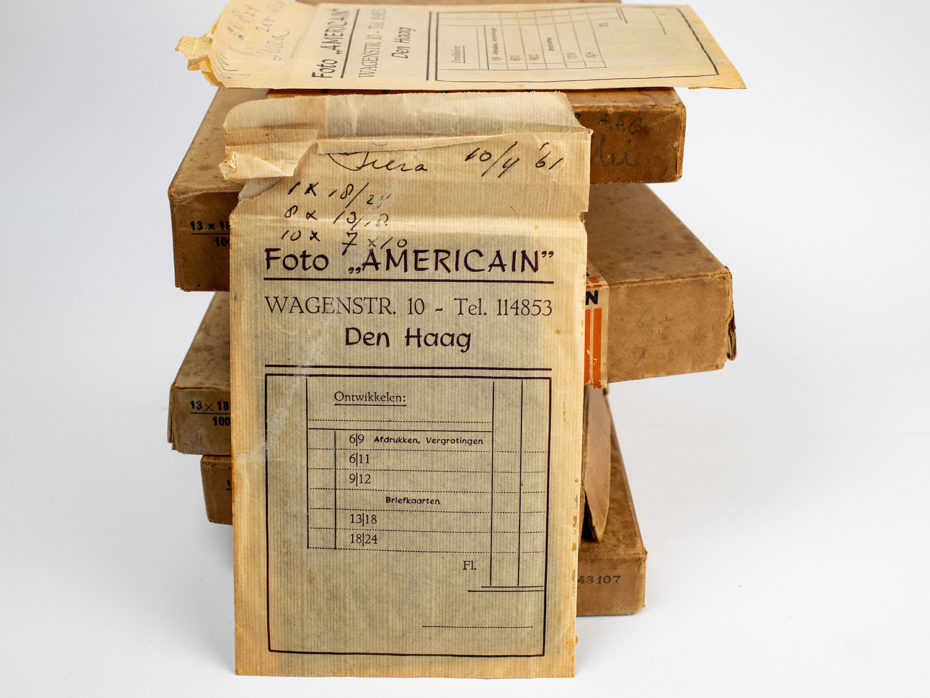

Ernst Lalleman doesn’t make friends like the rest of us. “I was mesmerized by the quality, as if I could hear the voices of these people talking to me from the past,” he told us about the collection of 235 portrait negatives he found so many years ago, and have been his silent companions ever since. “It was in 1987, [and] we squatted in an abandoned building in The Hague, in the Netherlands. The corridors and most rooms were full of dog [waste]; we were attacked by flees. The building had been used by junkies.” Then, in an old filing cabinet, Ernst hit the jackpot: six vintage boxes containing perfectly crisp, anonymous colour negatives that captured his imagination.

In that moment, he knew he had to save them “from total destruction.” But the project that ensued from their salvation would become one of the most meaningful in his lifetime. Over the years, Ernst has come to know every portrait’s crease, frown, or smile, and he told us why it’s so important for him to not only share those faces, but return them to their rightful owners.

One of the most striking things about the images was their condition, and coherency. They all come from the same collection, dated from May 1959-August 1960, from a then-prominent studio called Foto Americain in The Hague. Funnily enough, Ernst’s grandfather also got his portrait taken at the studio in 1939. Call it fate if you’re a romantic, or serendipity if you’re a skeptic – either way, it’s a pretty magical parallel.

