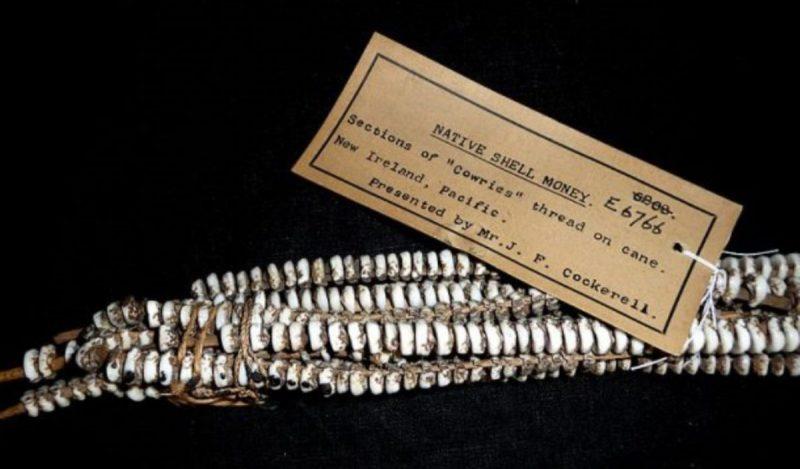

Some of us might recall that day in school when the teacher dumped a bag of cowrie shells on their desk, and decreed, “See this? This used to be money!” Seashells were used as money across the world well into the 20th century, from West Africa to California. And in some parts of the world, shells are still considered legal currency and can be exchanged for real money. Here at Messy Nessy Chic, we’ve become newly fascinated with the idea of footing the dinner bill with a puka shell necklace. The use of shells as a form of currency is one of the most stunning chapters of human invention, so we thought we’d learn a little more about shell money.

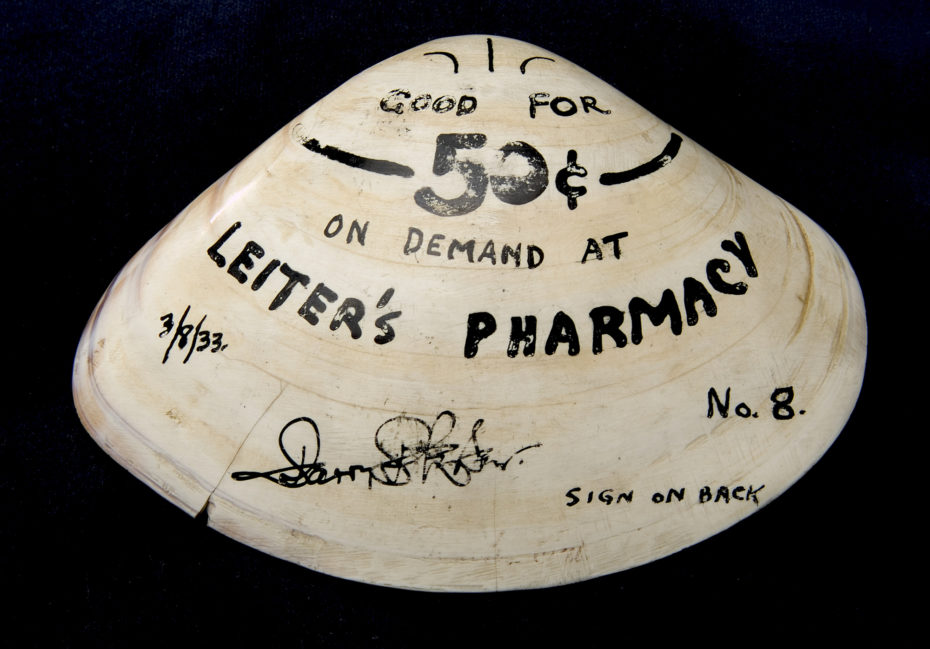

When the America’s banks closed during the Great Depression, communities strapped for cash began circulating their own temporary currency. In 1933, Leiter’s Pharmacy in Pismo Beach, California, issued a clamshell as change, which was signed as it changed hands and redeemed when cash became available again. That shell (pictured top) is now on display at the National Museum of American History.

