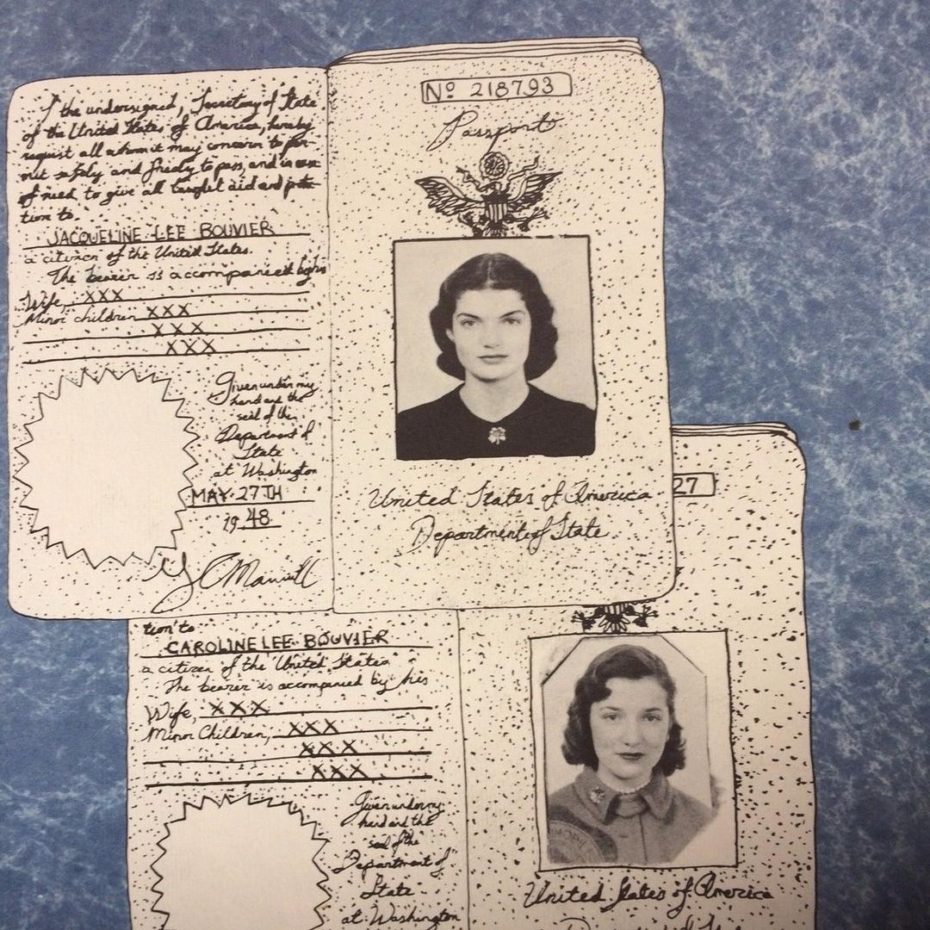

“‘I’m going to escape,’ [I thought], ‘I’m going to get out of here.’ [But] I realized I couldn’t go much further,” says Lee in one of her last video interviews with Time in 2013, perched in her perfect 5th Avenue apartment, with her perfectly coiffed beehive, while her friend Sofia Coppola (of course) asks a few (softly) pointed questions about her childhood. She was born Caroline Lee Bouvier to East Coast stockbroker John Vernou “Black Jack” Bouvier III, and fiery socialite Janet Norton Lee in 1933. Her upbringing was filled with distinguished schools like Ms. Porter’s Prep – which Lee later said she despised – and a lot of loneliness. So much, that a preteen Lee tried to run away with her dog, and her mother’s heels, across the Triborough Bridge. “I was so lonely,” she tells Sofia, “Of course when I got home I was punished. But the punishment wasn’t half as bad as when I tried to adopt an orphan.” Again, Lee goes off on a cinematic side-note: while her parents left her at home to “go deep-sea fishing in Chile,” she got terribly lonely. Jackie was at boarding school, and wanting a friend other than her nanny, Lee saved up her allowance, took a cab to the orphanage, and politely informed the mother superior that she would be adopting a new friend. That’s Lee’s life in a nutshell: Fabulous, but always a little heartbreaking.

