Not a month seems to go by without a new cultural insensitivity courtesy of the biggest names in fashion. The good news is, we’re finally entering an era that just doesn’t let it slide. As brands begin to learn from their mistakes and respond to demands for change and corporate diversity, we hear the call more than ever to dig into the past and share the cultural context that’s still clearly lacking. Today we’re going to meet Zelda Valdes, the African American fashion designer and entrepreneur who designed and popularised some of the most iconic looks of our time, from the mermaid silhouette adopted by Marilyn Monroe to none other than the Playboy Bunny costume. As in, Hugh Hefner’s iconic bunny suit? Yup – designed by Zelda. But Valdes also broke barriers as a businesswoman, and used her platform to promote inclusivity in fashion decades before the present day industry woke up to the lack of diversity within its ranks. So let’s get fitted (and schooled) by Harlem’s Queen of fashion…

Not to pigeonhole Zelda, but we really think she was destined for couture. For one, her sense of what fit a woman well was almost spookily innate; she only measured Ella Fitzgerald every decade or so, and would just study a tabloid picture of the singer to see what changes should be made to a dress orders that often had to be ready for the singer within three or four days. So not only was she gifted, but also seriously motivated.

She also sewed for women of all shapes and sizes, starting with her grandmother for whom she made her first dress. She was just a kid, but her love for sewing was already in bloom. And her grandmother loved Zelda’s dress so much, she was buried in it. Tailoring ran in the family. That family, by the way, started when her Cuban father fell in love with her mother, an American, in Havana in 1902 and Zelda was born a few years later, moving to America not long after. By the 1920s, a teenage Zelda was juggling one job at her uncle’s tailoring shop in White Plains, New York, with another in the stock department of a fancy boutique. Eventually, she became a sales person at an upscale department store. “It wasn’t a pleasant time, but the idea was to see what I could do,” she said about her climb to the top before the start of the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1948, even before Segregation was abolished, she was able to open up her own shop in Manhattan. She called it: Chez Zelda. The spot was hot, right on Broadway in Harlem, and it was the first business owned by a black woman in that pocket of present-day Washington Heights on Broadway and West 158th Street.

