What happens when a samurai puts down his sword, and picks up a paintbrush? In 1868, feudal Japan was steamrolled by a new decade known as the Meiji Restoration. Western influences flooded every crevice of the country’s social fabric, but arguably the most fascinating battle between “old” and “new” Japan took place on canvas. Suddenly, Japanese artists were looking to Europe for inspiration, and they stumbled into the sun-drunk, dappled light of Renoir’s barge party scenes; Degas got them dancing, and Monet’s water lilies proved that you don’t have to paint something accurately to paint it truthfully. Against all better judgement, the “Yōga movement” (“Western-style painting”) blossomed in Japan, eternalising one of history’s biggest transitions in otherwise picturesque scenes. Today, they invite us not to read between the lines, and brushstrokes, of history to understand it…

There’s a 17th century map of Edo Castle, the seat of “shogunate” or military Japan, that seems to sum up everything pre-Meiji quite well. It looks a bit like Minecraft, because it kind of was; this moat-guarded labyrinth functioned on a highly structured social system with one overarching goal: to make sure Japan stood strong against colonialist forces…

It did that pretty well until United States commodore Matthew C. Perry came along, rolling up in a fleet of heavily armed ships to “suggest” they open up to trade with the west. Thus, railroad tracks went down, telegraph lines went up, and classist conventions were being chipped away under the motto of Bunmei kaika, “Civilization and Enlightenment.” Creatives, too, were encouraged to learn new languages, crafts, etc. from the West.

Enter Takahashi Yuichi, the father of the Yōga movement who actually came from the samurai class. On the one hand, there was no one more “Japanese” than Yuichi, who painted court members – even the emperor – and a simple picture of a dangling salmon that’s gone down as a national treasure. On the other, Yuichi was mostly self-taught. He learned some tricks from a British mentor, but when he’d mastered the art of the oil paint still-life swapped the whole grapes-and-chalice thing for some crispy tofu:

But just as Yōga found its footing, so too did a movement dedicated to upholding traditional Japanese art: “Nihonga” painters. They didn’t use oil paints like Europeans, nor did they aim to create the same visual depth and perspective of, say, a really juicy Rubens on their subjects. The beauty of their work was in precision, and simplicity, whereas the impressionist’s canvas arguably worked on a “more is more” mentality. Needless to say, they scratched their heads at the complete and utter chaos of Monet’s landscapes. “Real” Japanese painting, said those faithful to the traditional ways, was done on washi (silk paper) with ink, containing usually no more than a handful of colours, and with no perspective. (Ok, maybe a bit of gold leaf if you were feeling fancy)…

