Show me an Instagram filter that can do this and I’ll personally take you out to dinner so that we can become lifelong friends. Autochrome is a dead art – a secret recipe – if you will, that has been long lost to the modern world, left uncharted by 21st century technology and yet to be truly explored or recreated for the digital age…

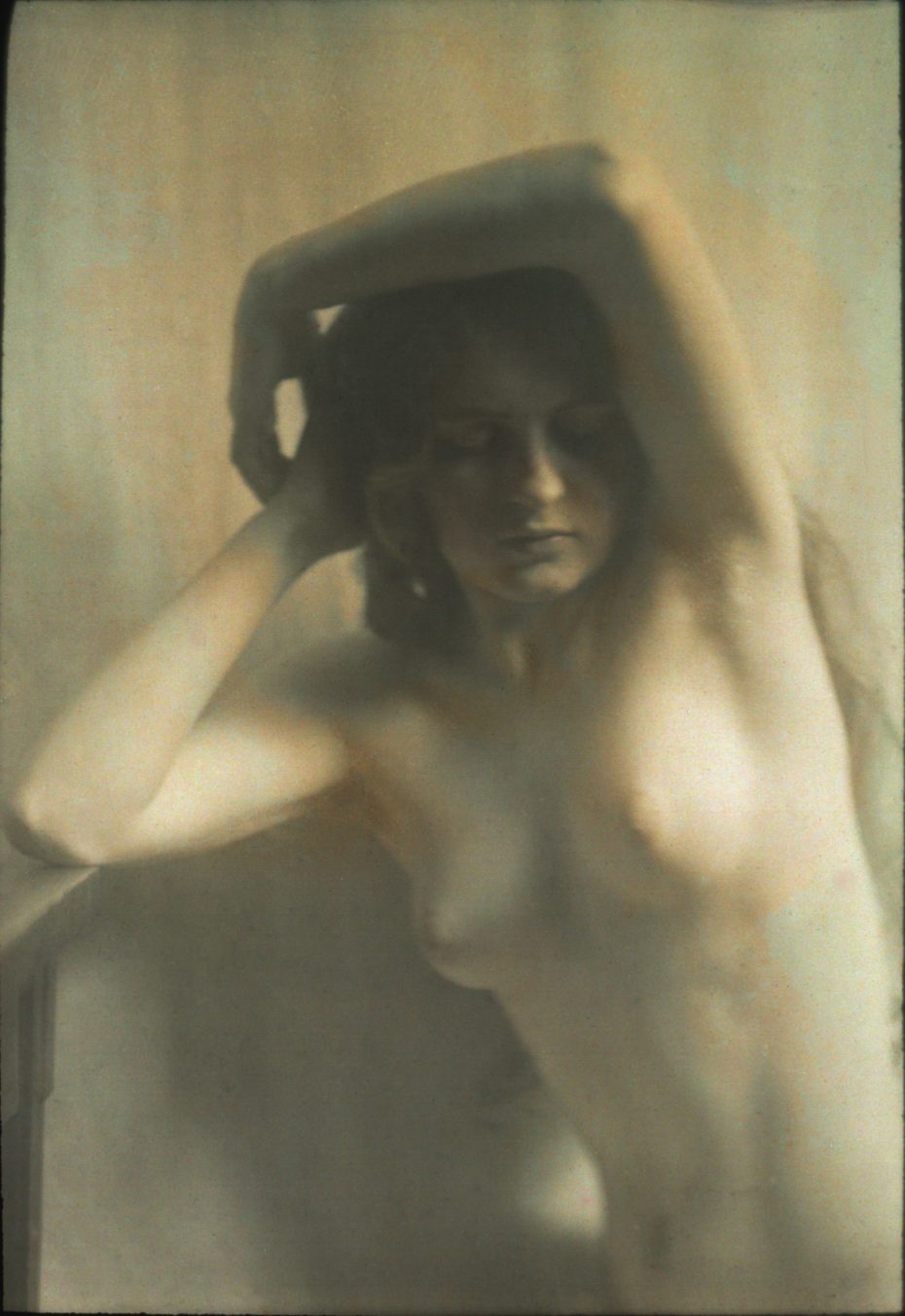

Contrary to what our history books would have us believe, the 20th century began in brilliant, bewitching colour. Long before colour film is thought to have been introduced to the mainstream population in the 1950s, Autochrome was the first successful photography media that gave the world vibrant, etherial photographs in the early 1900s, comparable to the dream-like paintings of Impressionism. It was the pioneering Lumière brothers who patented the process in 1903 when they introduced their mosaic colour filters – essentially glass screen plates coated on one side by a kaleidoscopic mixture concocted with an unlikely key ingredient – ready for this?

Potatoes! (But more on that later).

Despite being cherished for a brief moment in history, the unique and exotic method was soon forgotten when Kodak introduced Kodachrome colour film in the 1930s, but no technique invented since has ever matched the artistry of the Autochrome. After all these years, with all this technological advancement, there isn’t a photo editing tool or digital platform out there that has come close to recreating the beauty of this lost art– or making it accessible. Here at MessyNessyChic – we think it’s about time the Autochrome had a 21st century comeback.

