Watanabe Katsumi was the king of treading lightly. As a drifting photographer, his lens was a stealthy observer of Tokyo’s red light district, snapping hundreds of photos of its drag queens, gangsters, prostitutes, and other fringe society members in the 1960s and 70s. Few dared enter the underbelly of the city like him and the treasure trove of images he’s left us with today are a gorgeously gritty archive of stories and places that history often sweeps under the rug. Curious about finding “vintage” Japan and how we might stay true to our “Don’t Be a Tourist” motto in its busy capital of neon-lit skyscrapers, we realised Watanabe Katsumi makes the perfect insider guide to discovering the secrets of Tokyo’s underworld…

First, let’s get the lay of the land in Kabukicho, the once seedy neighbourhood in the Shinjuku ward of Tokyo, where the photographer’s subjects reigned supreme. Most of this area was blown to smithereens in the Spring of 1945 when the US Army dropped hundreds of bombs and over a thousand tons of incendiaries on urban areas of Tokyo in a single night. The Great Yamanote Air Raid is somewhat a forgotten historical event often overshadowed by the H-bombs. More than 100,000 people were killed in the firebombing inferno and 15.8 square miles of Tokyo was burned to the ground. In the aftermath of World War II, the area was designated to host an elaborate new centre for a “Kabuki” theatre, which is essentially a historical and traditional Japanese dance-drama in five acts – somewhere between Broadway and Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. The “Kabuki” theatre project however fell through, but the name stuck. A black market and makeshift tenement-style houses rose up amidst the devastation instead. From contraband to everyday goods, you could buy anything on the black market that a heavily rationed economy prohibited. Everything was on the menu, including sex.