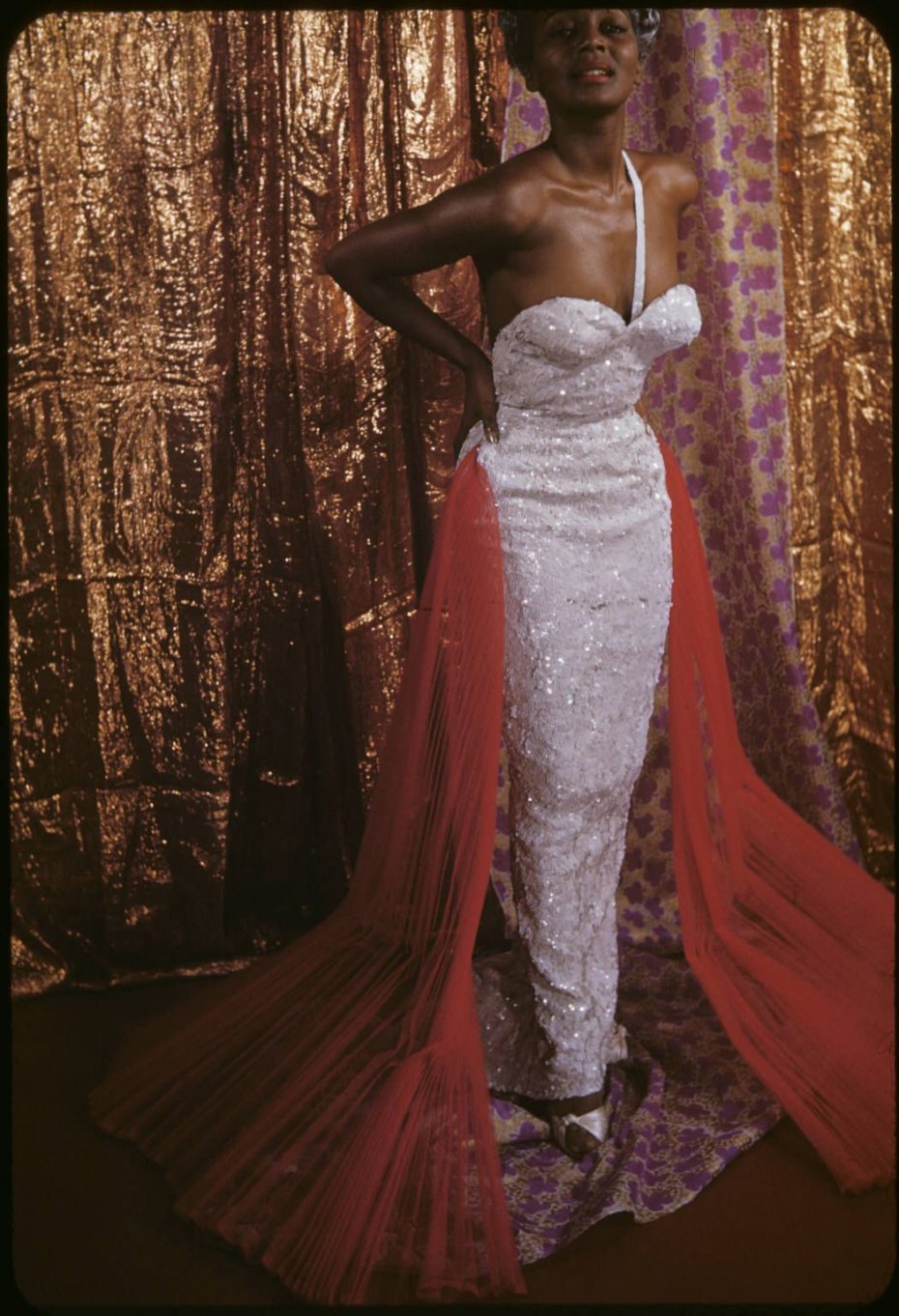

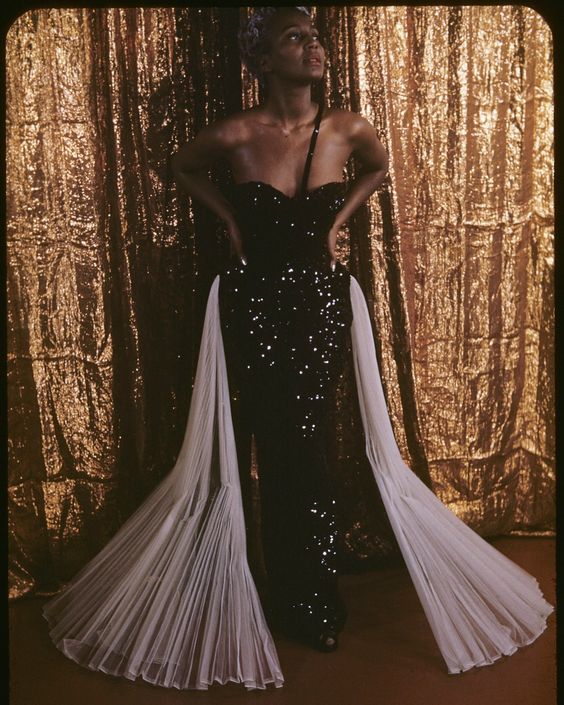

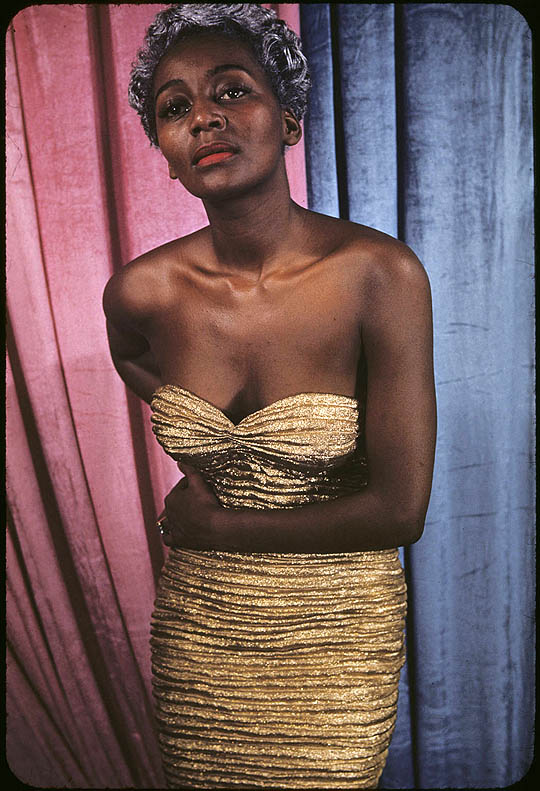

Zelda’s work spoke for itself, but it helped that she was also incredibly candid and at ease with her clients as she elevated their image with her designs. Take Joyce Bryant, for example. The songstress had been known for her pretty cookie-cutter image until Zelda helped her highlight her curves, and off-set her icy hair with a sexier, more grown-up persona (she was coming out with songs like, “Love for Sale” and “Runnin’ Wild”). If you haven’t heard of Joyce Bryant before, she probably deserves her own article, which we’ll save for another day. At the height of her sensational career, much of which was spent fighting discrimination and Jim Crow laws as a black entertainer in mid-century America, she suddenly withdrew from show business early and disappeared from the limelight (and the history books).

Many of Joyce’s gowns designed by Zelda were so tight, it’s said she could barely sit down in them. But that was never the point. The idea was to represent Joyce as a force to be reckoned with in the industry while performing or being photographed, and sure enough, magazines