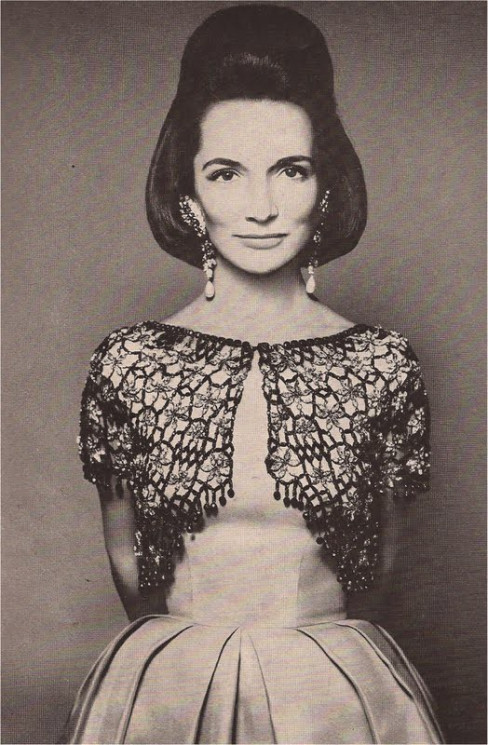

Lee Radziwill photographed for Vogue in 1962 © Cecil Beaton

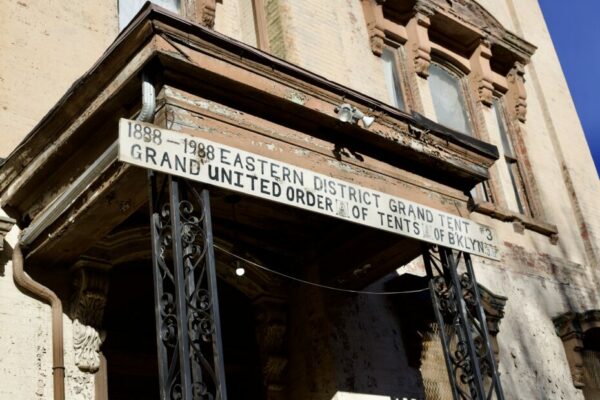

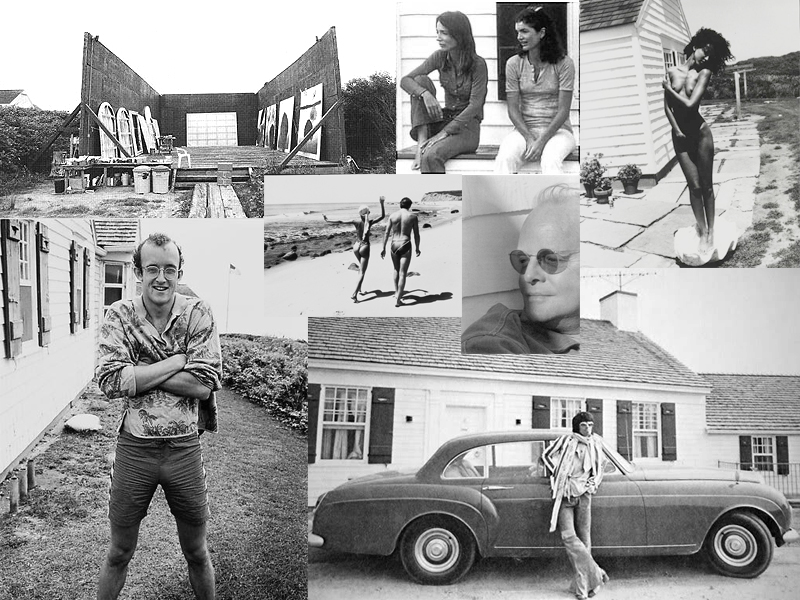

In Lee’s family matters, one also can’t leave out Big and Little Edie Beale of Grey Gardens fame. The mother-and-daughter duo of the cult documentary were Radziwill’s paternal aunt and cousin (respectively). And while Lee was not officially credited for the Grey Gardens film, the fact is, it wouldn’t have happened without her (whether she liked it or not). In the early 1970s, a film crew was hired to make a movie about Lee and her childhood in East Hamptons. It was Lee’s wish that her eccentric aunt would narrate the story, but it was nearly impossible to convince Big Edie to even open the door of her house, let alone participate in the project.

