Sometimes, you hear what you wanna hear. Especially in Hollywood, where a coconut steps in for the hooves of a horse, and squishing canned dog food is meant to mimic the sounds of aliens and monsters. It’s all a part of “Foley” making, a term coined after Jack Foley, who pioneered post-production sound effects for radio, TV and movies during the rise of “the talkies” in the 1920s. Those that succeeded him in the profession are today known as “Foley artists,” and they’re ironically Hollywood’s biggest silent players and oft unrecognised talent, because the mark of a great Foley artist is when the sound effects are so well integrated into the movie, you never even notice…

“On Sundays after Mass, our kitchen became a sound stage,” remembers Foley’s granddaughter in an interview with the Irish America in 2012 (Foley was himself a 2nd generation Irish-American), “My grandfather and the kids would be playing around with all sorts of things from the house trying out different effects on the table.”

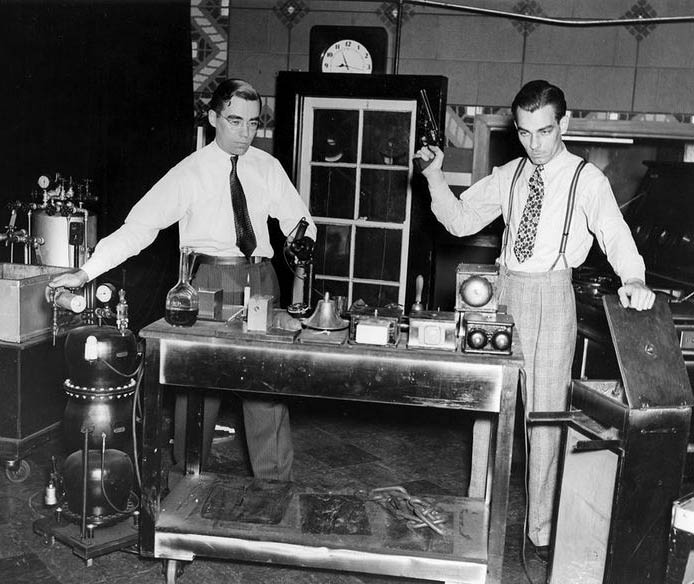

As silent films were left behind and film audiences were demanding more “talkies” with sound, Hollywood had to navigate a new, noisy world, and Jack Donovan Foley was at the forefront of it. The New Yorker had moved to California to work in the movie business, and did so for almost half a century, along with a string of other eccentric jobs (cartoonist, stunt man, painter, semi-pro baseball player and more). But it was sound effects that would be his true calling, and he turned it into an art form. A foley may seem like an afterthought of the content we consume, but in reality, it intensifies the moments that tug on our heartstrings the most in a film, from the brush of a hand to the cock of a pistol. Without them, we’d live in a world where movies are seen – but not quite experienced. So let’s break down a few secrets of the trade…

