We could play a game here to start off. I could show you a series of ten vintage photographs and you guess which ones were taken in Paris and which ones were taken in Egypt. And to make it interesting, let’s say you get 2 seconds per photo to decide. Ready? Okay go – from the top, start scrolling!

How did you score? 5 out of 10 in Paris? 7 out of 10?

I might have cheated a little, because all of them are in fact photographs of Egypt – except for that last one above, which incidentally, is the only building that looks like it might not be French, but it was taken in front of the Palais de Sciences in Paris at the 1900 Universal Exposition.

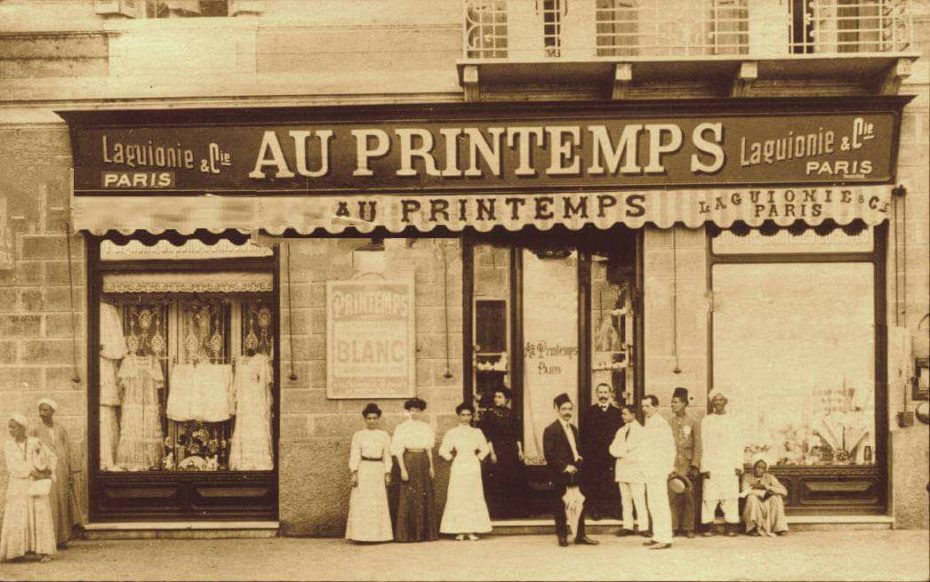

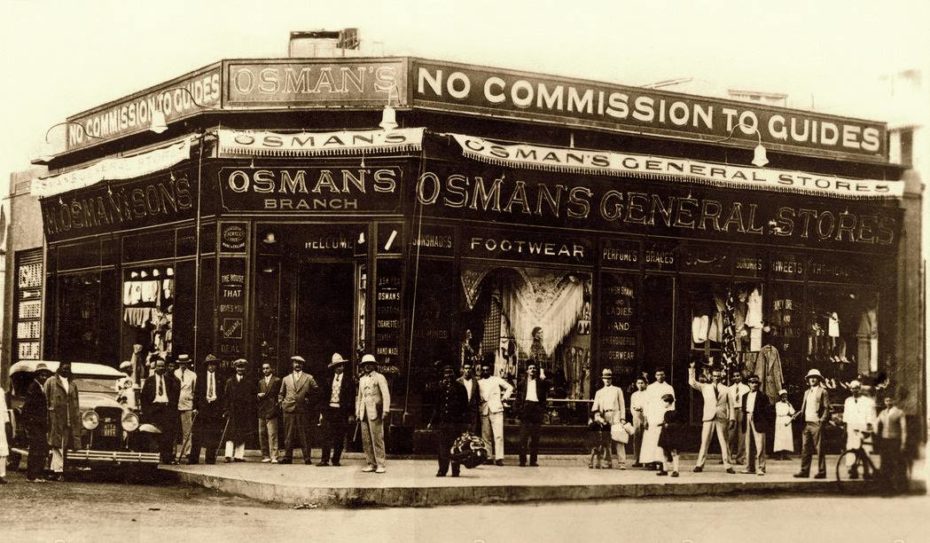

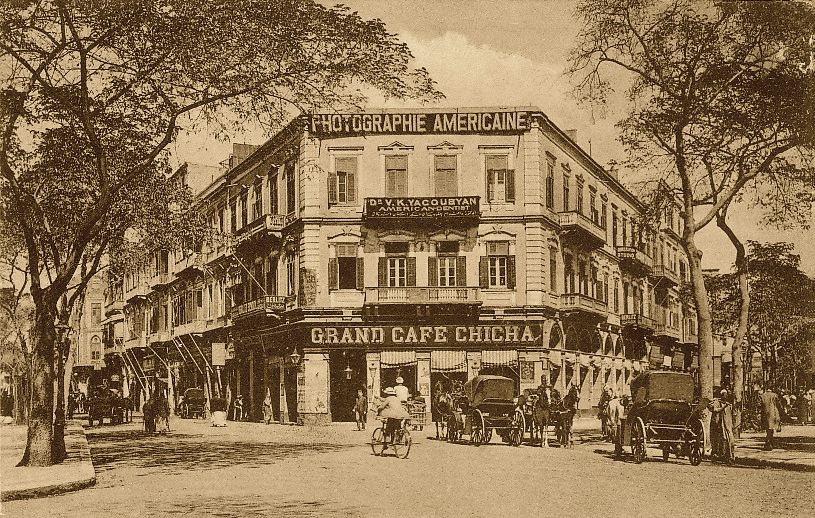

Let’s do a quick run down of what you’ve been looking at. That very first image that looks almost identical to Paris’ Grands Boulevards during the Belle Epoque? That’s Boulak Avenue in Downtown Cairo, 1915. After that, the typical Parisian boutique, perhaps given away by the store clerks wearing the traditional Tarboush hats, was taken in front of the Grand Printemps Store ”Laguionie & Cie”, at the Place des Consuls in Alexandria, 1924. The photograph with the horse & carriages is taken in 1916 at the same address, today known as Manshia Square. The statue that wouldn’t be out of place on Paris’ Place de Concorde is in fact was taken at the entrance of the Khedivial Opera House in Cairo, which was the oldest opera