The original documentary crew, which Lee was funding, immediately shifted their interest from the Bouviers to the Beales once they discovered the two socialites-turned-hoarders living in a strange old mansion filled with cats. According to one of the directors, Radziwill withdrew her funding when she realised the crew wanted to make a movie about her reclusive relatives instead. But without Lee’s initial idea to work with the Beales, without her persistence to drive up to Montauk and knock on their door every day, it never would have happened. The movie took an unexpected turn for the better when Lee made that introduction, but the original footage for Lee’s documentary was shelved and the footage went unused. In 2018, Radziwill released a documentary with some of the footage called That Summer.

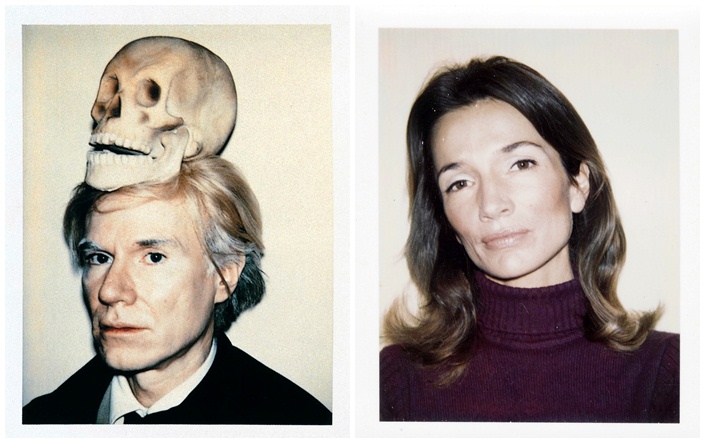

By the 1950s, Lee had already made a name for herself amongst the fashion set. She worked as Diana Vreeland’s assistant at Harper’s Bazaar, and her nonchalant air and quick wit made her one of Truman Capote’s society swans.

“She’s a remarkable girl,” he told People in the 1970s, “She’s all the things people give Jackie credit for. All the looks, style, taste—Jackie never had them at all, and yet it was Lee who lived in the shadow of this super-something person.”

Her looks were cool, crisp and confident, and throughout the years she inspired everyone from Yves Saint Laurent, to Marc Jacobs; she became a staple on the Studio 54 scene, at Andy Warhol’s factory, and hung out with him and all the cool kids at the beach in Montauk.

