In the frosty forest of Nordmarka, Norway, the seeds have been quietly planted to save the future of the written word. Every year for the next 100 years, 100 famous authors have pledged to each write a novel that will remain unpublished until the 22nd Century, when they will be published as part of the ambitious “Library of the future.” For each work written, a spruce tree will be planted on vast lot, making a new forest. The manuscripts will be printed on paper made from the trees in the year 2114. “I thought it was a wonderful idea,” explained Margaret Atwood, the author of The Handmaid’s Tale, in a video about the project, “It appealed to me immediately.” You see, Atwood has a lot at stake in those saplings. Along with a select few authors, she’s been chosen to write a book that will only be published a century from now. If all goes according to plan, it will unlock a veritable, 100-author-heavy anthology of literary genius by the time we’ve all kicked the bucket. If it sounds like a pipe dream, fret not: we had a chat with the Library Chair, Anne Beate Hovind, about just how one goes about planting a forest of literary giants.

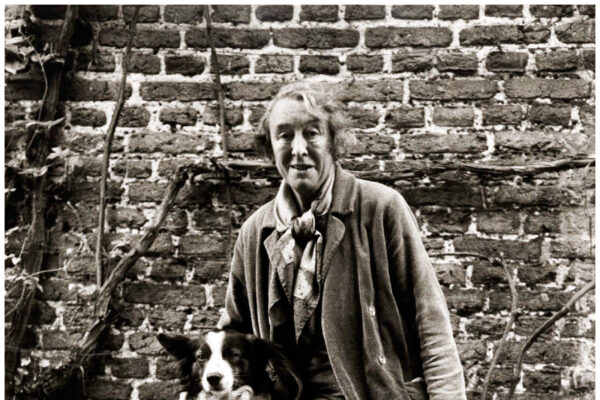

The project was first imagined by Scottish artist Katie Paterson. “We commissioned [her] to propose a work for us that was supposed to be relevant to our urban lives in Oslo,” says Hovind, who worked with project developers Bjørvika Utvikling (in a remarkable marriage of development, sustainability and creativity). “She called me after a week and said, ‘I would really like to visit a forest. And stay there for a while.’ She asked me if I could give her access to a cabin, which is kind of the cliché – but she was right (laughs). I drove her to the middle of the forest, she stayed there for a week and that’s when she said, ‘I know what to do. I have a wonderful idea for this centre in Oslo,’ and I said ‘what is it?’ and she said ‘It’s going to last for 100 years’ and I thought, Oh no. It’s not gunna happen. I was imagining my board, and thought, they’re not going to approve this. I kind of panicked. But they did.”

Paterson’s brain has a knack for dreaming up extraordinary projects. She’s built a live phone line to the sounds of a melting glacier (07757001122), and published a book of prose literally covered in cosmic dust (ex. meteorites, asteroids, etc.) She’s mapped out dead stars, created a light bulb to simulate moonlight, and hung a disco ball that reflects every solar eclipse. In that regard, the Future Library is another feather in her visionary cap: a living artwork that underlines the fragility, and scope, of our humanity. It’s kind of amazing looking back on it,” Hoven says, “because it was such an exercise in trust.” Trust in the property developers to recognise, and support, a green initiative. Trust between Paterson and Hoven to move the project forward, and prepare it for the generation to come. “That in itself is a work of art, I think,” she says.