house in all of Africa until the all-wooden building burned to the ground in 1977. The site of the opera has been rebuilt into a multi-story concrete car garage but the square in front of it is still called Opera Square (Meidan El Opera), although you won’t find this statue there today. Then there’s more shots of Dowtown Cairo and Alexandria in the early 20th century, but I think you get the idea that once upon a time, Egypt and France were somewhat difficult to tell apart.

It’s taken until now to realise that China’s replica cities and clone towns we’ve seen popping up in recent years are not exactly a new concept. In fact, it could be argued that colonialists were building replicas of European cities long before the Chinese.

While Egypt was never a French colony, Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition in 1798 on his way to India greatly affected and influenced Egyptian life. During the Belle Epoque, that influence deepened when Egyptian missions were sent to France to specialize in modern sciences and fine arts and French culture left a legacy that’s written all over Cairo, particularly Downtown where their tastes were mainly of a French middle class influence.

I would imagine it began with the hotels, making sure the generals and visiting dignitaries felt comfortable and at home…

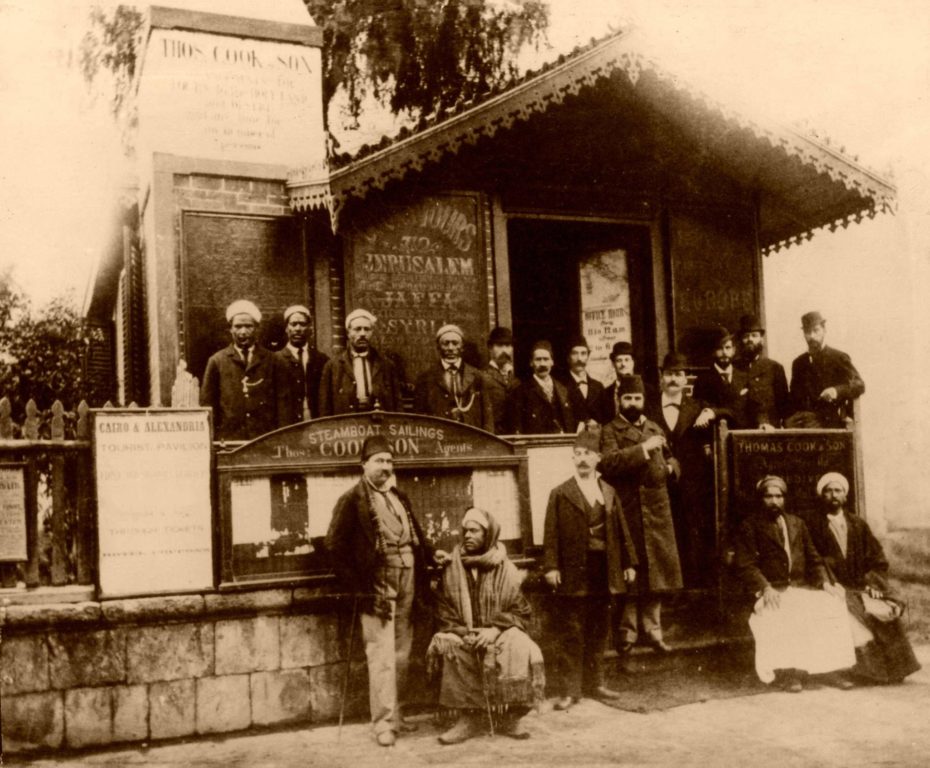

In 1872, Thomas Cook & Son travel agency opened their first head office (below) in Cairo at the old Shepheard’s Hotel (above).