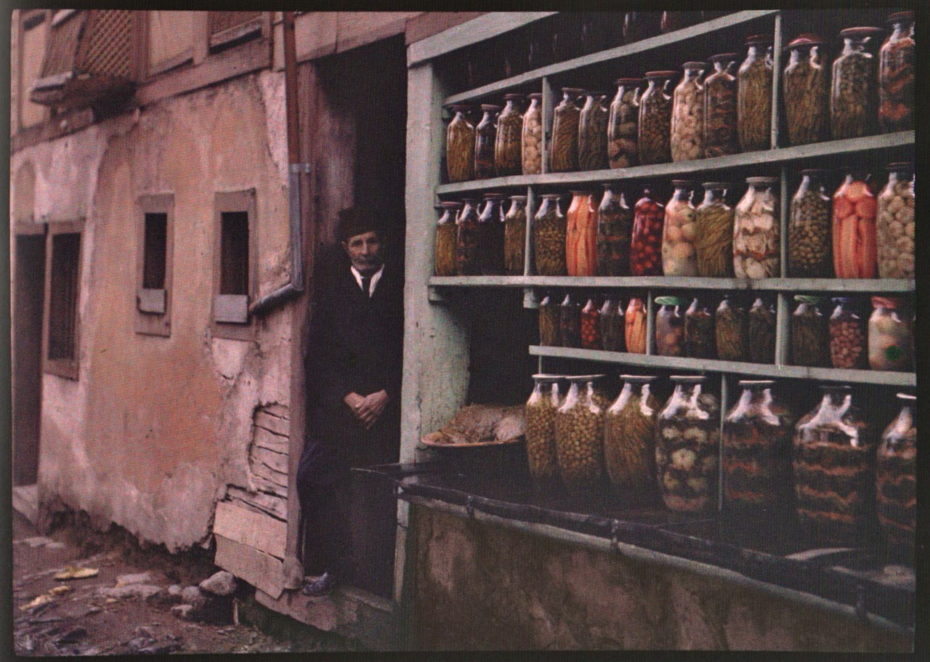

Once upon a time, Autochrome was considered the greatest thing since sliced bread. In 1914, up to 6,000 autochrome plates were being produced daily, and between 1907 and 1932, around 20 million plates were sold. During this period, particularly in France, where Autochrome Lumière had its most devoted following, French banker and philanthropist Albert Kahn commissioned one of the greatest, if not the most overlooked and undervalued projects in photographic history. Kahn’s “Archives of the Planet” sent photographers out to ‘autochrome the world’ – collecting a total of 72,000 Autochromes across 50 countries, over two decades – documenting people, daily life and scenery like no one had ever done before and likely never will again:

Albert Kahn Collection, Archive of the Planet

Using the Autochrome plates however, certainly had a few setbacks, which eventually led to its abandonment as a popular medium in the late 30s. Firstly, the film was slow, requiring much longer exposures, which meant you needed a tripod. So ironically, colour Autochrome was a huge step backwards from the more contemporary and convenient black and white hand-held “snapshooting” that was available.

