Somewhere in between a business card and a message in a bottle, here’s a concept to boggle the millennial’s mind. Long before we were friend requesting on Facebook, following influencers on Instagram and instantly communicating with strangers around the world by simply typing in their social media handles – there was the radio calling card… aka the QSL card.

Once upon a time, amateur radio and citizens band hobbyists used the postal system to send out personalised cards that gave out their frequency, location and other bits of information about themselves, in the hopes of connecting with other users. As far back as the 1920s, folks began trading and collecting personalised QSL cards to find broadcasters and listeners – in the same way that we might seek followers today to subscribe to our daily musings on Instagram. The golden age of the QSL card may have come and gone, but this early form of social media shows just how far we were once willing to go to contact one another…

As a radio operator, when you’re able to pull in a distant, faraway station, it’s a proud moment. When that other station comes crackling through on the radio receiver from hundreds or thousands of miles away – you are pumped, and you want to let the other person know you can hear them. And that’s where QSL cards come in.

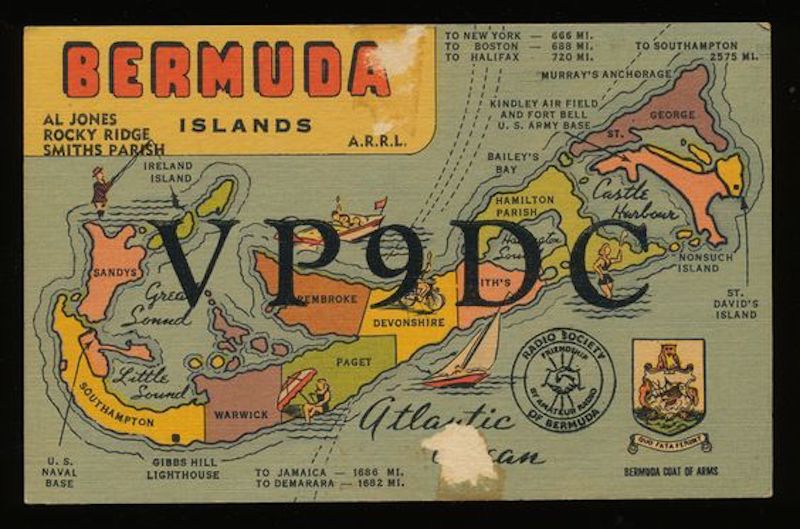

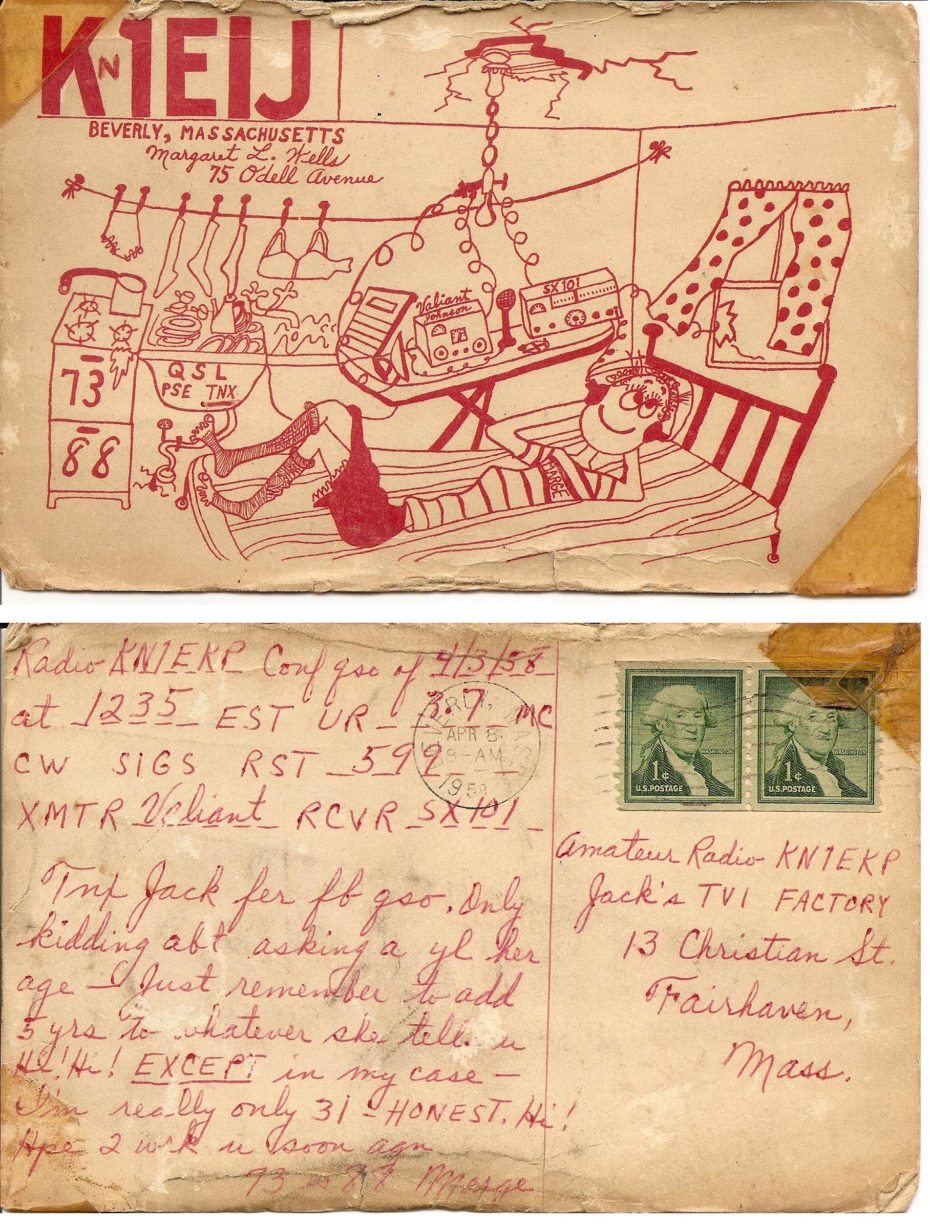

In the earliest days of radio broadcasting, amateur enthusiasts came up with the idea to send letters out to let radio stations know that they could be heard from far away, how good the signal was and to give their location in return. As this practice became more popular, the letters came to resemble customised postcards, and the QSL card war born. Both ham radio and citizens band hobbyists (you can learn the difference between the two here) began mailing them out all over the world, depending on how far they could reach, as confirmation of communication between them.

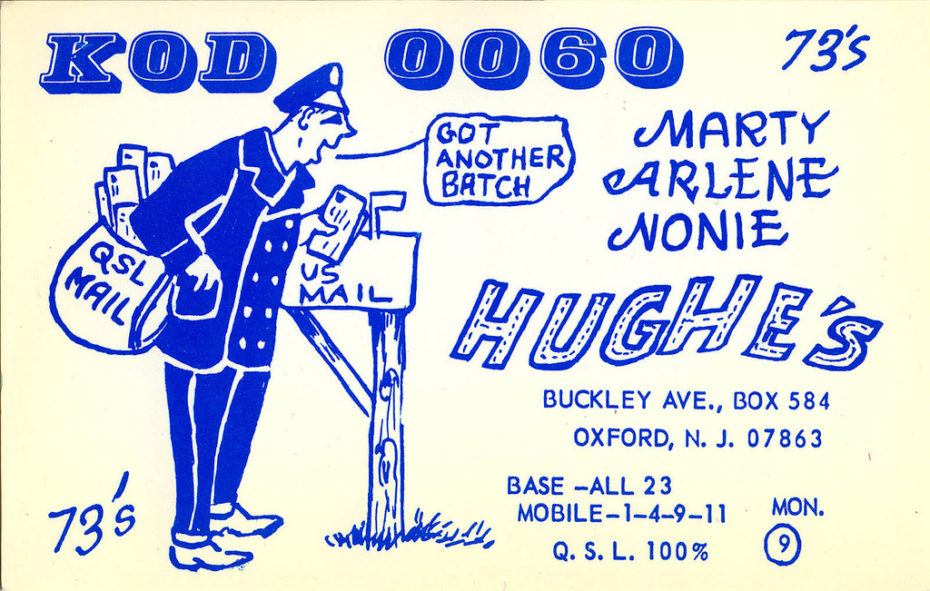

The QSL card derives its name from the Q code, a standardised collection of three-letter codes created when radio used Morse code exclusively, which was later adopted by amateur radio operators. QSL literally stands for: “I confirm receipt of your transmission”, in other words– I hear you. If you send out QSL cards with a question mark, it means: “Do you confirm receipt of my transmission?” Think of it like the old-school version of a Facebook friend request.