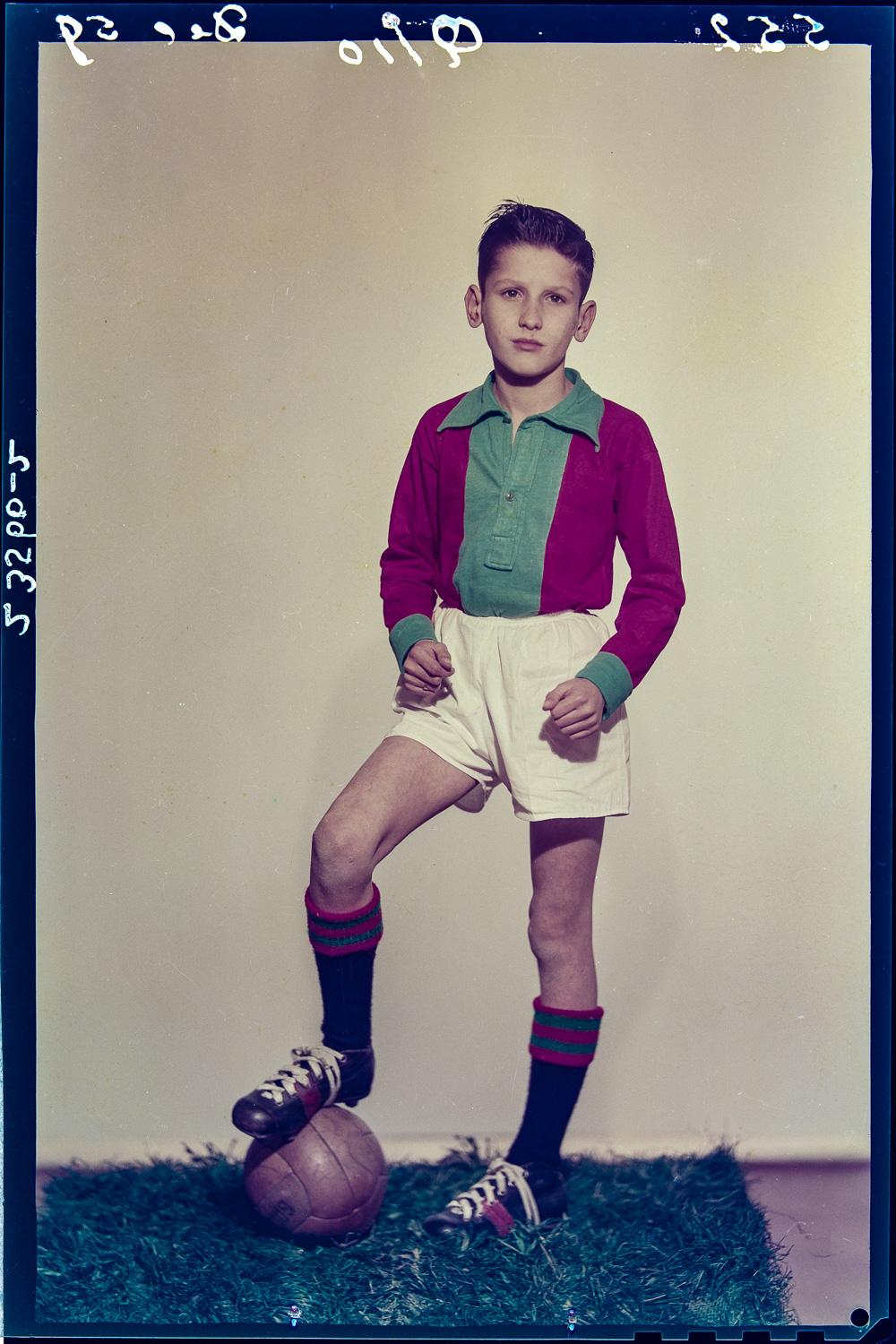

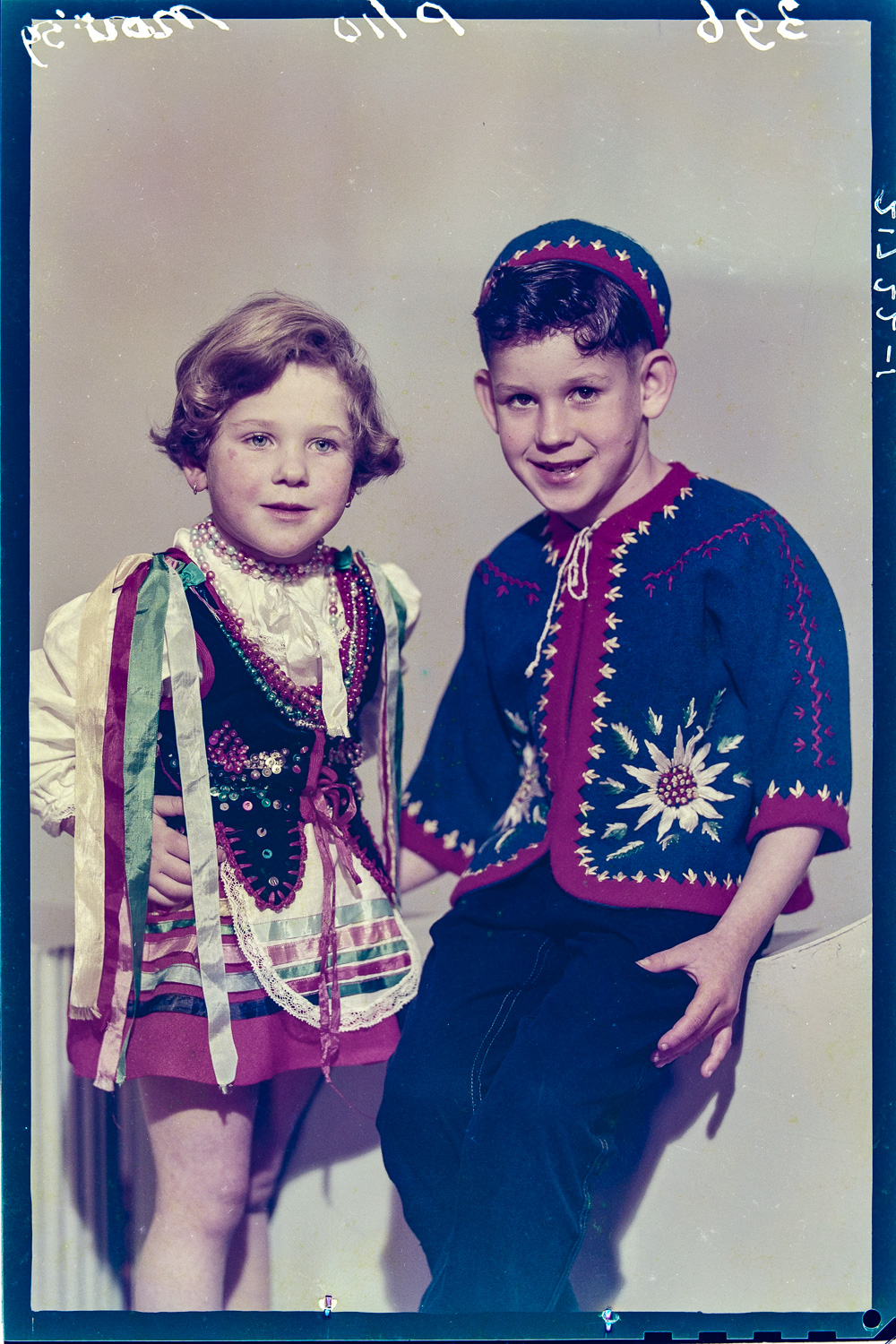

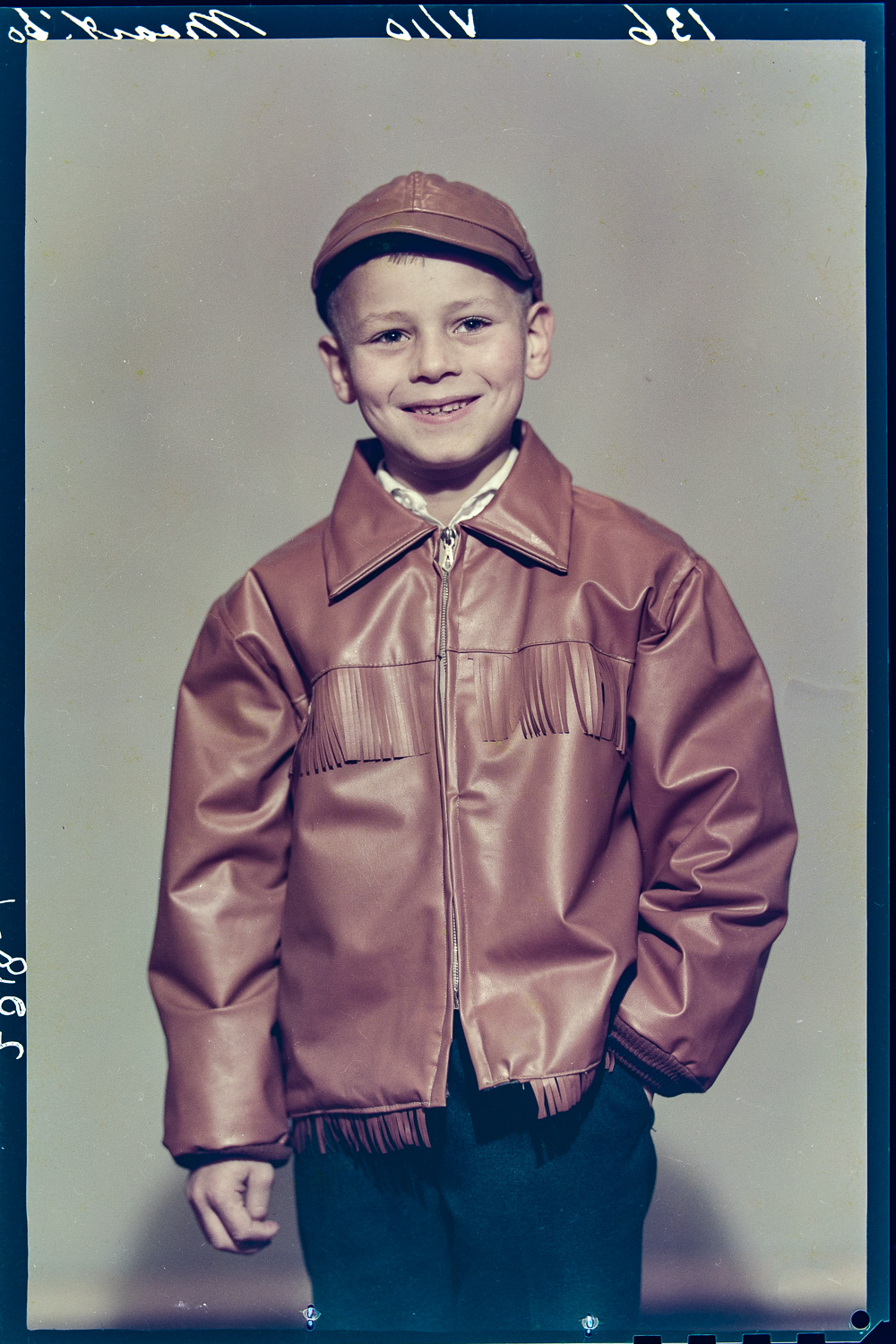