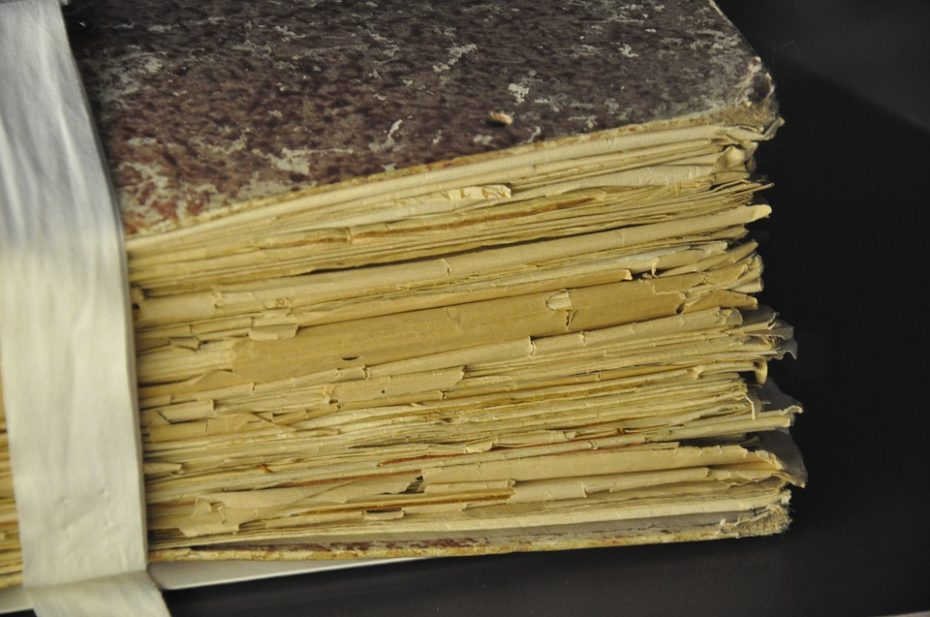

The concept is simple: one year, one new secret manuscript. Other than the title, nothing is revealed about work, which is presented by each author in a moving “Handover Ceremony” before being locking up until 2114 – exactly a century after the project’s ribbon-cutting. During that coming century, the manuscripts will become speculative, prophetic relics for the digital age. Totems for worship, and reflecting upon the written word.

Consider Margaret Atwood’s Scribbler Moon, the project’s inaugural book. “How strange it is to think of my own voice – silent by then for a long time – suddenly being awakened,” Atwood says in her statement on the Library’s website, “What is the first thing that voice will say, as a not-yet-embodied hand draws it out of its container and opens it to the first page?” Luckily, her words will hibernate in good company, as the writers David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas), Icelandic poet and frequent singer Björk collaborator, Sjön, and most recently, Turkish-British novelist and women’s rights activist, Elif Shafak, are also contributors.

But let’s talk logistics. How on earth does one go about putting dibs on a plot of land big enough to plant 1,000 spruce trees? Largely thanks to the developers at Bjørvika Utvikling, who first commissioned the project (in a remarkable marriage of development, sustainability and creativity) the very environmentally conscious city of Oslo (an hour away from the Library), and Norway as a whole. “I grew up on a farm, actually,” Hovind says about the role of ritual in the artwork, “on a farm that goes back 11 generations. My father died when I was very young, and I had to decide whether or not I was going to keep this [family tradition] going. I decided not to.” While Hovind doesn’t ho, she’s tilling our earth in a way that would make her ancestors proud.

As a country, Norway has gained a very eco-conscious reputation. It houses the Svalbard Global “Doomsday” Seed Vault, which preserves millions of seeds in the event of environmental catastrophe – a great idea, but one that also ever so slightly scares the hell out of us. Not unlike the Future Library, which begs the question, just how will humans be doing in a century?

Hovind is optimistic. You kind of have to be, to plant a hundred spruce trees. “That’s why this has been life-changing to me,” she says, “I was reading an article recently about how young people these days, they just ‘turn-off’ [the news] because it’s too negative.” The Library, she says, isn’t here to prod us about the destruction of our natural environment. Not quite. It’s here to give us hope, become fuel to fight it. “Margaret [Atwood] told me, actually, about how she thinks we do really need these powerful new stories,” she says, “about how the world is changing, and we can change with it.”