And there was another issue with Autochromes – once you snapped the photo, it was hard to see anything on the resulting plates unless they were correctly illuminated. It’s more difficult than you might think to get a really true and accurate impression of an original Autochrome without seeing it in person, displayed in special conditions.

Stereoscope for viewing Autochrome

In fact, we should clarify that the “Autochrome” images you’ve been seeing on your screen right now are scans of photographs of Autochrome plates, which have been properly back-lit with dark surroundings, either using a stereoscope or diascope. In the early 20th century, this is how they were commonly viewed, through small hand-held box-type stereoscopes, allowing light to pass through the diffuser and the Autochrome.

A great number of Autochromes have been lost or damaged by folks trying to look at them using improper artificial light sources such as slide projectors and light boxes, which can effectively “fry” the plate, degrade the colour saturation and upset the rendition of a system which the Lumière Brothers carefully balanced and intended for natural daylight only. So the fact that it was difficult to publicly exhibit, also put off the serious photographic pioneers of the day that wanted to make a name for themselves.

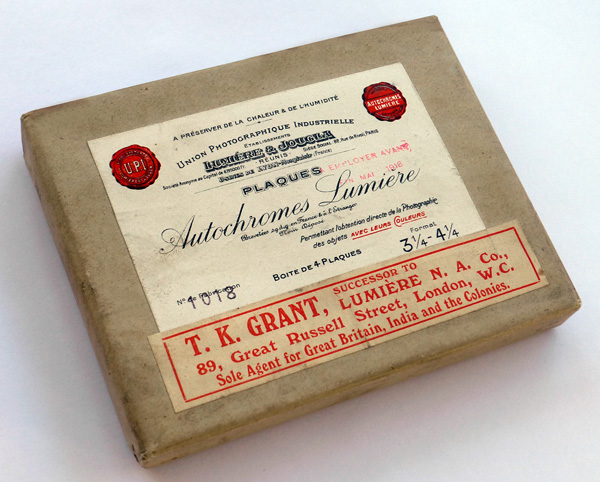

Okay, so despite the inconvenient setbacks and the costly process to manufacture the fragile plates in the first place, the medium was technically quite simple to use and became most popular with amateur photographers and well-to-do hobbyists of the era who had the means to buy Lumière plates for their cameras. The forgotten male and female pioneers of Autochrome captured some otherworldly photographs in their own back gardens, using their own families as subjects and capturing still-life scenes using objects found around the house.

The biggest collection of autochromes in the world is housed at the Albert Kahn Museum, at the banker’s former home in an unassuming corner of Boulogne Billancourt, just outside the city limits of Paris. But for decades, the museum was neglected and its precious archives ignored by the public. Only in recent years have efforts finally been set in motion to revive Kahn’s incredible legacy. While the gardens of the estate and limited collections are still open for visitation during the lengthy renovation period, the museum will not fully reopen with an experience that can do Kahn’s autochromes justice, until 2021.