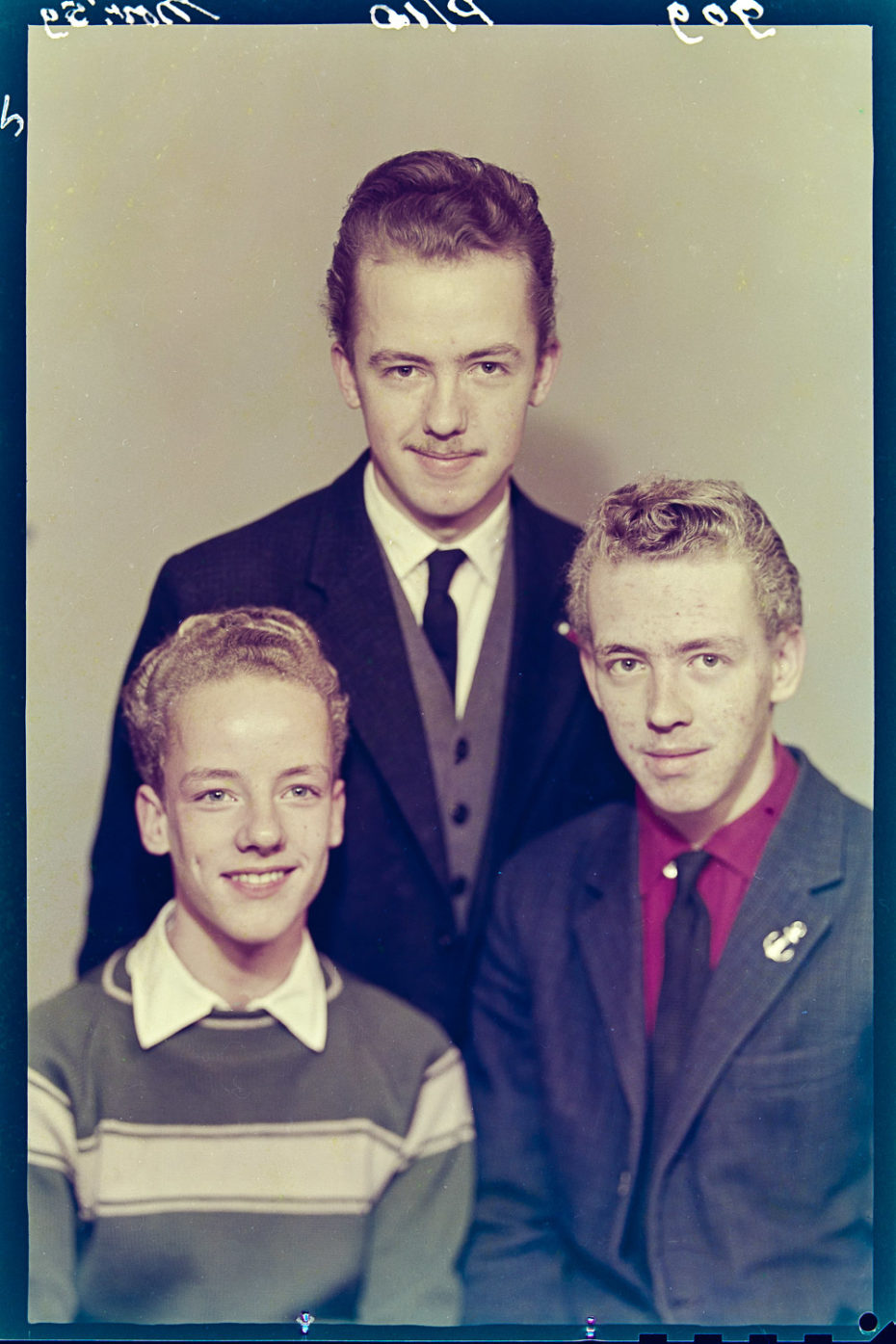

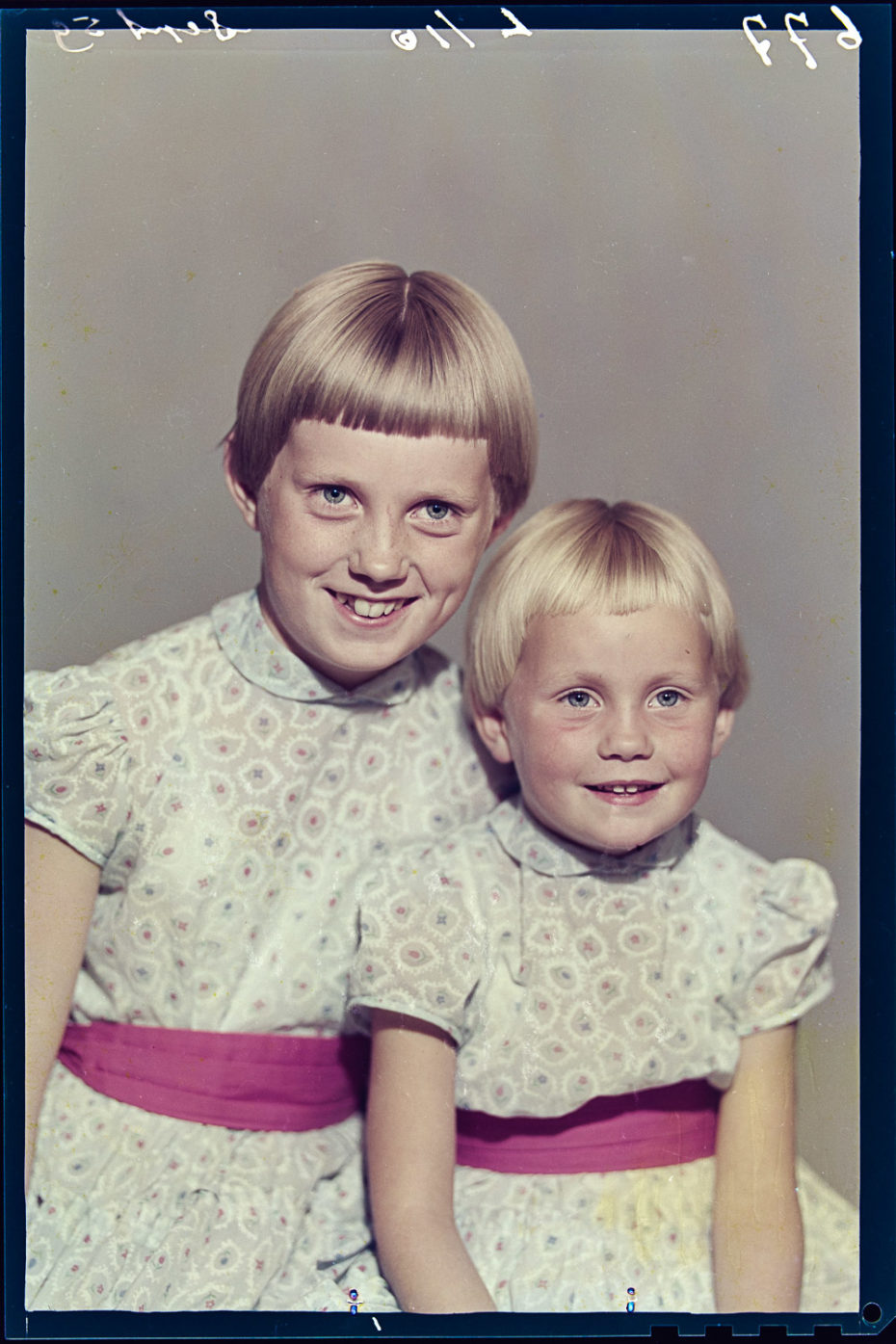

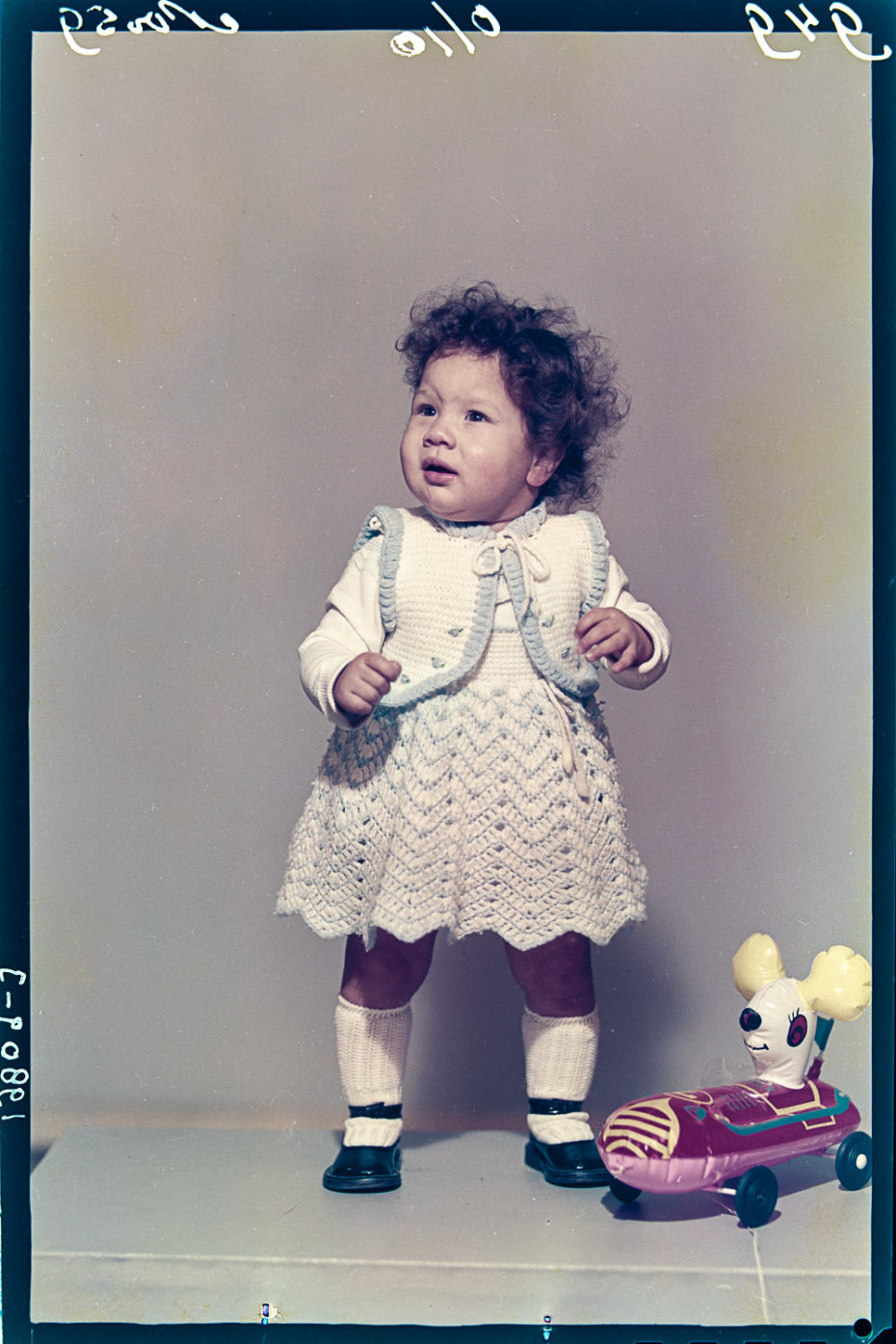

It’s no wonder Ernst has been enchanted with the photos after so many years years; there’s something about them that feels both familiar, and otherworldly. Perhaps it’s the ethereal pastels that colour each one, or the fact that each plastic flower petal, and blade of AstroTurf looks crisp enough to pluck from the picture — or simply because, for the most part, they look so warm. Almost as if they’ve been expecting you (and not just because it’s a photography studio).