Egypt was one of the first locations tourism expanded to outside Europe and it became a Western playground. You can see how that turned out through the lens of Egypt’s early bird tourists.

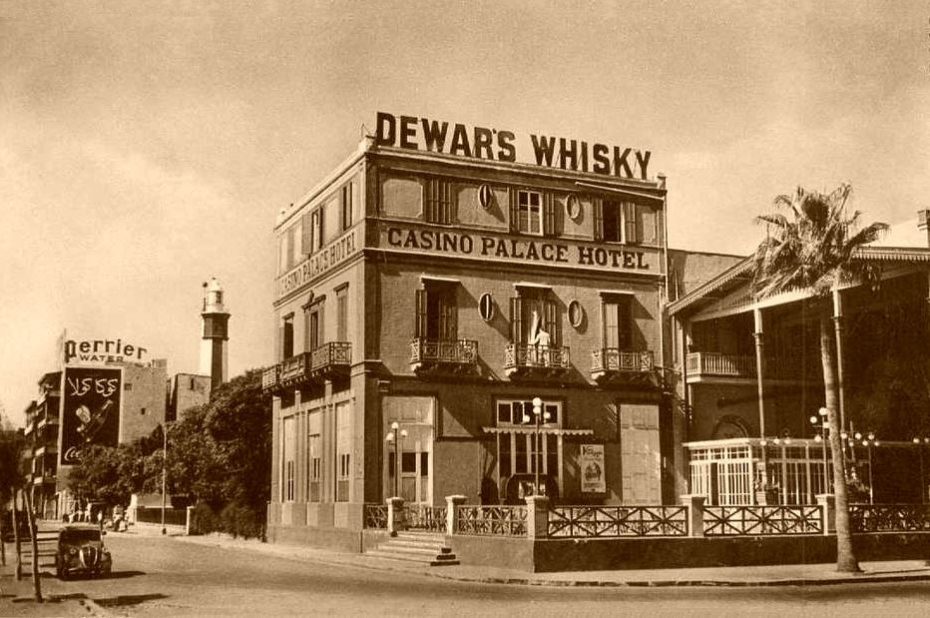

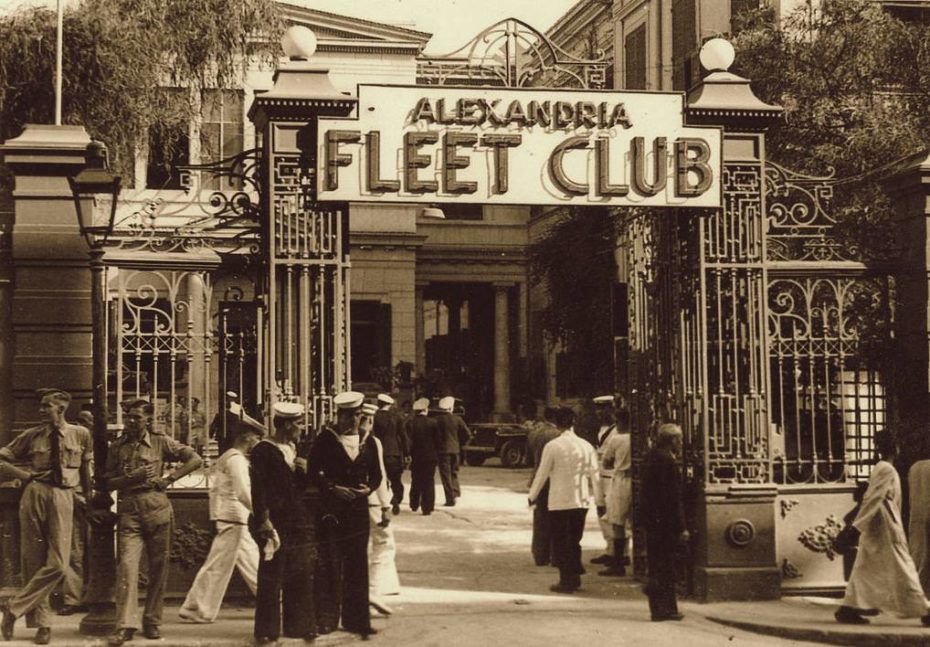

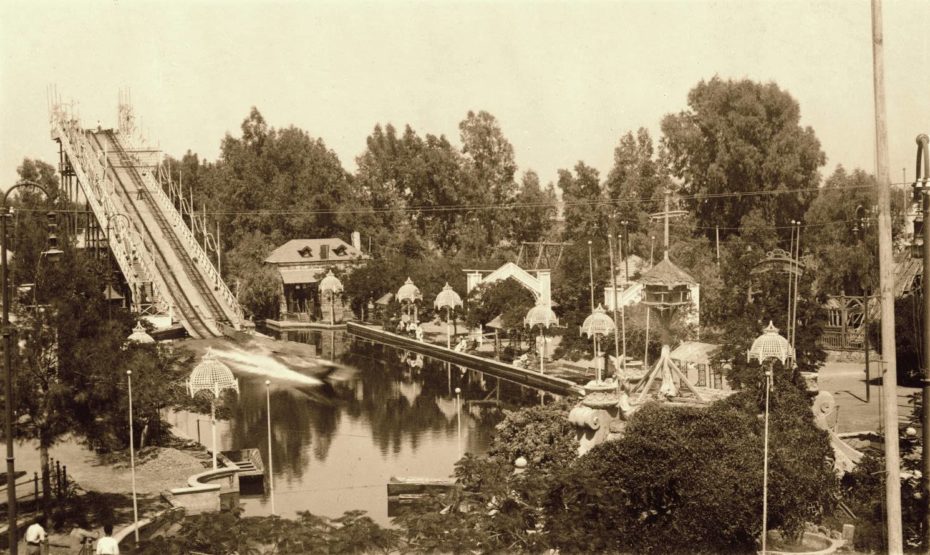

To keep the wealthy Egyptian middle class and Europeans entertained, there were spa resorts and downtown American nightclubs à la