Monsters once lived at the heart of pop culture, albeit during what was arguably the weirdest time to be alive: the Middle Ages. In intrepid, faraway lands you’d find them: neckless men with their faces in their stomachs – known as “blemmyae” – or yet another being, known as a “panotti”, with ears big enough to wrap around its body like a blanket. Some feel more relevant today than others (hi, unicorns) and even make appearances in contemporary art and fashion. Others, like the one-footed “sciopodes” haven’t remained at the forefront of our collective western consciousness. At least, on the surface. We’d argue that even the lesser-known medieval monsters hold a formidable mirror up to our current cultural norms and behaviour – that far from being crusty, musty and irrelevant, these fantastic beasts still reveal our deepest prejudices, fears and hopes. So without further ado, let’s unfurl the most jaw-dropping grotesques of yore…

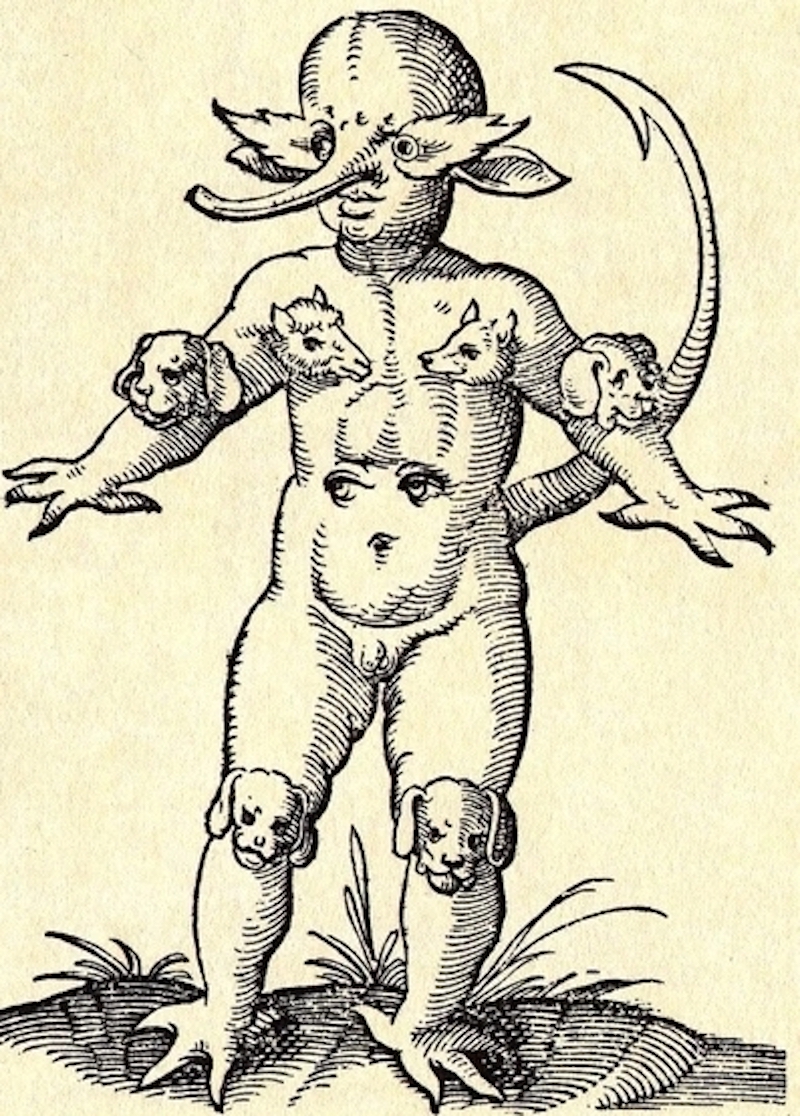

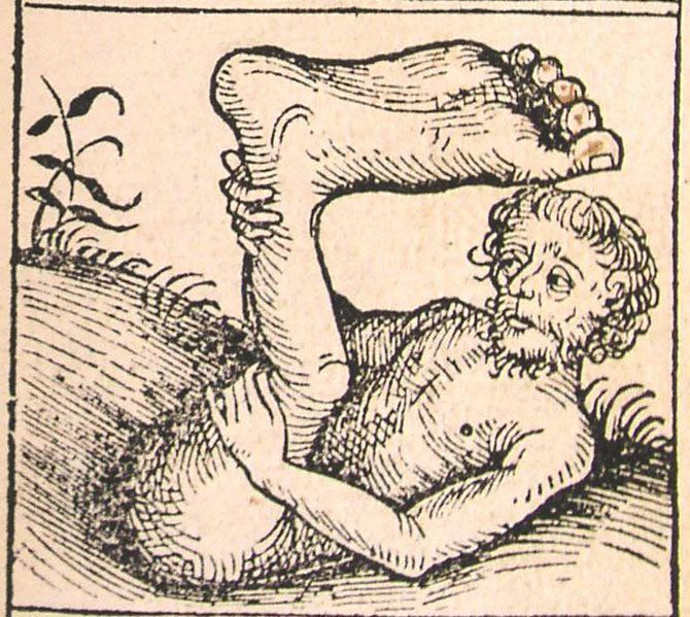

Let’s turn back to the blemmyae legend, which is equally weird and revealing. “Their eyes, nose and mouths protruded from their sternum,” writes historian Jack Hartnell about the fictional race in 2018’s Medieval Bodies: Life, Death and Art in the Middle Ages, a book that’s proven indispensable (and insanely entertaining) for our research on ye olde life. Blemmyae were believed, even as far back as Ancient Roman times, to live in north-eastern Africa. In essence, they were the embodiment of peoples they simply didn’t know, a barbaric face to put on unexplored lands that took on a life of its own.

In fact, old historical accounts claim the Emperor Diocletian enlisted mercenaries to safeguard his empire against raids by Blemmyaes. As time went on, generation after generation embellished this “outsider” monster as they saw fit.

“Throughout the course of history,” writes Hartnell, “layers were added to [their] mythic ethnography” that aren’t improbable on the subject of persons with congenital disabilities. Meaning, folks born with a physiognomy that differed from the societal norm (i.e. an uneven leg, an extra finger) found more and more of a parallel with what was considered strange.