“Being a young photographer I printed some of them as a black and white contact print in my darkroom,” says Ernst, “Of course we didn’t have internet, social media, etc. So I didn’t really know what to do but save them securely as a treasure.” For years, the photos slept in silence, tucked away in their cellophane sleeves.

Then, the digital revolution came. “The objective [was] to return these allegedly lost photos to the portrayed people,” he says, “When somebody has recognised him or herself or a family member, I send them the hi-res, digital image.” The internet and social networks have, of course, been key in connecting folks with their long-lost pictures. At present, he’s returned 35).

“I hope that I help people realise that photography is not about having a zillion images in their cell-phones,” he says, “that [we swipe] through without actually “looking” at them. I’ve received hundreds of enthusiastic emails of people telling me how they’ve enjoyed going one by one through the collection, trying to imagine the lives of the portrayed people.” He calls that experience “slow photography,” and chalks its popularity down to a resurgence in the demand for “genuine images that show the authenticity of stories.” As a photographer himself, he says that even his own clients “want to envisage a real and tangible world” through their photos.

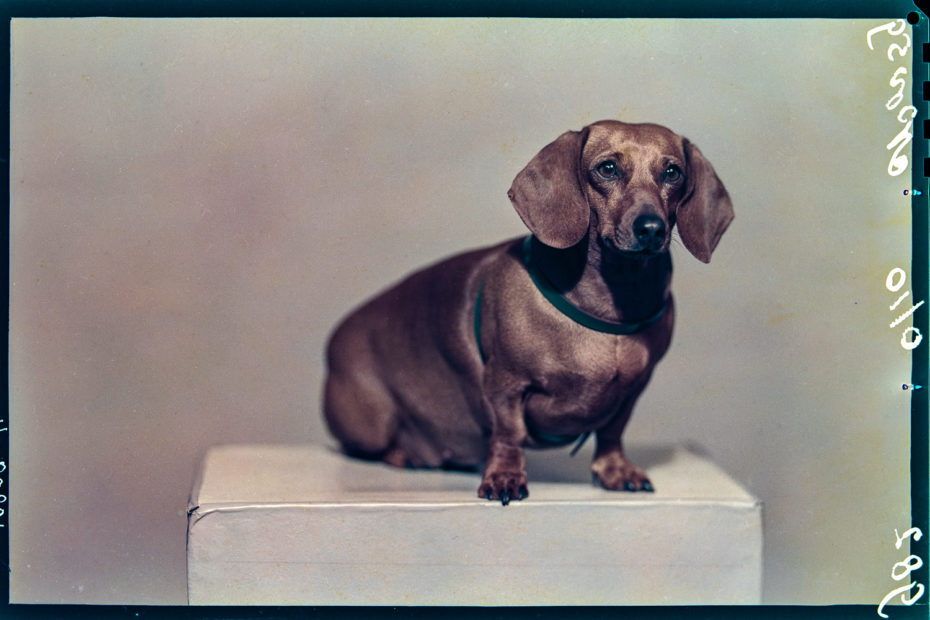

Ernst is arguably more than a photographer and archivist. He’s the keeper of imagined lives, the narrator of stories one can only project onto a smiling girl in overalls, or a dachshund patient enough to sit for a view camera photograph – some of his favourite snapshots in the lot, which he chalked down to the following five. Starting with “The Dachshund”…

