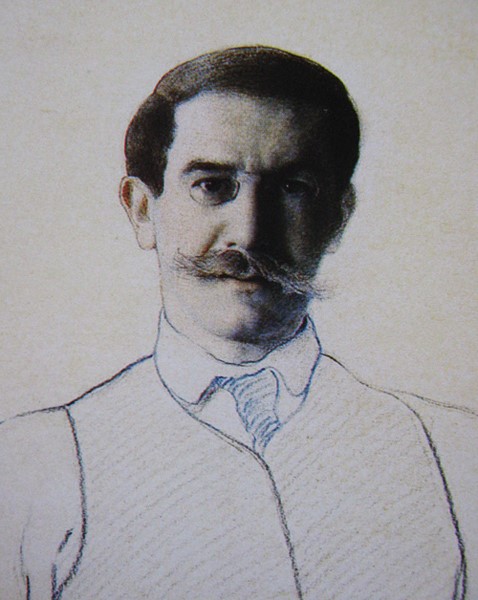

Nineteenth century Russia was restless, and so was Léon Bakst. The young man belonged to a new generation of creatives, one ready to turn Realism on its head with one flick of a bejewelled, utterly fabulous wrist. Today, his name is “a byword for excitement, for colour and glamour” and a radical new approach to the arts spearheaded by the Ballets Russes. Caught between a country in the midst of full social upheaval and his own religious persecution, he was in the eye of the storm. The stage was more than a creative stomping ground, it was a life-raft.

Bakst was born “Lev Samuilovich Rosenberg” in 1866, and grew up in a bourgeois Jewish family in St. Petersburg. He fell in love with the theatre from an early age, as his parents would often take him to shows — but back then, there was no real formation for becoming a stage designer. He enrolled at art school, but didn’t fit in with the crowd.

“He showed no particular leaning to any of the essential core subjects,” says author Elisabeth Ingles in Bakst, “He failed to shine in any field, and overstepped the limits of his teachers’ patience when he produced an altogether too realistic representation of a religious subject” for the prejudiced staff: The Lamentation of Christ, only, everyone had typically Jewish features”.

Officially an art school dropout, Bakst looked to illustrating magazines and children’s books. At the same time, he knew he was walking on eggshells with such an overtly Jewish name, and became “Léon Bakst,” (the surname being his mother’s maiden name). He lived in Western Europe not only to study art, but because, as a Jewish man in Russia, he wasn’t allowed to live outside an area called “the Pale Settlement” of the Russian Empire (“Pale” referring to the latin word Palus for boundary), and wouldn’t be until after the horrors of WWII. The frontier was meant to block commerce between the Jewish population and the rest of Russia, and covered over 1 million square miles.

Luckily, Bakst’s boss knew all the right people, and he mingled with the likes of Chekhov and Tchaikovsky, all while perfecting his style into something no one had quite seen before; it was sumptuous and fresh, evocative of both the Ancient Greeks and Isadora Duncan; Rembrandt, and Velasquez. He became a favourite portrait artist of the last Tsar, Nicholas II, and an art teacher to the children of the Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, as well as Marc Chagall (who he adored for sharing a similar sense of impertinence).

It was a period known in part as the Jewish Artistic Renaissance, because creatives like Bakst and Chagall were eschewing Orthodox lives in the shtetls, or small towns, and busting out onto the Western stage.

It was his designs for the magazine Mir iskusstva (World of Art) that truly opened up his world, and introduced him to Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes.