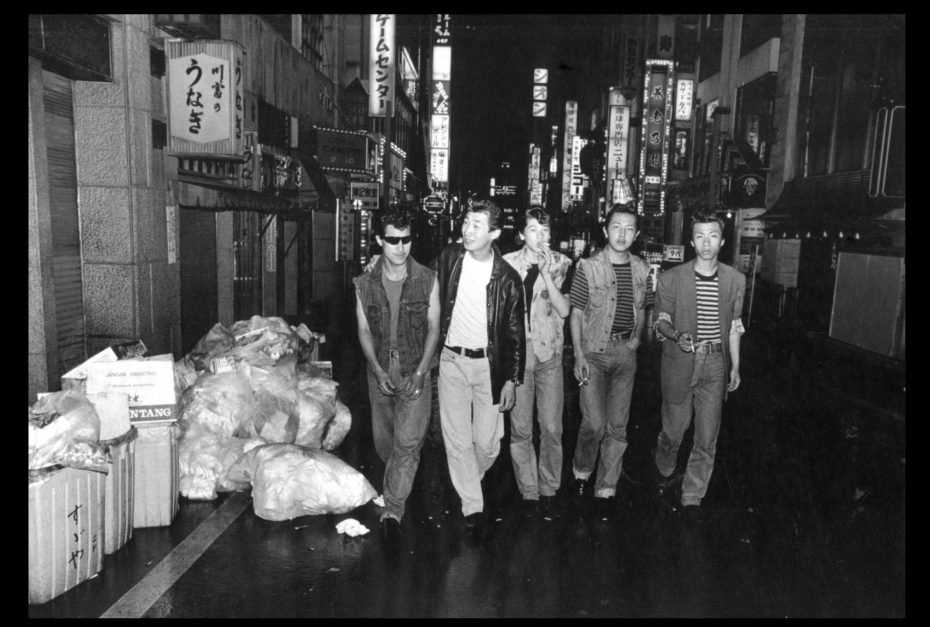

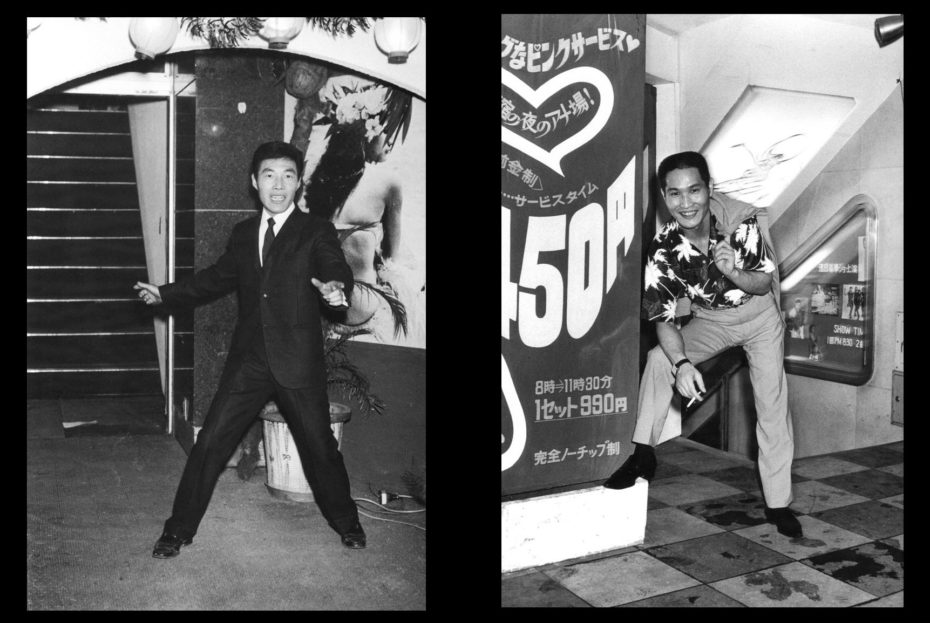

Kabuki became a place for prostitutes to operate in makeshift brothels and Yakuza (gangsters) to break bread in the nomiya (small counter bars) that dotted every back alley. The bars were so intimate, they could only cater to a handful of customers at a time, making them ideal for mob meet-ups and social gatherings of a dubious nature.

In 1949, the American commander of the Allied occupation ordered the dismantling of the black market stalls and brothels, forcing the Tokyo demimonde to disperse and find smaller, less-noticeable pockets of the district to operate in. Today, the Kabukicho district still caters to naughty nightlife, albeit with a vibe that’s more Blade Runner than anything with its sea of digital billboards. The Golden Gai stretch, however, is the only part of that old red light district that survived, relatively untouched, reminiscent to the Tokyo that Watanabe Katsumi captured. It’s also got about 200 little bars crammed into its handful of alleys:

The Golden Gai area still remains incredibly tight-knit and not always keen to let in tourists or non-regulars (you’ll quickly be able to tell from the vibe outside which ones those are). If bars have English menus or seem more inviting with their decor, it’s an indicator that they’re comfortable opening up their doors.

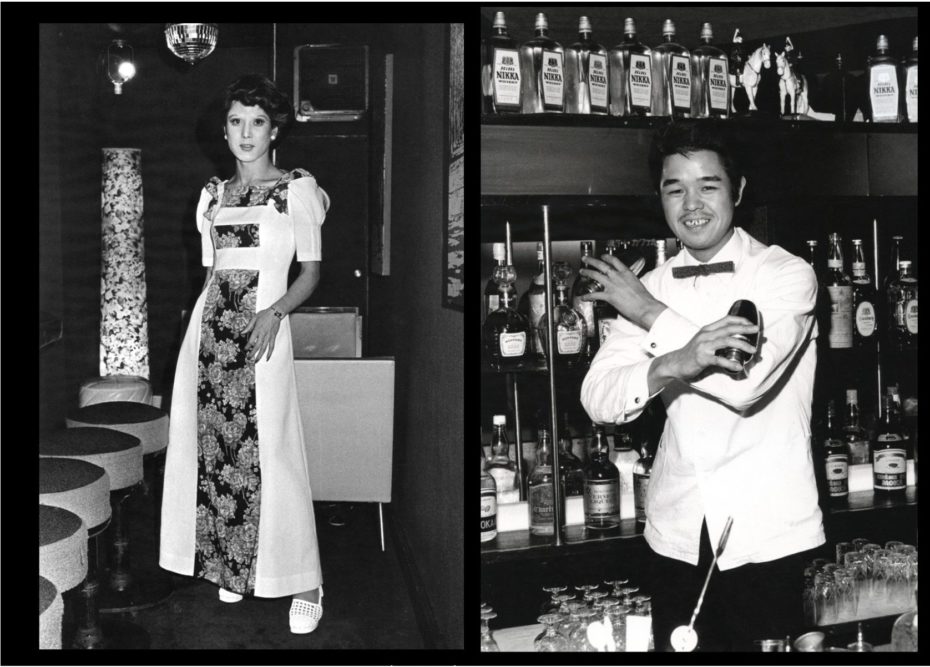

Most of the bars (nomiya) are so tiny, with a maximum of 5 or six seats, that it’s basically just you and the barman, which explains why some are choosy about who they invite in. Make your way through the maze of alleys, up steep and narrow stairwells covered in posters to try your luck with intimate second-floor and back-of-house joints offering a laid-back intimate drinking den or something more surreal.

Venture respectfully into the Golden Gai stretch and follow “the rules”. For example, it’s considered taboo here to linger at a bar, especially when there are people waiting outside. And try not to show up to these tiny bars with an entourage – locals and foreigners alike are rarely as welcome in large groups. Roll two or three deep at the max. Also be careful with taking photographs of anyone without permission.