noticed. Soon, she was being called, “the Black Marilyn Monroe,” and the “Bronze Blond Goddess.” Even Etta James was blown away by her look, saying that as she, too, matured as artist, she dreamt of channeling Joyce’s strength and sexiness. “I didn’t want to look innocent,” she said in her biography, “I wanted to look like Joyce Bryant. […] I dug her. I thought Joyce was gutsy and I copied her style–brazen and independent.” Frankly, her looks would still be cutting-edge in any fashion zine spread…

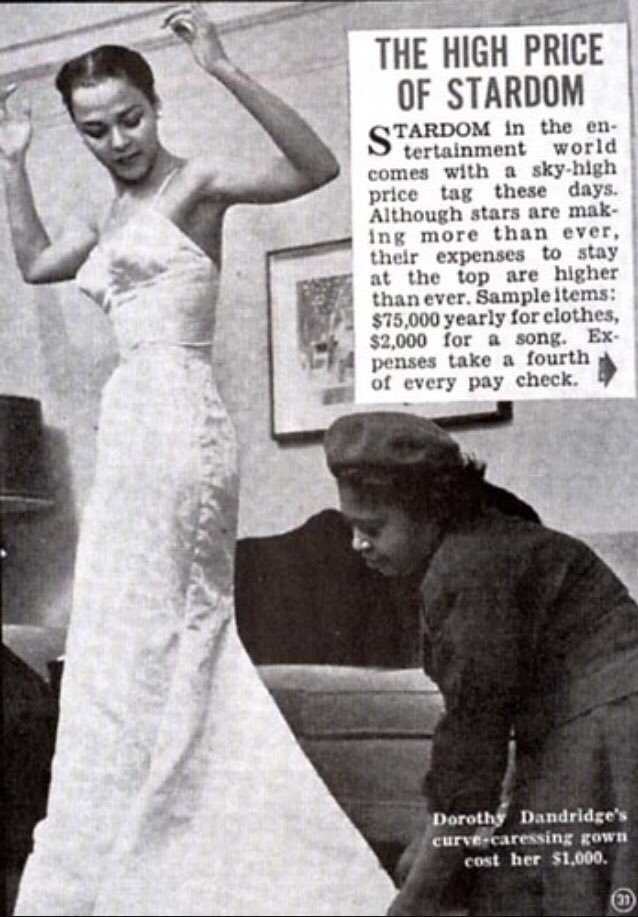

Chez Zelda was the dressing room for some pretty big-name clients. When Eartha Kitt or Marlene Dietrich called, she was ready. Dorothy Dandridge was also a faithful client, as well as Gladys Knight. Mae West knew Zelda Wynn Valdes was the only woman who could make each dress tighter, and more elegant than the last.

She designed many iconic Mae West gowns but history failed to credit her as the creator behind the Hollywood star’s signature look. All of these women, dressed in Valdes’ figure-hugging flared gowns helped popularise the “mermaid dress” which became Golden Age Hollywood’s silhouette of choice, particularly for iconic actress Marilyn Monroe.

