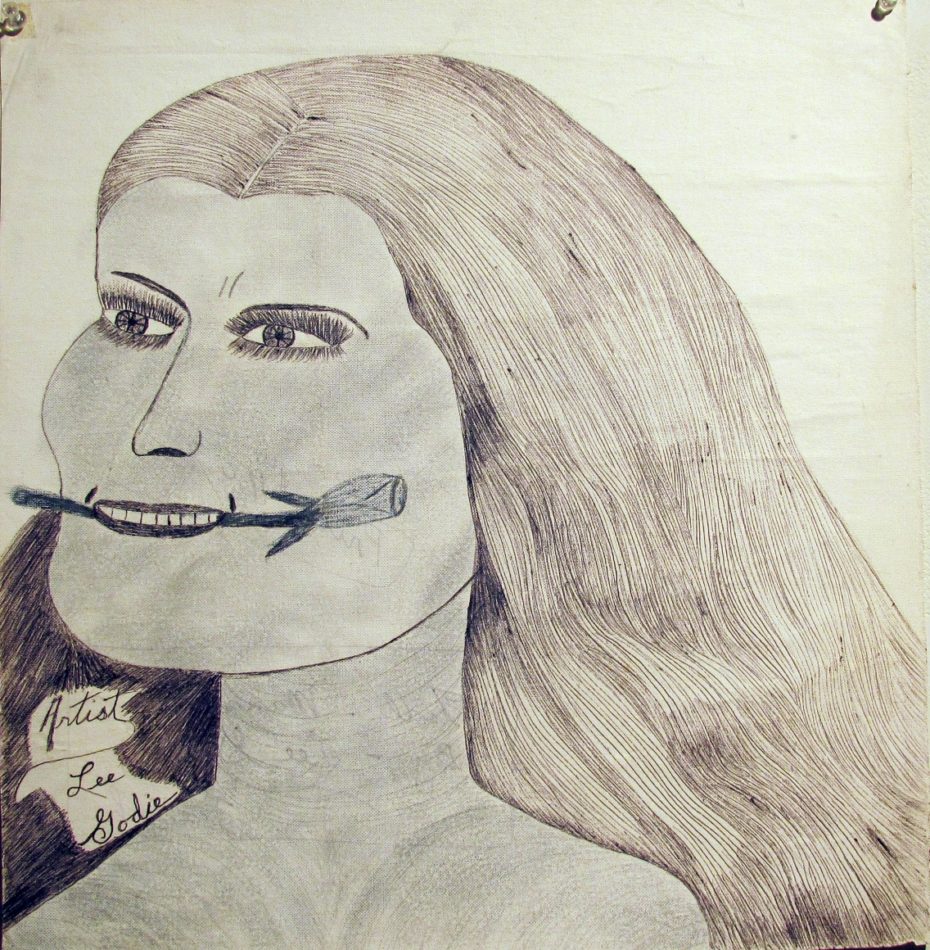

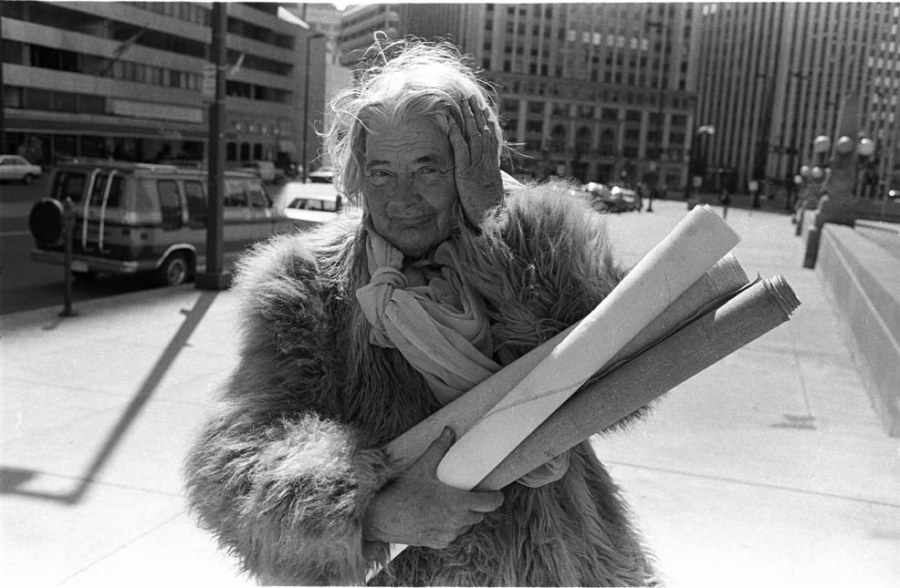

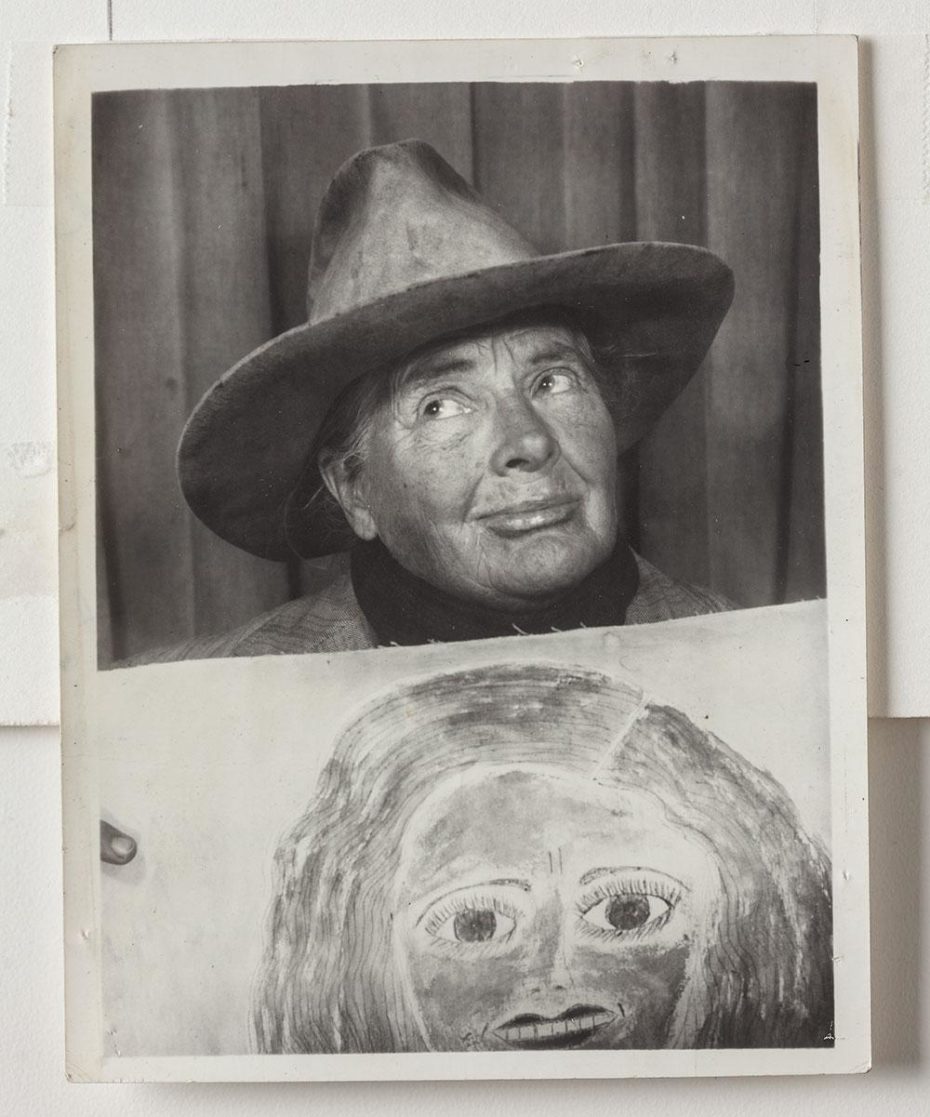

“I’m much better than Cezanne,” she would say if you had the opportunity to cross paths with Lee Godie selling her canvases on the steps of the Chicago Art Institute. She was a homeless self-taught artist who floated about town for many years; her arms full with artworks, wearing a patched-up fur coat, hair wild but beautiful, like Godie herself.

She had a unique way of selling her work, to say the least. Lee would tease passers-by, slowly unrolling her canvases to give them a peek, but if there was something she didn’t like about a potential customer, she would quickly roll them back up and scurry away without another word. If Lee Godie decided there was something she didn’t like about you, there was no amount of money in the world that would convince her to sell you a artwork. She became one of the windy city’s most infamous eccentrics and whilst some would seek her out on the streets of downtown, most kept their distance from the unpredictable but prolific outsider artist who is now considered Chicago’s most collected artist.

It was a distressing turn of events that completely transformed this woman’s ordinary, middle-class life. Godie was married twice and had four children, but when she tragically lost two of them, she decided to leave everything behind and re-invent herself as an artist. From 1968 until 1991, she was homeless out of choice, and would make her creations wherever she could.

When the Wall Street Journal published an article on an artist living on the fringes of society, Godie was reunited with her estranged daughter, who had not seen her mother since she was 3 years old. Her skin showed a rich history of exposure to the sun, and her clothes were just as flamboyant as her personality. Even in the middle of July she’d be wearing a fur coat, which would have all kinds of treasures hidden inside its pockets.