Some bars also have Golden Gai “taxes”, but it’s always clearly indicated outside whether an establishment has cover charges.

We recommend exploring yourself and bar-hopping (as opposed to outstaying your welcome in one place) to find your favourites, but here’s a few from our short list:

- Bar Kodoji is a welcoming photographer’s bar covered in old snaps of Tokyo. Meet other photographers, local and foreign and browse through photo books over a a cold one

- Kenzo’s for its 1980s vibe with cheetah-print walls

- Bar Darling for its reputation as a very female-friendly bar

- Kohaku if you’re looking for something a little fancier

- Zucca’s if you want a Halloween-theme (because themed bars are a staple here).

- Albatross, a former brothel is one of the larger bars, over two floors plus a small rooftop area, outfitted with taxidermy and chandeliers and some very good whiskey behind the bar.

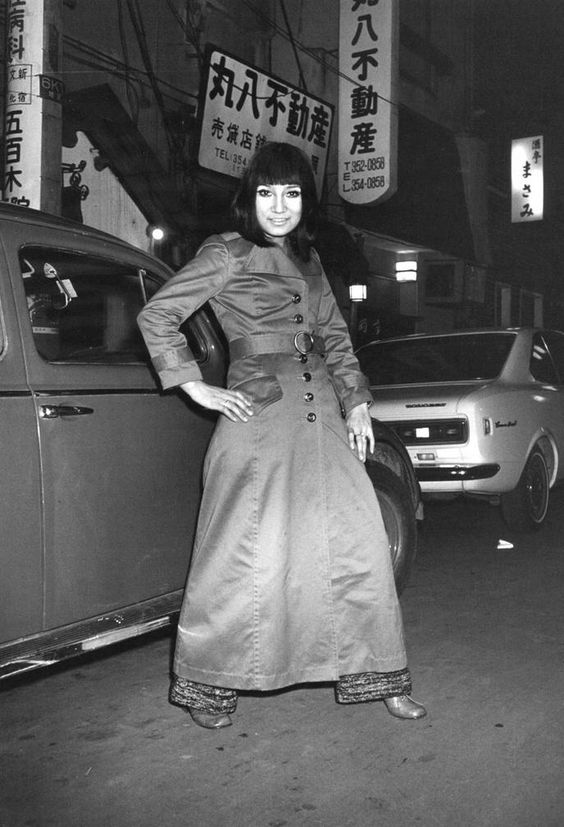

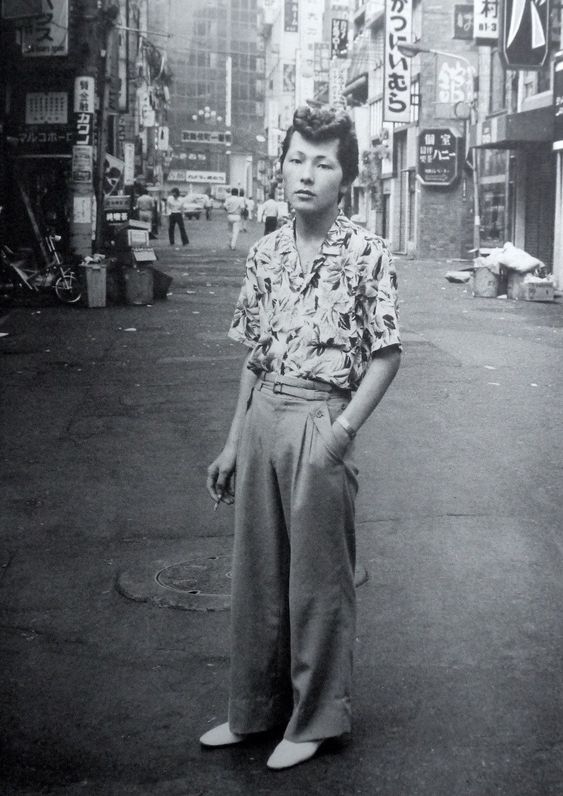

While the Golden Gai is more of an in-the-know drinking spot rather than actual red light district today, the spirit of the tenement-style “speakeasy” is still very much there. These were the backstreets that photographer Watanabe Katsumi frequented circa 1962, fresh from the countryside at 21-years-old.