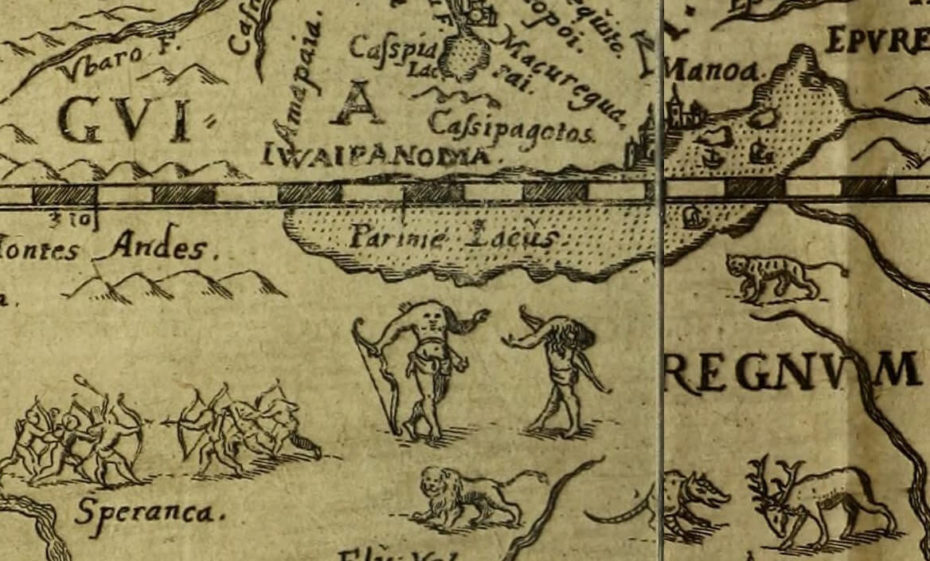

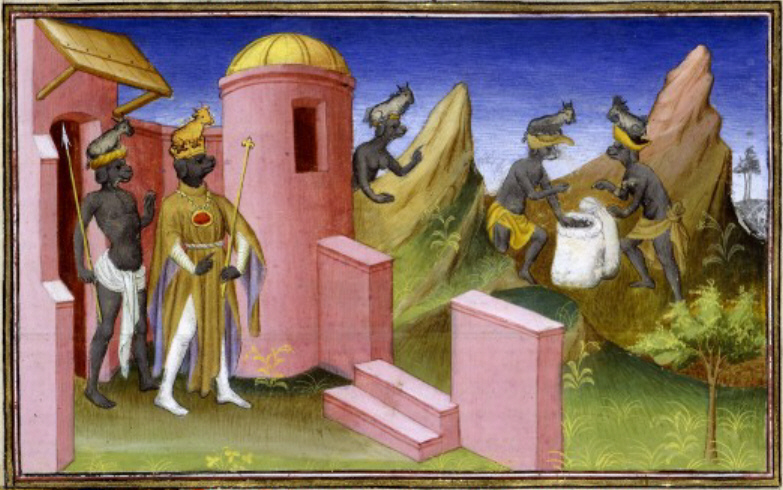

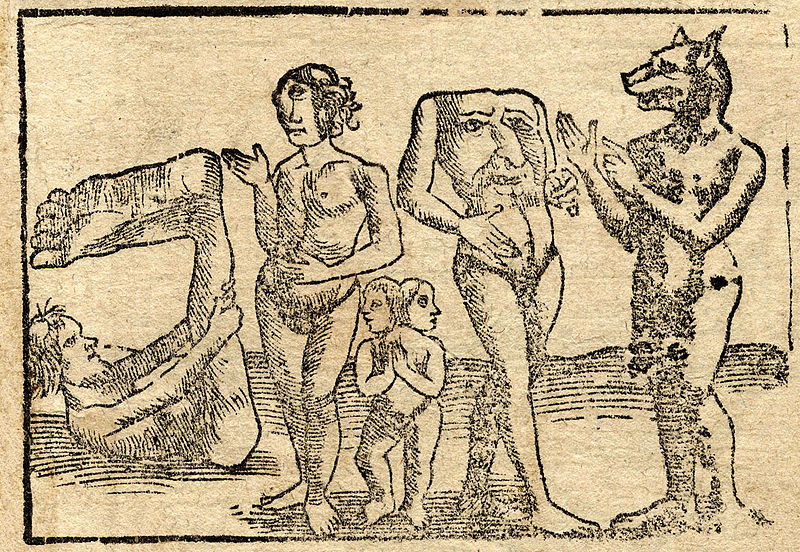

Travellers claimed blemmyae grew eight feet tall and eight feet wide. By the 12th century, they were rumoured to be cannibals who lived amongst other “monstrous fellows” outside of Europe, like the cynophali with their dog heads in India:

And then there were the monopods believed to live in Ethiopia: they wandered the scorching desert, hopping around on one tremendous, trunk-like foot that doubled as a parasol when lying on their backs.

These beings were born out of imagination and ignorance, enduring for so long simply because if history has taught us anything, it’s that humans are disturbingly good at “othering.” Nevermind that the blemmyae monster eventually seemed far-fetched. They were a great foil for Adam and Eve. Exaggerated, often composite physiognomies were a powerful way of showing Christian (and un-Christian) values to an often illiterate public. The head was considered one of the holiest aspects of a human (hence, why humans walk upright as beings closer to God, whereas animals crouch on the ground by Satan). If the blemmyae had their heads in their stomachs, it’s because they weren’t in God’s favour.