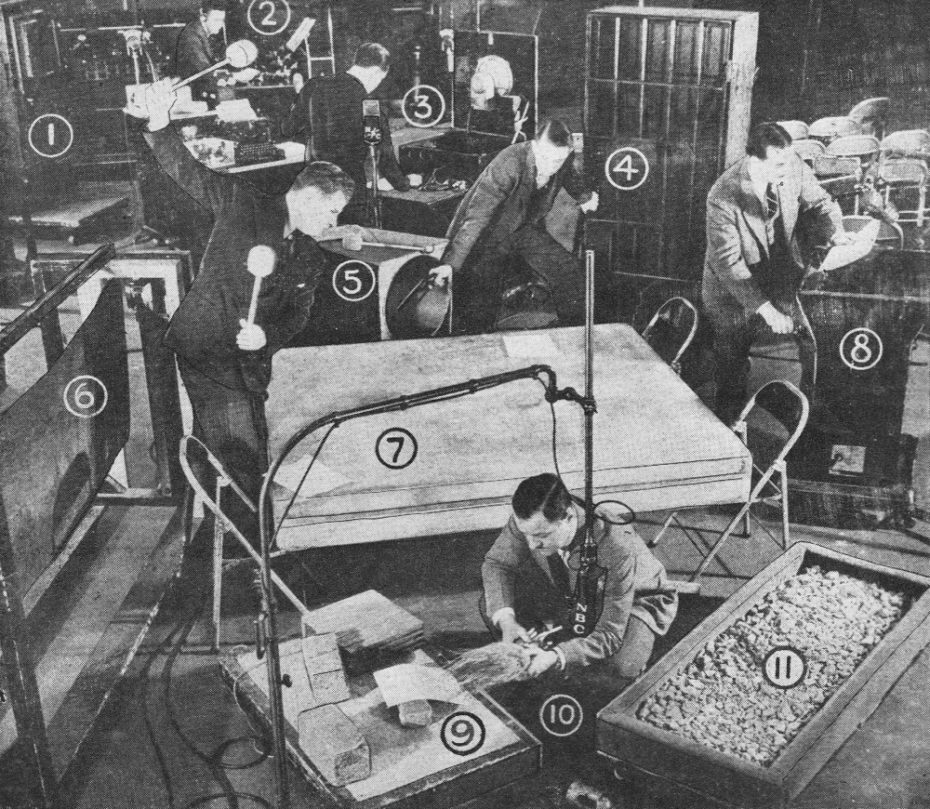

Kisses, and the crunch of a boot; raindrops, and the blow of a fatal punch – they were just a few of the sounds that Foley realized on-set microphones couldn’t really capture. He broke them down into three general categories: moves, specifics, and feet.

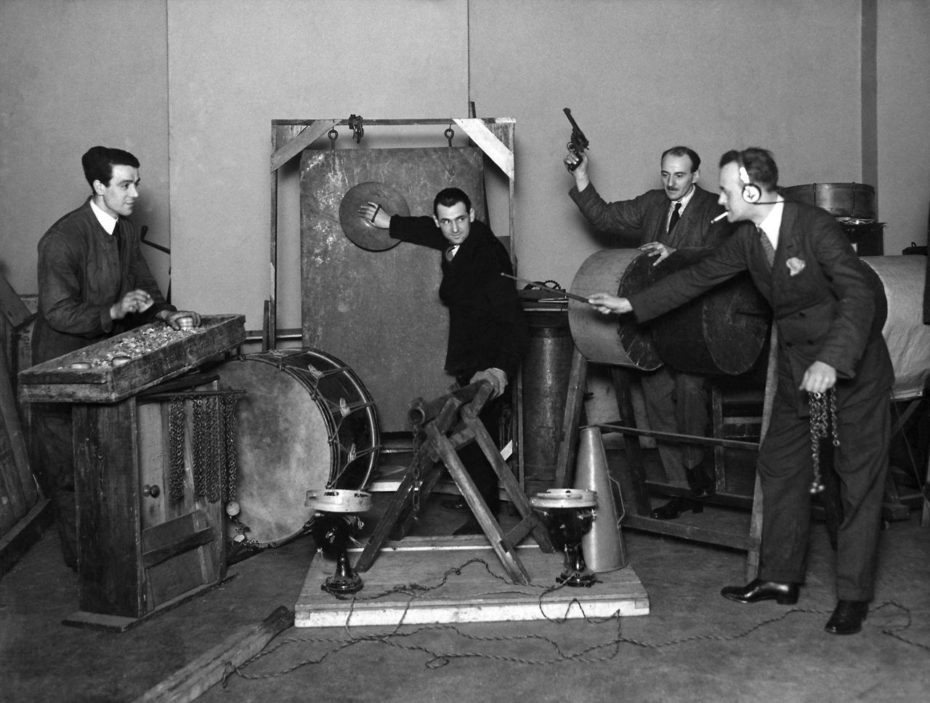

Thin sticks make for great “whooshes,” and a metal rake can sound like a chain-link fence. Corn starch in a leather bag sounds like crunchy snow. Burning plastic garbage bags recreates the sounds of a romantic candle or fireplace crackling, and smashing frozen romaine lettuce sounds like the crushing of bones or ice (we see you, Titanic) – we could go on. The trick to inventing a new foley was to think about the sound you needed in a scene as it relates to specific, sometimes fantastic, visuals, and to separate it from the objects you’d normally associate with it. Which isn’t as instinctive as you’d think.