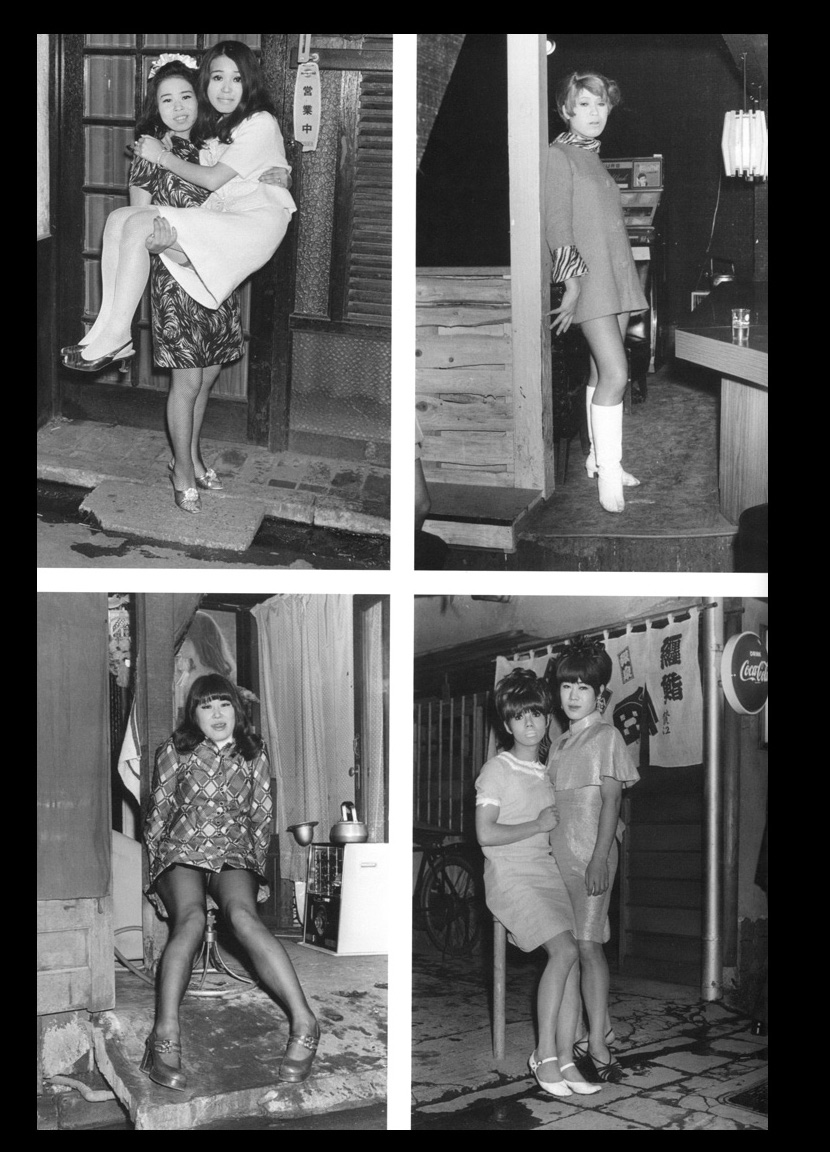

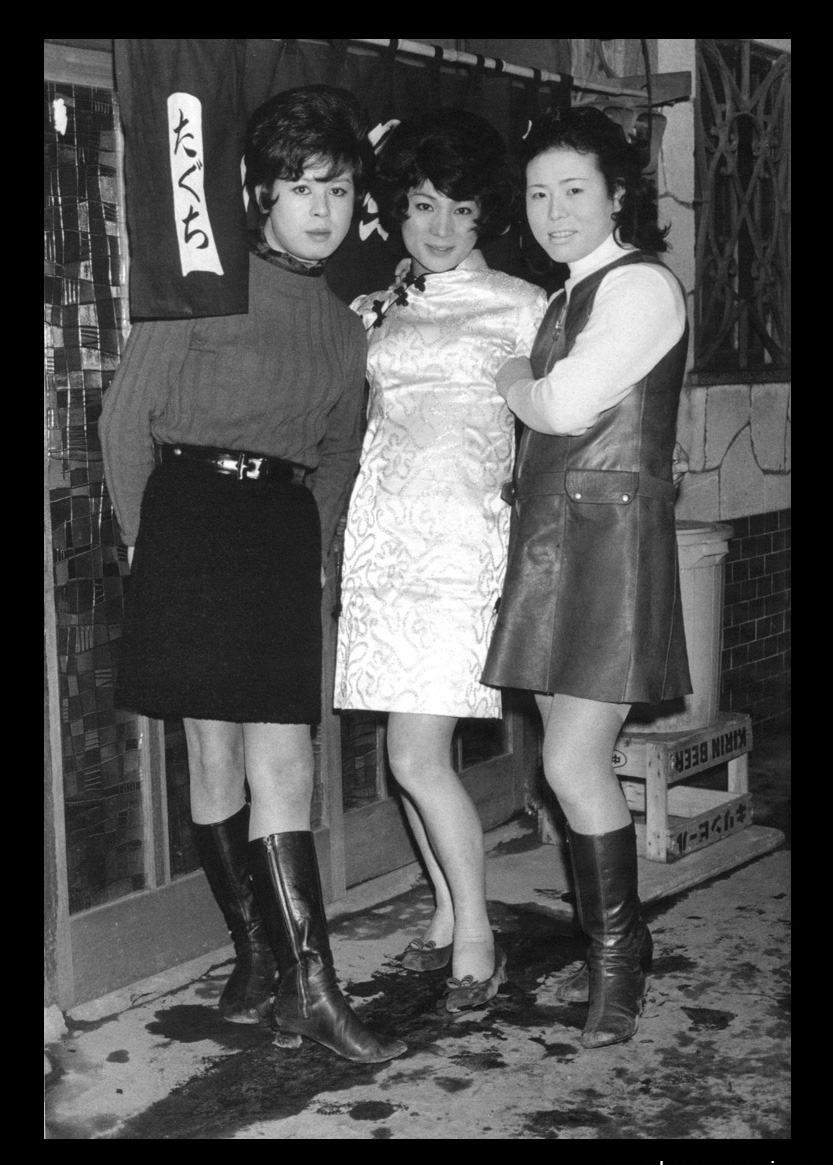

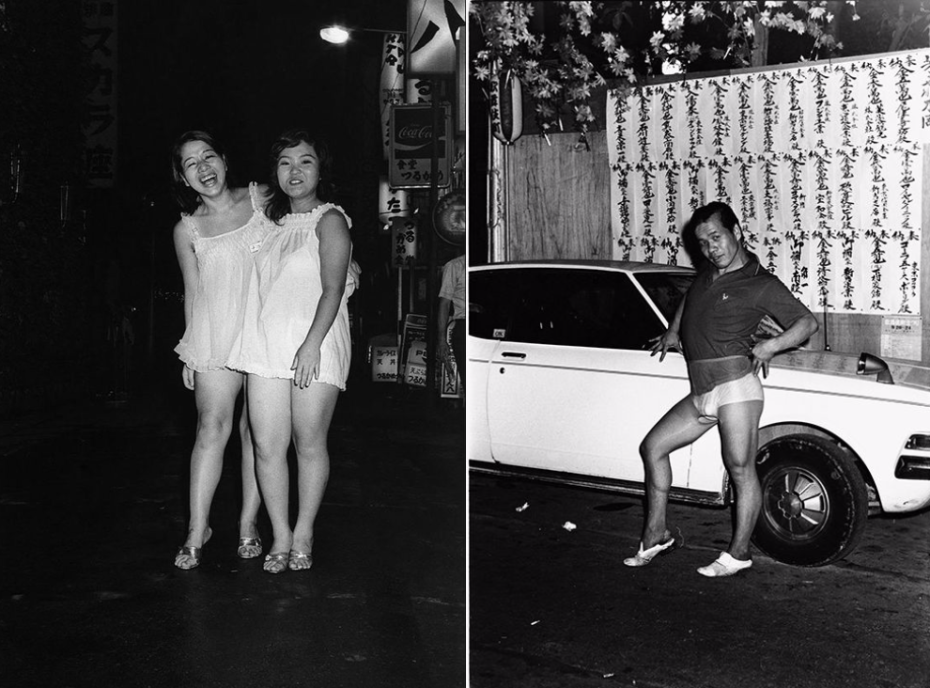

At this point, the girls (and guys) in Kabukicho wear mini skirts, go-go boots, and leather jackets. War is over, and Japan’s collective, creative mentality bubbles over with a groovy weirdness, a newfound taste for expression with a high threshold for vice in the Golden Gai bars…