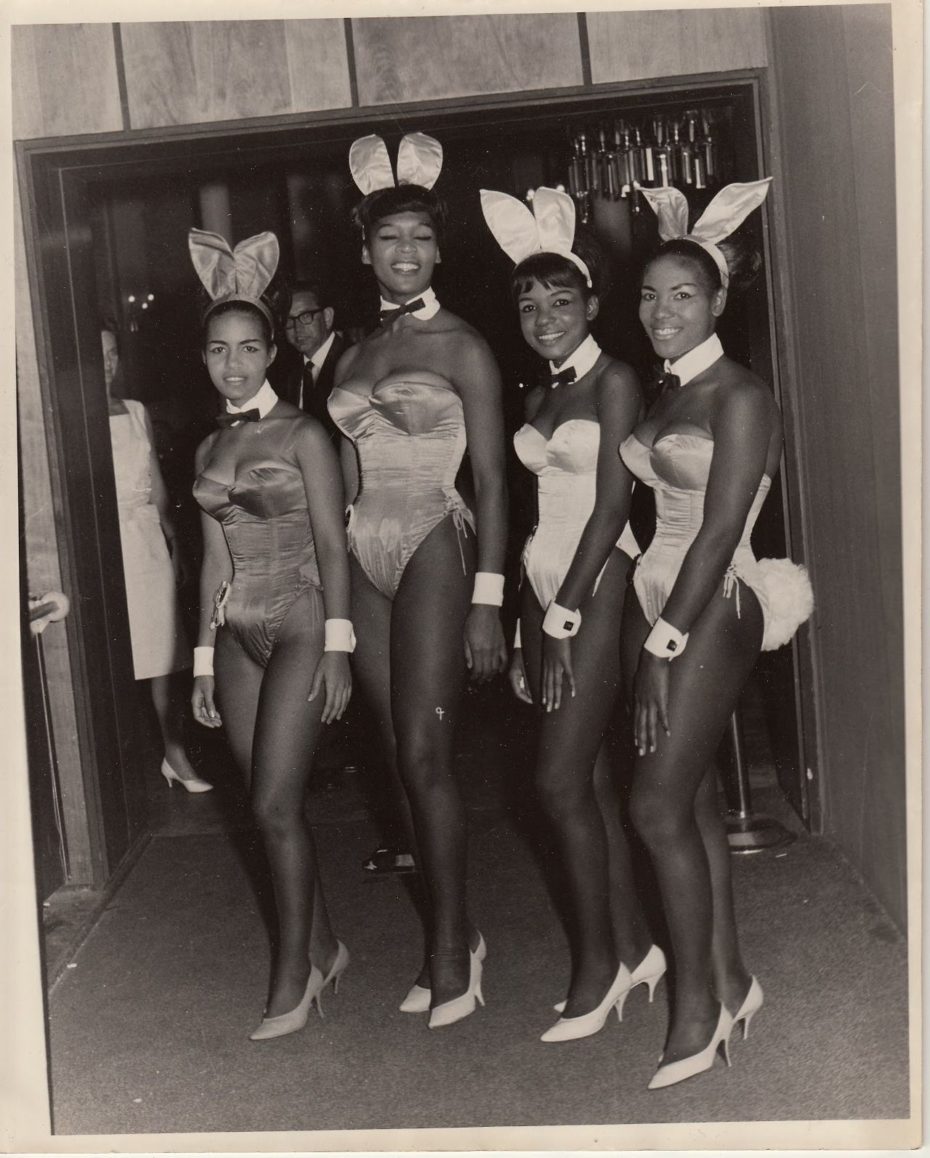

Then, there was Hugh Hefner, and the creation of what is arguably one of the most internationally recognisable outfits on our planet. As the story goes, Hugh approached Zelda to apply her skills for sexy craftsmanship to the outfits of his new club’s “bunnies.” Latvian emigrée Isle Taurins had her hand at it a few years earlier, but Hugh wanted something that didn’t just look like a swimsuit. It became the first commercial uniform registered under the US Patent and Trademark Office, and premiered in 1960 with the opening of Hugh’s club in Chicago.

By 1952, Zelda had moved to Midtown Manhattan with a talented staff of nine. In a matter of years, she’d gone from stocking in the back-room of a boutique, to charging $1,000 a gown – that’s about $10,000 today. Remember: this wasn’t just fashion, it was couture.