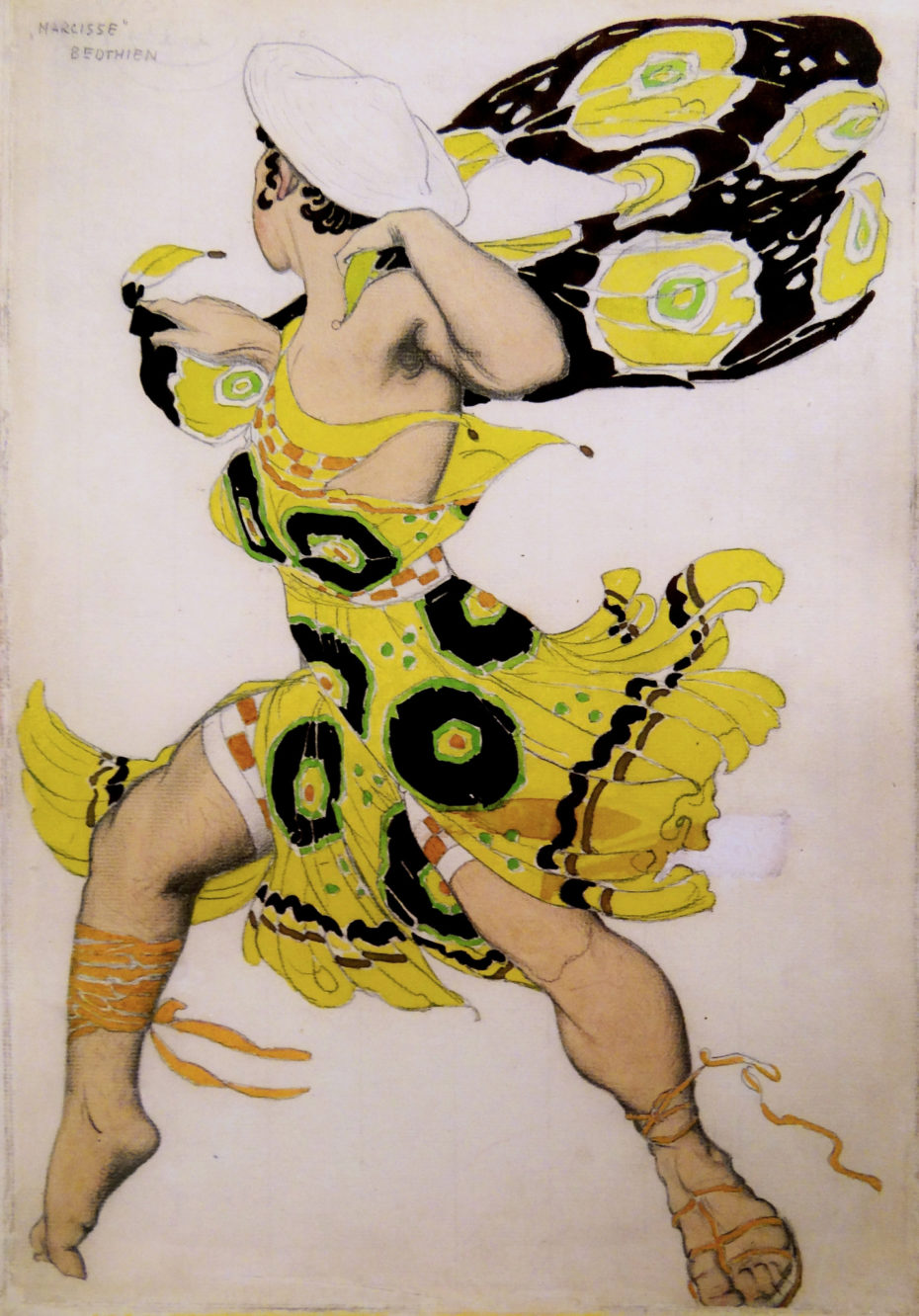

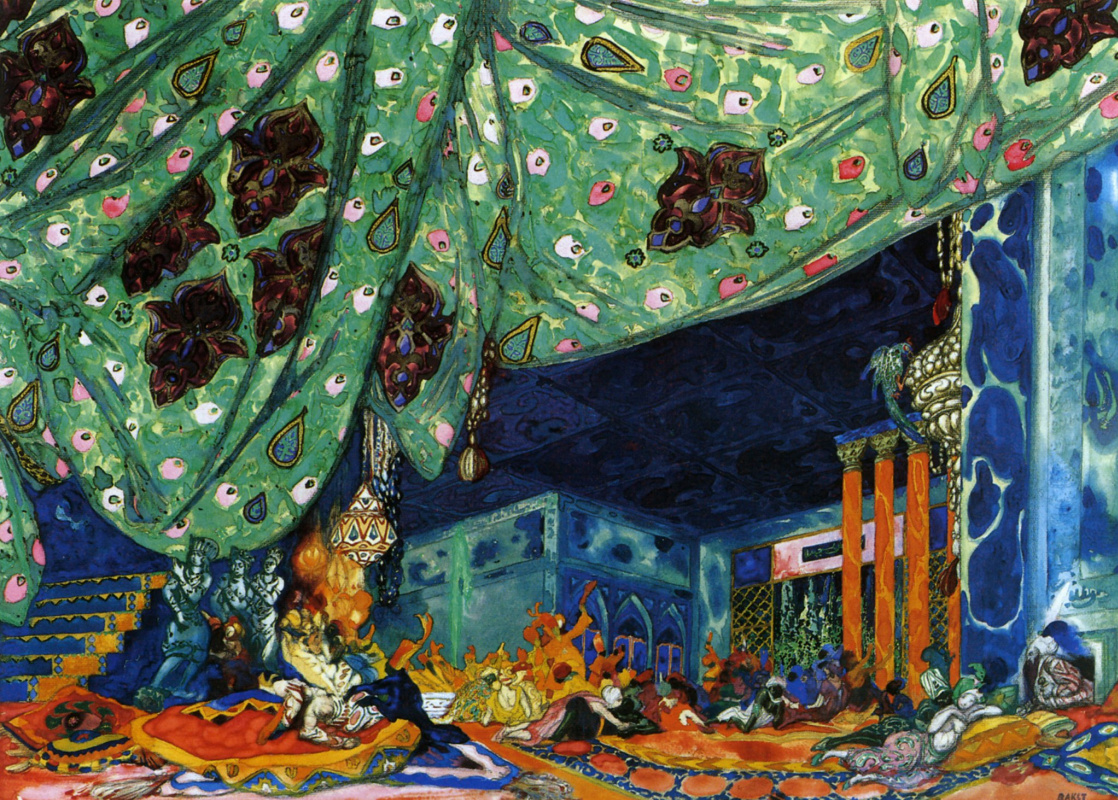

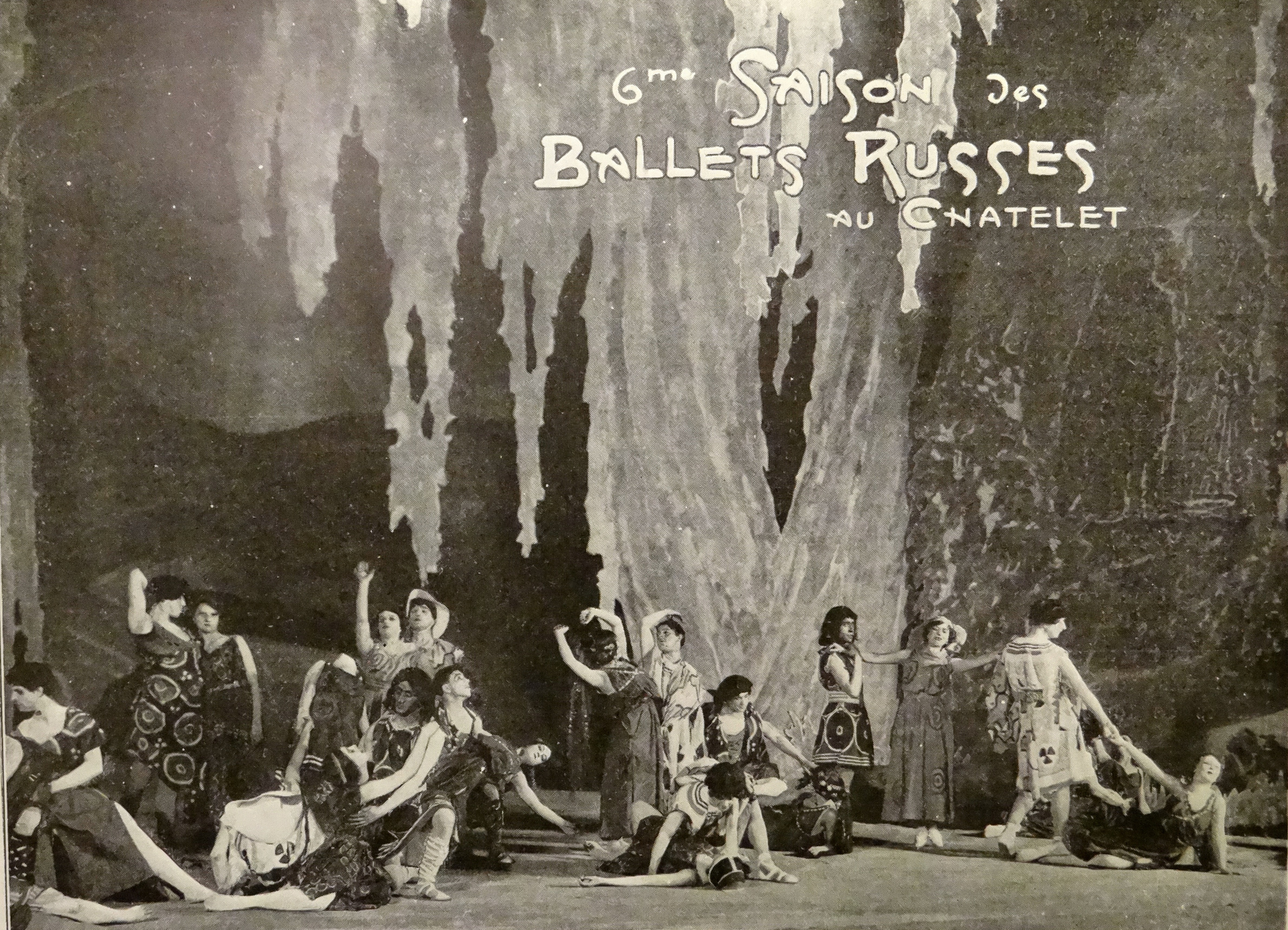

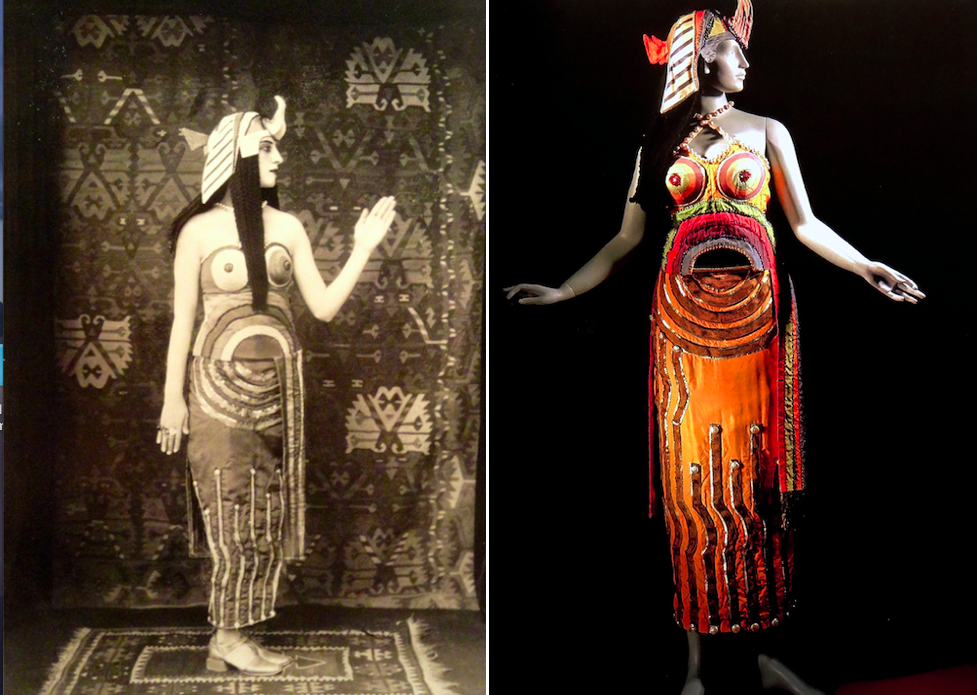

“Bakst’s fame lay in the ballets he designed for the Diaghilev,” said a representative of the Victoria and Albert Museum, “Bakst came into the theatre on the wave of revolution in Russian ballet,” the rejection of “full evening story ballets, like Swan Lake, where the story was told in formal mime interspersed with virtuoso dances and the ballerinas wore pink satin pointe shoes and tutus decorated with appropriate symbols.” In other words, Bakst was here to get weird.