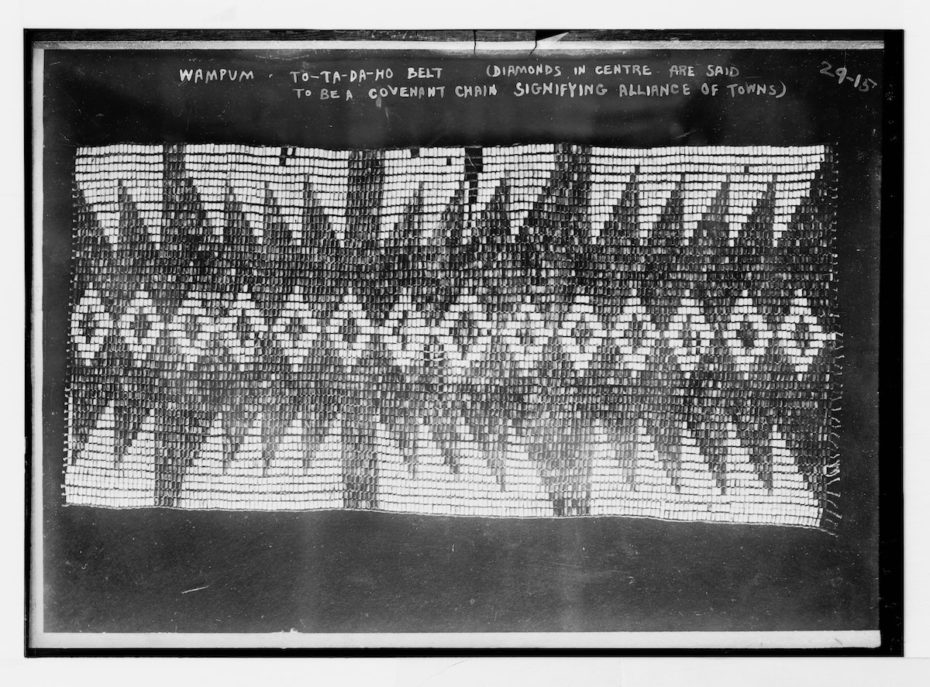

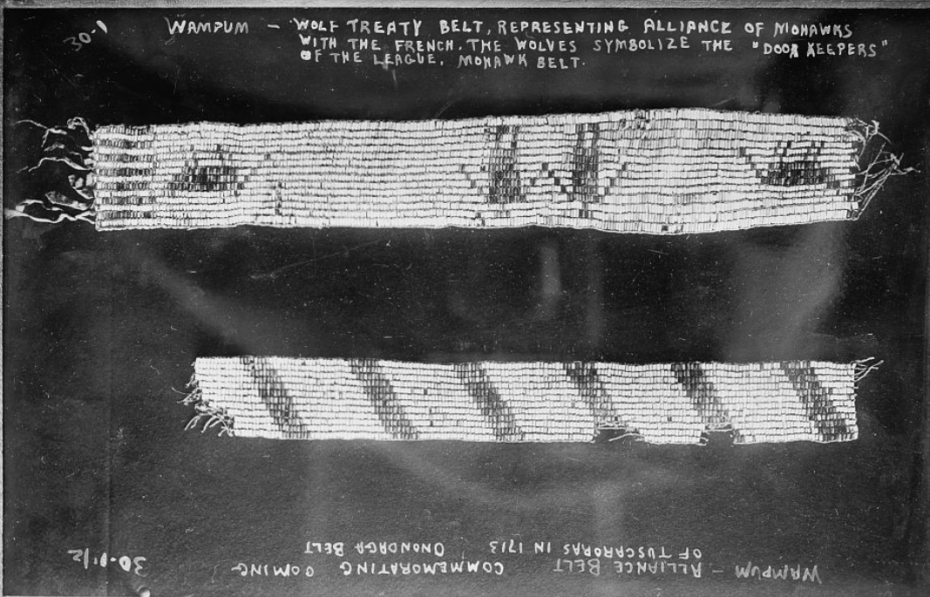

For thousands of years before the Great Depression however, central and southern California natives used olive snail shells, whelk shells and hard clams to make shell money for trade and treaties. “Wampum” is the name of traditional shell beading amongst Indigenous North Americans. The necklaces and belts took ages to make, using whelk shells and purple clams which were polished to a buttery shine. Among the Northwest Coastal tribes, shells were valued for both trade and adornment, and offering one was no lighthearted gesture. Girls of high status wore elaborate tusk shells as part of their dowry. Talk about buying “investment pieces” for your wardrobe…

Below are two Wampum belts, one of which is the famous “Wolf Treaty belt” representing the alliance of the Mohawks with the French. Look closely, and you can see two near-stick figures holding hands:

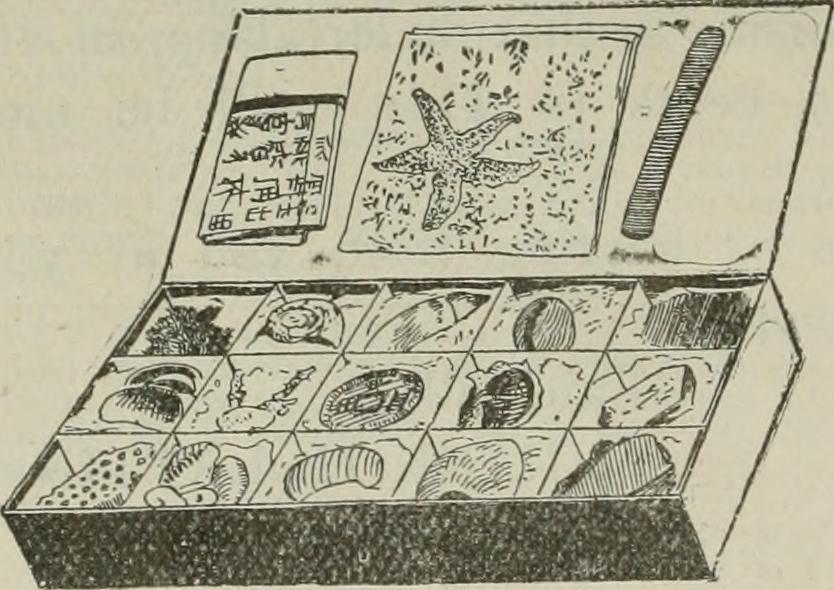

The origins of shell money however, can be traced even further back. China was the first to popularize most forms of currency, starting with shells in 1200 BC, coins in 600 BC, leather money in 118 BC, and paper money in 806 AD.

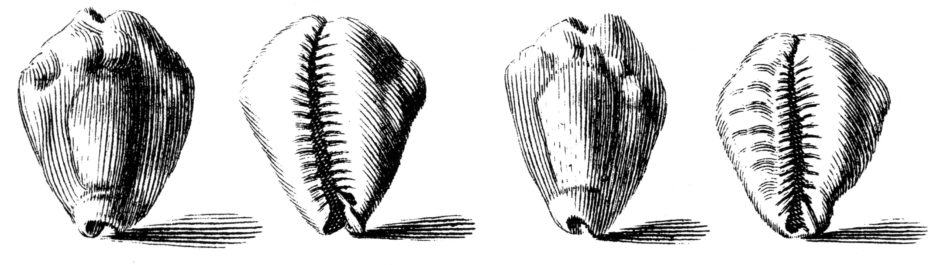

Cowrie shells were so important to the ancient Chinese economy, that today’s current character for “money,” 貝, is actually a pictograph of the specific shell. The shell most widely used worldwide as currency was the shell of Cypraea moneta.

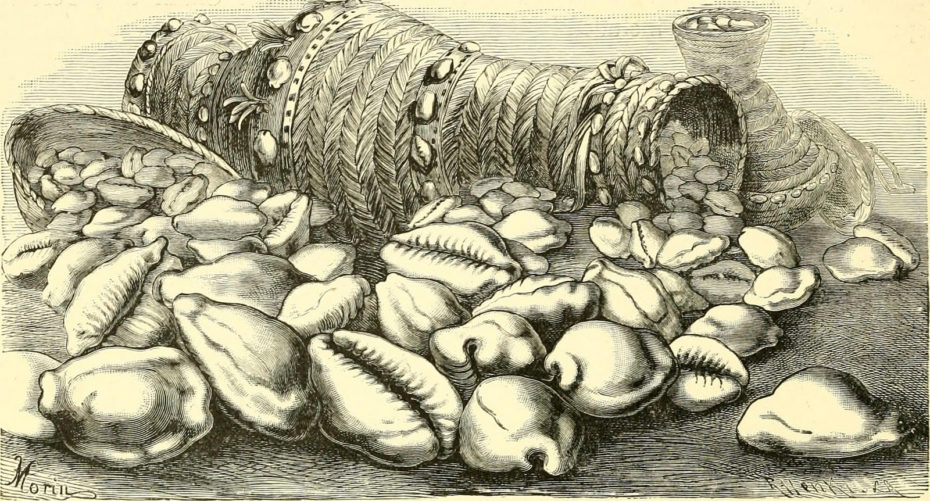

The cowrie shell was one of the most successful and universal forms of currency in the world. Why? Well just consider their appearance: they are instantly recognisable, easy to handle, light to carry, easy to count, non-perishable and most importantly, difficult to forge!

Africa, Australia and the South Pacific also bartered with the attractive shells, which adorned everything from headdresses to canoes depending on the tribe. They took on deep symbolic and ritualistic meanings that have never been entirely lost.