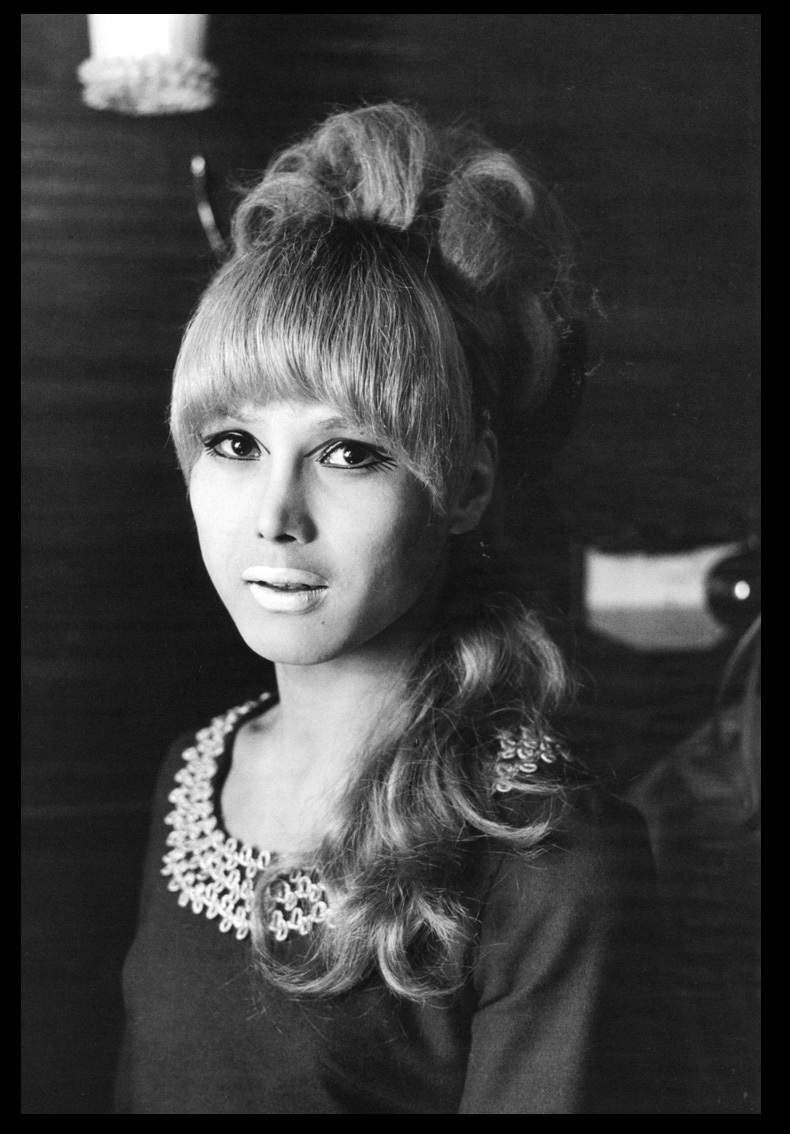

Back then the area was also known as the “blue light district” in lieu of “red”, in reference to its cross-dressing residential sex workers (the former would use blue lights to identify themselves in contrast to the red lights used by others). In the 1950s, Tokyo had its own secret society for the growing cross-dressing community called the Fuki Club which was housed in secret apartments and offered a place for members to store their clothes and accessories away from their families. It was also a safe circle in which less-experienced cross-dressing members could exchange clothes, make-up tips and generally find support amongst each other. (More about this in Queer Japan from the Pacific War to the Internet Age).