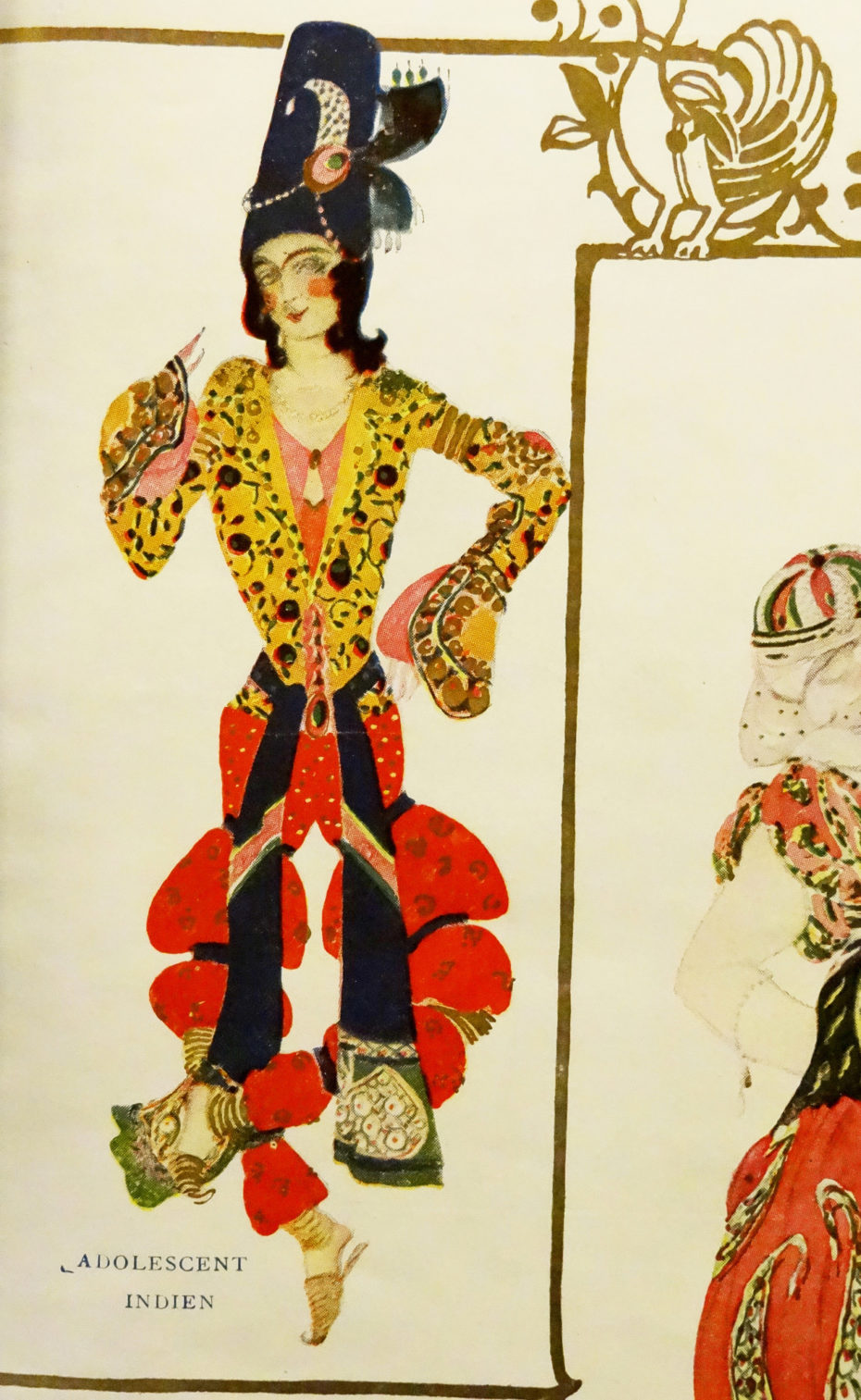

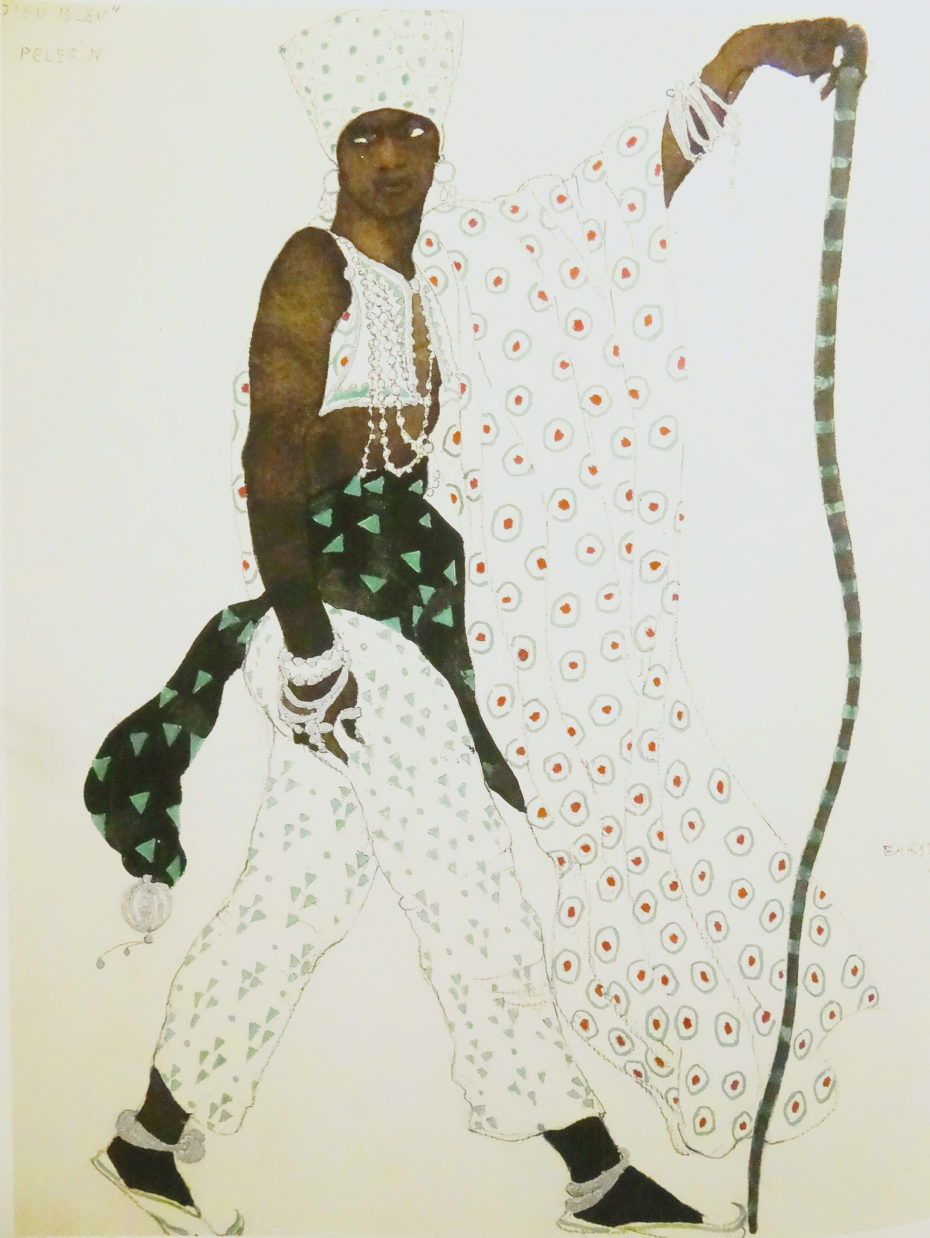

“Goodbye to scenery designed by a painter blindly subjected to one part of the work,” Bakst declared, “goodbye to the kind of acting, movements, false notes and that terrible, purely literary wealth of details which make modern theatrical production a collection of tiny impressions without that unique simplicity which emanates from a true work of art.” For him, colours were feelings (green and blue? Often despair) and no element was too over-the-top for Sleeping Beauty, Scheherazade, or The Spectre of the Rose.

He was a pioneer of Art Nouveau and Symbolism, what with his encyclopaedic knowledge of Antiquity (think Gustave Moreau, but make it fashion) and he worked with great dancers like Vaslav Nijinsky, and Anna Pavlova (yup, the one with a namesake cake).