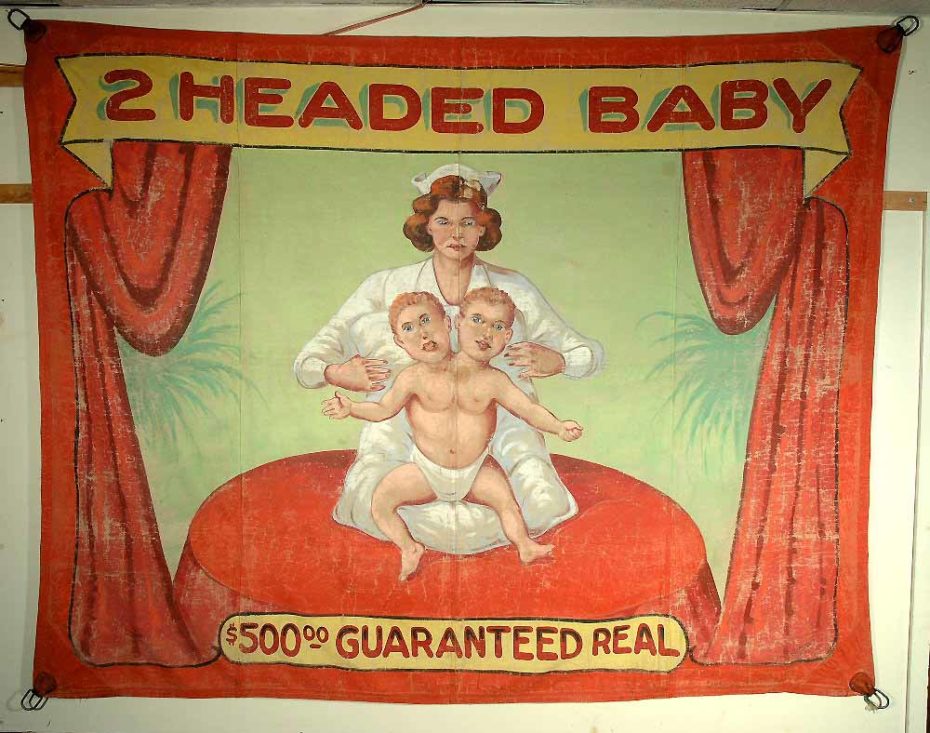

It’s the kind of logic that has persisted into the 20th century regarding not only deformations at birth, engendering the stigma into the Barnum & Bailey “Freak Shows,” but racist anthropology on both academic and mainstream level.

In short, when we trace the hurtful exaggerations we find in caricatures of those who have been historically repressed, and we dig back far enough, we find “monsters” like the blemmyae.

In matters of mythical animals, today’s general public is well acquainted with unicorns, mermaids, griffins, and even basilisks (giant serpents à la Harry Potter and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales). It was all a part of “The Bestiary,” says the Metropolitan Museum of Art on their site, “a collection of descriptions and interpretations of animals, intended as both a natural history and a series of moral and religious lessons [that] was widely read in the Middle Ages.”

Bestiary creatures like the manticore, for example, were a lesson against sensual temptation: it had the body of a lion, face of a human, and a scorpion stinger, but a voice so sweet and “flute-like” it lured people to their death (like mermaids).

Other creatures in the Bestiary proved less overtly monstrous. The crocotta, for example, was a mythical, dog-wolf-lion hailing from India or Africa. The bonnacon was a beast from Asia that basically looked like a ram or bull, but with deathly powerful, backwards horns, and the Ethiopian anabula was a wonky elephant with hooves:

Exotic animals did make their way into the courts of various kings and high-ranking figures, which is why their depictions weren’t solely left to conjecture. And to let you in on a bit of ye olde gossip? Apparently the 16th century Pope Leo had a pet white elephant named Hanno he loved more than life itself. He even buried him in the Vatican when, after only 2-years in his care, he died from a gold-enriched laxative. But we digress.

The fact of the matter was, even the most seemingly banal of animals could be attached to some pretty crazy mythology. We asked our favourite Insta-famous medieval specialist at Discarding Images (@discardingimages) for their favourite ye olde monster expecting an obscure beast. Boy, were we wrong. “A beaver,” they wrote, “Why? According to the bestiaries it castrates itself (check the iconography). It literally (in a legend) bites its balls off. Impressive, isn’t it?” That’s one word for it.

We’d never heard of the beaver balls legend, but the myth that oysters are an aphrodisiac is the perfect example of a medieval belief that’s thriving in our day and age (the 16th century French physician Laurent Joubert claimed they were a laxative that could also encourage sexual desire); Again, on the other end of the spectrum the belief that brussel sprouts were filled with tiny demons and had to be cooked after cutting their stems with an X shape, has died out.