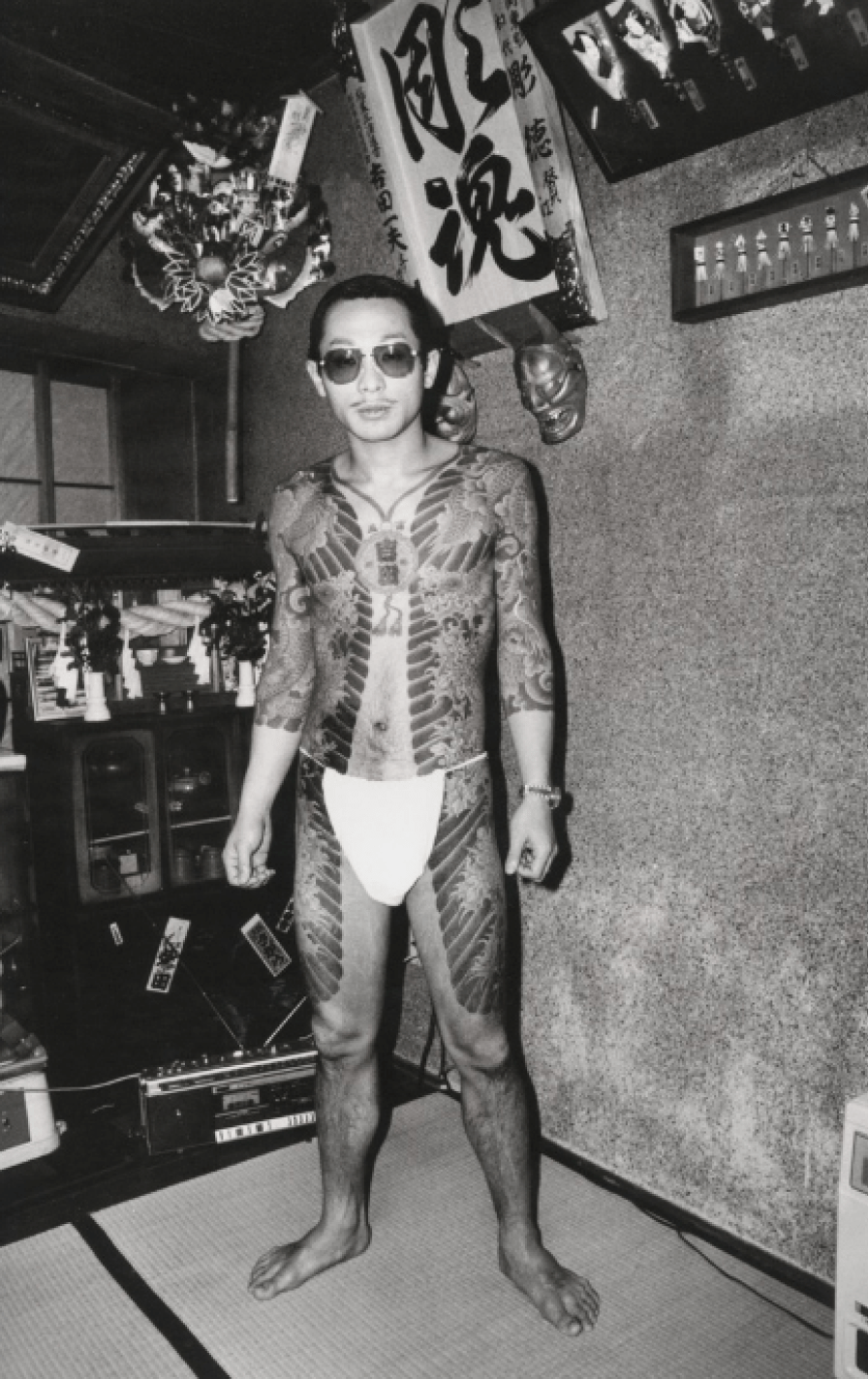

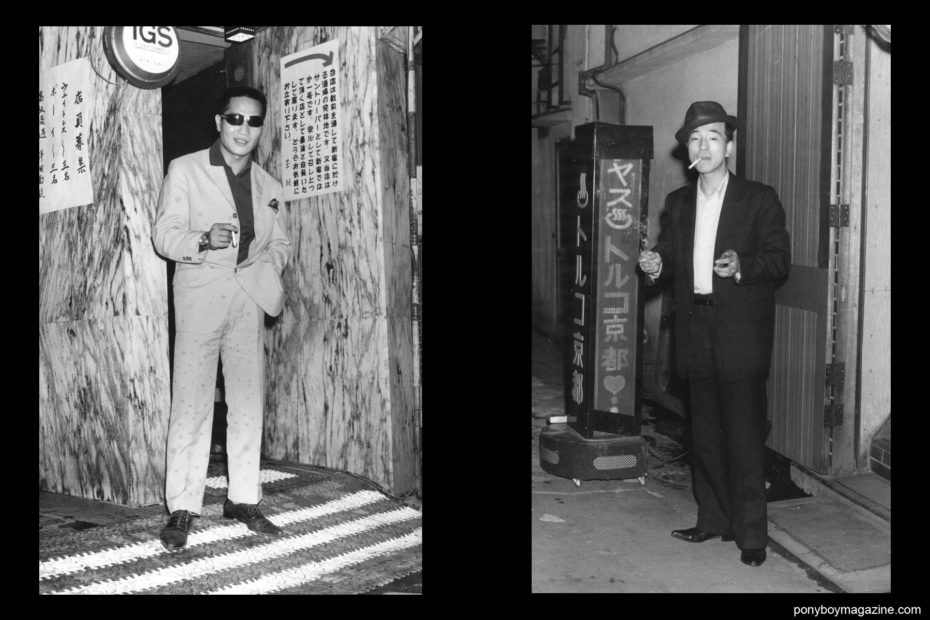

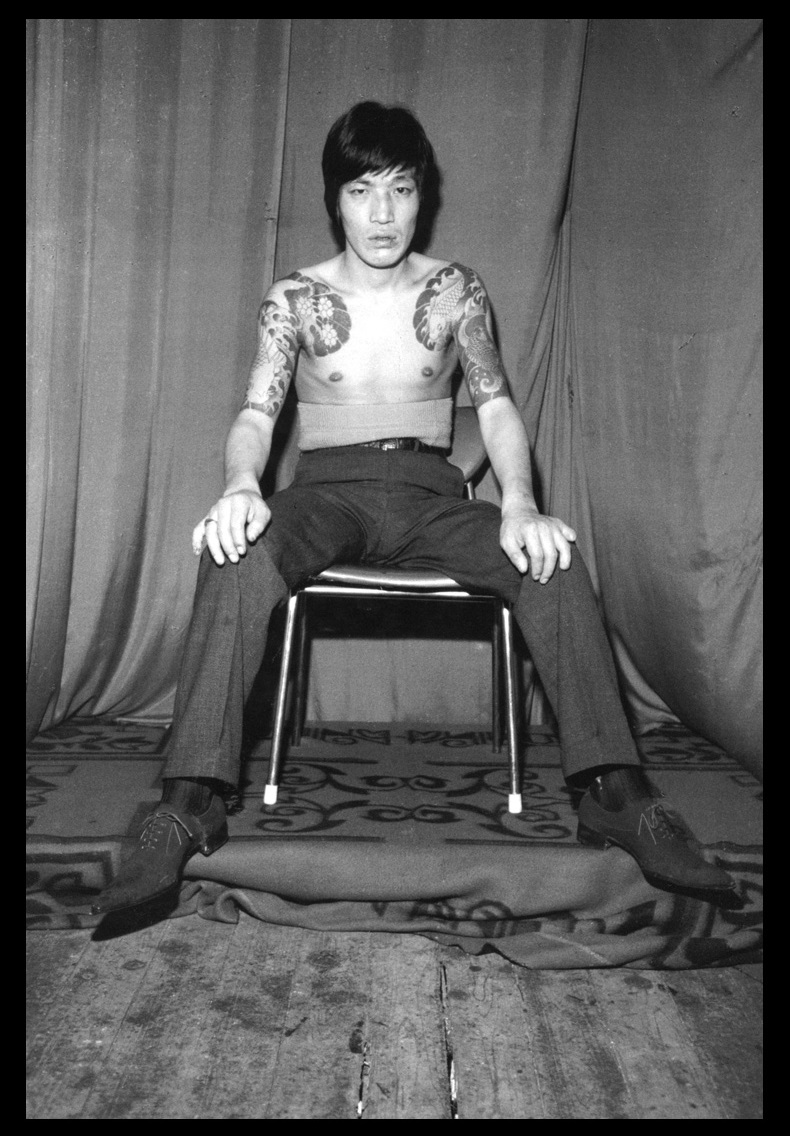

Camera in tow, Watanabe Katsumi somehow managed to take portraits of this blue zone and its residents; the drag queens, bar hostesses, prostitutes and even a Yakuza gangster wearing paper pants – all without getting a supreme arse whooping. The drifting photographer would walk around Shinjuku everyday with his camera and cleverly wait for them to ask him to shoot their portrait. And many of them knew how to ham it for the camera:

Katsumi himself was a very private man, one who covered the tracks of his personal life well. We couldn’t even find an awkward stock photo of his face, despite the fact that his career continued for nearly the rest of his life; his camera captured the bowl cuts of the ’70s, shaved heads of the 1980s, and everything in-between. It was Harajuku before Harajuku, in the grand scheme of street style photography.

We do know that he presented himself as a photographer-for-hire, always returning the following day with processed prints to sell back to his many muses of the previous night for about 200 yen. They were his customers. It was a way to make a buck, certainly, but it was also his way into their world.

We also know he learned the art of photography at Tojo Photo Studio in Tokyo, and was himself a man of many hustles. He shot for weekly Japanese magazines like Focus and Bunharu, but also worked at a bakery.