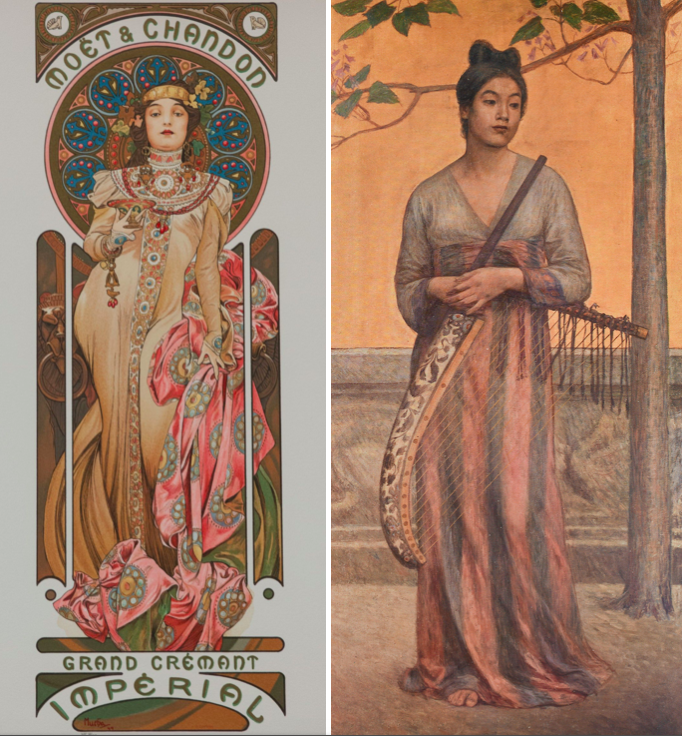

Some of the most stunning art from this period was also the kind that didn’t quite know if it was Yōga or Nihonga; the kind that looked like a new kind of Monet, or even had one foot in Art Nouveau or Deco as the years went on. Yōga was born in tandem with movements barely in its rearview mirror, which meant there was room for just about any Western aesthetic…