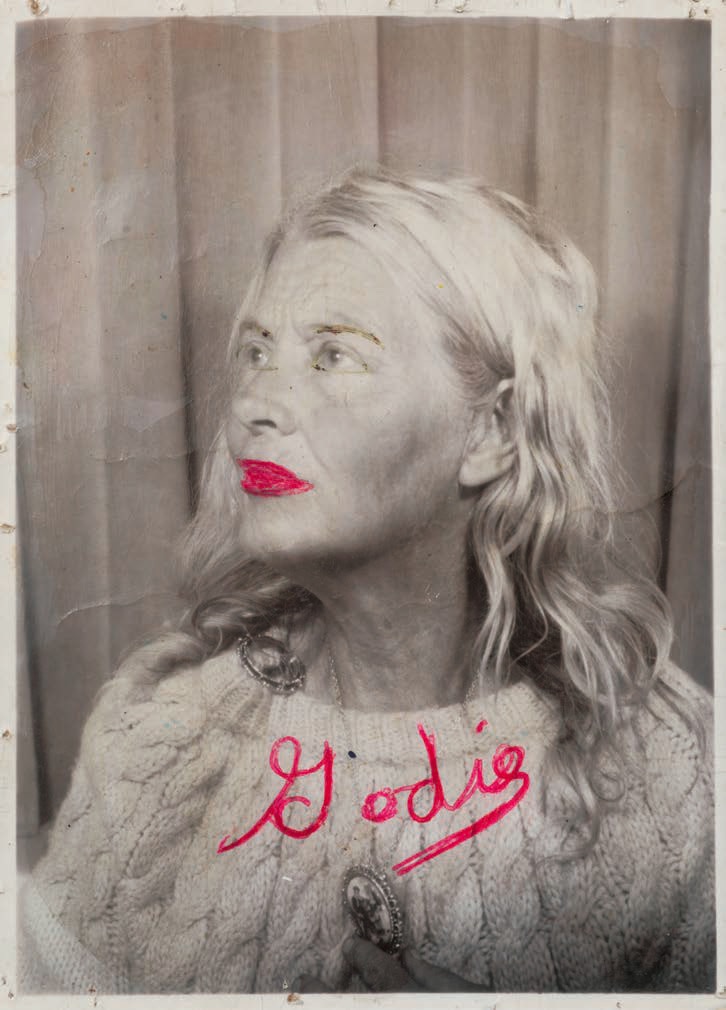

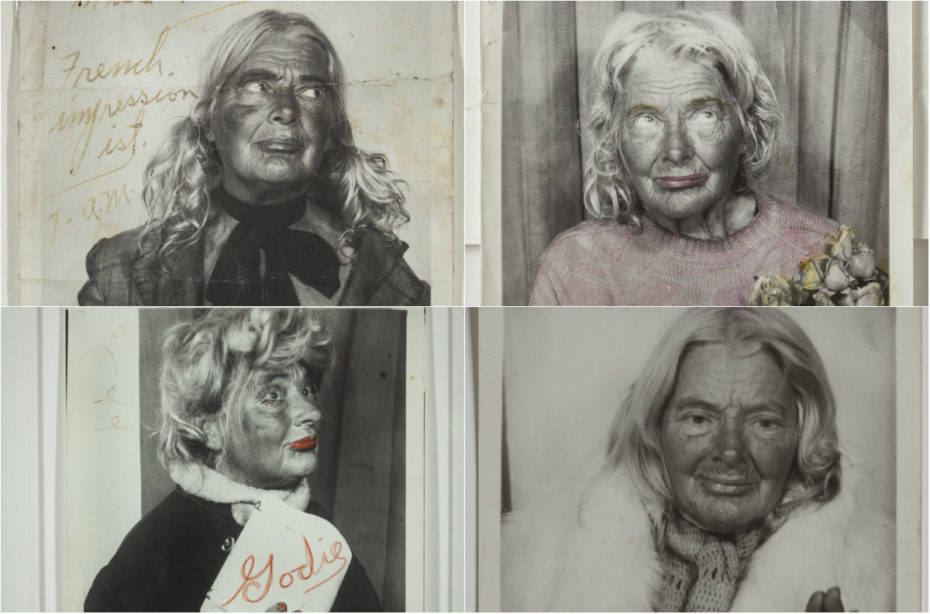

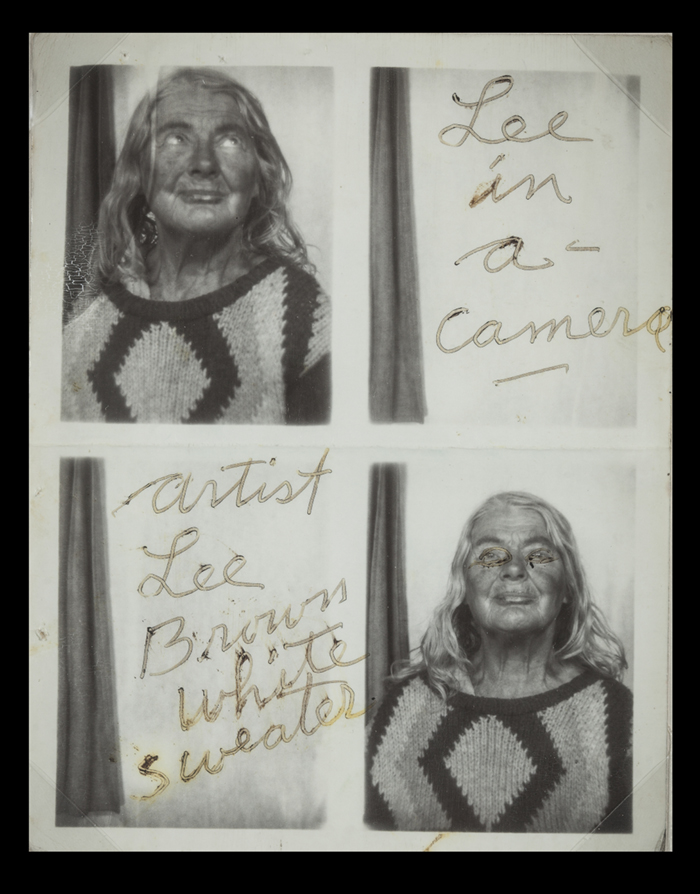

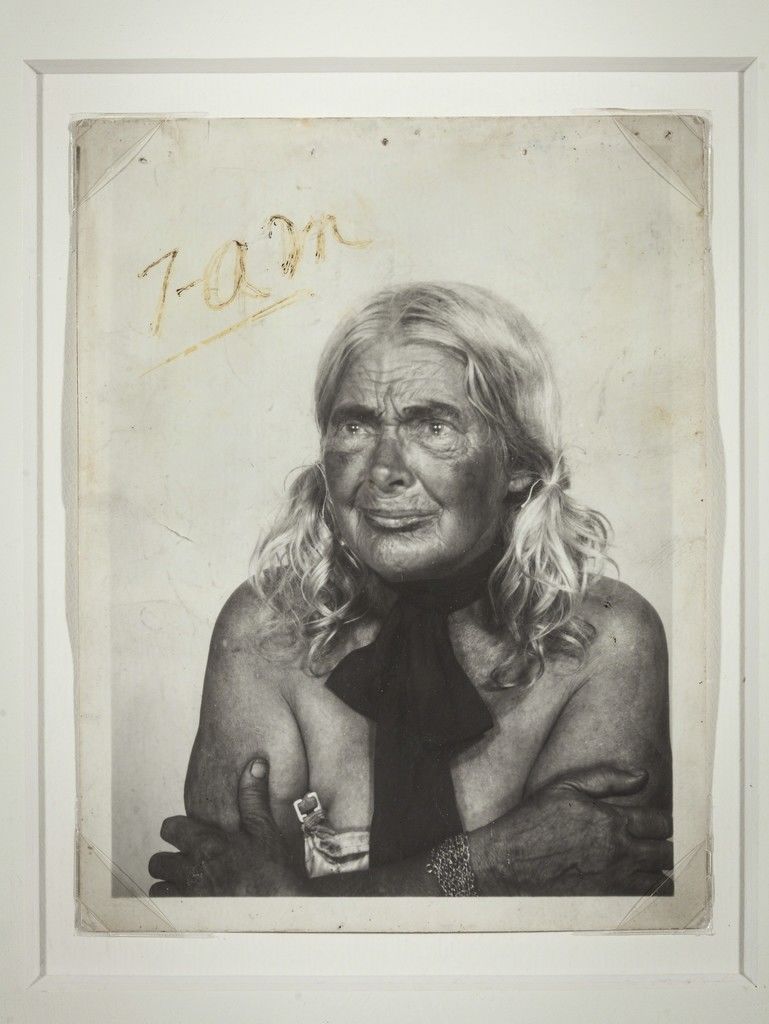

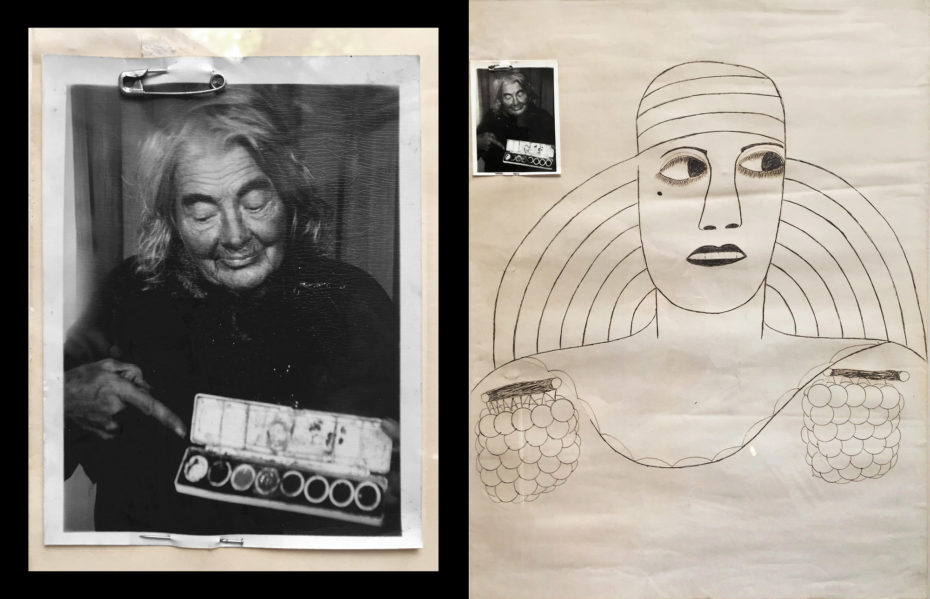

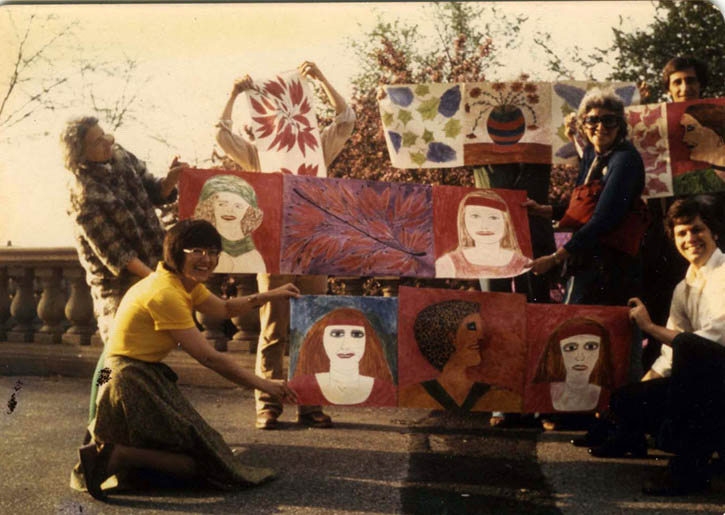

Like the recently discovered nanny-photographer, Vivian Maier, Chicago was at once her studio and her muse. Godie would make artworks with any materials she could get her hands on; broken glass from a car window, discarded window blinds. As a painter, she developed a relationship with a local art dealer, Carl Hammer, someone who she trusted enough to later carry and sell her artwork. In the 1970s, she began experimenting with mixed media and some of her most impressive and significant work was created in the middle of a busy Greyhound bus station in the city, where she took hundreds of self-portraits in a photo booth that produced 5 x 4 gelatin silver black-and-white prints. This was her stage. A place where Godie could perform in front of the camera, and capture all kinds of different personas. Some biographical accounts suggest that Lee had tried to become a singer in her youth, but was hindered by a controlling husband.