Even today, his designs push the limits of creativity. A 2015 production of Sleeping Beauty used his costume designs, and a slack-jawed New York Times journalist wrote, “There are 210 [wigs], three times as many as in any other Ballet Theater production. The Queen’s [wig] towers above her like a sheaf of wheat, augmented further by a spray of giant feathers.” Celia Bernasconi, who curated an exhibit in Monaco in 2017 on Bakst, says he really fleshed out a unified, extravagant aesthetic for the Russian Ballet. He understood that there was “a certain dream and fantasy emanating from that scene.”

But in 1922, he broke with the Ballet, would wilt a mere seven years later with the death of Serge Diaghilev in Venice. His next stop was the US, where he admitted to being enticed by the portrait commissions promised by titans like Rothschild and J.P. Morgan offered him. “I have too many assignments on my hands,” he said, “There’s no way I can handle everything. Morgan invites me to America and promises portrait commissions from everyone — that’s nasty […] it’s a dangerous path!”

He even decorated the Baltimore mansion of his friends, Mr. and Mrs. Garrett of Baltimore, with a private, personalised theatre (the only he would ever complete). You can still visit the estate, crowned “Evergreen,” today. It’s offers a rare window into one of the last creative chapters of Bakst’s life…

Eventually, Bakst hit his greatest fear: a burn out. “It’s strange to feel horribly indifferent and almost despondent,” he said about the eventual floundering of his creative drive. His health was also failing, and he died back in the suburbs of Paris in 1924 from lung problems. Yet, the traces of his work on the next century would be more alive than ever, influencing Yves Saint Laurent and his rive gauche collection of 1991, as well as the late, preeminent Hollywood set designer Tony Duquette. He was, quite simply, one of the greatest artist’s to live by the mantra of “more is more.”

Learn more about visiting Evergreen here.