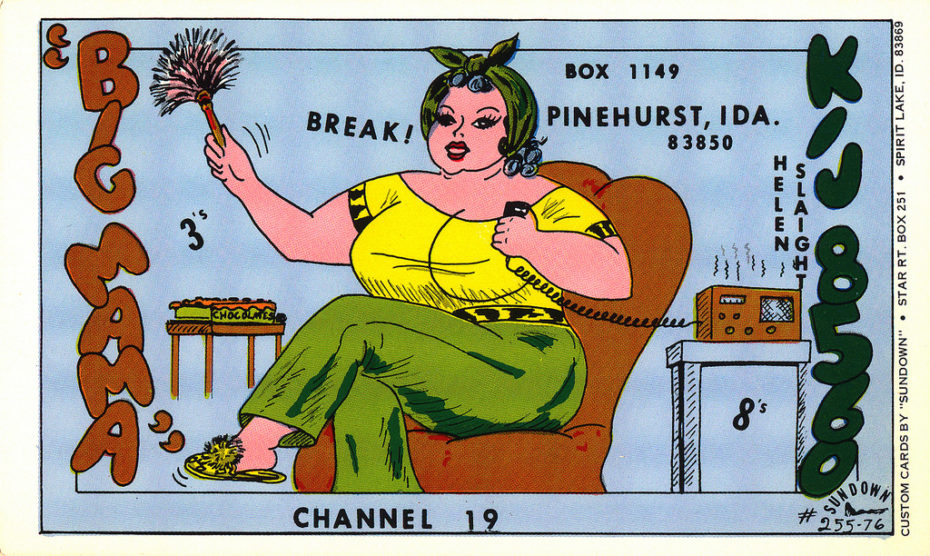

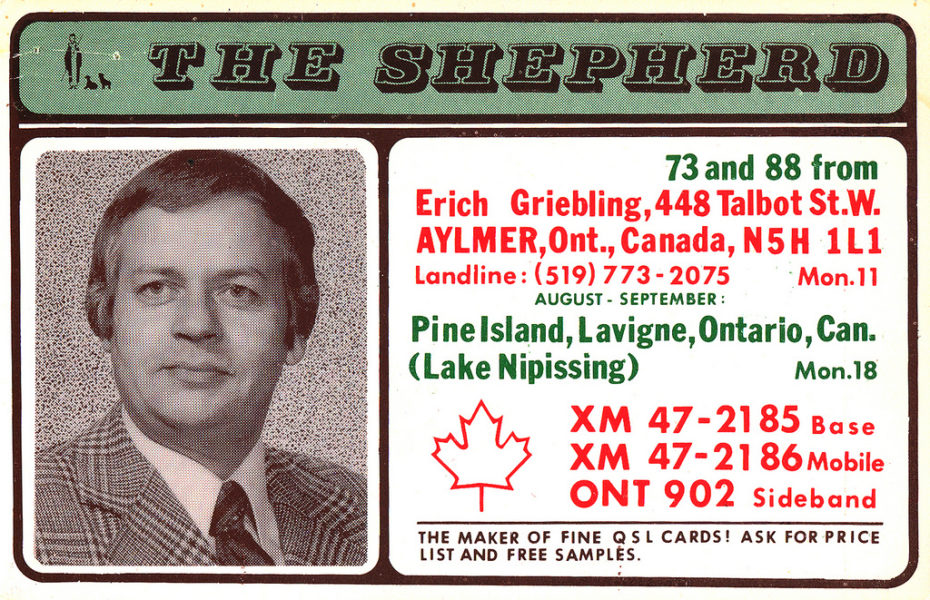

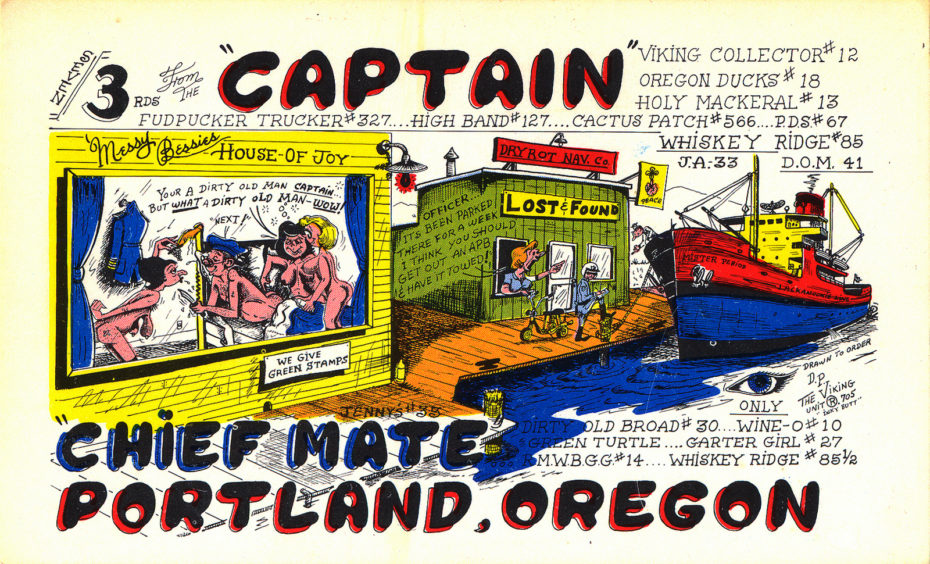

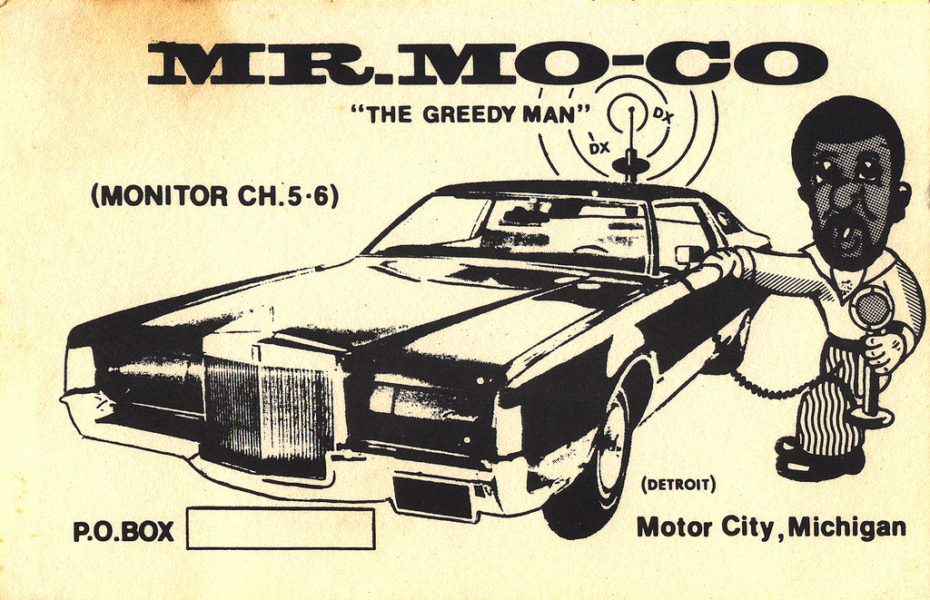

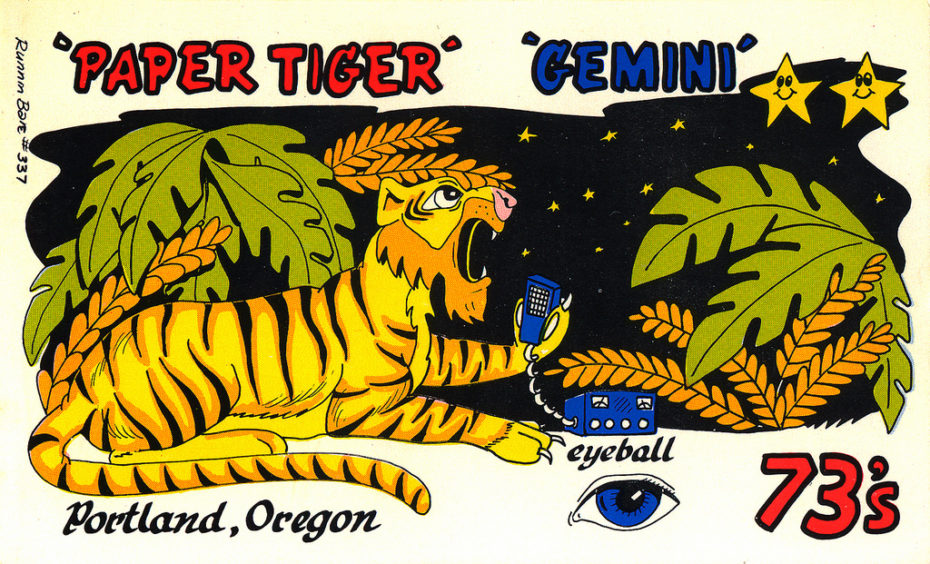

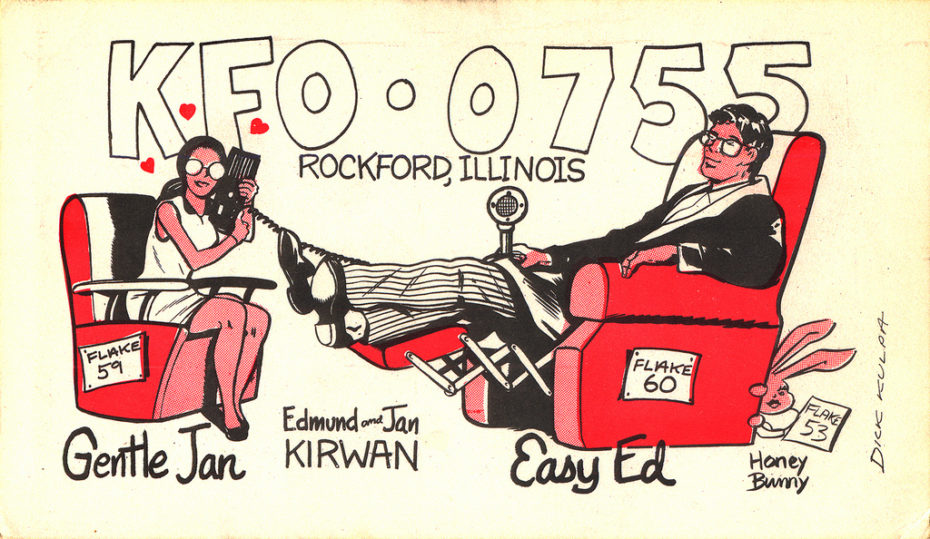

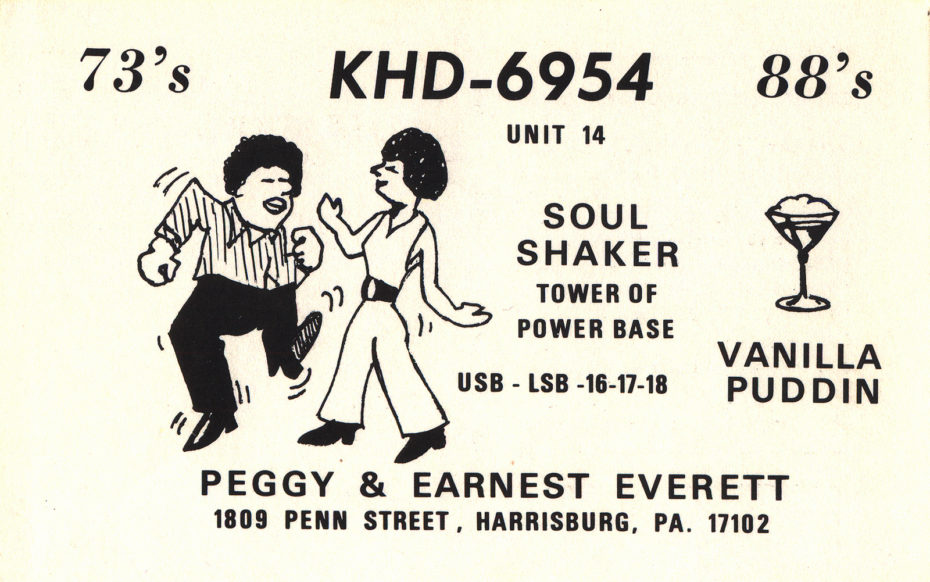

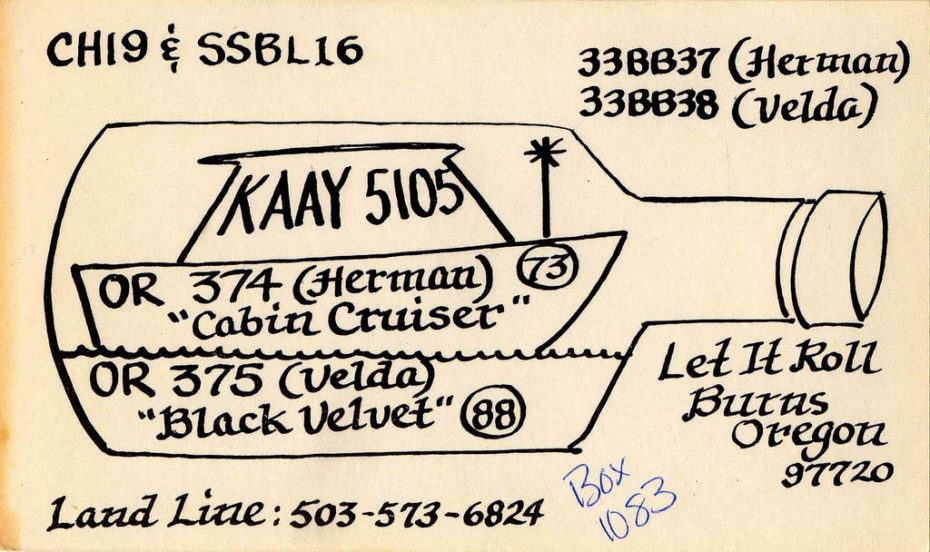

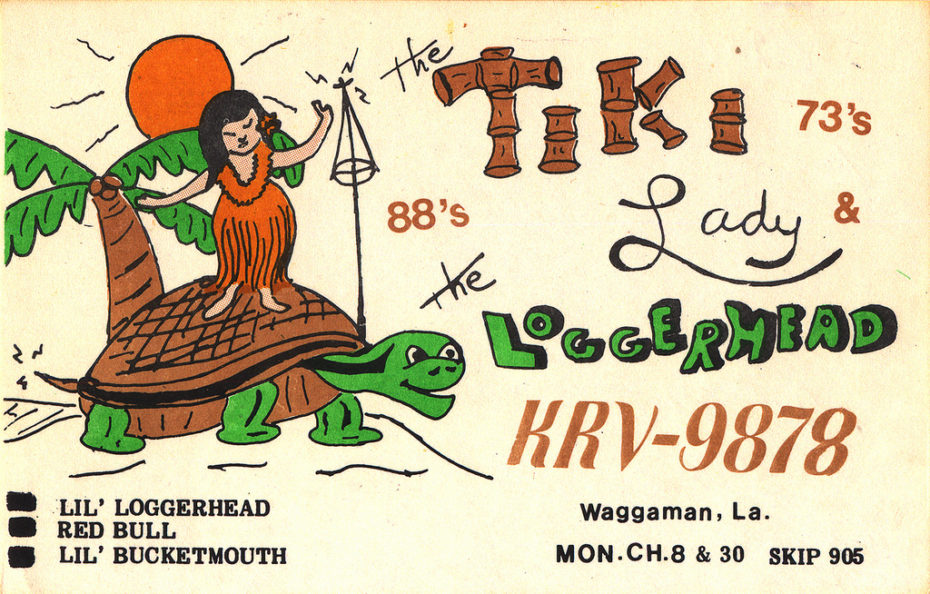

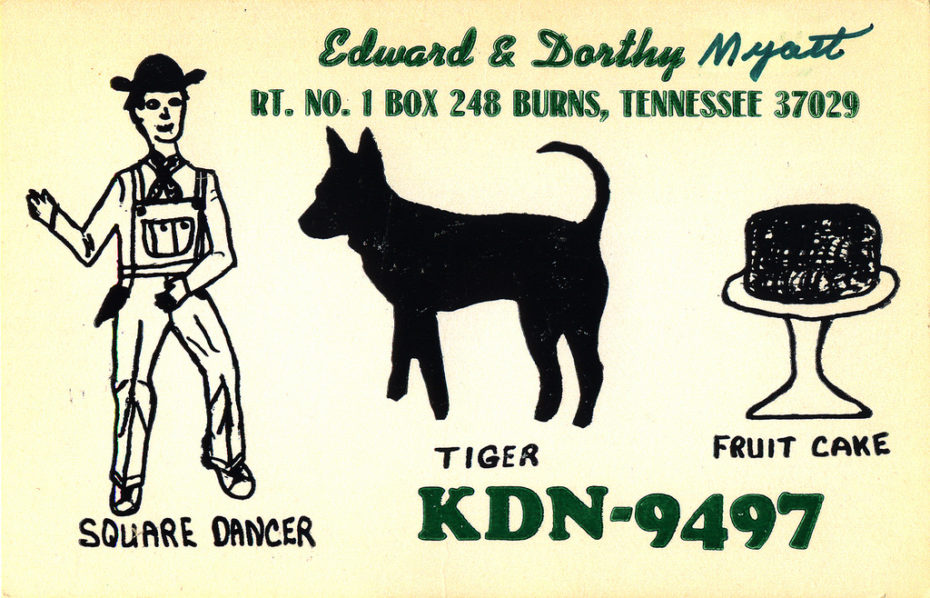

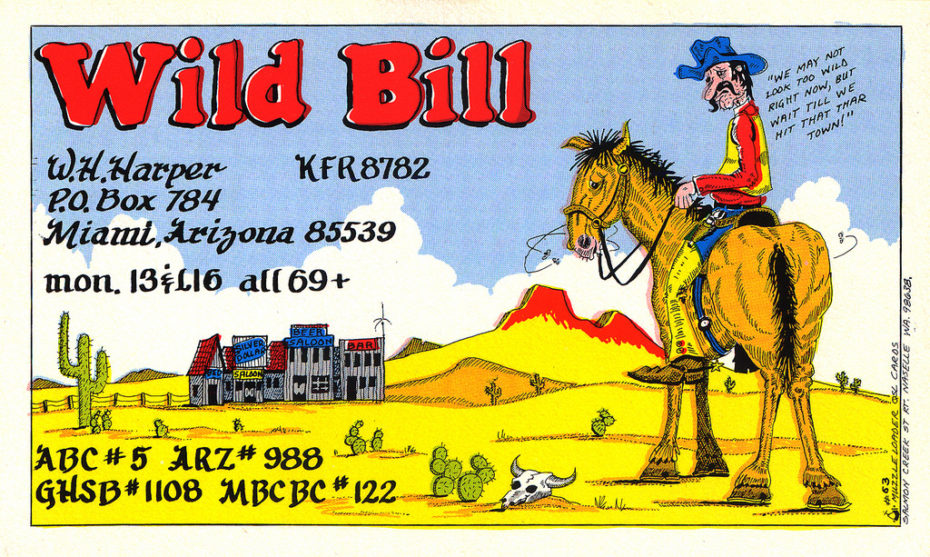

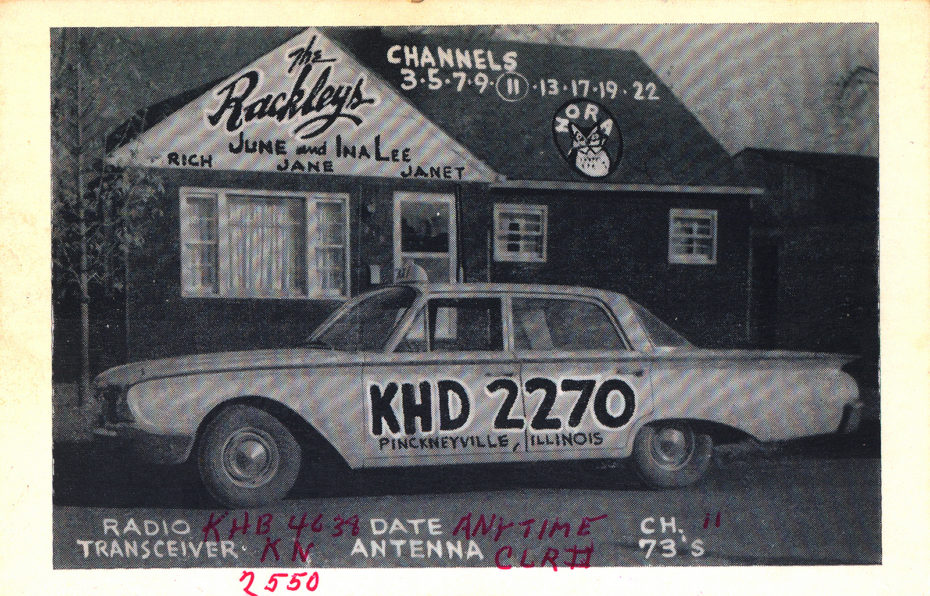

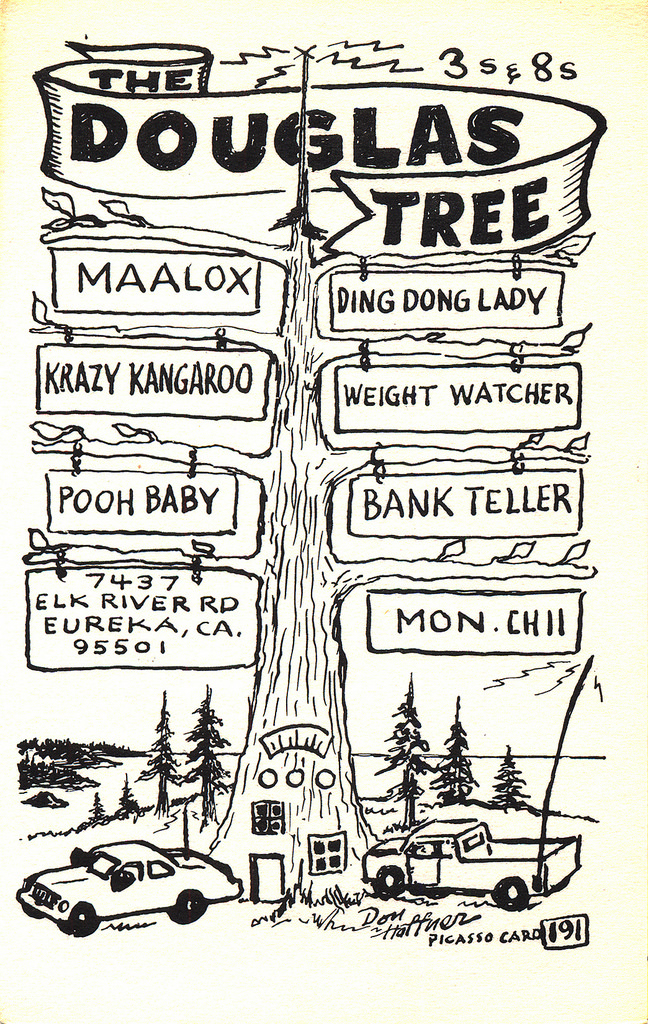