When he first released a collection of his work in 1973, The Gangs of Kabukicho, he had to self-publish, and he only ever had one solo show in his lifetime (in 1986) despite being selected for the “Fifteen Photographers Today” exhibit at the Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art in ’74. As the years went on, he pumped the breaks on street style photography, preferring to run his own portrait studio and sell roasted sweet potatoes on the sidewalk – all while being able to hold court with, say, the Rockabilly motorcycle gangs that had swept the nation in 1950s (and are still going strong today).

International recognition came mainly after his death in 2006 from galleries like Andrew Roth in New York City, which curated a show on the artist they crowned “a modest gentleman,” and produced a book of his works that sparked an instant dialogue, and nostalgia, for pre-Giuliani New York. Even The New York Times review of the show longed for the days when 42nd street spilled over with not only individuality, but pride in the utterly and wonderfully weird. “Watanabe had a keen sensitivity for the natural posturing of his subjects,” Roth explains online in regards to the photographer’s creative approach, “which allowed them to uninhibitedly reveal their identities.” In making their stories visible, he pulled them out of place of taboo conversation, and into one of celebration. So if you ever find yourself wandering around Japan’s Red Light District, remember: Katsumi captured it when it was still blue.

Learn more about Watanabi Katsumi through the Andrew Roth Gallery, which is now the caretaker of his estate. All archive photos courtesy Andrew Roth Gallery in association with PPP Editions, New York.