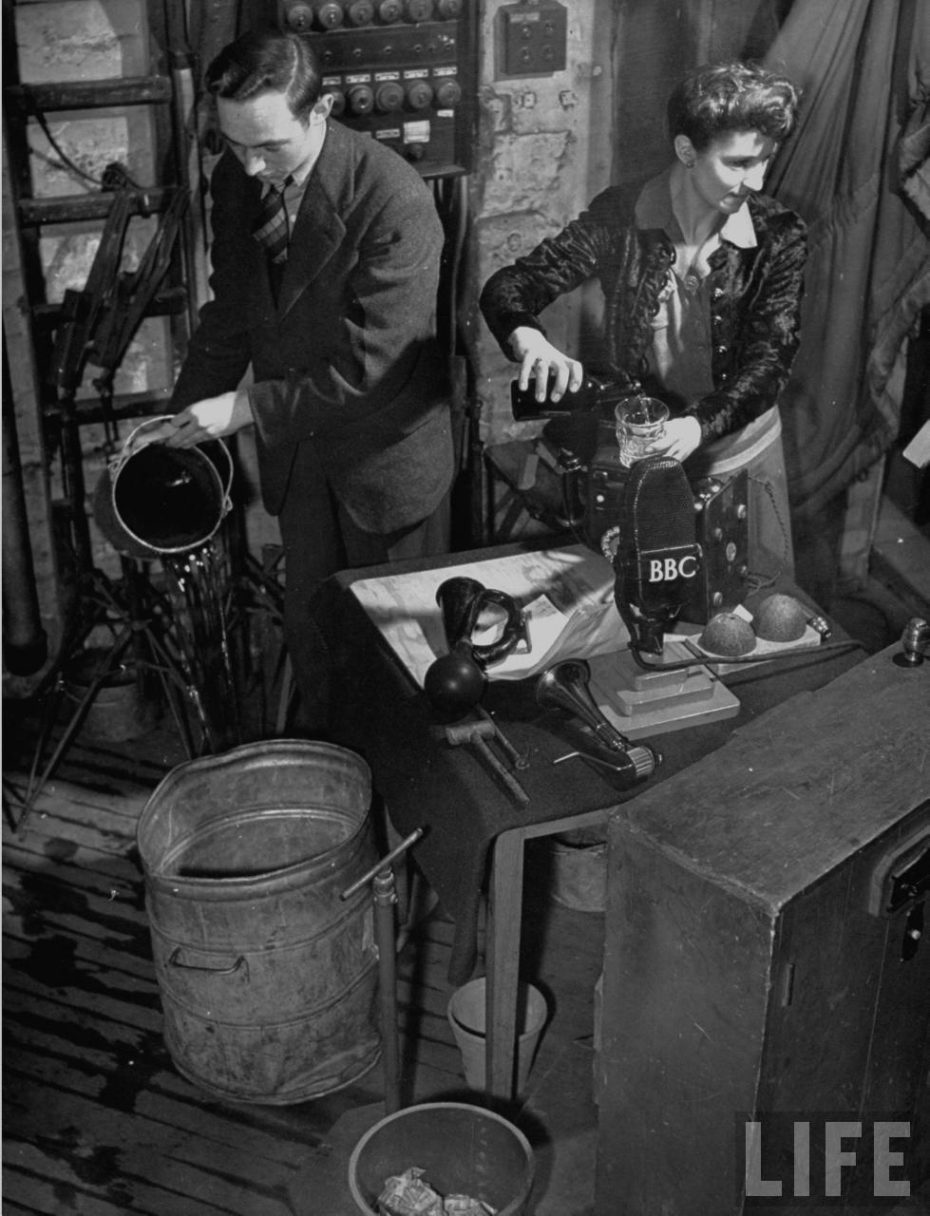

For example, rain is a tricky one. Foley maker Leslie Shatz told The New York Times in a 2012 that “if you really listen to what it sounds like when it’s raining, you can’t use that in a movie: it’s too light and indistinct. I have this recording of pouring water onto concrete, just splatting. It’s a very hard kind of sound.”

In matters of feet, Mr. Foley “walked” in the shoes of stars like Kim Novak, Laurence Olivier, and Rock Hudson, who he said had very “deliberate” footsteps. Marlon Brando, by the way, had “soft” steps according to Foley, and James Cagney’s were “clipped.” The category of “moves,” on the other hand, refers to the sounds of a folded jacket, or a brushed knee – anything really discreet — while “specifics” refer to everything from a peck on the cheek, to an explosion.

At this point in movie history, there are versions of a lot of these sounds, but a lot of them still have to be tailored for every film. Foley-making isn’t just a matter of banging together some pots and pans, or taking a 1-metre stroll in a gravel pit. A foley maker’s eyes are glued to the screen and actions of the character they’re imitating, and in that way, they’re the hidden stunt doubles of cinema’s most iconic scenes.

Have a look at some contemporary foley makers below. Who knows, perhaps it’ll strike you as your next vocation. Talk about a MESSY workplace!