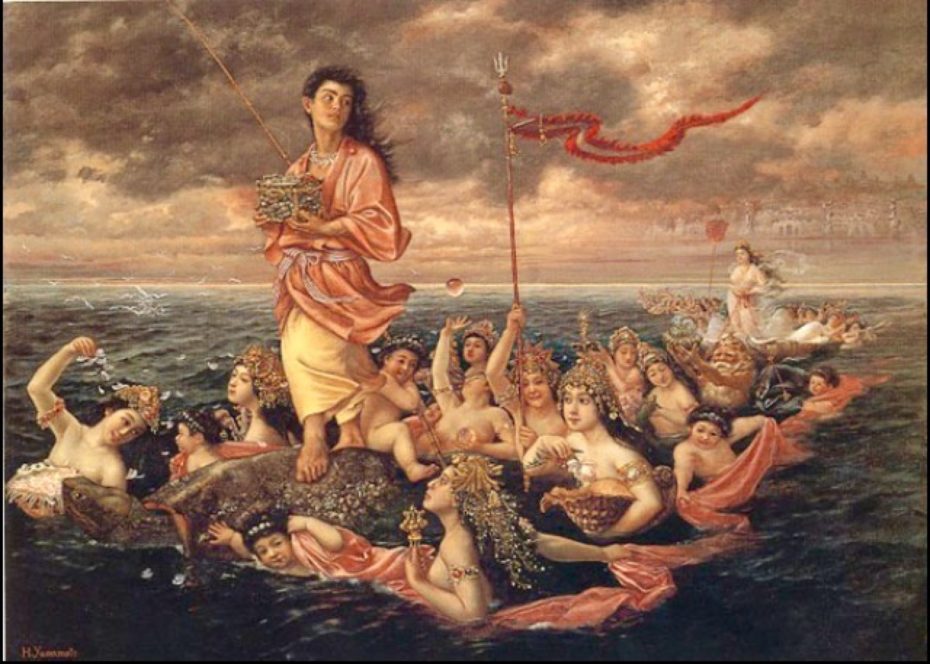

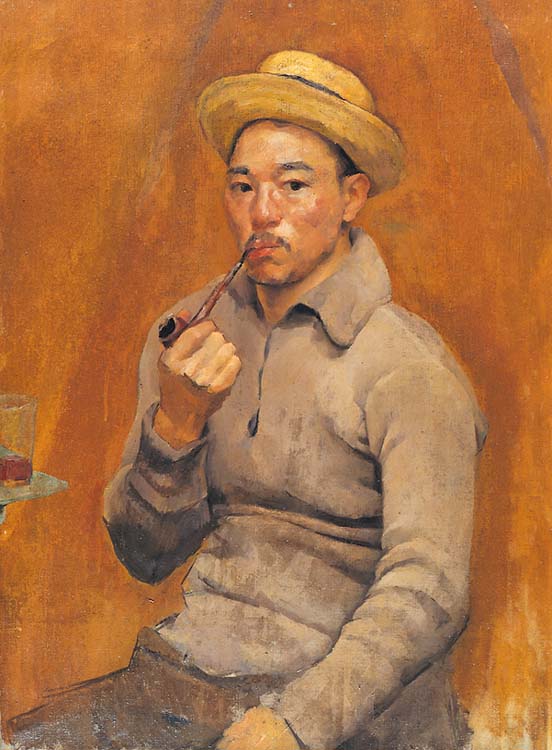

In 1889, Yiuchu founded “Meiji Bijutsukai”, the first official group of Western-style painting in Japan. Artists like Asai Chū, also of the ex-samurai class, gave Monet’s haystacks a run for their money; Shigeru Aoki and Yamamoto Hōsui often wove Japanese myths into their flamboyant brushtrokes, with Hōsui even going on to illustrate works for the French dandy Robert de Montesquiou. They were all works that could’ve blended in seamlessly at any French salon, despite the fact that a good number of the brains behind them had never left Japan.

The king of the crop, however, was undoubtedly Kuroda Seiki, who came from upper-crust samurai stock, and spent a decade in Paris painting en plein air, working in a big artist’s colony, and generally being one step ahead of the curve; he painted mandolins before they’d ever arrived in Japan, and his 1893 painting, “Morning Toilette,” was the first nude painting to ever be exhibited in the country (tragically, destroyed in WWII).

He also started pushing for an avant-garde offshoot of Yoga called “The Hakubakai”, or “The Wind and Light Club” (the name of a popular sake), that wanted to be completely free from what he saw as confining rules within the official Meiji Bijutsukai group.

Impressionism runs through France’s veins with as much fervour as vin rouge, but it’s important to remind ourselves that it wasn’t just adopted by Japanese painters: it was transformed. It also became a small, glittering window into the ways in which art can tighten – or toy with – the way we relate to our national identity.

Here’s the tragedy – so many of these Japanese impressionist paintings were lost during the devastation of World War II; in the firebombing of Tokyo and of course, the atomic bombs that led to Japan’s surrender; that few are known outside of Japan. Most of them have been recovered in estate sales in Japan, but discovering Yōga paintings from this forgotten movement could be a real find…

Like Kuroda Seiki, many Japanese artists were trained in Paris to learn the latest Avant Garde European styles. Kanae Yamamoto was another Japanese artist, known for his Western-style paintings, who studied at the École des Beaux-Arts on Paris’ Left Bank. Yamamoto is also credited with originating the sōsaku-hanga (“creative prints”) movement:

His most famous print, “Fisherman” (1904), one might say has an air of Van Gogh to it, even though he claimed to dislike the Dutch post-impressionist painter. His financial situation was difficult in Europe and like all struggling artists, selling his work to unknown buyers would have been a quick solution in desperate times. The number of Kanae’s prints circulating to this day is unknown.

The works of Japanese impressionists and post-impressionists might be incredibly rare, but the movement is also so little-known, have we really looked hard enough?

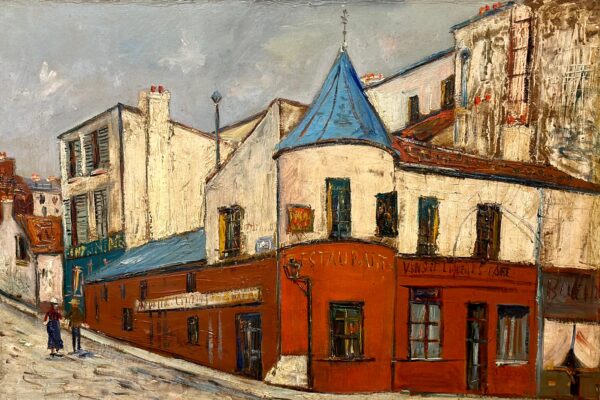

As time wore on, artists like Foujita – who was truly divided between France and Japan – would take the torch from artists like Seiki from the 1900s onward, while the arrival of WWII prompted even the most extroverted of the Yōga school to turn shift their gaze away from Europe, and paint scenes not reminiscent of dandelions by the Seine, but of Japanese military victories. Kind of funny, considering the movement was born in the dissolution of the militaristic government. Perhaps it just goes to show that regardless of where art is born, it’s where it goes that’s telling.