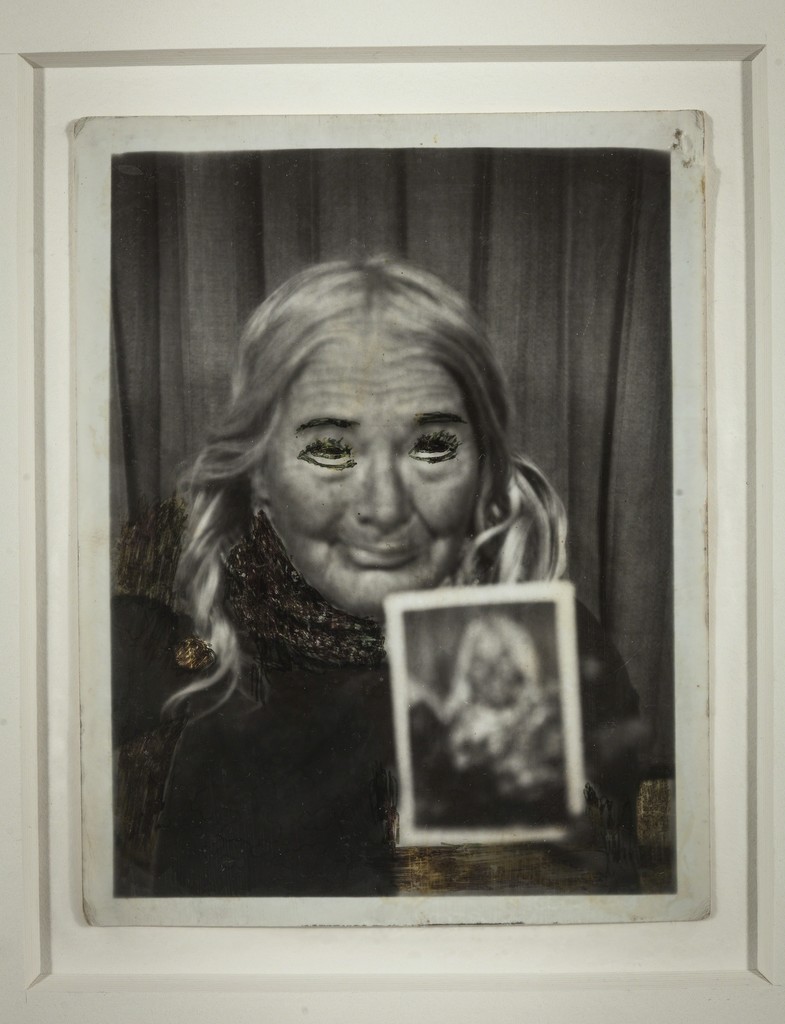

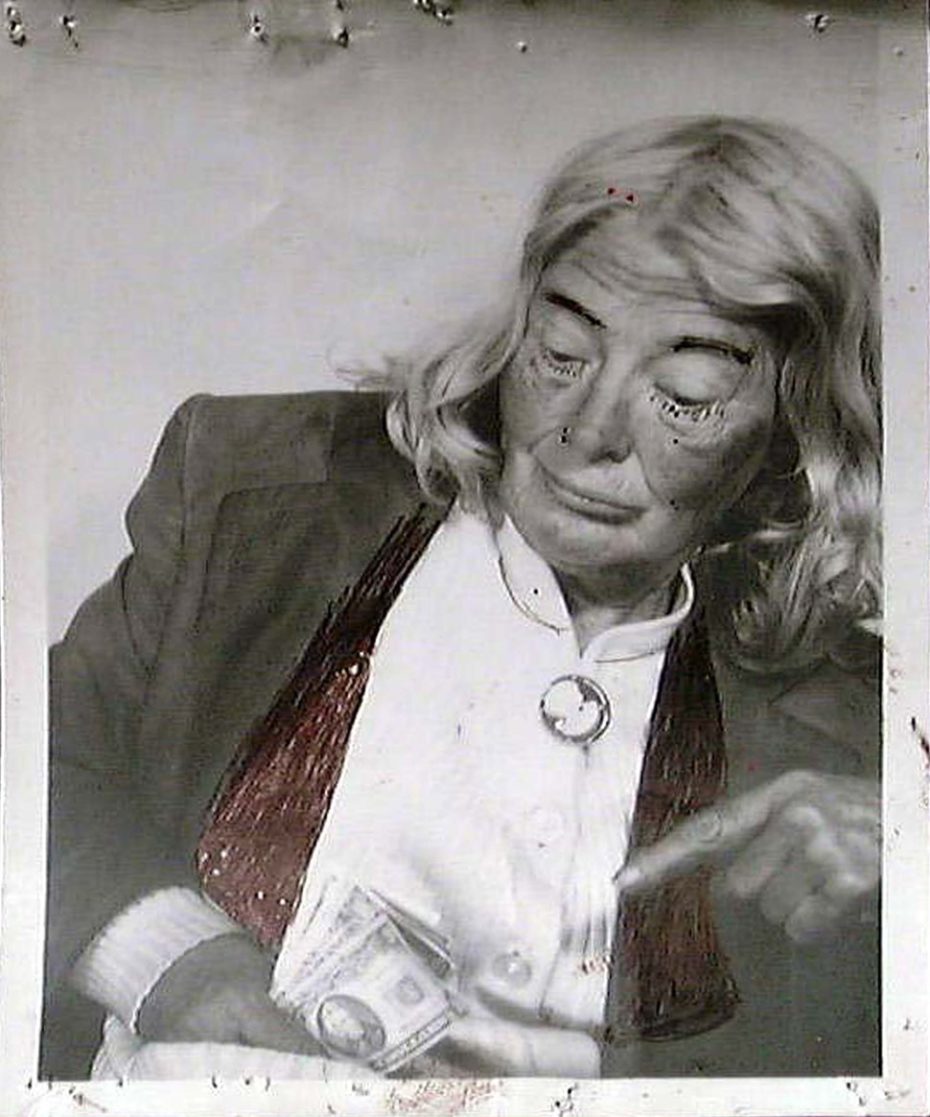

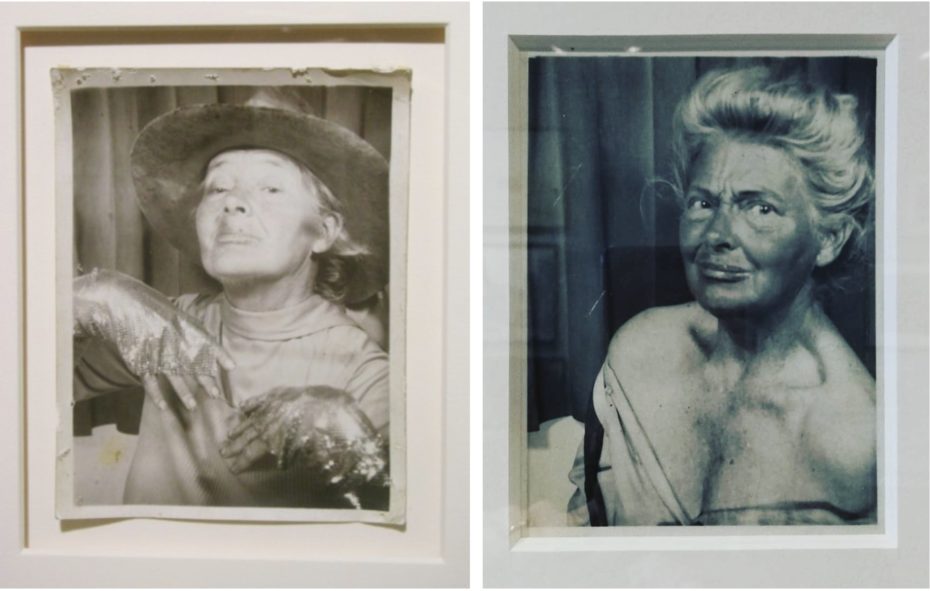

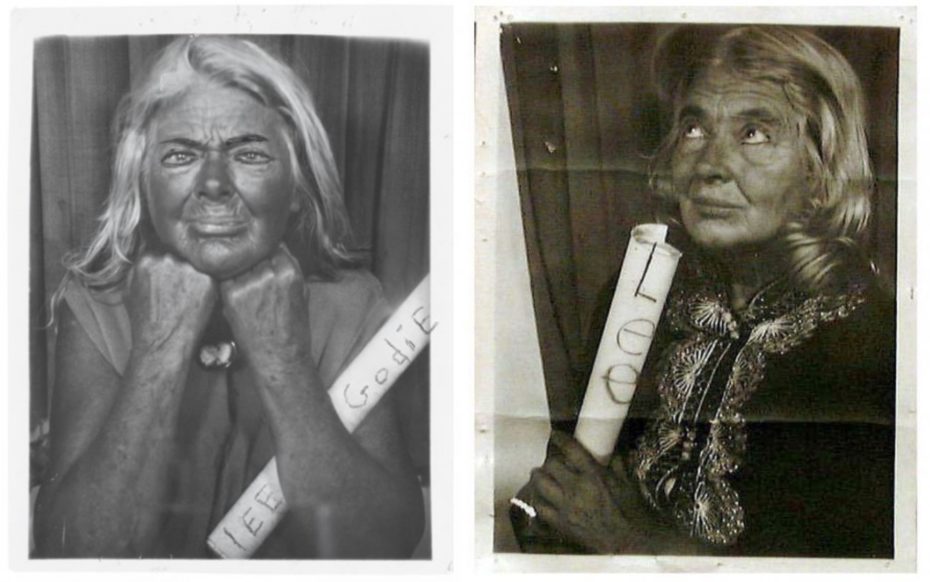

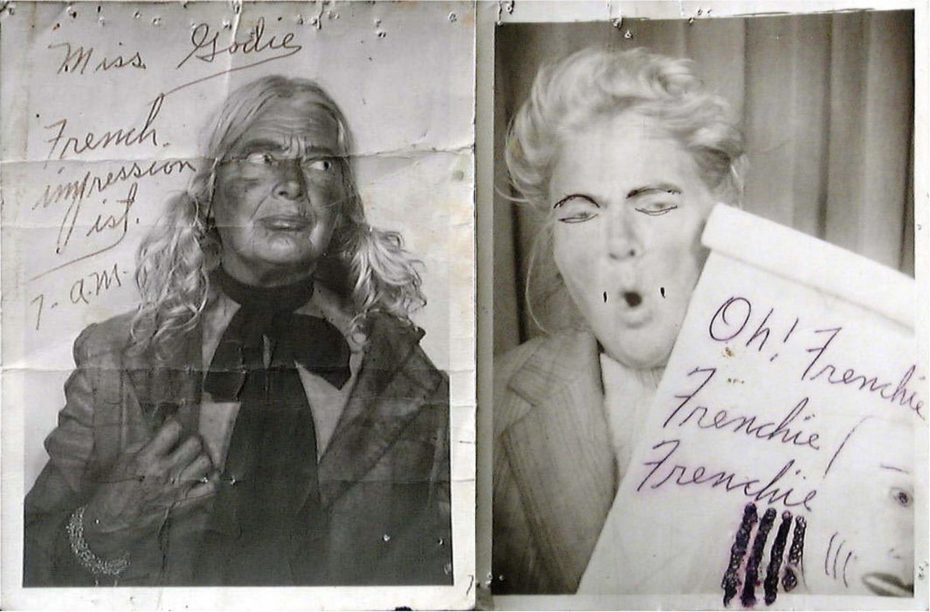

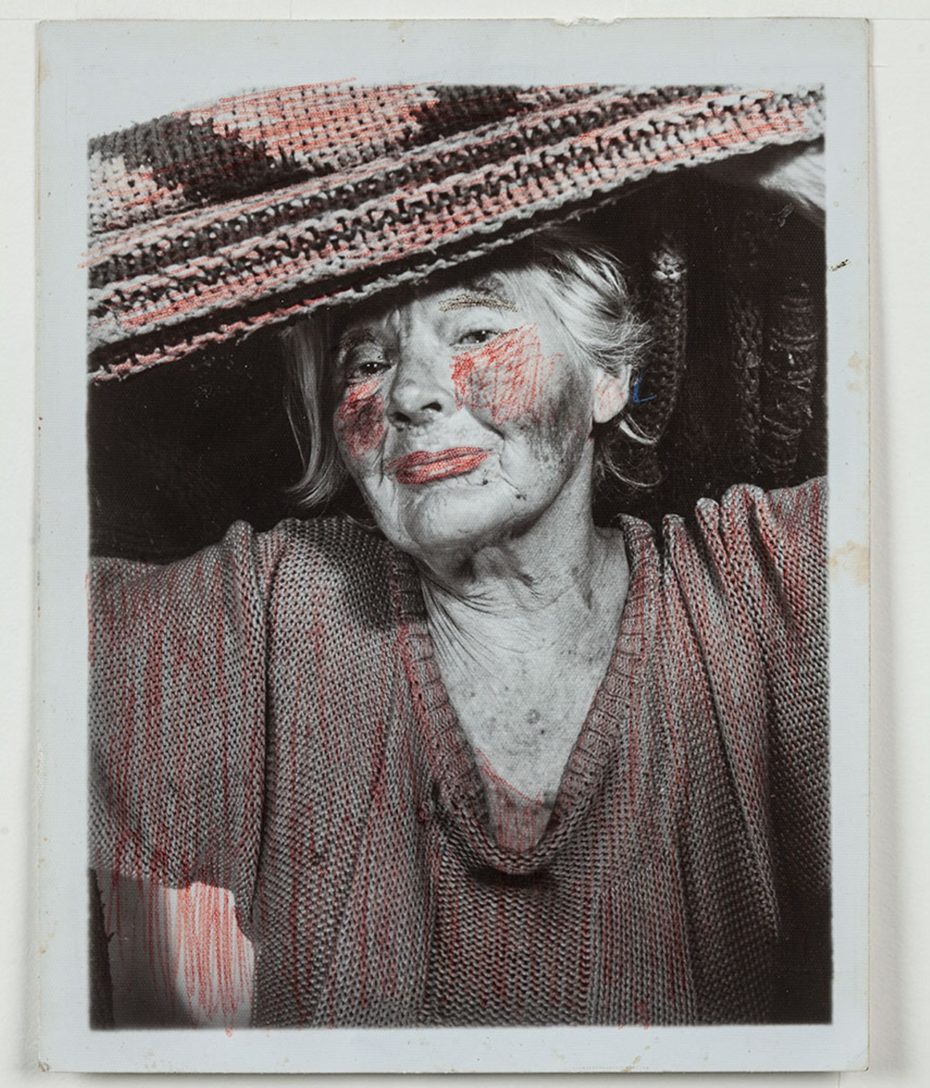

Godie’s photographs show her pulling ostentatious facial expressions and poses, using props and accessories to portray different characters. In one, Lee Godie wears a suit and tie while holding cash in her hand looking very serious, as if to poke fun at the workforce in the financial district. In another, she exposes her shoulders like a glamorous Hollywood star, sporting an elegant Gibson girl hairstyle.

In between takes, she would sometimes quickly remove herself from the frame and then jump back in the booth. Once printed, she would fill the blank photographs with writing, decorate her face by drawing on juicy red lips, bright coral cheeks and darker eyebrows.