Casablanca influenced by Paris’ flourishing jazz scene. They even had a rather fantastic-looking water park which opened in 1911:

It was the first amusement park in the Middle East, but World War I saw it converted to an auxiliary hospital and it never reopened.

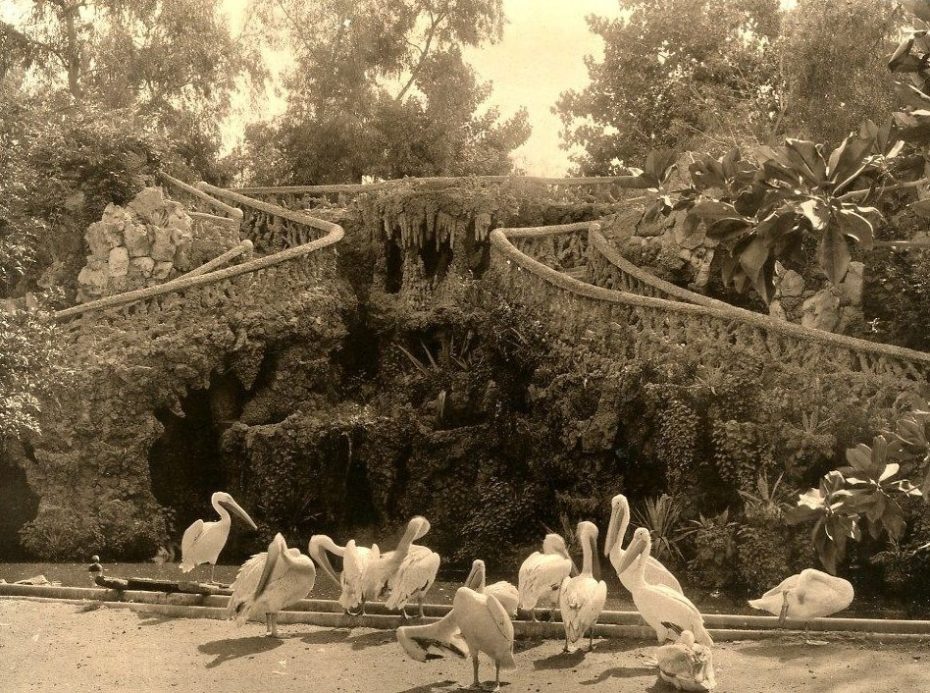

These were the beautiful Azbakeya gardens in Cairo. Book traders once gathered by its gates and there was a theatre that held monthly concerts.