These pieces were made with the finest satins, crystals, and beads in the world, and shown not only to those who commissioned them, but displayed at black community charity drives at Zelda’s request.

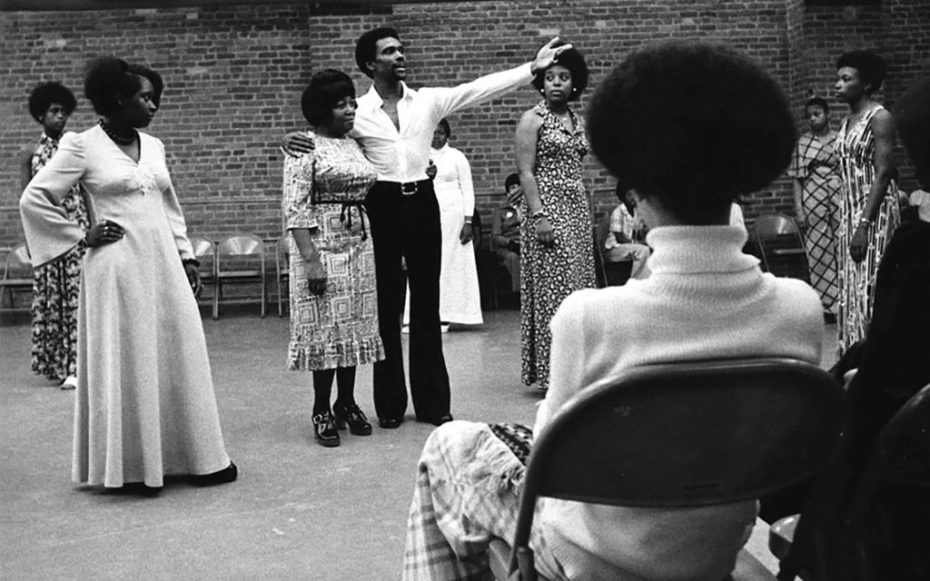

Zelda’s later years also didn’t see her slow down, even though she formally closed up shop in Midtown in the 1980s. At this point in her career, she channelled her know-how into the next generation of black creatives as a teacher and director of the fashion and design workshop of the Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited. She also co-founded the Harlem Youth Orchestra in the 1960s – amidst all her other talents, we neglected to mention Zelda was trained as a classical pianist.