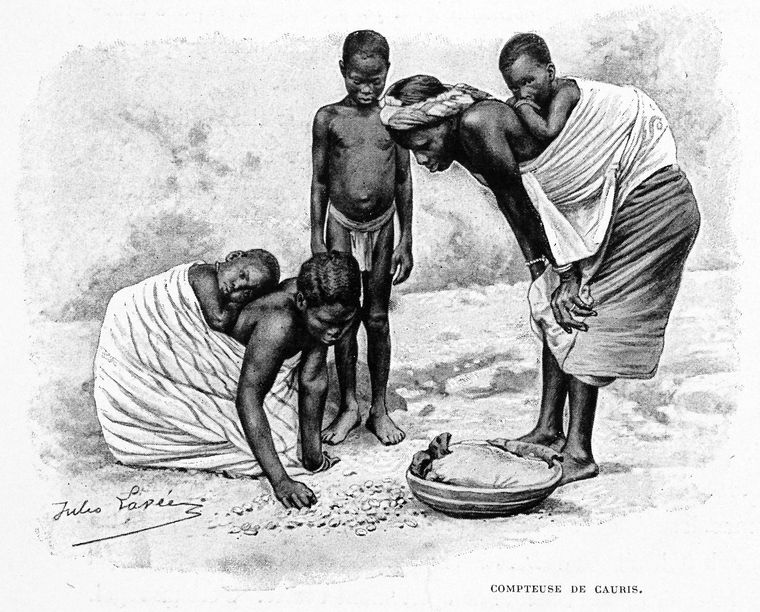

In western Africa, shells were first introduced to the currency by Arab traders. When Dutch traders arrived in Africa, at first they were wary of trading manufactured goods for shells, but the African merchants of Dahomey were also suspicious of the promissory note money. Cowrie shells were widely accepted as money throughout the region that Europeans helped to make them the official currency of choice along the trade routes of West Africa. During the 18th century, shells were eagerly traded for gold, but even more hard to grasp – they were traded for humans, during the height of the slave trade. And try to wrap your head around this: a woman could be purchased for just two shells while a cow would cost 2,500 cowrie shells

Colonizers had a particularly hard time getting the African people to accept new, more centralized forms of currency. For one thing, the West Africans, accustomed to multiple currencies coexisting on the markets, had no problem with the idea of just adding one more. It was the French that prohibited the use of the shells as money at the start of the 20th century, but they had a hard to getting African traders to accept their coins and notes as currency. Keeping the cowrie was a way to defend their independence and their culture, but by the 1940s, shell money had given way to modern currencies.

Communities in the Solomon Islands are actually still using shell currency that is made for and by locals. In fact, if you head over to the Islands on a wedding day, you’ll usually find families exchanging shells mid-marriage ceremony. A 2011 World Bank report says a single strand can be worth 1,000 Solomon dollars (about $120 USD), so imagine how much a veritable curtain of the stuff could cost you. “Of course, shell money is not in circulation as currency anymore,” the World Bank clarifies, “but apart from being the local jewellery of choice, think of it as a sort of Southern Pacific Gold Standard.”

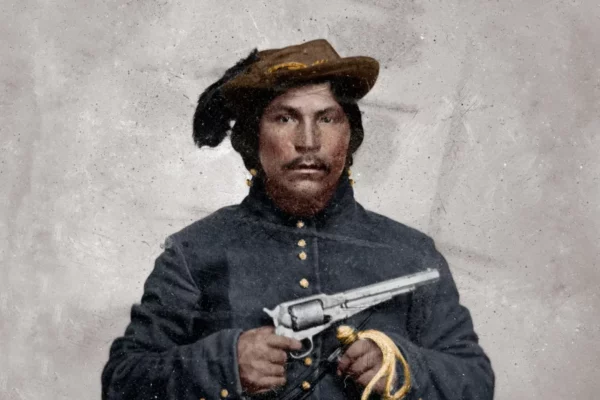

Image by Edward Curtis via the Library of Congress

The strands are made by highly-skilled craftswomen who spend all day diving to the bottom of turquoise lagoons in hunt of the shells, often making journeys hours away from home to find the loot. Today, the women have convinced the World Bank to formally recognise the currency in the hopes of peaking the European market’s interest, and boosting their own local economy. Which brings a whole new joy to the idea of investing your money jewellery.

Photo: Rob Maccoll for AusAID.

Photo: Rob Maccoll for AusAID.

“For the 2,000 Langalanga people in the Solomon Islands, shell money is still fundamental,” says Alexis Jankowski of Pacific Artistan, a site selling ethically sourced shell jewellery made by women in the Solomon Islands, “It is used as a bridal gift, at funerals, and to purchase important items from other tribes such as pigs, canoes and yams.”

But here’s a novel thought. Shells can be exchanged for real money literally anywhere someone wants to do so. All in favour of starting an island community where you can pay taxes with a trip to the beach, say aye!