The gardens are only partially present now as two multi-story car parks have been built on large areas of the park.

And is that a charming village in Provence pictured above? No once again that’s Egypt, a historic port north of Cairo. Damietta was in fact once captured by the French in the 13 century and for a short time, it became for a short time the seat of a Latin Church bishop.

The portrait of these two young female students was taken in 1951 at King Fuad I University (today Cairo University). The college was built thanks to the generosity of a royal princess in 1908.

If it wasn’t for the subtly covered faces of these two well-dressed women, you might assume we’d stumbled upon one of Paris’ Belle Epoque fashion houses.

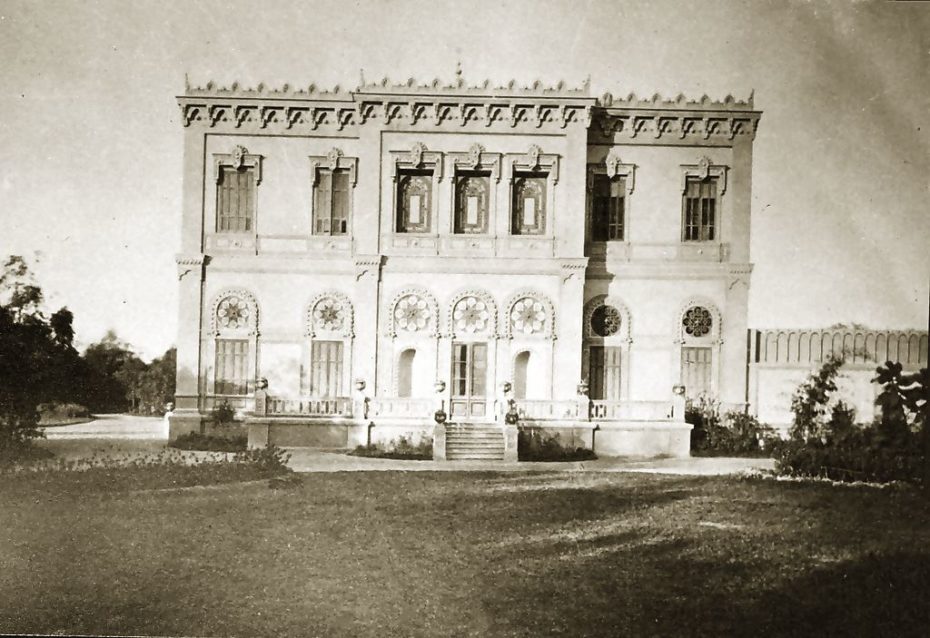

I’d just like to interject here and say that Egypt certainly had its own style of architecture during this period too – and much of it was as beautiful, if not more intricate and ornate than the buildings built by the French and Italian architects that made their mark in Cairo and Alexandria.

Let’s not forget that Europe was equally influenced by Islamic architecture as well. The above palace brings to mind that fabulous technicolor Castello di Sammezzano in Tuscany and what about one of Paris’ most famous landmarks, the Sacré Coeur. Does it remind anyone else of an Arabesque mosque?

This is not the first time I’ve found myself enraptured by Cairo’s Belle Epoque period. You might remember I spoke to a photographer whose passion it was to document the crumbling Beaux Arts ghost mansions of Downtown Cairo.

My interest was reawakened on this occasion when I stumbled across photographs of one of Cairo’s most fascinating abandoned mansions on the Belle Epoque, Prince Said Halim’s Palace, also known as the Champollion’s Palace. The Baroque mansion was constructed in 1899 by the architect Antonio Lasciac and its rumoured the Egyptologist who decoded the Rosetta Stone was living here while he was decoding it.

The palace was taken over by the British in WWI and then became the elite al-Nassiriyah boys’ school before it was abandoned for good and left in decay. It’s one that I keep coming back to time and again in my internet travels, hoping someone might have decided to save it, but alas, each time I check, its situation has not improved (it’s on Google maps here).

If you’re curious as to what most of “Parisian Cairo” looks like today, I suggest you spend a moment with the photographer I mentioned earlier. Xenia Nikolskaya has spent a lot of time wandering the streets of downtown Cairo, discovering the crumbling relics of Egypt’s forgotten Belle Epoque period. And it’s not all bleak. “I actually think my book might have helped lure the attention of Cairenes to their more recent heritage,” she says. “Since the revolution too, the younger generation is trying to reflect on their past and figure out their identity.”

And if you’re curious about visiting Egypt, might I suggest this Nubian Nirvana on the Nile?

See more of Cairo in the Belle Epoque: Monarchy & Dynasty.