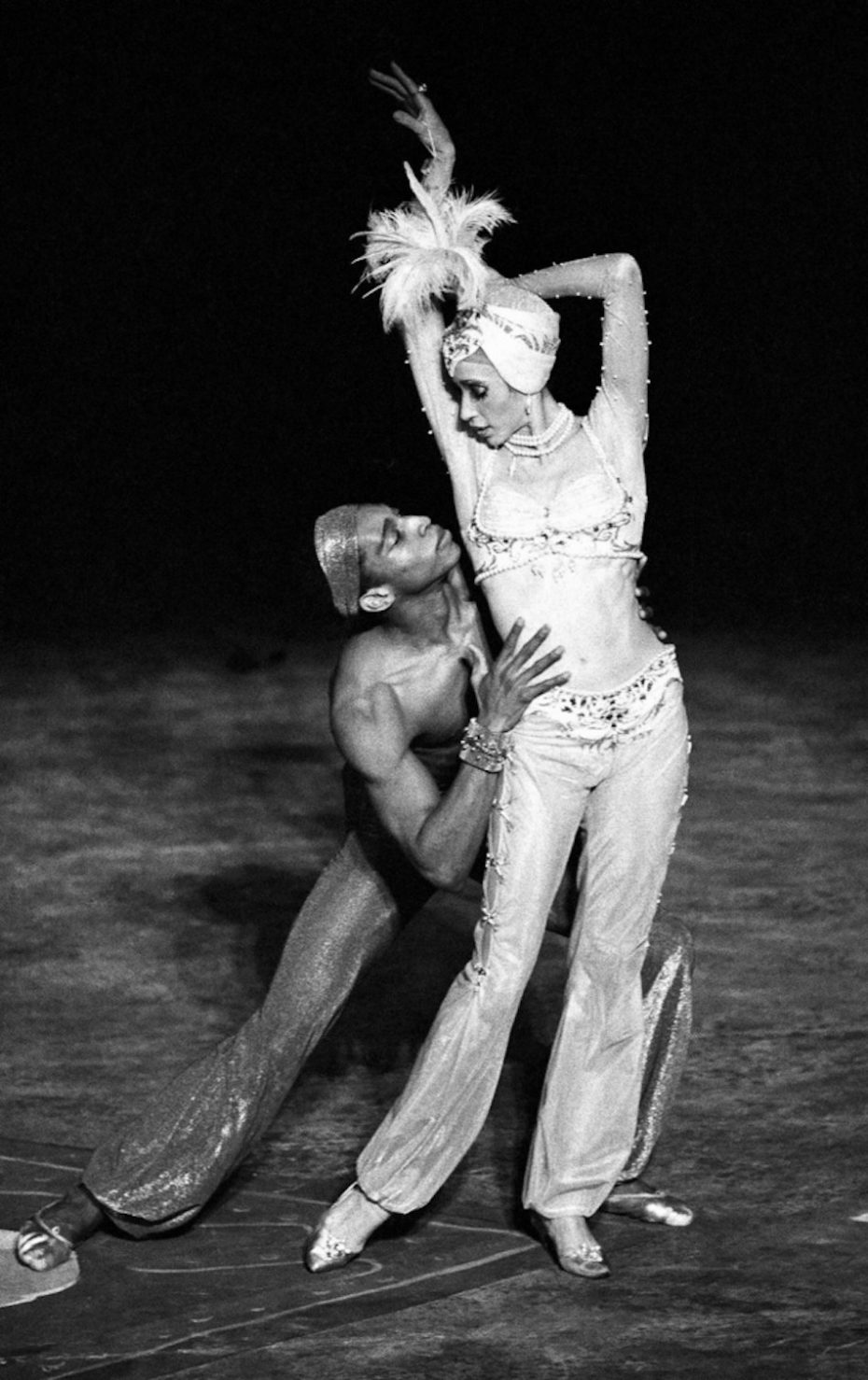

One of her most exciting partnerships didn’t even come until the 1970s, when Arthur Mitchell launched the Dance Theatre of Harlem. It was new and exciting territory for Zelda, who designed groundbreaking costumes for almost 100 productions over the next two decades.

Aside from being gorgeous, they were also – finally – ballet costumes made for black women; instead of slapping standard baby-pink tights on the dancers, she dyed each and every pair to match the performer’s skin tone. When she finally stopped working, Zelda was 96 years old, and left behind so much more than our dream closet. She simply ticked off every box on our inspirational list.

As a black woman in business, she busted through the glass ceiling. Then, as an accomplished, self-taught black designer who had mastered the industry, she made the time to foster the talents of the next generation of Harlem creatives. While Zelda may no longer be with us (she died in Harlem in 2001, aged 96) her legacy surely deserves a seat “in spirit” at the table as the fashion industry looks to the black community for guidance at the start of a new movement calling for change and inclusivity.

There are so many lessons we can learn from her life and work ethic, lessons echoed by legendary underground tailor turned American high-fashion designer, Dapper Dan. The Harlem-based designer, featured on Messy Nessy Chic back in 2013, is currently working with the Italian fashion house Gucci on a global program called Changemakers, which supports industry change following a recent blackface controversy that prompted the company to announce a longterm action plan for diversity and inclusion. “This does not end with Gucci, it begins with Gucci,” declared Dapper Dan on his instagram account this week.

As further changes are promised, we can all continue educating ourselves while elevating heroes and teachers who paved the way for underrepresented minorities. As always, we’ll keep looking for their names and sharing their stories with you. Zelda Wynn Valdes, Dapper Dan, Ann Lowe. Who is Ann Lowe, you ask? She designed Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress but never got public credit for it. She was the first African American to become a noted fashion designer, ran a Fifth Avenue store and sold in top end department stores, but was rarely paid the fees she asked of her clients. As a result, Lowe’s company suffered.

Update: The New Yorker has a great podcast on Anne Lowe, which you can listen to here.

Being able to name history’s black fashion designers shouldn’t be this hard. But to leave you with some words from Dapper Dan that can speak to us all: “embrace change” and “take advantage of the chance to learn”.