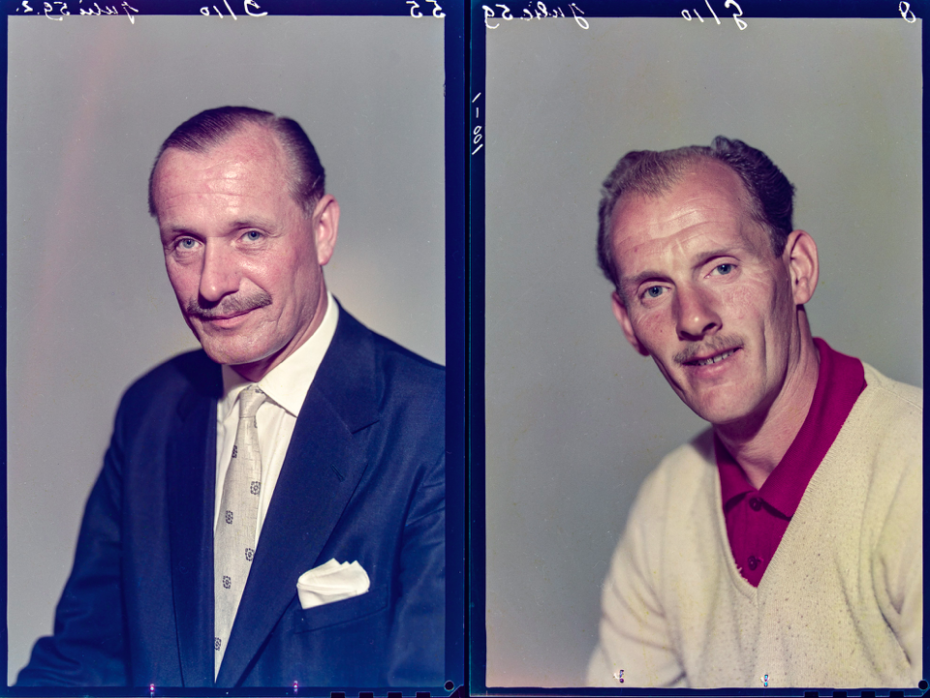

“Everyone who has ever tried to photograph their pet knows how difficult it is,” he says about the feat of the dog portrait, “these photos are taken with a view camera. First you open the lens, you manually focus, you close the lens, then you shove the cassette with the unexposed negative in the camera, remove the slide so that the negative can be exposed when the lens opens, and then you release the shutter.” So, yeah. This was one hell of a well-trained dog. “[Look at] its eternal character,” says Ernst, “its personality!” Then there are “The Two Men,” a pair he’s made of photos 61 and 62.

Images 62 (left) and 61.

Images 62 (left) and 61.

“They’re more or less the same age, their position is equal, and they wear mutatis mutandis the same clothes,” he says, “The man in the suit is a distinguished gentleman. He shows a certain modesty, and when asked a question he will humbly give the expected answer because he is well-behaved and he believes he is rather posh (a typical trait of certain people from The Hague. I know this so well because the family of my mother’s side is from The Hague and were like this). Now the other man is a typical bloke who lives in a different neighborhood, his attitude is blunt and rather unfriendly. When he opens his mouth, [it’s in] a rant of swear words in the common accent of The Hague (Also very typical! You could compare it to Cockney).

Next up, “The Family,” image no. 092. “Four individuals who are clearly united,” says Ernst, “The young man on the left with his beautiful blue eyes and intelligent glance, the distinguished mother who has the looks of a queen from a fairytale country, the father who has just uttered a private joke and seems he happiest man in the world. I am dying to get to know this family!”

Image 92

Image 92

Last but not least, there’s the crown jewel of the collection: Marian, no. 215. Her’s was the only negative with a name. “If we look at her body language, it is clear that she is completely relaxed,” he says, “this photo seems to be a snapshot, whereas all the other portraits are posed. Holland was in 1960, [and] on its way to its most booming economy ever. We had just overcome the destruction of the country by WWII, and reconstruction was almost accomplished. Her open smile, her healthy complexion and her “I can face the world” posture [encapsulates] that era perfectly. And she is also just adorable in her blue dungarees, of course.”

At the moment, Ernst is developing a project in which he’ll bring the stories of folks who’ve recognised themselves, or a loved one, to life with the addition of contemporary photography. “A lady recognised herself and her little brother in two photos,” he says. Their father was a sailor, and regular pictures of the kids made him feel closer to home. Another woman, he says, who was slightly older and with dementia, recognised her 20-yr-old self instantly. “How pretty I looked then!” she declared.

If shuffling through so many faces has taught Ernst anything, it’s to find what you treasure, “independent of the value in money,” and hold it close. Spend time with it. Your treasure, be it “an object, a photo, or a cufflink,” will never cease to reintroduce itself to you over the years if you let it.

All images courtesy of Ernst Lalleman. Learn more about his project “Who are We” and his work on his site. If you recognise someone – or yourself, you can contact him here.