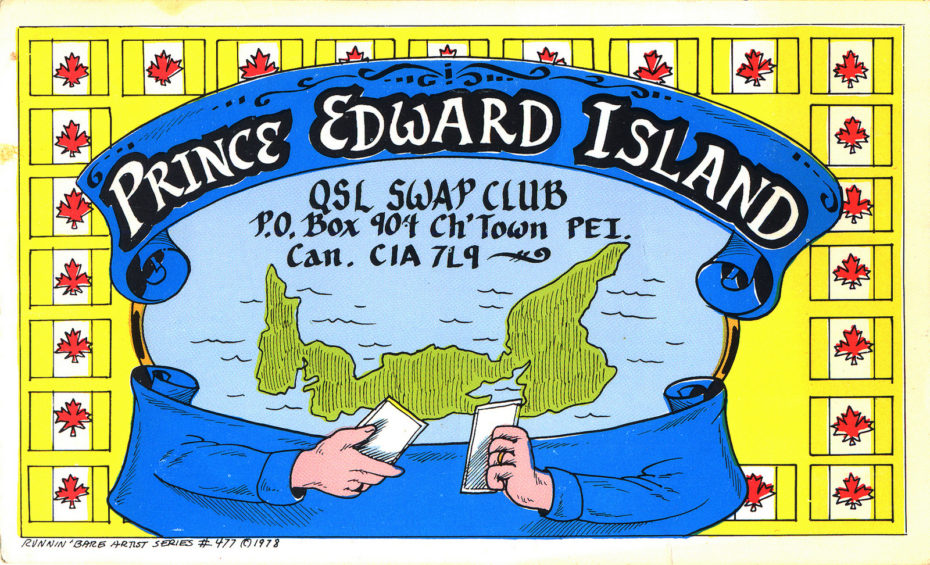

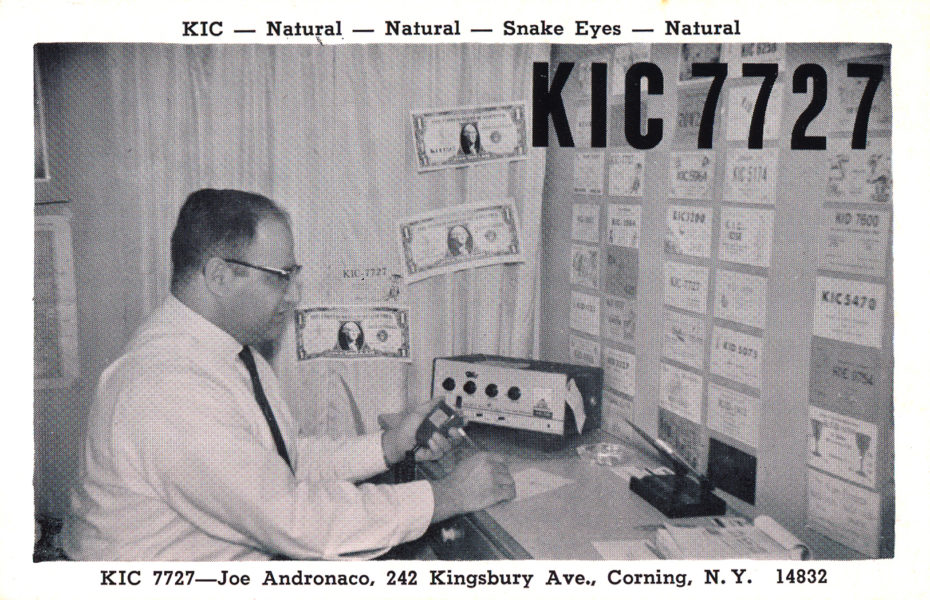

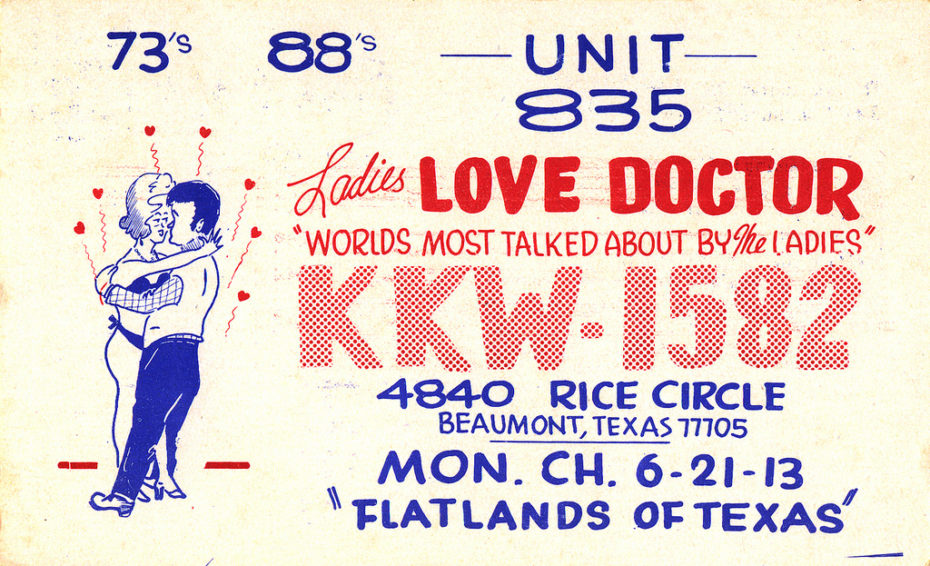

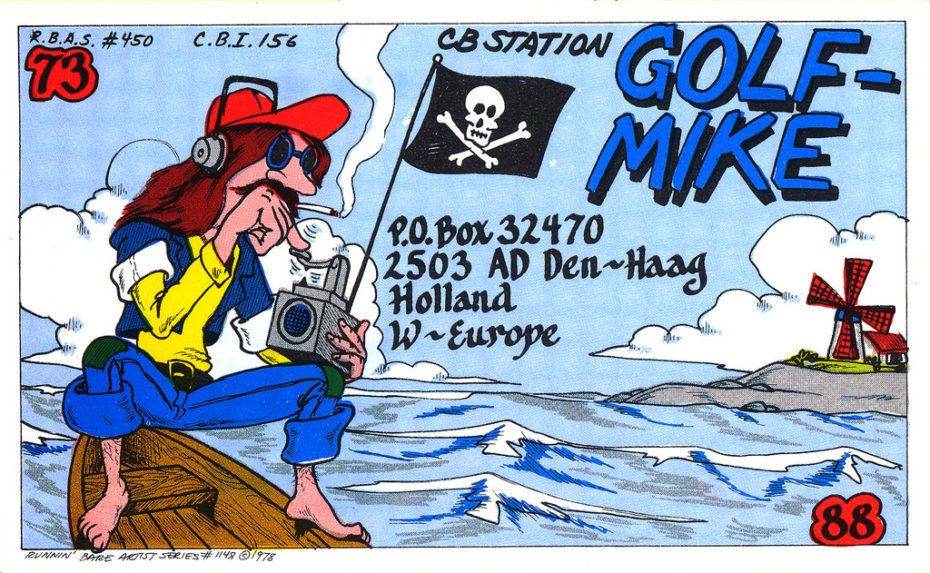

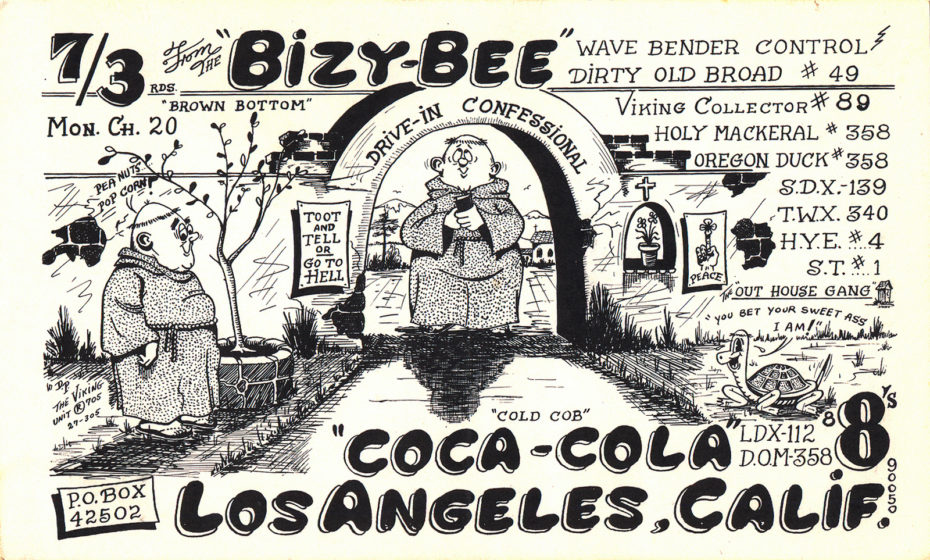

Traditionally sent using domestic or international postal systems, QSL cards can be posted either directly to a radio user’s address or you can send a batch of cards to a country’s centralised amateur radio association QSL bureau, which distributes cards for that country. The heyday for QSL cards reached its peak in the 1970s, when the cards