It’s 1945, and US Airforce pilot James Gaussman is just trying to focus. He’s flying a leg of his journey between India and China, when suddenly, a glimmer catches his eye. Emerging from the plains of China’s heartland, he spots it: a tremendous pyramid that would put Giza’s to shame. “It was pure white on all sides,” he said, “The remarkable thing was the capstone, a huge piece of jewel-like material that could have been crystal. There was no way we could have landed, although we wanted to. We were struck by the immensity of the thing.” Two years later, Colonel Maurice Sheahan, the Far Eastern director for Trans World Airline, reports the same experience. This time, The New York Times runs his story, and the world is fascinated with what could be one of the biggest finds in archaeological history. But was the 1000-ft pyramid actually real? And if so, had anyone dared go inside? Fast forward half-a-century, and the answer is definitely clearer – but not crystal.

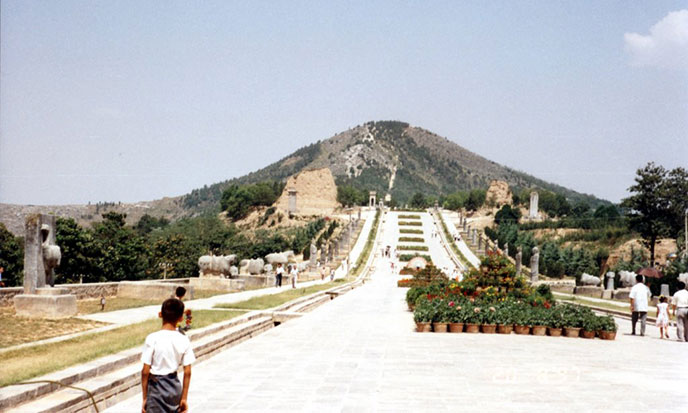

James Gaussman’s photo of the storied “White Pyramid”

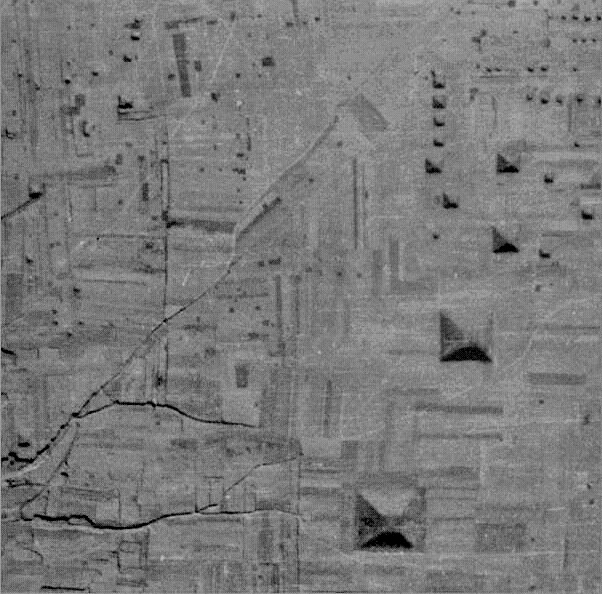

Today, Google Earth will show anyone with the right coordinates evidence of not just one, but several pyramids in Xi’an, in the Shaanxi Province of north-western China. There are nearly 40 known pyramids, but not all are easily distinguishable to the human eye; they’re covered with trees and grass, and many date back 8,000 years. They’re also not quite pyramids, but more like giant, flat-topped burial mounds for ancient emperors – in that way, they almost have more in common with the Mesoamerican pyramids. But the region is, in essence, China’s version of both Giza and the Valley of the Kings, particularly because there’s a whole lot of royalty hiding under that dirt that no one has dared disturb.

First, let’s play “spot the pyramid” and see if our grand white pyramid, storied to be 20 times the volume of the Great Pyramid of Giza, actually exists; a few pyramids are visible, but no traces of a gem poking out the top…

As early as the 17th century, a Roman Jesuit wrote about the pyramids, and in 1785, the French orientalist and sinologist Joseph de Guignes wrote, An Essay in Which We Prove The Chinese Are an Egyptian Colony.