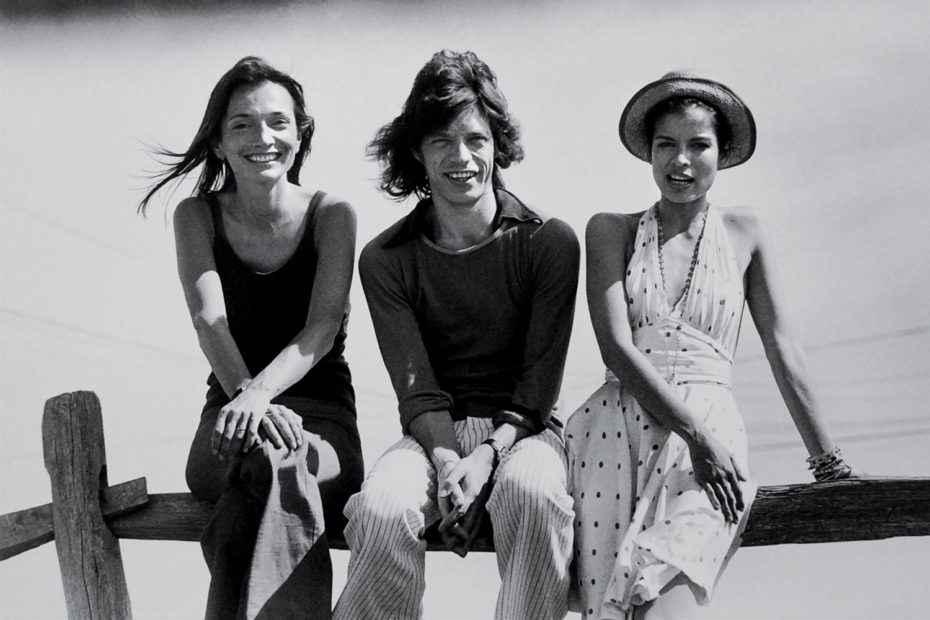

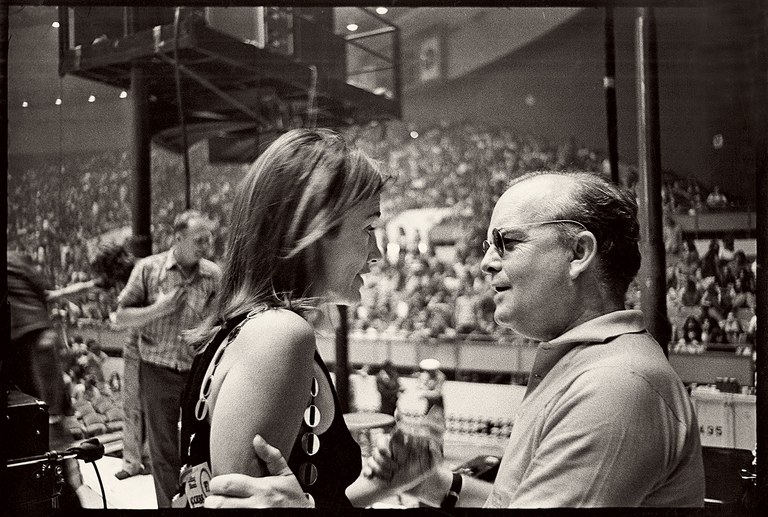

“Rolling Stone magazine had asked Truman [Capote] if he would write about their tour,” she told Sofia about the time she spent with Capote and The Rolling Stones in 1972, “He was thrilled, delighted. And so he said [to me], ‘Honey, you gotta come.’ I said, ‘I would adore to. That’s how it started. I can’t remember how many cities I went to.’” She slept on the tour bus, in the bunk beds, and didn’t go weak in the knees for Mick Jagger. “[He was] the way you’d expect him to be. I can see how people found him sexy,” she says, and then, half-joking, “But I found him a little repulsive.” Apparently, The Stones’ feeling was mutual. Keith Richards called her, “Princess Radish.”

“The most important thing, I’ve found, is to be self-reliant,” she told The New York Times’ Judy Klemesrud in 1974, when the media scratched its head as to why a society girl would want to sleep in bunk-beds on the road, or get to work. She acted, and wrote. She didn’t have much success at either, but to her credit, it must’ve been incredibly difficult to explore new passions under the media’s magnifying glass and comparisons with her sister. “It is difficult for someone raised in my world to learn to express emotion,” she once said about her acting aspirations, “We are taught early to hide our feelings publicly.”

She also did PR for Armani, opened an interior design office, and started a talk-show with guests (who were all friends) like Gloria Steinem, the designer Halston, even the reclusive soviet dancer Rudolf Nureyev. “If I really can be said to have a personal style, I think it is reflected in my taste for the exotic and the unexpected” she said, “[…] then add touches of the bizarre and the delicious.” She was simply insatiable, and inexhaustible when it came to putting her taste to the test.

And as for men, and matters of the heart? There was the artist Peter Beard, who introduced her to the New York art scene. Then there was her first husband, Michael Canfield, the illegitimate son of England’s royal duke of Kent, and Stanislas Radziwill, her second husband and a Polish prince, and finally, Herbert Ross, the American film producer who she divorced not long before his death. Of course, the narrative that swallowed up most of Lee’s legacy was her relationship, and purported rivalry, with Jackie.