The photobooth was Godie’s private space where she could let go, revealing a more playful or vulnerable side. The bus stop photos, allow us to stop and really look at Lee, who was often skittish with strangers and highly secretive about her personal life. She was known to pretend that she didn’t speak English when approached by journalists. The nomadic artist was not always easy to find and encounters would be fleeting, but here, in these rare photographs, her delicate features and flaws are mesmerising. This is the personality that very few saw.

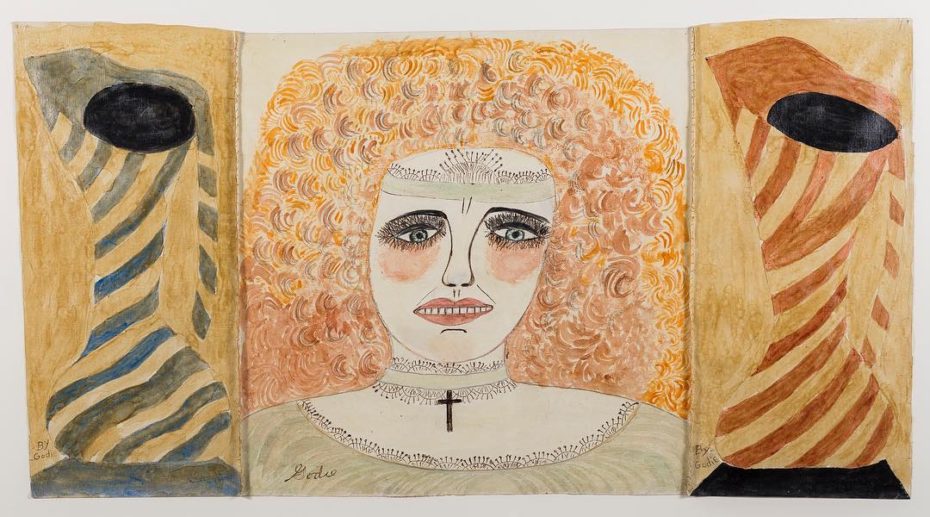

Usually these portraits would stand on their own, but sometimes they’d be sewn onto her larger paintings. Most, of the bus stop photographs are in private collections and rarely shown in public exhibitions. Godie’s wider oeuvre includes brightly coloured paintings of friends, celebrities and anonymous passers-by.

She was a true flâneur in the Baudlerian sense that she had the ability to wander detached from society with no other purpose than to be an acute observer of society. She was a francophile in spirit and famously went around calling herself a French Impressionist.

Lee Godie often painted birds too, and she said that it was a little red bird that spoke to her and told her to paint. She once threw a red party in the park under a tree with red flowers at dawn and served a strange array of red foods on a red table cloth alongside her paintings, which were also, all red. She also sang and danced for her guests.

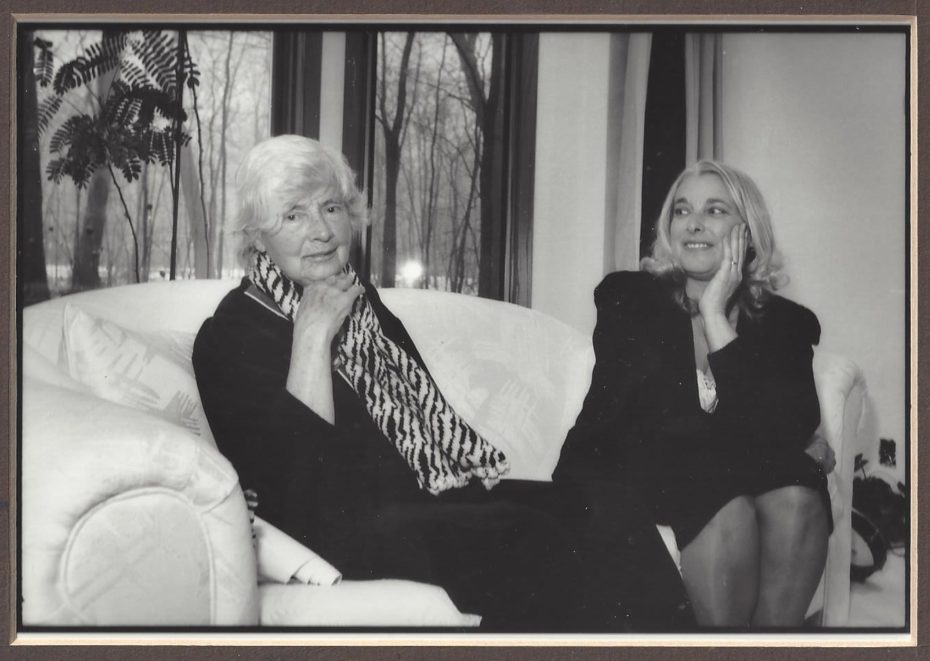

Being homeless meant that Godie’s life wasn’t easy. From day to day, she had to battle the elements and the dangers of living on the street. After three decades of homelessness, Bonnie Blank was granted legal guardianship of her estranged mother in 1991 when she discovered what had become of her through the Wall Street Journal.

Lee was suffering from dementia and moved to a nursing home in Illinois where she gave Bonnie art lessons and reconnected with her family before she passed away in 1995.

Art historian Debra Brehmer wrote that the line between reality and fantasy was blurred in Godie’s photographs. She said that the “images showed who she was and who she hoped to be all at once”. Her unconventional personality and lifestyle were completely intertwined with her art: they were one.

Today, her work is exhibited all around the world, and most importantly, at the Art Institute of Chicago, next to the works of the other great French Impressionists, like Manet, Monet and Renoir.