expressed one’s individual creativity, not unlike how we personalise our Facebook profiles or share snapshots of our lives on Instagram to let the world know who we are. While most people made their own cards, for the most dedicated operators, hiring local artists to design QSL cards also became popular practice too, especially for citizens band radio.

Radio enthusiasts around the world began collecting QSL cards, treasuring the most unique and long distance ones. There are countless archives now on the internet; rare QSL cards for sale on eBay, vintage QSL artwork organised on Pinterest boards, crowdsourced in Flickr albums, proudly shared in chat forums – and then there are the people who just aren’t sure what to do with their father’s old collection of QSL cards they found inside a dusty box at the back of a closet.

Because thanks to the internet, you can now find systems online that store all the same information normally verified by QSL cards in an electric format. And just like that, quirky QSL cards became a lost art.

As I was looking through the internet’s extensive archives of forgotten QSL cards – some extremely lovely to look at (and some strangers than others), I couldn’t help but wonder– what kind of a person is an amateur or CB radio user?

Well, it turns out Marlon Brando was an expert Ham radio operator and would often times have conversations with unknowing boat captains as they’d pass by his island in the French Polynesia. First Lady, Betty Ford, used the handle “First Mama”. The International Space Station also operates a Ham radio station and it’s possible for other amateur radio users to call the ISS if it’s passing above your area and even get a response from an off-duty astronaut. If you manage to connect with the busy station, they’ll even send you a QSL card. And then I learned of a 9 year-old girl from Florida called Hope Lea who sends out QSL cards to confirm receipt of another station’s transmission. It might seem like an archaic hobby to some, but if one day our Wi-Fi dependent world as we know it comes to a crashing halt, it’s people like Hope, with her trusty radio and collection of hand-written QSL codes that will be leading the way.