As English folklore aficionado Scott Walker explained to us, “Many of our western culture’s common superstitions were born in the Middle Ages. Prior to the rise of medieval Christianity, black cats were actually good luck for Pagans,” and that they remain so today is a reflection of Christianity’s staying power. Black cats aren’t monsters on the blemmyae level, certainly, but in a way they’re just as fascinating: they show how very normalised some ye olde supernatural creatures have become.

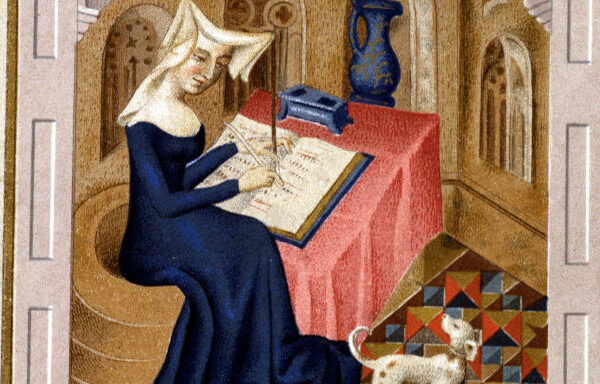

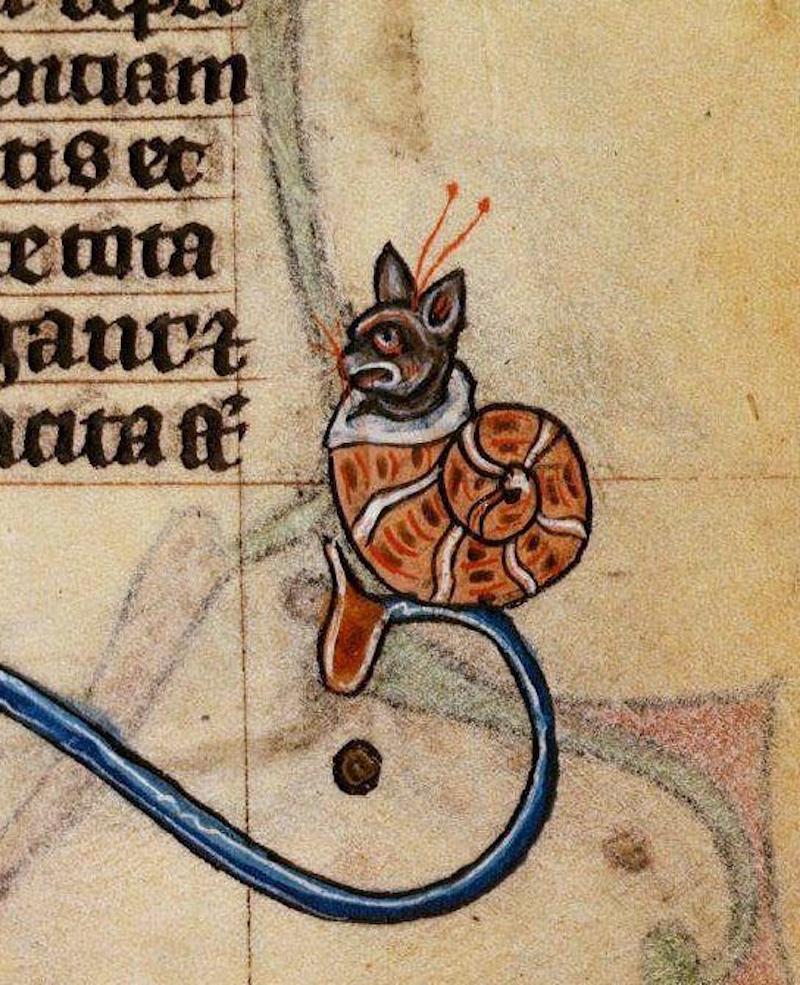

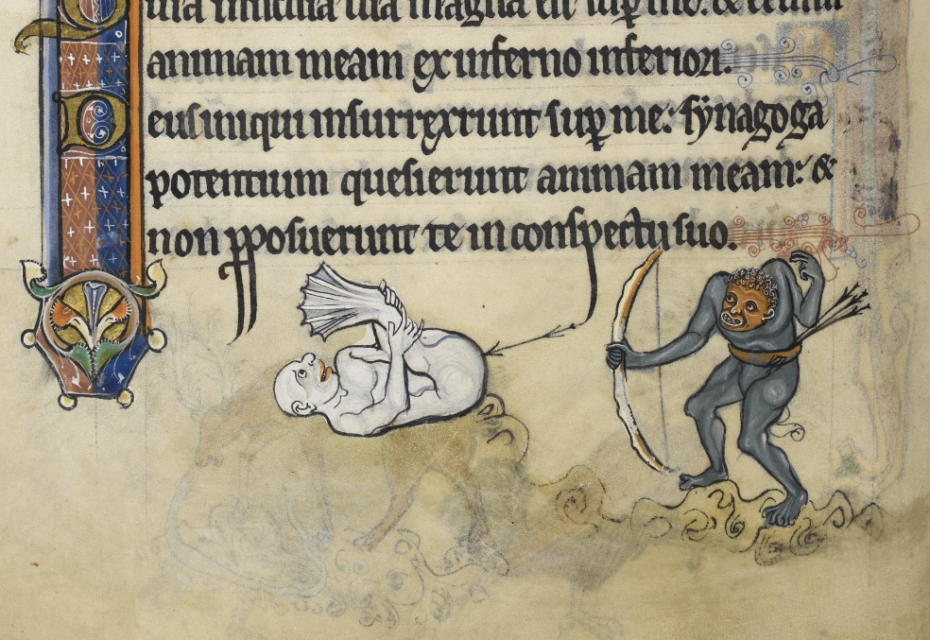

To underline the normalisation, and pervasiveness of these bygone monsters, it may help to mention that they even lived in the margins of manuscripts as doodles akin to what you would’ve drawn on a notebook while day-dreaming in primary school. Only, instead of scribbling the Spice Girls and hearts, they scribbled rabbits riding lions, and other composite beasts. Some were more complex than others, and even aimed to draw attention to important parts of a text, while others were less sophisticated:

These monsters are still everywhere for those curious enough to probe the weirdest old wives tales with a sharp eye. They’re on the shelves of toy stores, and in Game of Thrones; in Halloween movies, and even walking down the runway for Gucci during Fashion Week:

Also: shoutout to the ye olde Yoda sandwiched in between the text below:

They’re even popping up in contemporary art galleries. Los Angeles-based Artist Roberto Benvidez just turned these little medieval buggers into the most gorgeous, painstakingly detailed piñatas:

Why? “The manuscript creatures echoed that same medieval style and oddness that inspires my own work,” he told MessyNessy, “I am drawn to creatures that are either fantastical, unidentifiable or a mashup of different animals.” His 2018 series is based on the illuminated texts like The luttrell psalter (c. 1325-1335), the medieval bestiary (c. 1210-1220) and the book of hours (1410), and brings the monsters to life in the most beautiful, and startling way through the much more relatable, contemporary context of a piñata.

“I believe art from any time period should have the opportunity to be appreciated by the current population,” says Robertro, “I look to these monsters more for their artistic nature (form, color) and less the context of the time (although that is interesting to me, too).”

“These piñatas can be seen as a sculptural treatment of a cultural object that expresses appreciation and places value on something that is otherwise viewed as cheap and disposable,” he says, “which also connects to underlying racial issues. These pieces play with cultural hybridity.”

The colour, the whimsy, the weirdness – it’s easy to see why the we continue to come back to these creatures of yore. Some of them, like the blemmyae and other human “monsters,” reveal the seeds of discrimination, but so many others open up our imagination, and, in Roberto’s case, creative ways of fighting the discrimination they engendered over time.

Our curator over at Discarding Images agrees. “Monsters from our point of view are beings from another world,” he says, “[and] at the same time we can trace their origins in antique writings, scientific and spiritual treatises. Medieval art was in constant movement and constant use. It was truly alive.”

Learn more about Roberto Benavidez’s work here, and find Jack Hartnell’s book on the Middle Ages on his website.