As academic Thiks Weststeijn explains, “both used hieroglyphics to hide their secret wisdom; Egyptians and Chinese both venerated tradition; they were avid practitioners of science, in particular astronomy; and they believed in the transmigration of souls […] how could it not be that those monuments of mankind, the Pyramids and the Great Wall, had been built by the same people?” As we know, they weren’t. But that didn’t matter. For centuries the pyramids slept in undetected peace, until the dawn of the 20th century (and its technology) shook things up.

“The Chinese pyramids of that region are built of mud and dirt and are more like mounds than the pyramids of Egypt,” reported the Science News Letter in 1947, “[but] the region is little travelled. American scientists who have been in the area suggest that the height of 1,000 feet (300 m), more than twice as high as any of the Egyptian pyramids, may have been exaggerated, because most of the Chinese mounds of that area are built relatively low. The location is in an area of great archaeological importance, but few of the pyramids have ever been explored.”

Now, don’t forget: when we talk about the Chinese pyramids, we’re only talking about the information that has been made available by a rather tight-lipped Chinese government. Western archaeologists have, to this day, rarely been permitted to investigate the sites. What’s more, they appear overgrown by shrubs and abandoned – at first glance.

In the handful of photos we have of the pyramids, the shrubs are clearly deliberately planted. Methodically, even: many are cypress, one of the fastest growing trees out there.

What could they be covering up? Almost certainly emperors, and even their afterlife companions (and not just their spouses). Horses, for example, were very revered in Ancient China and massive “Horse Burials” were practiced across Asia and many Indo-European countries. The tomb of Duke Jing of Qi (547-490 BCE) contained over 600 horses:

Mass horse burial for Duke Jing of Qi (reigned 547–490 BCE. Wikimedia Commons.

Unearthing hundreds of “sacred beasts” would be impressive enough, but in 1974, the world got a peek of a truly next-level discovery. Two farmers were digging just outside Xi’an in March, 1974, when they discovered the famous terracotta army of the China’s First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang…

There were legends he’d been buried inside a veritable mini city with palaces, carriages, treasures, and anything else he’d need in the afterlife – and through luck, or fate, these farmers hit the jackpot.

The site is so massive, researchers are “going to be digging there for centuries,” archaeologist Kristin Romey told Live Science in 2012.

You see, even the Emperor himself hasn’t even been discovered yet. Or if he has, officials are too afraid to go near him; legend also tells of the Emperor being surrounded by a tunnel of 100 man-made, mercury filled rivers. It’s also said those who knew where the tomb was, were killed to keep it a secret during its construction, and long after. Hence, the ghostly soldier army: this isn’t a place that wants visitors.

So in matters of understanding these pyramid-mausoleums, Emperor Qin’s is just the tip of the iceberg. Some of the pyramid sites, like the Han Yang Ling Mausoleum, have been opened for tourism – but no one is unearthing them anytime soon.

Why? For one, the Chinese government says the technology just doesn’t exist yet to excavate the pyramids without damaging its contents. “It’s really smart what [they’re] doing,” archaeologist Romey said, citing the rushed excavation of King Tut’s tomb as a reason to pump the brakes. “Think about all the information we lost just based on the excavation techniques of the 1930s. There’s so much additional [information] that we could have learned, but the techniques back then weren’t what we have now. Even though we may think we have great archaeological excavation techniques [at present], who knows, a century down the road if we open this tomb [they could be even better].”

Giuseppe Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Pyramid in the distance

Why the government deliberately covers the pyramids, however, is something our scholar Weststeijn might’ve solved. Chinese culture’s strong “veneration of tradition” could mean they simply wish to leave their royalty at peace, which means we’ll have no choice but to watch them recede back into the earth with their secrets – until someone decides otherwise. In the meantime, Indiana Jones and the White Pyramid has a nice ring to it, no?