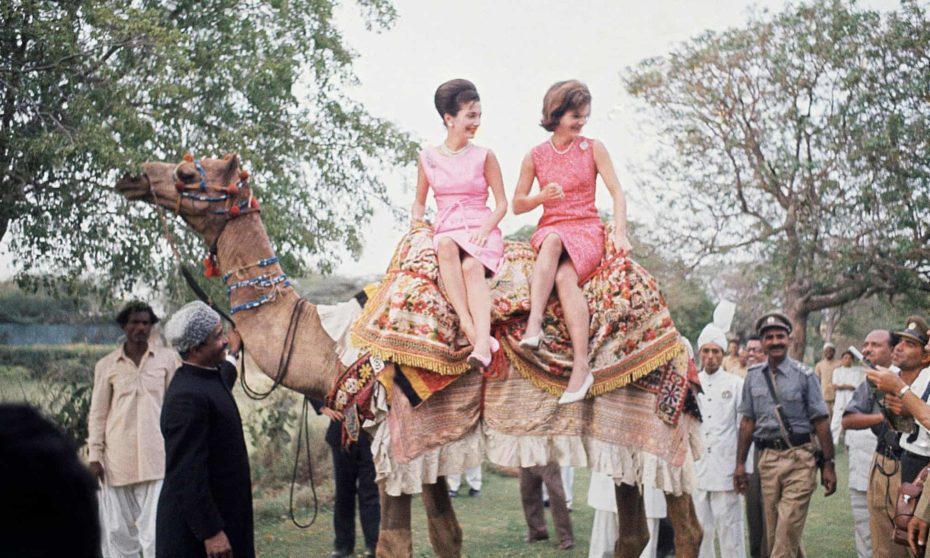

Jackie was the family favourite, and a straight-A student. Lee was the black sheep who left university to go explore Italy. Jackie bagged a President, but Lee bagged a Prince (her second of three marriages) – and so on. Think of them as America’s answer to Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret.

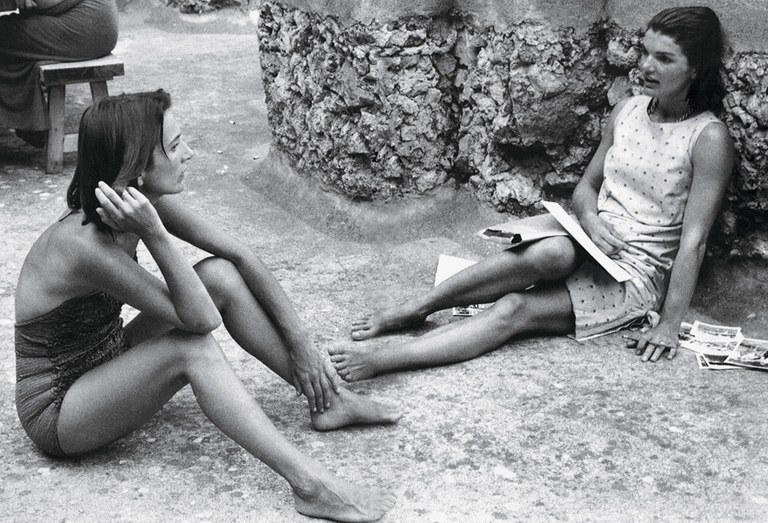

It was terribly easy for the tabloids to poke and prod at their competitiveness, even if the sisters brushed it off. In the 1950s, they vacationed across Europe together, in escapades they later published as One Special Summer, a kind of public scrapbook and testimony of their solidarity.

Jackie, for one, never quite recovered from the trauma of her husband’s death. At that same time, she also hit it off with Lee’s not so under-cover lover of over five years, Aristotle Onassis. As the story goes, Lee invited Jackie on Onassis’ yacht, and her sister “co-opted Onassis on that cruise,” according to Lee’s biographer Diana Dubois in In Her Sister’s Shadow: An Intimate Biography of Lee Radziwill. “Making things even more complex,” adds another biographer, J. Randy Taraborrelli, Jackie decided not to discuss Onassis’s proposal with either [her mother] Janet or Lee. The secrets and lies of omission just kept stacking up among the three women.”

Lee was the matron of honour at their eventual wedding in 1968, and the press said it rang in a new ice age between the sisters. But there’s a camp of historians that sees things differently. One that acknowledges the girls’ difficult relationship, but sees Lee as a quiet protector of a broken sister who looked to Onassis for comfort and protection at a time when she felt vulnerable. It cost Lee her pride, maybe even her love, but it meant some kind of happiness for Jackie.

Lee’s legacy is the kind that can’t be easily deduced. Rather, she was one of those remarkable folks for whom living is itself an art – something more relevant than ever in the era of Instagram, reality TV, etc. Giorgio Armani told WWD once, “When I met her […] I had the impression that she represented a very contemporary irony about American aristocracy, which is almost impossible to define. It is one that combined ease and sophistication, spontaneity and respect for the rules.” It is, as they say, the ineffable “It Factor.”