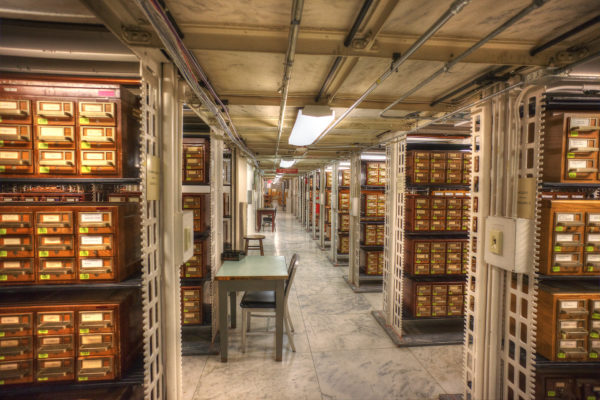

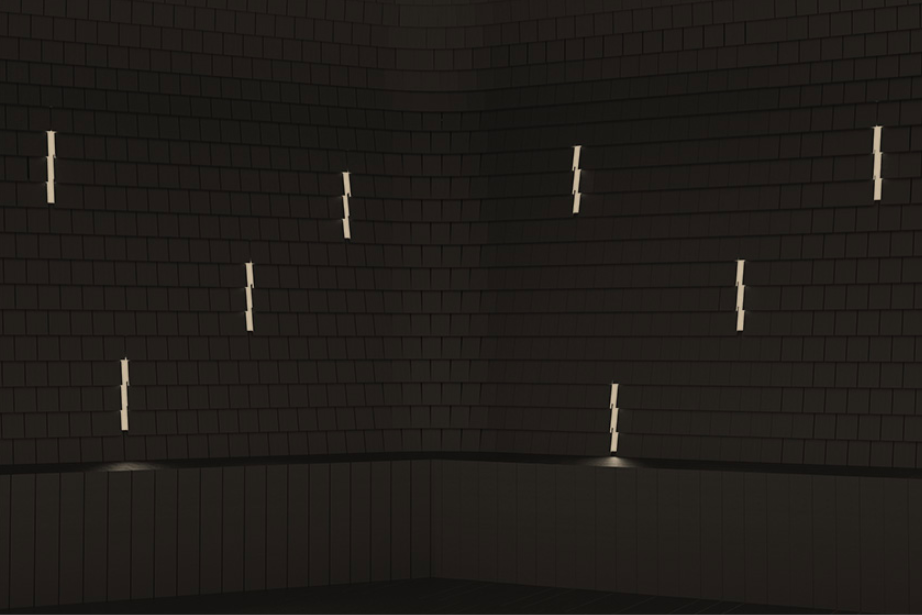

What’s more, everyone is welcome to visit the forest. There’s a free map to the Library online that’s poetically sparse: a single, wobbly line cast out from the coordinates 59°59’10.8″N 10°41’48.7″E between Frognersetern and Frønsvollen. In May 2019, all are invited to attend the Handover Ceremony with the newest author, Han Kang, who won the Man Booker International Prize for fiction in 2016 for The Vegetarian. In 2020, the unopened manuscripts will also be on display in a new “Silent Room” of Oslo’s new public library (currently in development), overlooking the forest and lined with wood from its trees. “The atmosphere is key in our design,” Paterson says on the website about the room, “aiming to create a sense of quietude, peacefulness [and] a contemplative space which can allow the imagination to journey to the forest, the trees, the writing, the deep time, the invisible connections, the mystery.”

It’s hard to make art happen in public spaces. Especially good art. Amazingly, the project doesn’t have a communications team; all the press and interest it receives, Hovind says, is thanks to the power of the project’s narrative. “It’s very complex,” she says, “especially with a project like this that’s so different. Planting a 100-year forest? It’s a pretty out-there proposition. It’s a commitment. And it’s been life-changing for everyone involved.” Atwood, she says, is like family, as are all of the authors. “We’re very close now,” she says, “[Bound] together by one another’s work.” It’s a project about journey over destination, about savouring the processes that build kin. “None of these books will be read by us,” she says, “But they are made by us. We partake in that ritual.”

Of everything humans have invented, writer Jorge Luis Borges said “the most wondrous, no doubt, is the book.” Everything else? An extension of the body, the mechanical. “The microscope, an extension of sight; the telephone, the voice; the sword, one’s arm, etc. But the book? That’s “something else altogether: an extension of memory, and imagination.” We couldn’t agree more.

Visit the project’s official website and Instagram, and enjoy one last musing by Margaret the Great below on why she fell in love with the project…