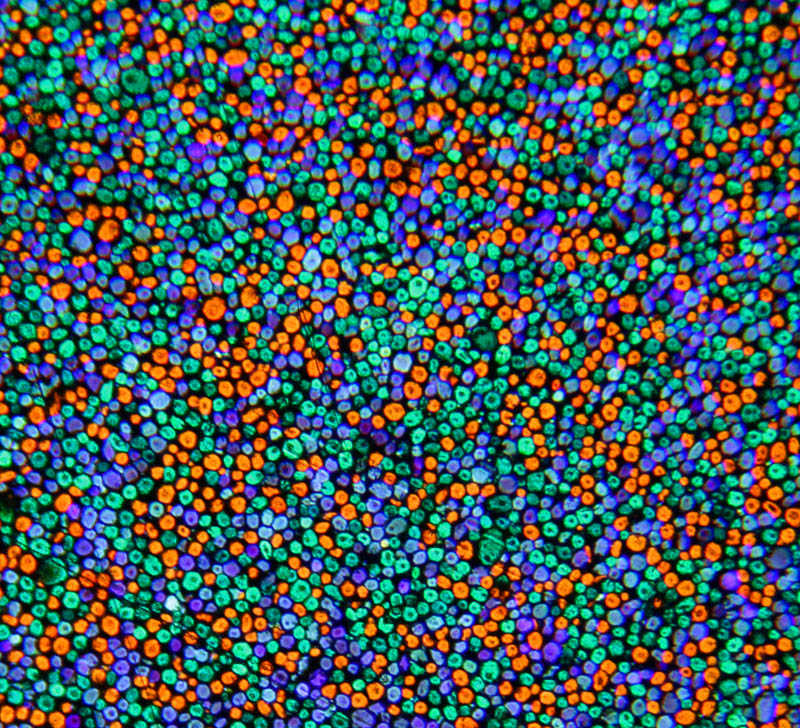

Now about those potatoes. Here’s a breakdown of the Lumière secret recipe that used the trusty spud to make their unique colour filters. Microscopic grains of potato starch, dyed red-orange, green, and blue-violet were mixed and blown onto varnished glass plates, resulting in a random mosaic of colours. And here’s what those coloured starch grains in an Autochrome plate look like, greatly enlarged, acting as tiny filters during exposure:

Next, a fine later of charcoal was applied to fill the interstices between the grains, and then the entire plate had to be pressed with a rolling pressure of 5000 kg per square centimetre without breaking the fragile glass plate. After pressing, a second layer of varnish is needed and to finish off, a top layer of panchromatic emulsion.

So you can see where the challenges might arise in trying to recreate the complexities of Autochrome using laborious editing techniques in computer software programs, let alone in social media apps like Instagram at the swipe of a finger. But is it impossible?

The good news is, we’re not entirely alone in our appreciation for the lost art and there are a handful “Neo-Autochromists” out there actually working with the original Lumière machinery and notes, such as Frédéric Mocellin.

And I found this one guy in the United States who is attempting to recreate the process digitally…

Mark Abeln is trying to discover the three primary colours used in Autochrome and coming up with a colour gamut that’s close enough to the original. He’s created a pixelated imitation of the Lumière colour grain pattern using Photoshop. You can see the result on his website here.

He uses custom ICC profiles, created in Photoshop, which he offers for download and can be used with standard image editing software to convert standard images with Mark’s version of the Autochrome primary colours.

“…these images lack prominent characteristics of the original Autochrome process, namely, the dark gamma of the images as well as the pointillistic grain pattern which derives from the coloured starch grains found on Autochrome plates,” writes Mark on his website. “Certainly my work with the Autochrome colour gamut is sufficient to produce interesting images with a limited range of colours reminiscent of Autochrome, but I think it would be interesting, and possibly valuable, to come up with a better digital imitation of the historical method.”

We’re rooting for him, but as for recreating Autochrome for the iPhone generation on a user-friendly platform like Instagram? The Lumière brothers remain unchallenged by the tech world.

So here’s to the person who can reinvent the Autochrome! And don’t forget my offer. I’d still like to buy that someone dinner, or better yet, take them for a champagne picnic here in Paris on Albert Kahn’s front lawn.

In the meantime, I’ll leave you with this quote John Wood on his book, The Art of the Autochrome.

Most autochromes do seem to have the authority of art – that power to rivet our gaze and demand of our eyes that they return again and again, and the power to reward those returns with pleasure and insight. It would be interesting to know what it is about the autochrome that so compels, to know why that soft glow of suggestion, of elegant ladies in lace, of nuance and the Monet-haze of dream is so emotionally gripping, so psychologically arresting.

All Autochromes (except for Albert Kahn’s “Archive of the Planet” collection) were found from a collection of Belgian Autochromats curated by Florent Van Hoof.